Corporations Lead the Way to American Energy Independence

In 2005, when I was providing seed capital to emerging hedge funds at JPMorgan, we met with Alerian’s founder Gabriel Hammond. “Gabe” knew a great deal about Master Limited Partnerships, and he was convinced that the sector needed an index in order to grow. He was right, and Alerian’s index became the most widely used benchmark for MLPs. We seeded Alerian Capital Management’s offshore hedge fund.

Back then, MLPs were synonymous with energy infrastructure. To invest in one was to invest in the other. But as regular readers know, much has changed since then. MLPs are now a shrinking subset of energy infrastructure. The Shale Revolution created the need for growth capital to build new pipelines, because crude oil hadn’t previously been sourced in North Dakota, nor natural gas in Pennsylvania. The MLP’s promise to pay investors 90% of Distributable Cash Flow (DCF) came into conflict with their desire to invest in new projects. The older, wealthy Americans who owned MLPs were there for the regular income. Foregoing some of today’s distributions in exchange for the promise of higher future returns wasn’t appealing, and MLPs turned out to be a poor source of growth capital. MLPs began “simplifying”, in many cases becoming regular corporations where payout ratios are far less than 90% and investors are global. In short, the older, wealthy American turned out to be the wrong type of investor for midstream energy infrastructure’s response to the Shale Revolution. MLPs were no longer equivalent to energy infrastructure.

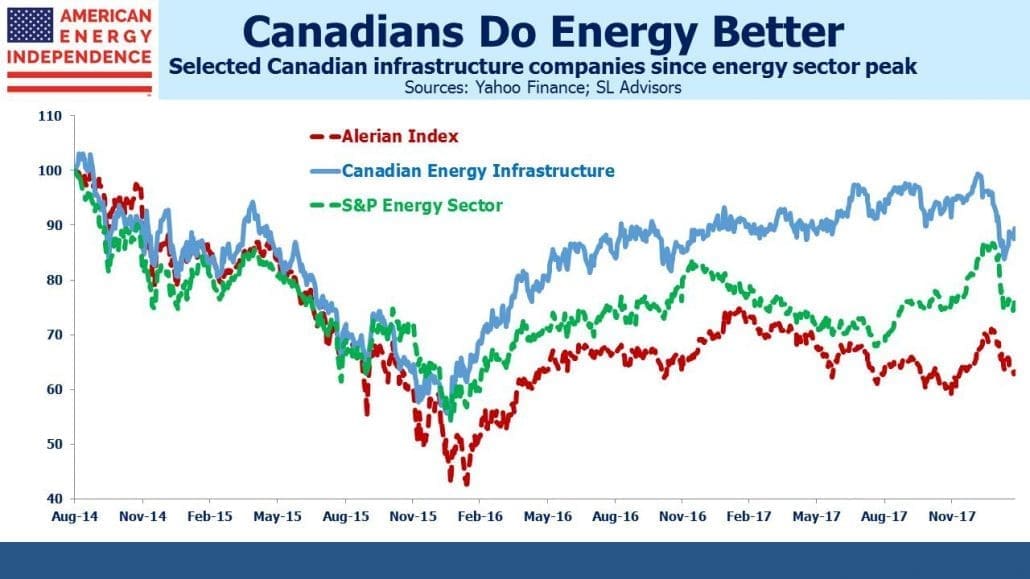

We’ve watched and participated in this evolution as investors. It’s an ongoing source of considerable frustration to many that the energy sector has performed so poorly when the fundamentals appear so promising. The price of oil peaked along with sentiment in 2014, since when the S&P Energy ETF (XLE) has dropped 18% while the broader S&P500 is up 52%. Volumes continue to grow, with crude oil, natural gas and its related liquids (such as ethane and propane) all reaching new records this year.

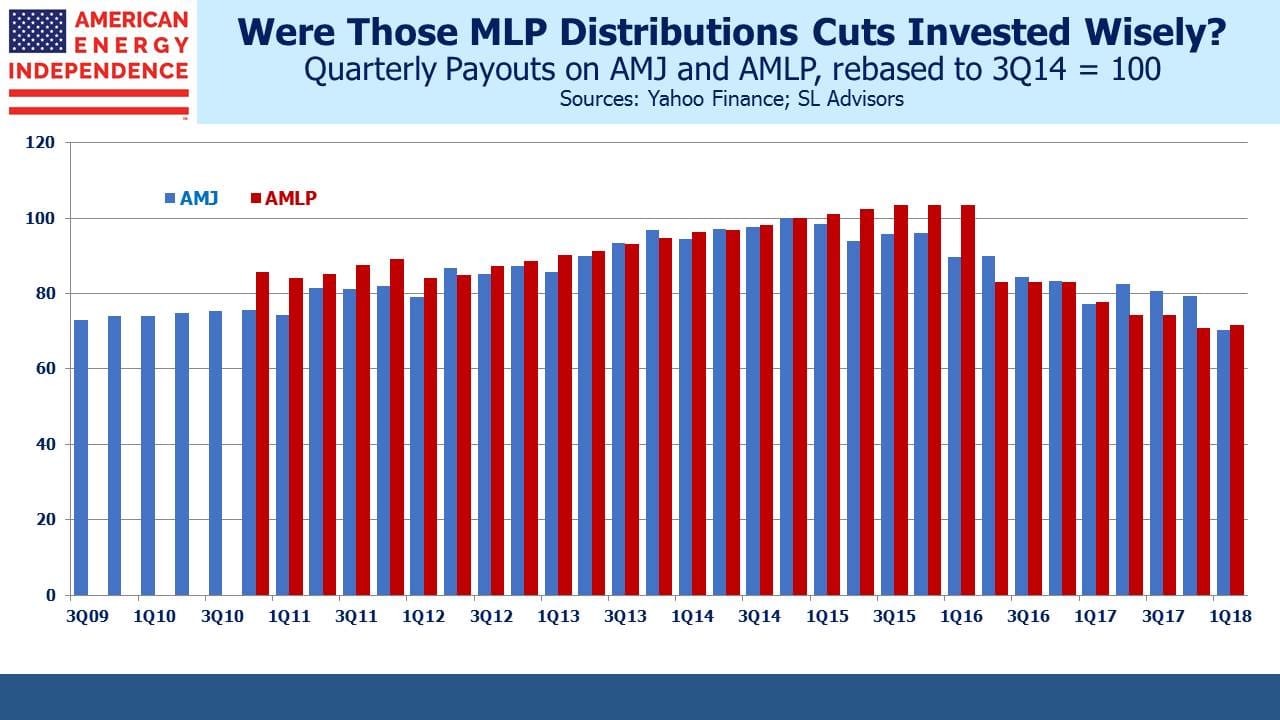

The higher volumes will ultimately drive higher profits for the midstream infrastructure businesses that gather, process, transport and store them, although the alignment of production and stock returns is becoming an interminable wait. In the meantime, the vast majority of funds that specialize in energy infrastructure are dedicated MLP funds. They face a tax drag (see AMLP’s Tax Bondage), and a shrinking pool of names (see The Alerian Problem).

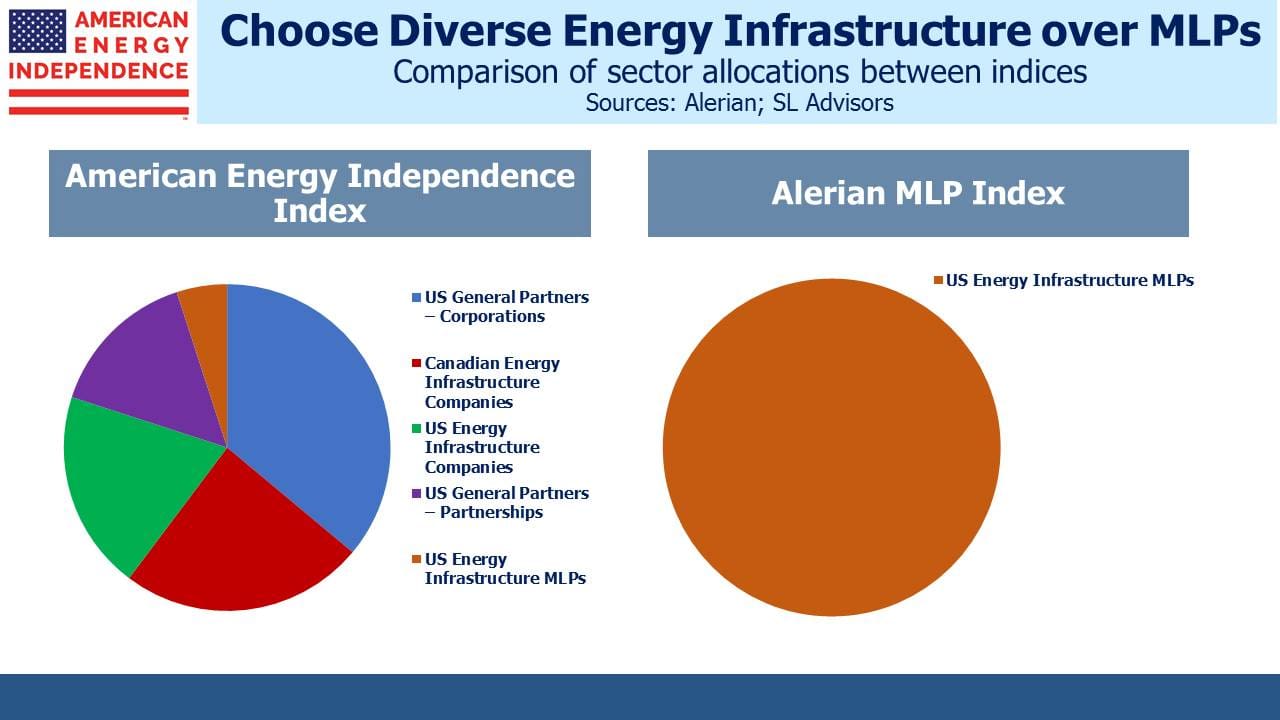

Corporations, not MLPs, control U.S. energy infrastructure. And yet, some of the biggest operators such Kinder Morgan (KMI, market cap $34BN), Oneok Inc (OKE, market cap $24BN), Williams Companies (WMB, market cap $21BN) or Cheniere Inc (LNG, market cap $13BN) don’t appear in the MLP-dedicated funds that, as a result, no longer represent a broad investment in energy infrastructure.

The American Energy Independence Index (AEITR) constituents have a market cap of more than twice that of the Alerian Index. The AEITR also includes General Partners (GPs), whose control of many MLPs provides them with preferential rights as well as being the investment of choice for most management teams (see MLPs and Hedge Funds Are More Alike Than You Think). The AEITR includes some Canadian names, since North America’s pipeline network crosses the border in numerous places and some significant elements of U.S. infrastructure are connected to their northern neighbor’s network.

The result is a far more complete representation of midstream infrastructure. The American Energy Independence Index represents the future, which increasingly is corporate ownership of assets, versus the outdated model limited to MLP ownership. For investors seeking to follow the Shale Revolution’s drive towards American Energy Independence, we believe it offers a superior way to participate.

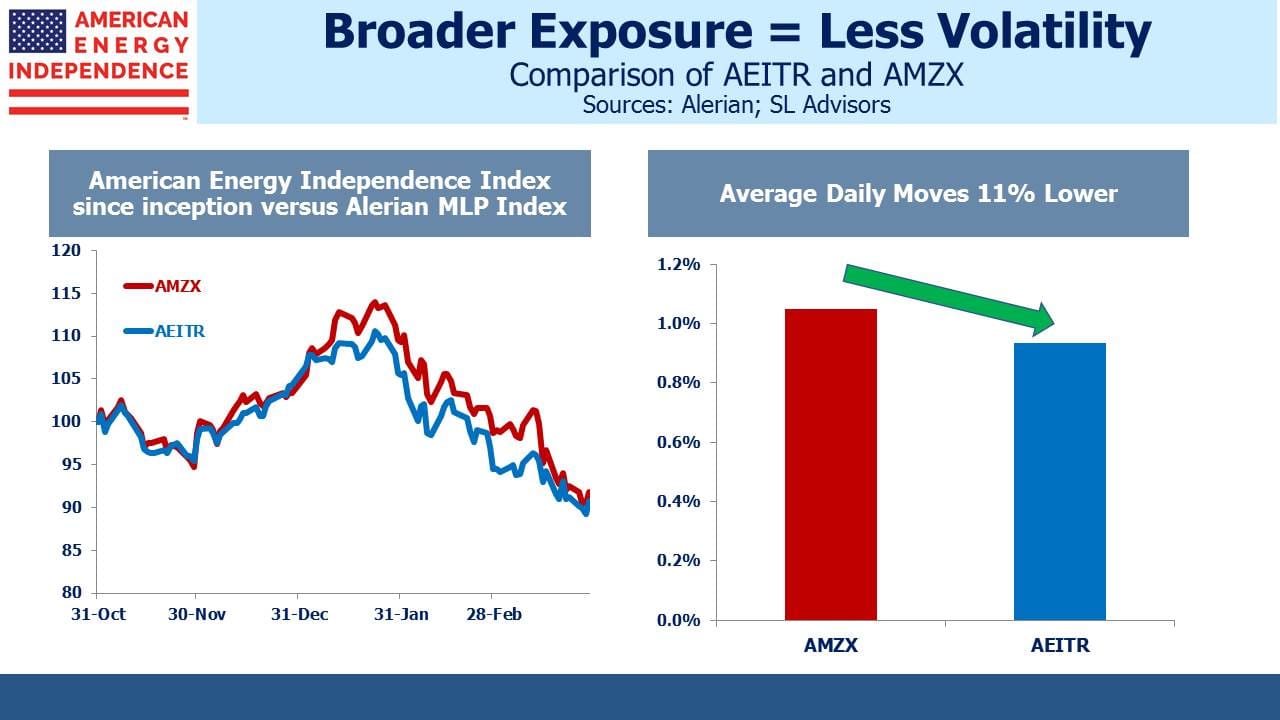

We launched the index in November, and its associated ETF in December. We think because AEITR is more diversified, it has demonstrated 11% smaller average daily moves than the Alerian Index. Given Alerian’s shrinking pool of eligible MLP names and more concentrated sector exposure, we expect the American Energy Independence Index to continue exhibiting lower volatility.