Strengthening Your Portfolio With Pipelines

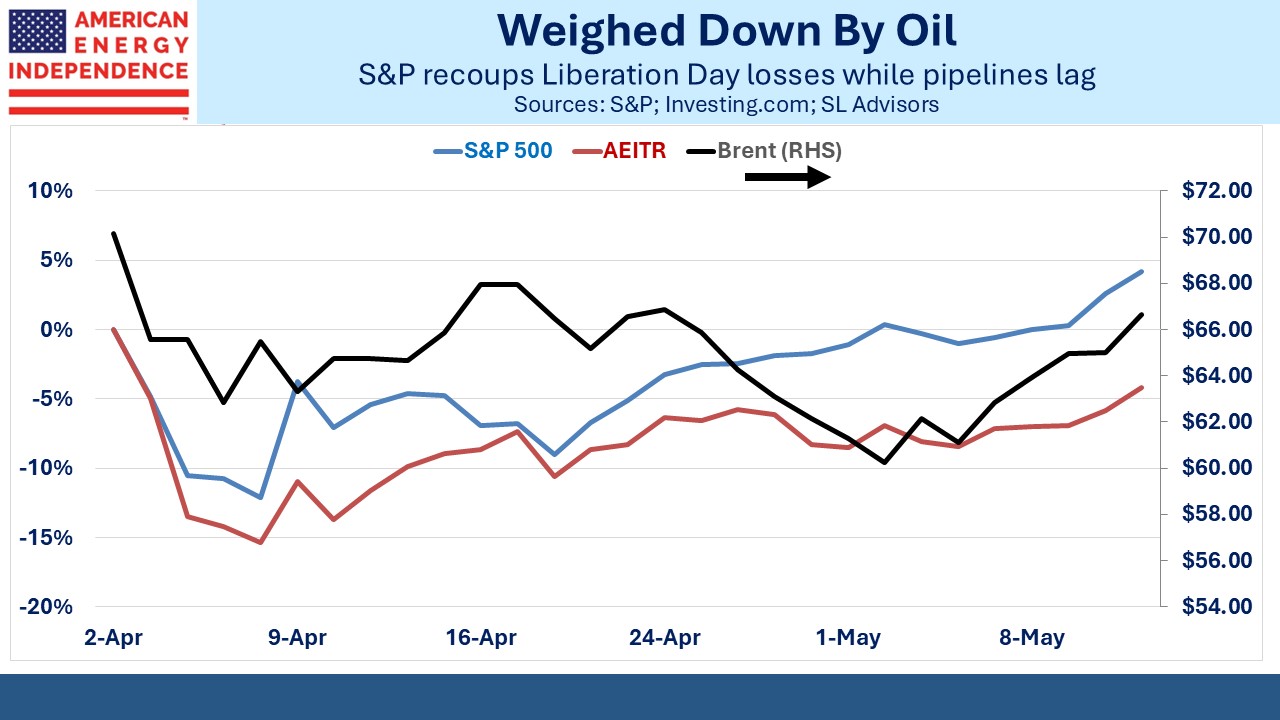

When conflict occurs that might disrupt global oil supplies, portfolios that include an allocation to midstream energy infrastructure usually enjoy some modest protection. Crude traded up 14% on Thursday night as the Israeli attack unfolded. Some opportunistic hedging by producers trimmed those gains during the day. Energy stocks as usual responded positively.

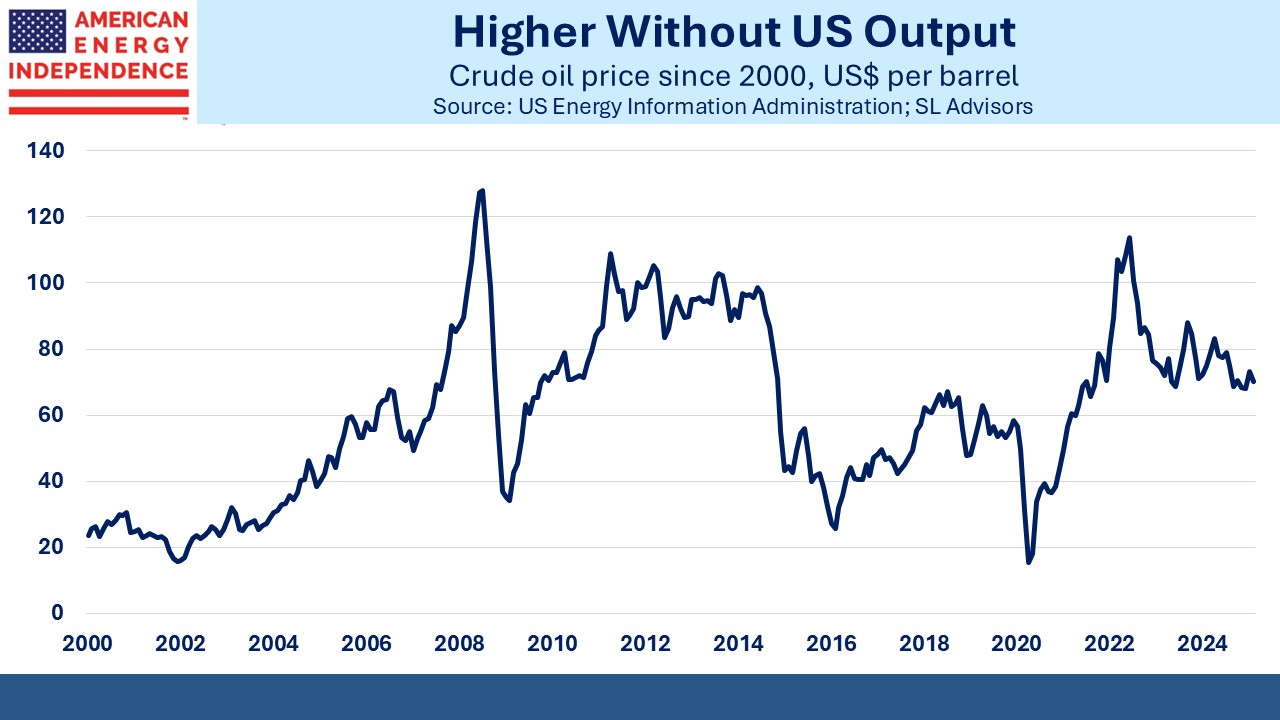

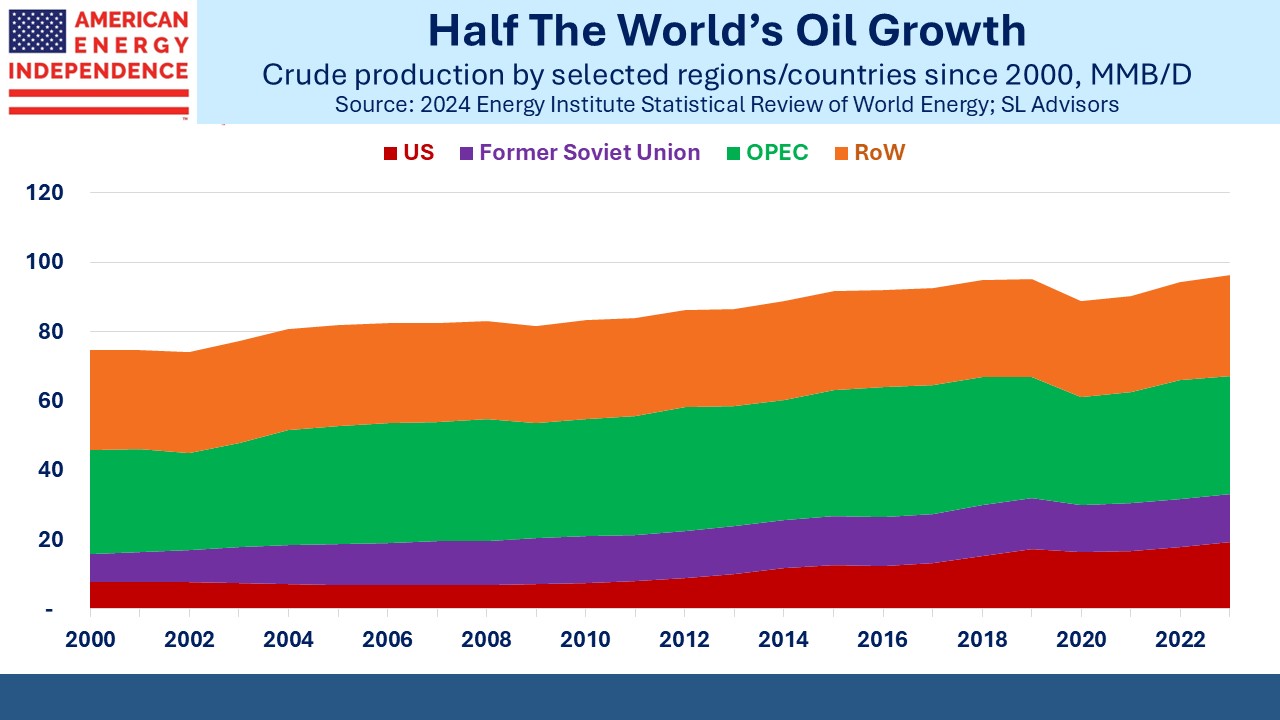

The effect on midstream is more subtle. The sector is less responsive to commodity prices than in the past. It may enjoy a brief lift as positive energy sentiment spills over, but management teams don’t generally obsess too much about oil. This time may be different, because weak crude prices have constrained US oil production with some even forecasting it may drop next year. Friday’s higher prices benefitted Oneok and Plains All American, which might see more robust volumes through their systems if higher prices persist.

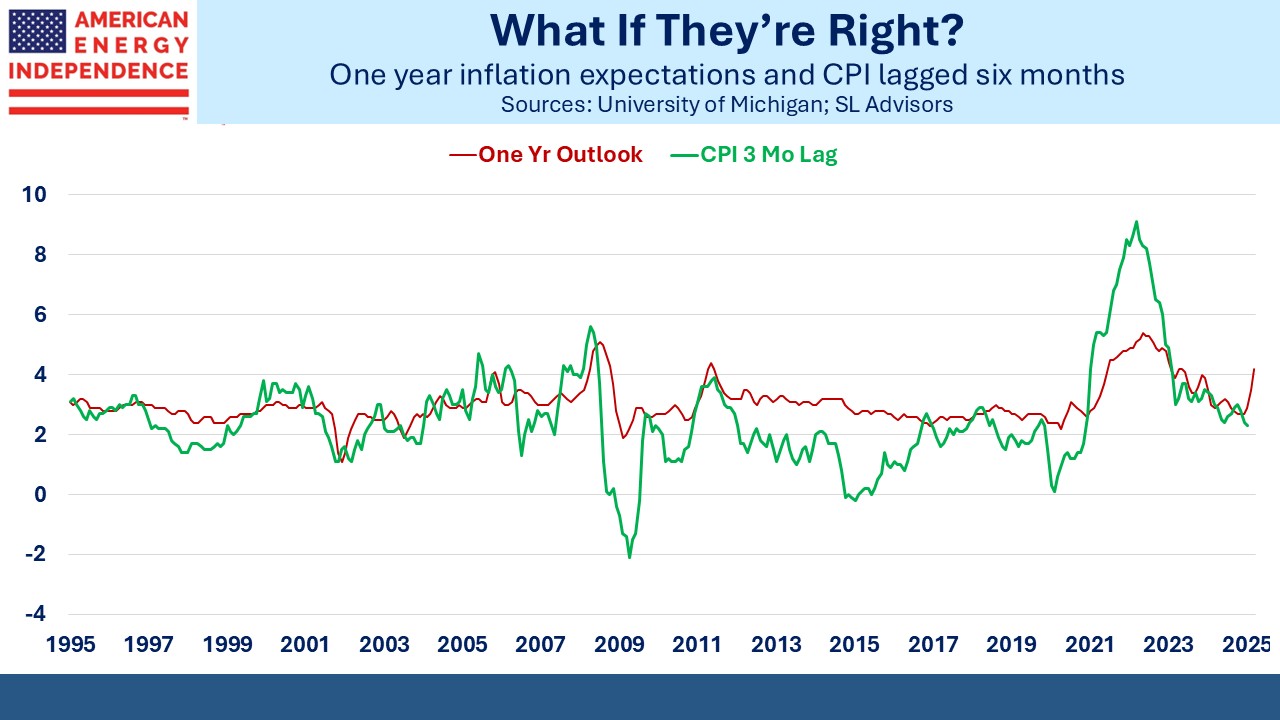

Crude weakness this year has also curbed inflation expectations. The partial reversal explains Friday’s weakness in bonds. According to Wells Fargo, around half the midstream sector’s EBITDA is tied to contracts that allow price hikes linked to the PPI. In 2022 this was a significant benefit since midstream companies were able to raise prices in line with inflation. This supported the sector’s 22% return that year, a sharp contrast with the S&P500’s -18% return as the Fed tightened rates.

On Friday, midstream outperformed the S&P500 by 1.5%. But the diversification benefits of midstream last for more than a couple of days. Most investors have significant technology exposure, since it’s now almost a third of the S&P500. Several articles have been written about the evolution of the market’s leading index towards a basket of growth stocks.

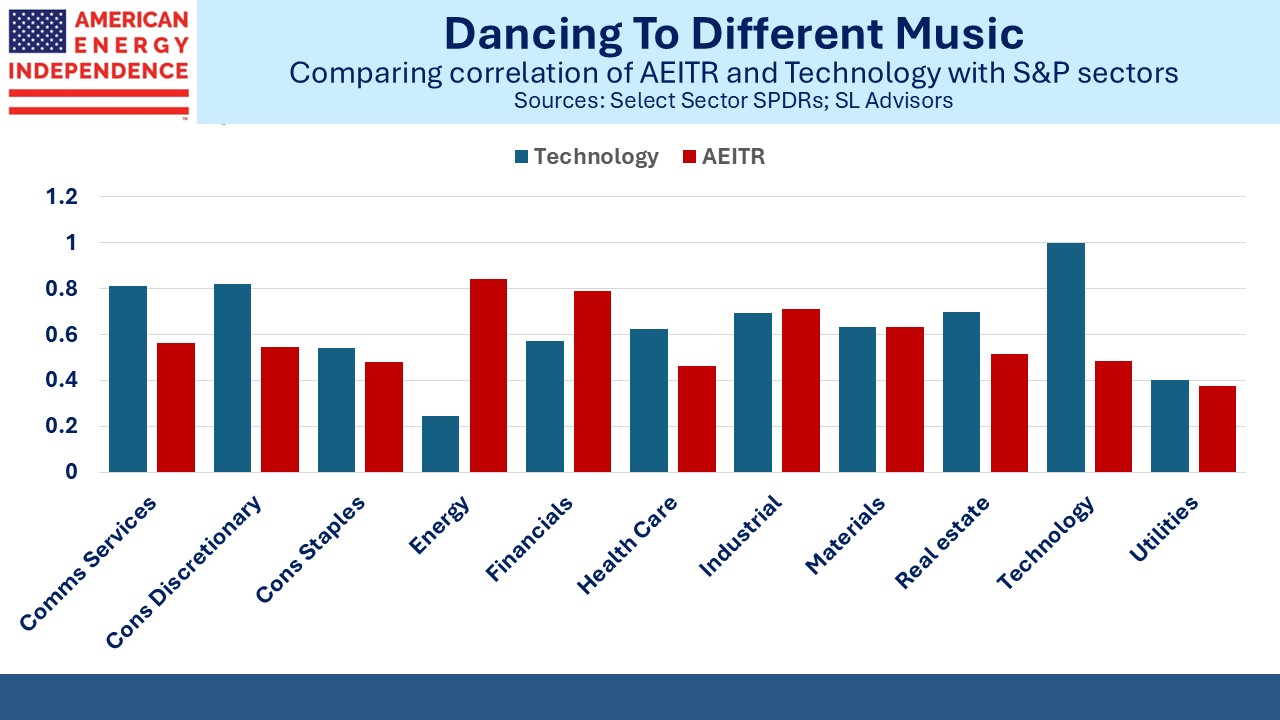

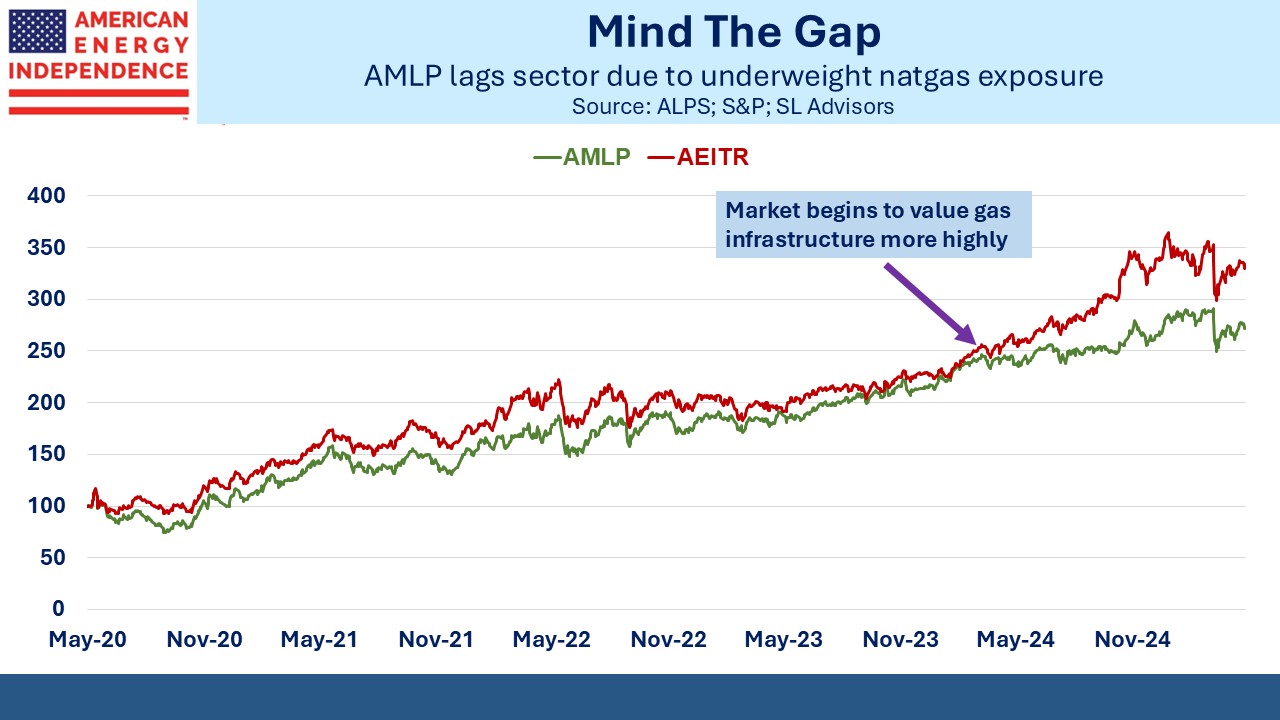

Midstream energy infrastructure, defined here as the The American Energy Independence Index (AEITR), is less correlated with most S&P500 sectors than is the Technology sector. The two sectors where this is significantly not the case are the energy sector itself and financials. It has only half the correlation to the S&P500 as Technology, unsurprisingly given the shifting composition of the index. But for Communication Services, Consumer Discretionary and Healthcare the AEITR is also less correlated to these sectors than is the Technology sector.

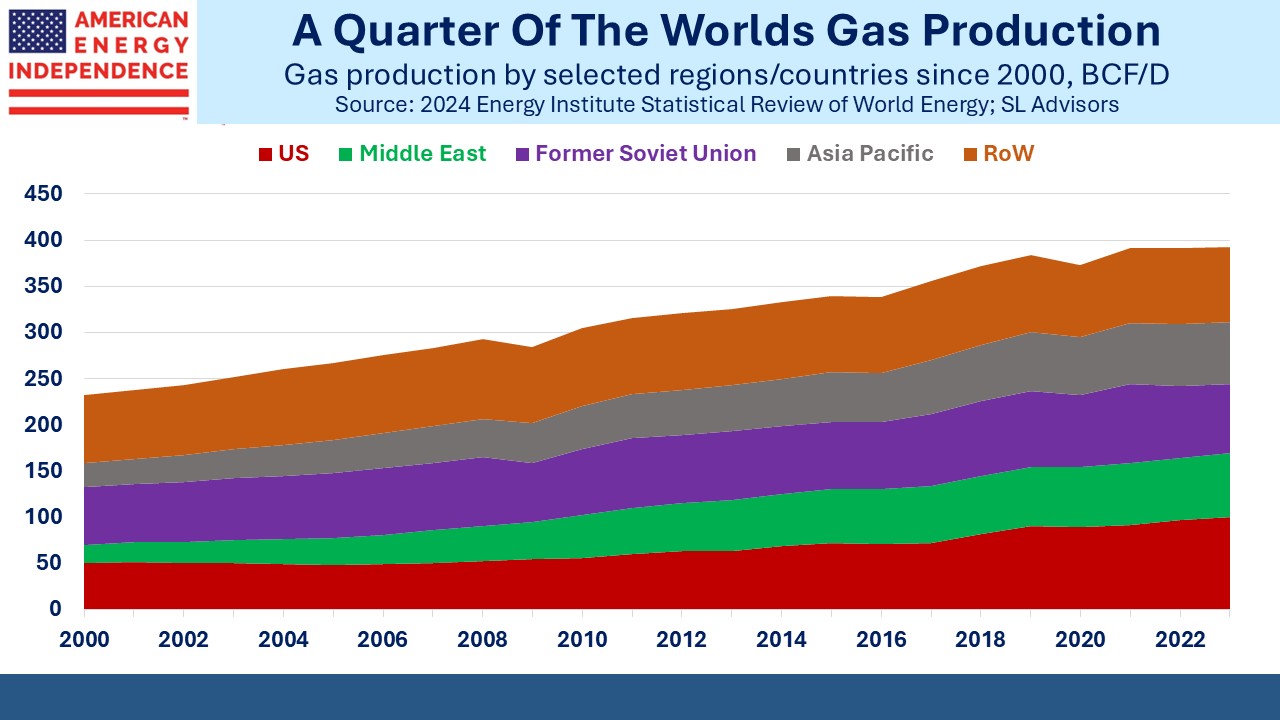

It also doesn’t hurt that when markets are considering whether Israel will strike Iran’s energy infrastructure, the AEITR is all in North America well out of harm’s way. The Strait of Hormuz is widely recognized as a chokepoint for Middle East oil exports. Less attention is paid to the vulnerability of trade in Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG), 20% of which passes through the same stretch of water from Qatar and the UAE.

Last year Qatar exported 80 million metric tons of LNG, making them the third biggest exporter behind the US and Australia, with 19% of global trade. 70% of Qatar’s exports go to Europe and 20% to Asia. We were surprised that so far neither of the regional LNG benchmarks have responded much to the same concerns that have boosted oil prices, even though buyers have limited alternatives.

US LNG exports don’t face the risk of a Middle East war disrupting supplies. We think that the reliability of the US as a supplier could become more highly valued as buyers contemplate worst case scenarios for the product.

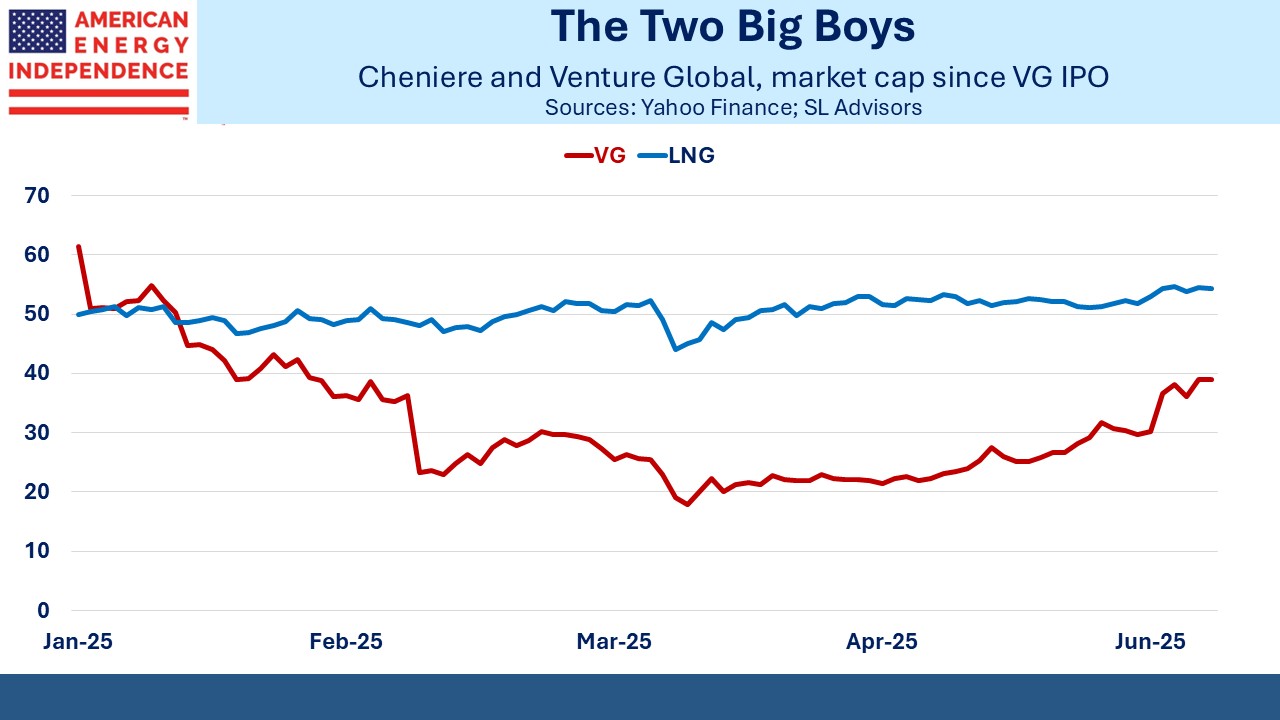

We still see attractive opportunities among LNG stocks.

Venture Global received a boost last week when they withdrew their application to build the Delta LNG terminal, because they believe they can achieve an equivalent capacity increase by expanding their Plaquemines facility. VG has earned the respect of many for their relatively fast project execution.

NextDecade announced that they have reached agreement with Bechtel Energy to build Trains 4 and 5 of their Rio Grande LNG terminal. We think it’s possible that NEXT will make a Final Investment Decision (FID) to go ahead with this second stage before the end of the year.

Israel halted production at its Leviathan natural gas field, operated by Chevron, due to security concerns. Within hours Egypt, which depends on gas imports, began shutting factories.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine made energy security a higher priority. The war in the Middle East will likely add to that. We continue to think that US LNG exports will be highly valued by America’s friends and allies around the world.

For many investors, midstream appeals because of the stable dividends well covered by cashflow and declining leverage. Few consider the diversification benefits of an allocation or the sector’s resilience to disrupted energy supplies. The events of recent days have highlighted these additional positive features.

We have two have funds that seek to profit from this environment: