Why Energy Transfer Cut Their Distribution

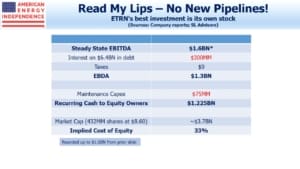

Energy Transfer’s (ET) 50% distribution cut announced late on Monday surprised most observers. Given the comfortable 1.4-1.5X DCF coverage this year and next, many felt that there was little pressure to reduce it. However, the persistently high yield (18% before the announcement), reflected widespread investor skepticism around its sustainability. Debt:EBITDA of 5X is higher than the prevailing 4-4.5X standard for investment grade names in the sector.

The company’s press release provided no additional color, and the 3Q20 earnings call will be next Wednesday, when election results will dominate the news.

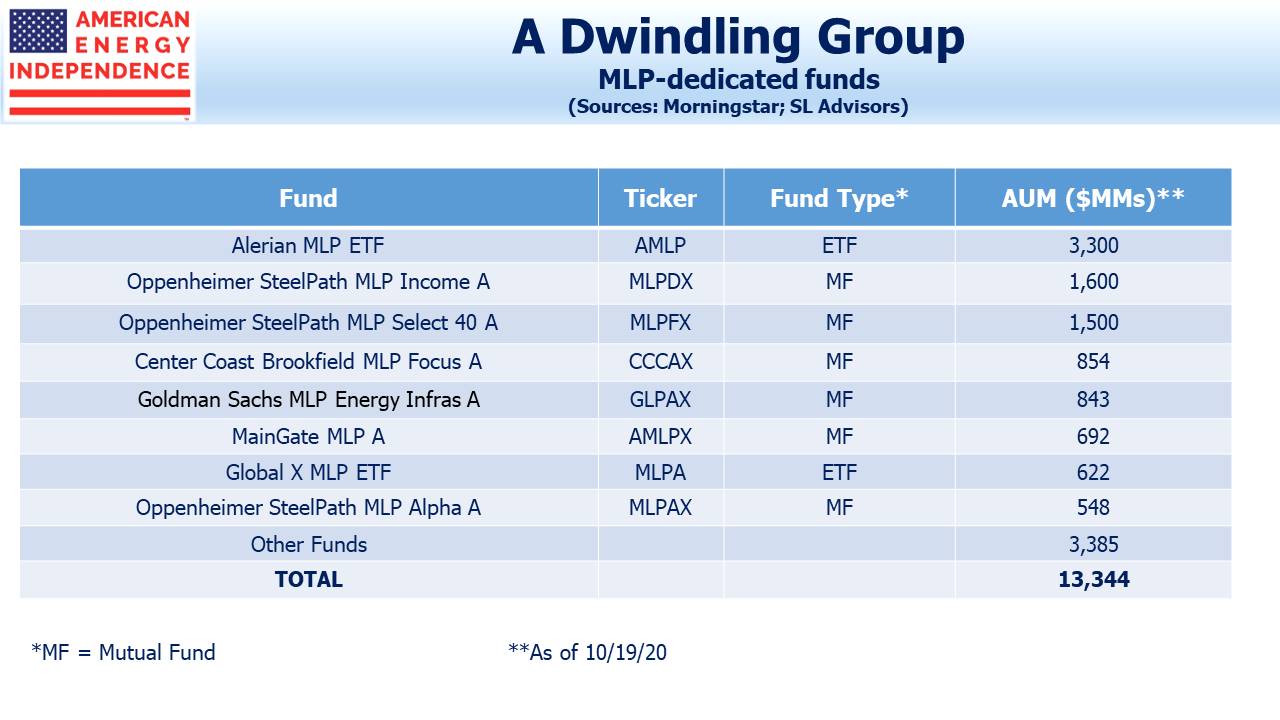

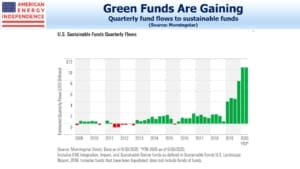

Distribution cuts are rarely well received. Income-seeking investors who used to be the core investor base for pipelines have endured them for years. Few could be shocked by one more. The payout on the Alerian MLP ETF (AMLP) is 50% below its peak of February 2016. Since ET is a 10.1% position in its index, the Alerian MLP Infrastructure Index (AMZI), AMLP is likely to cut a little more. MLP-dedicated funds run by Invesco are also significant ET holders, highlighting the problems such funds face with a shrinking pool of investable names (see Why MLP Fund Investors Should Care When They Change).

Selling on Tuesday following the announcement likely reflected disappointment from investors who had believed the DCF coverage meant it was secure.

The problem was that too few investors believed the distribution would be maintained, and this became a self-fulfilling prophecy. The high yield meant it was a waste of money to keep paying it. The stock is too cheap to be used as an acquisition currency. Retiring CEO Kelcy Warren’s substantial income from the distribution was one of the arguments for its continuation, but he can probably get by on less.

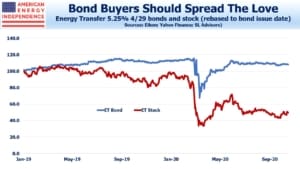

A few weeks ago we contrasted the negative view of ET held by equity investors with the relative equanimity shown by their bond yields (see The Divergent Views About Energy Transfer). As the chart shows, strong differences of opinion about ET persist across the capital markets. A ten year bond issued by ET in January last year trades above par, after falling sharply earlier this year. By contrast, ET’s stock price remains at just half the level it was when the bonds were issued.

This is a theme with investment grade pipeline stocks. Enterprise Products Partners (EPD) is another example of a company whose bonds reflect a much more positive outlook than does their stock (see Stocks Are Still A Better Bet Than Bonds).

Pipeline stocks have long abandoned any connection with Miller-Modigliani and the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). Theoretically, investors should be indifferent to leverage or dividends for example, but in practice they are not. Once the reactive selling from those who liked the former 18% yield is finished, investors will see a company with more financial flexibility. They could use some of the cash freed up by the distribution cut to repay debt, although their bonds are expensive. Or they could initiate a stock buyback, directly confronting their low valuation.

We’ll need to wait until next Wednesday to learn more. ET has often been criticized for exploiting its investors where possible. The convertible preferreds they issued to management in 2016 following the ill-fated pursuit of Williams Companies (WMB) permanently cost them trust in the marketplace, and is a reason for their continued depressed stock price (see Energy Transfer’s Weak Governance Costs Them). Newly promoted co-CEOs Mackie McCrea and Tom Long have an opportunity to demonstrate good faith with investors.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.