Dwindling Pipeline Capacity Causes FOMO

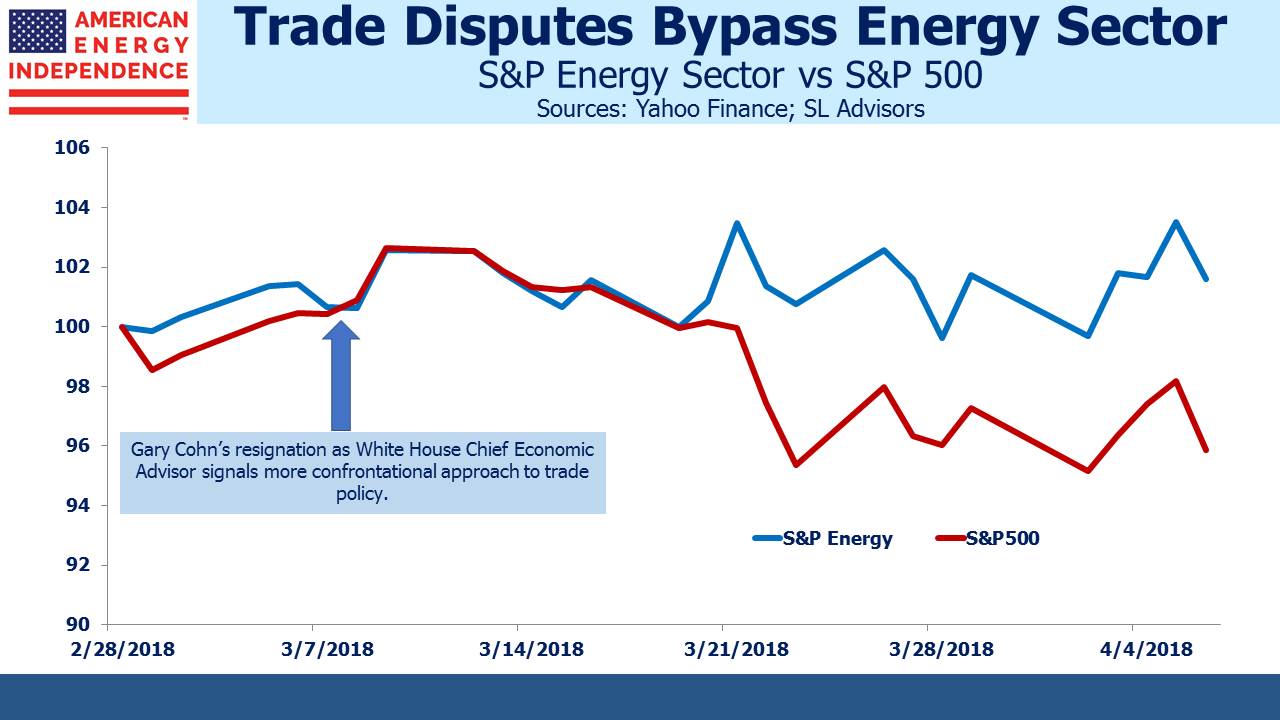

FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) hasn’t been much of a problem for energy infrastructure investors over the past year or so. Feelings of WAIL (Why Am I Long?) and (ahem) WTF have been far more common. So the recent rally in the sector has led many investors to enquire why. Earnings only began to be released on Wednesday when Kinder Morgan (KMI) announced a 60% dividend increase and $500MM of stock repurchases since December. Although the dividend hike was expected, the stock nonetheless gained ground. KMI’s 2014 simplification, when they moved from four public entities to one, heralded the conflict between the old and new business model.

Shale Revolution-induced growth opportunities pursued by management collided with the desire of income-seeking investors for steadily growing cashflows (see Will MLP Distribution Cuts Pay Off?). An adverse tax outcome and two distribution cuts followed for original investors in Kinder Morgan Partners. MLP simplification became synonymous with abuse of your core investors, at least until Tallgrass (TEGP and TEP) recently managed to execute one that was well received.

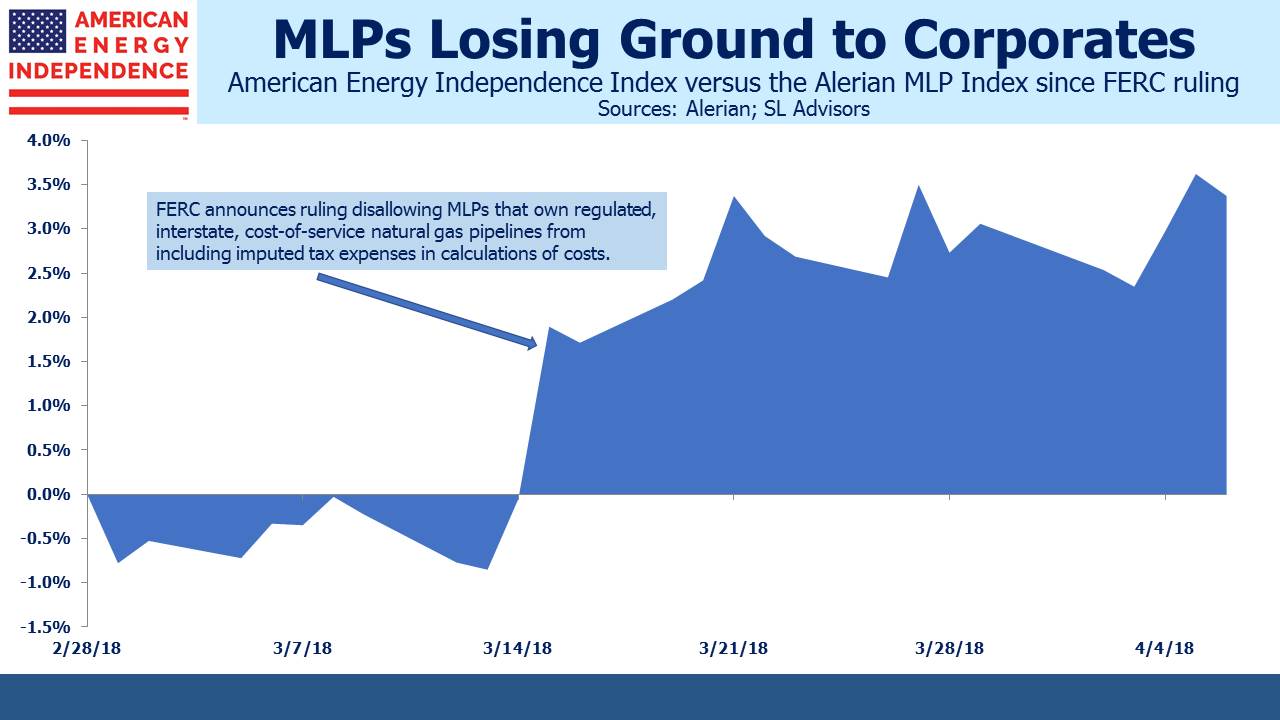

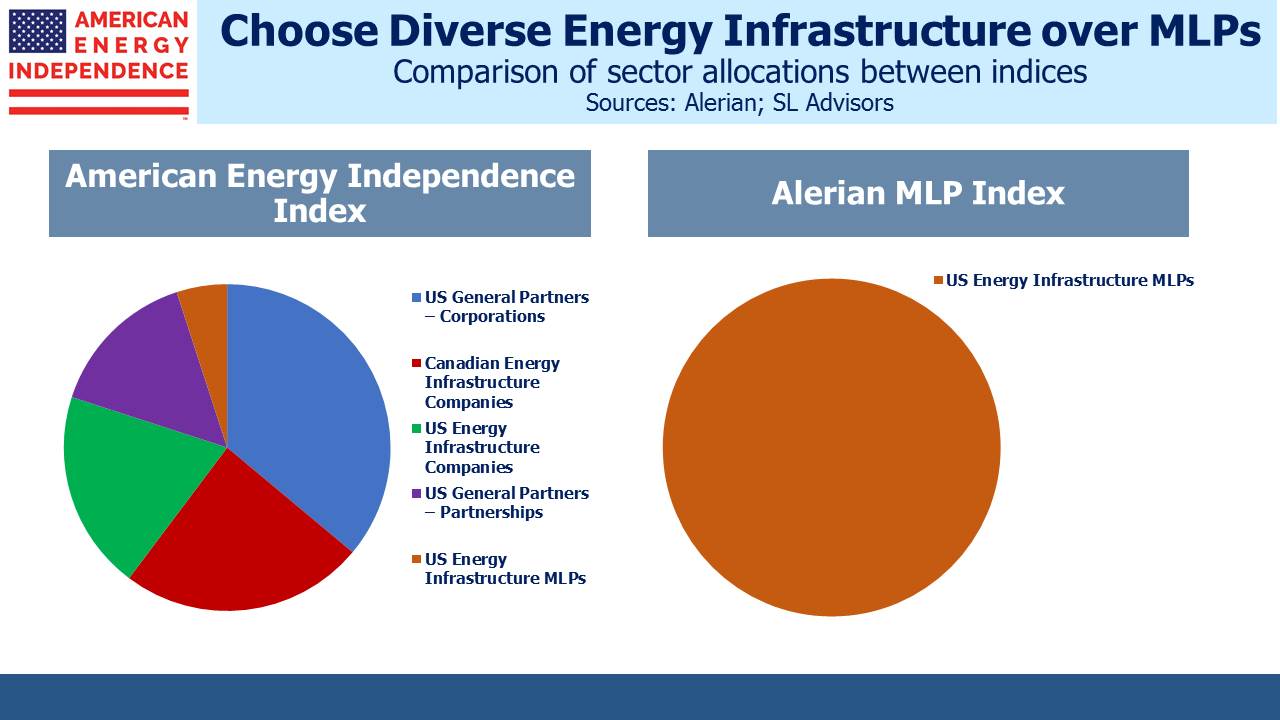

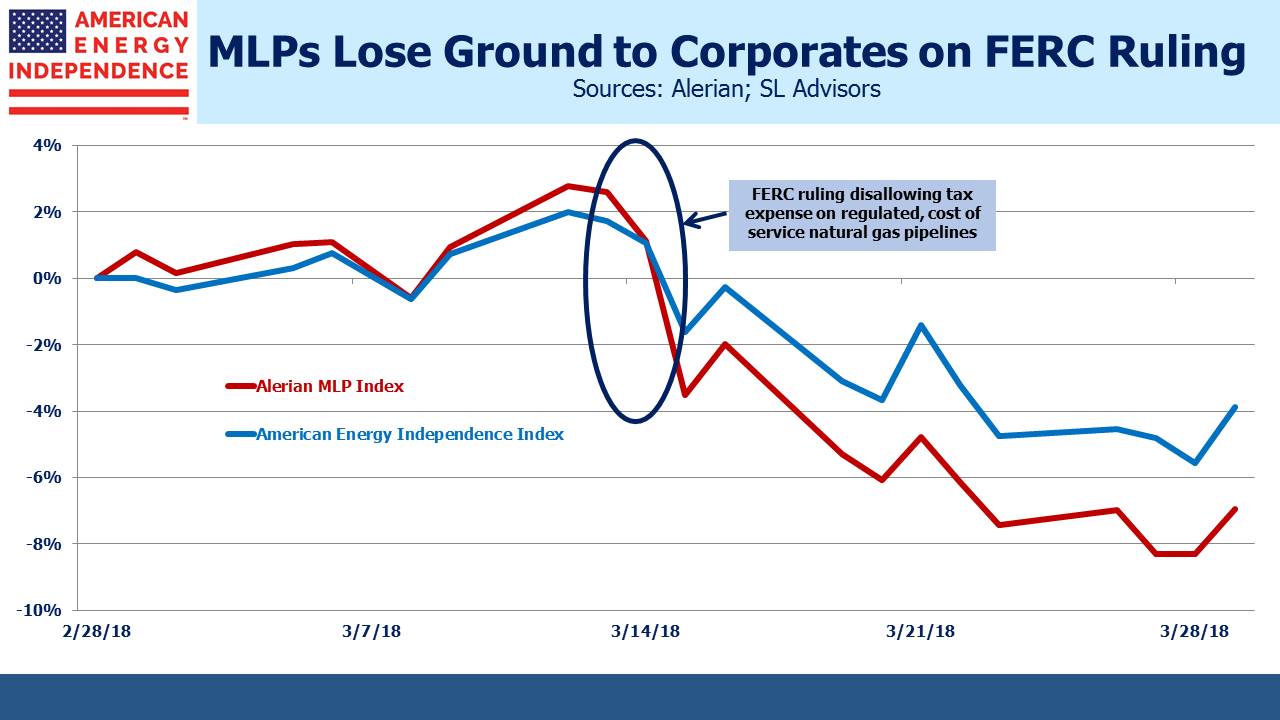

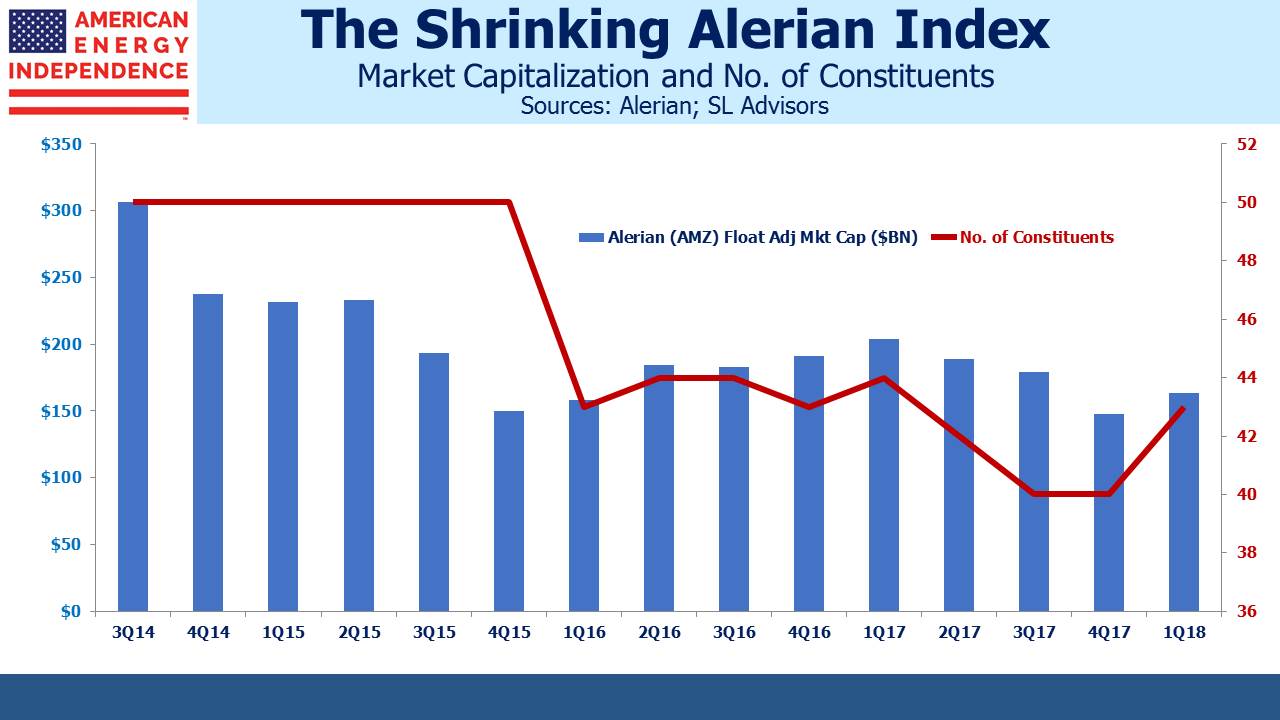

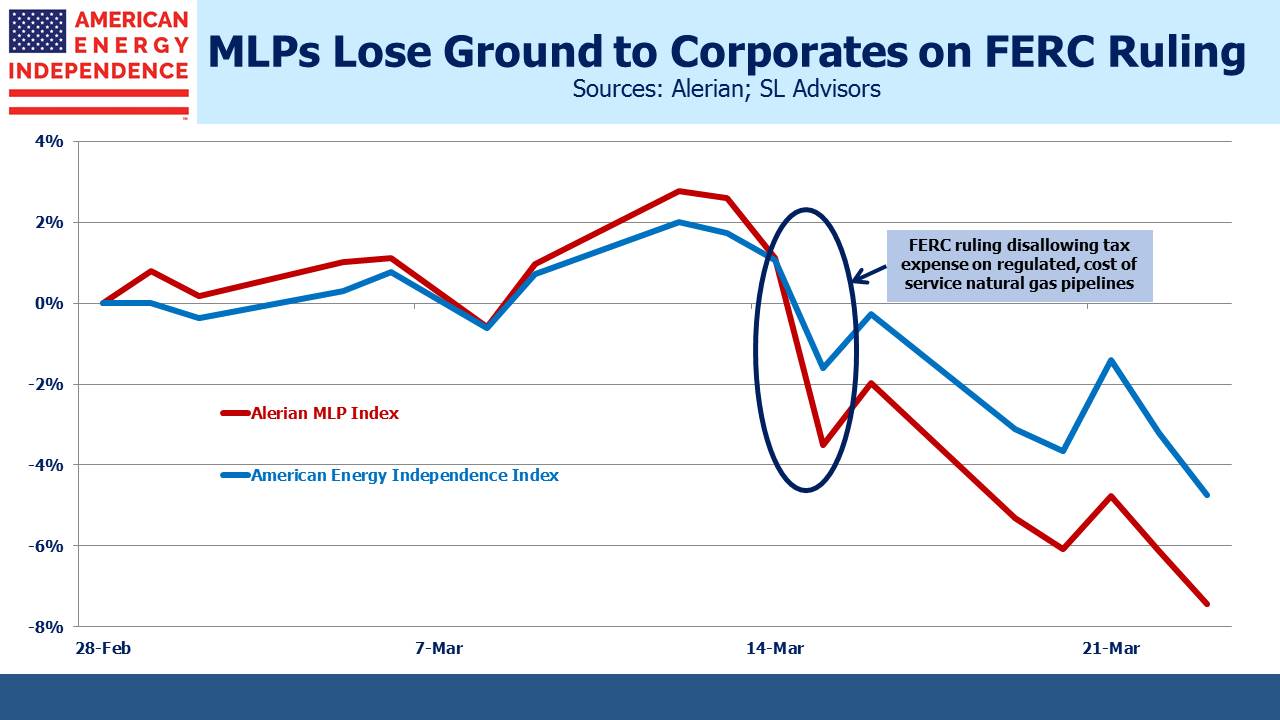

Nonetheless, the persistent high yields on MLPs betray the skepticism of their traditional investor base of older, wealthy Americans. Last year Oneok (OKE) combined with its MLP Oneok Partners, inflicting a KMP-type tax bill on long-time MLP holders. One friend of mine held its predecessor Northern Border Partners from the 1990s, and received an unexpected tax bill on deferred income recapture that was timed to suit OKE, not him. Such investors are not about to commit new money to MLPs. This is the problem facing MLPs but not corporations. MLPs are cheap, but they’ve alienated their core investor base, which is already narrow. This is why investors need to look for broad energy infrastructure exposure including corporations, and not be limited to MLPs (see The American Energy Independence Index). KMI’s $500MM stock buyback would not have happened when they were structured as an MLP.

Substantive developments to explain the rally are few, although Saudi comments favoring $80 oil have helped. Technical analysts have noted that energy infrastructure shows signs of bottoming, something not heard since 2016. Energy stocks are gaining more airtime on CNBC. More tangibly, on Wednesday, the WSJ’s Is the U.S. Shale Boom Hitting a Bottleneck gathered substantial attention by suggesting, “…the U.S. shale boom appears to be choking on its own growth…”

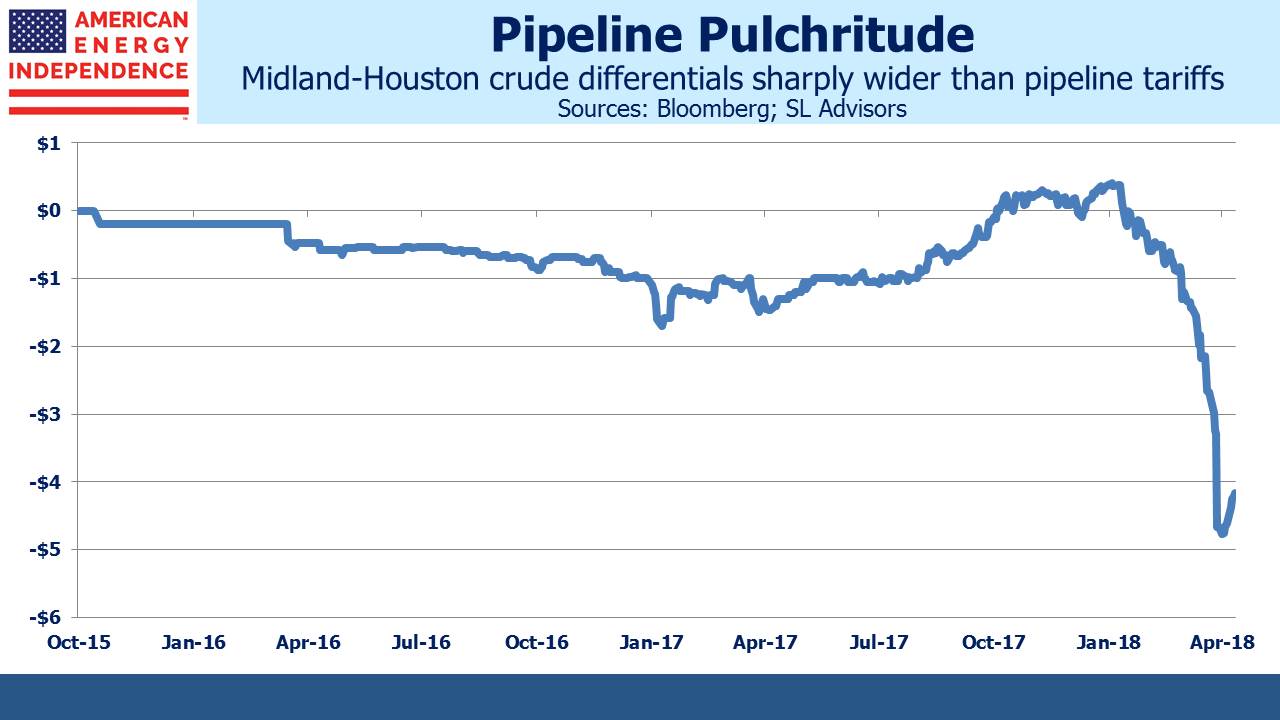

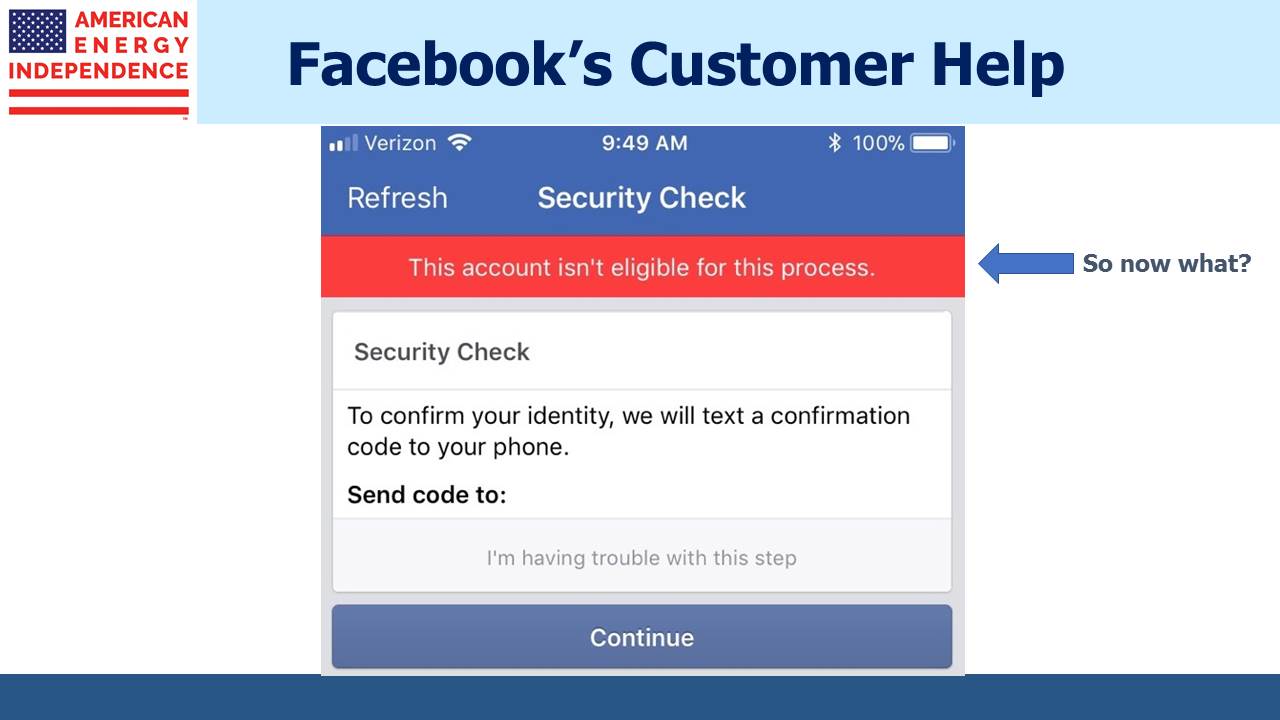

The article included a chart (reproduced here) that is a true object of beauty to any pipeline owner. The problem of sharply growing crude oil production in the Permian is testing the limits of take-away pipeline capacity. Crude oil located in Midland is usually worth less than in Houston, where it’s conveniently near refineries and export facilities. The price difference is typically going to be limited by the cost of pipeline transportation, which is around $2-3 per barrel. Permian output is currently 3.1 Million Barrels per Day (MMB/D), with pipeline take-away capacity of 3.2MMB/D.

The price differential has widened beyond the pipeline tariff because not all the crude wishing to travel to Houston can get in a pipeline. Some is moving by rail (around $8 per barrel) while truckers charge from $10 to as high as $15-20 (truck drivers are in high demand in Texas).

This is a problem for Permian oil producers, since the increased cost of getting their product to market eats into margins. However, it’s a profit opportunity for pipeline owners, since the portion of their capacity that is sold at market rates is now much more profitable. Bottlenecks are good for infrastructure owners. They make money from regional price differentials in excess of the costs of storage and transportation. When Plains All American (PAGP) cut their distribution last year, they blamed it on a collapse in their Supply and Logistics division as regional price differentials were boringly close to transportation costs, minimizing arbitrage opportunities.

Some additional pipeline capacity can be squeezed out through more efficient utilization. Drag reducing agents (millions of tiny polymer string segments) can be mixed with crude which, through the magic of hydrodynamics, reduce turbulence as the liquid travels. But meaningful new capacity isn’t expected until 2H19, which on current trends should maintain the steep Midland-Houston discount and support continued higher pipeline tariffs. Among the beneficiaries of this are PAGP, Energy Transfer Equity (ETE) and Enterprise Products Partners (EPD).

We are invested in EPD, ETE, KMI, PAGP and TEGP