Hedge Fund Fees May Be Even Higher Than I Thought

The entire eastern seaboard of the United States is waiting tentatively for Hurricane Sandy’s arrival. Our patio furniture has been safely stored indoors. Batteries and candles are well supplied in anticipation of the inevitable power loss, and with preparations done we wait for the slowly arriving worst storm many of us have ever seen. So naturally, I turned to Gretchen Morgensen’s article in the New York Times today (“The Perils of Feeding a Bloated Industry“). Gretchen focuses on the costs of active money management and questions whether society has received much benefit from the increasing share of GDP that is represented by the financial services industry. It’s a worthy question and one that society has a right to ask given events of the past few years. In this she highlights a recent academic paper (“The Growth of Modern Finance” by Robin Greenwood and David Scharfstein) and in clicking on the hyperlink to this paper I was fascinated to see included an estimate of hedge fund fees.

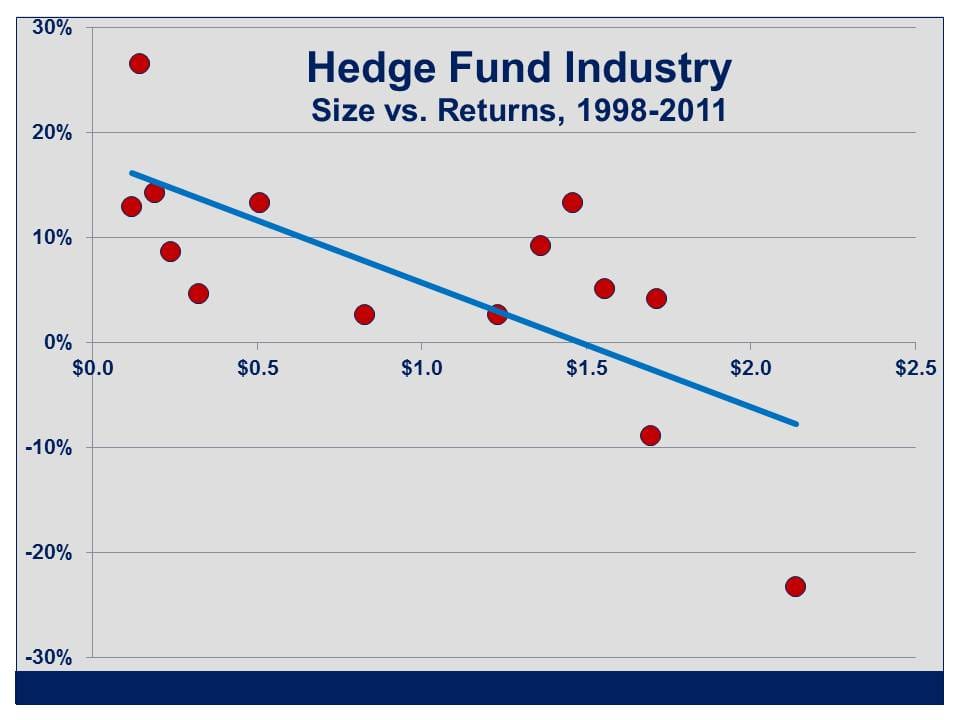

Readers of my book The Hedge Fund Mirage will be familiar with my assertion that fees had consumed fully 98% of the investor profits in excess of t-bills through 2010. I even posted a pie chart illustrating the fact on my blog a few months ago. If you look at the chart you’ll note that the 2% sliver of pie denoting the clients’ share only lasts through 2010. Including 2011 wipes it out, but since I couldn’t conceive of a negative slice of pie in two dimensions the schematic had to run only through 2010.

The Alternative Investment Managers Association (AIMA) in London, whose sorry task it is to defend past practices of their paymasters in the hedge fund industry, has made a couple of attempts to respond to the chief finding of my book (that all the money ever invested in hedge funds would have been better off in treasury bills), but even AIMA has not attempted a robust defense of the 2 & 20 fee structure. AIMA’s recent paper was effectively demolished here. They do rather lamely offer that fees have amounted to 3.5% per annum, and even though that sounds high to most people it’s based on the same flawed structure used throughout their paper which relies on a hypothetical investor with an equally weighted portfolio started in 1994. Whether such an investor actually exists or not is another matter – I think it’s more realistic to measure how ALL the money has done, and in 1994 while investors did well there weren’t that many of them.

So I was interested to note that in the Greenwood and Scharfstein paper referenced above, hedge fund fees are found to be similar to my numbers. For example, the paper states that hedge fund fees reached $69BN in 2007, remarkably close to the $70BN estimate that I found and included in my book. Greenwood and Scharfstein weren’t focused on hedge fund fees necessarily in their paper, and they make a good point that active management can lead to more efficient security pricing and greater diversification which ultimately lowers the cost of capital for companies (you’ll have to read their paper to see why this makes sense, but I think it does). So they’re not highly critical of hedge funds (although they feel fees are too high) and they reach a similar place to me on fees.

But then I came across an earlier paper by Kenneth French in the 2008 Journal of Finance (“Presidential Address: The Cost of Active Investing“) and although Kenneth French focuses just on equity long/short hedge funds he estimates that the average annual drag of fees from 1996-2007 is 6.5%, virtually double what AIMA rather hopefully suggested. In fact, if I’d used his methodology I would have come up with even higher estimates in my book.

If some observers feel I’ve treated hedge funds too kindly on the fee issue, I can now understand why. It seems academic papers are all around showing that it’s been at least as bad as I’ve described.