Energy infrastructure roared higher during the first six trading days of January. After four days, the sector had recovered December’s losses. Two days later, it had almost recouped all of 2018. It was a complete reversal of last month, when slumping equity markets dragged pipeline stocks lower.

It’s looking increasingly likely to us that automated trading strategies relying on complex algorithms (“algos”) are at least part of the reason.

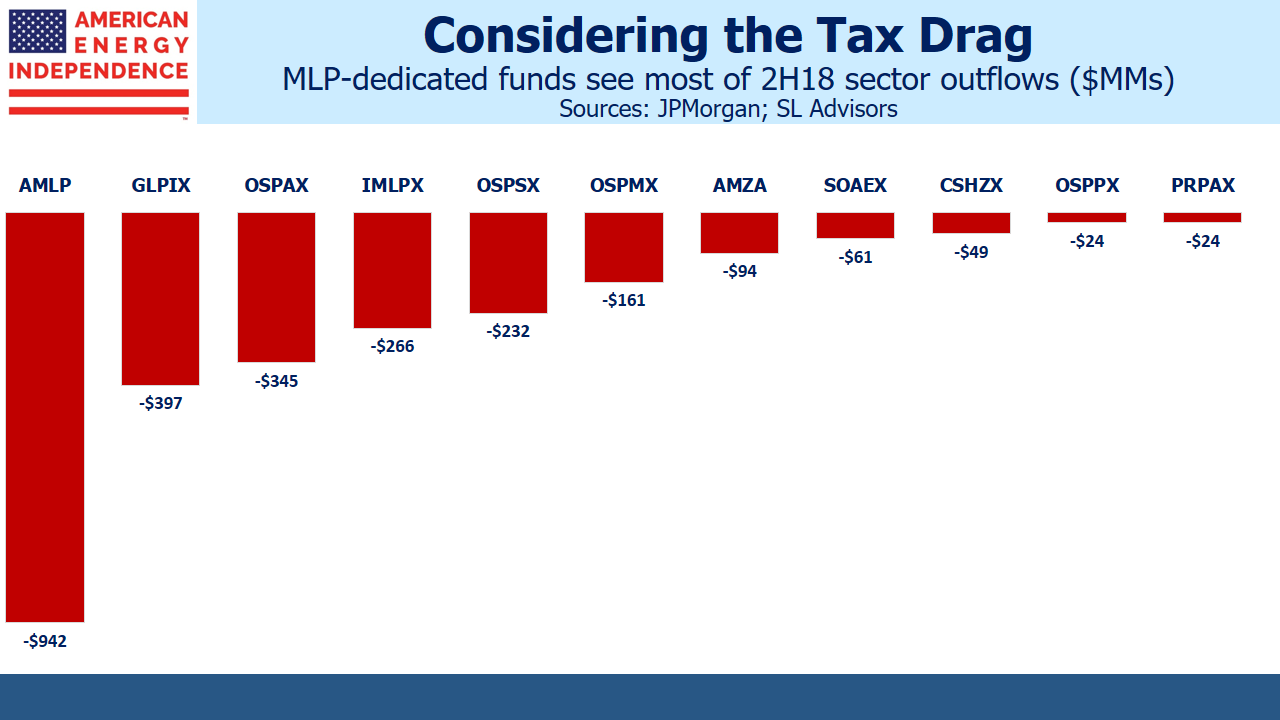

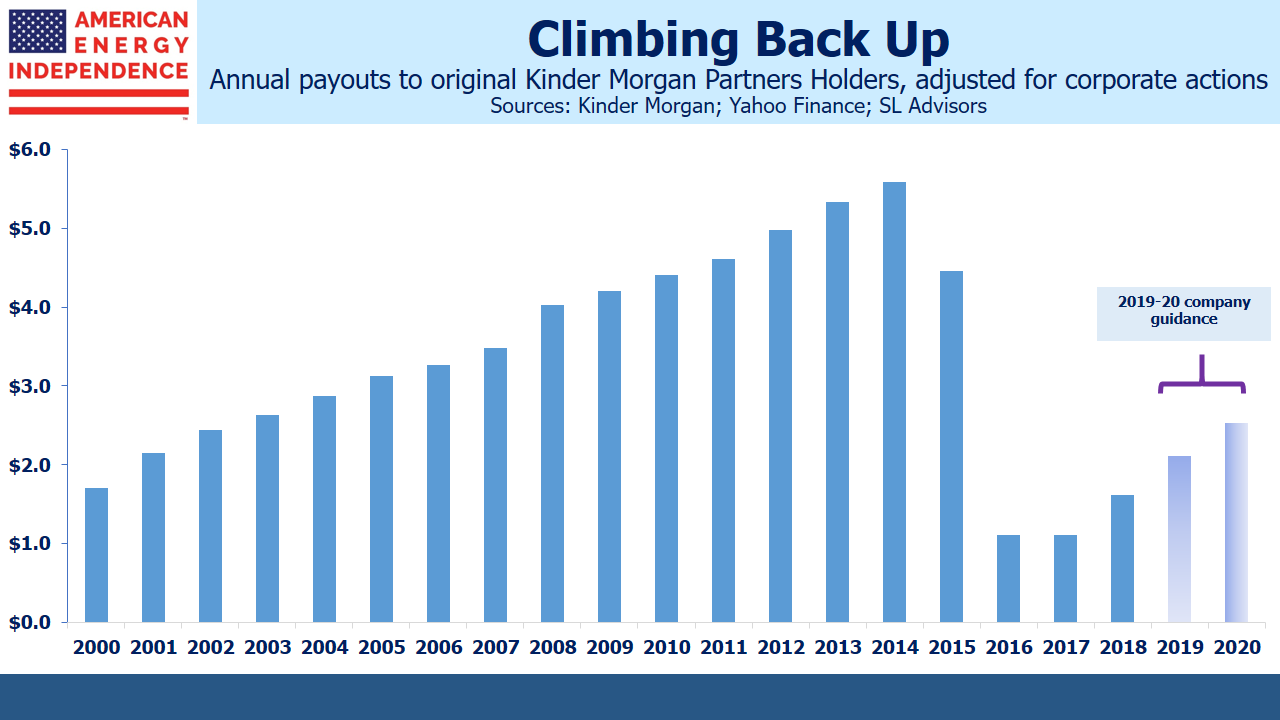

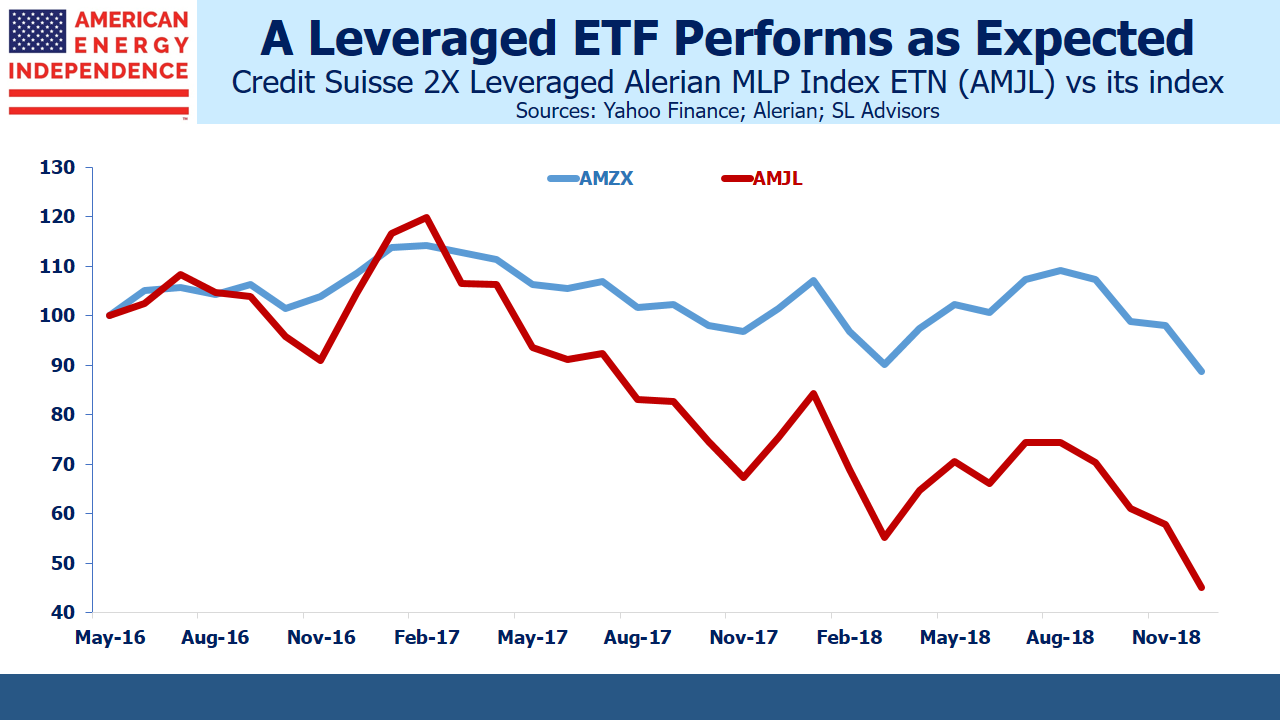

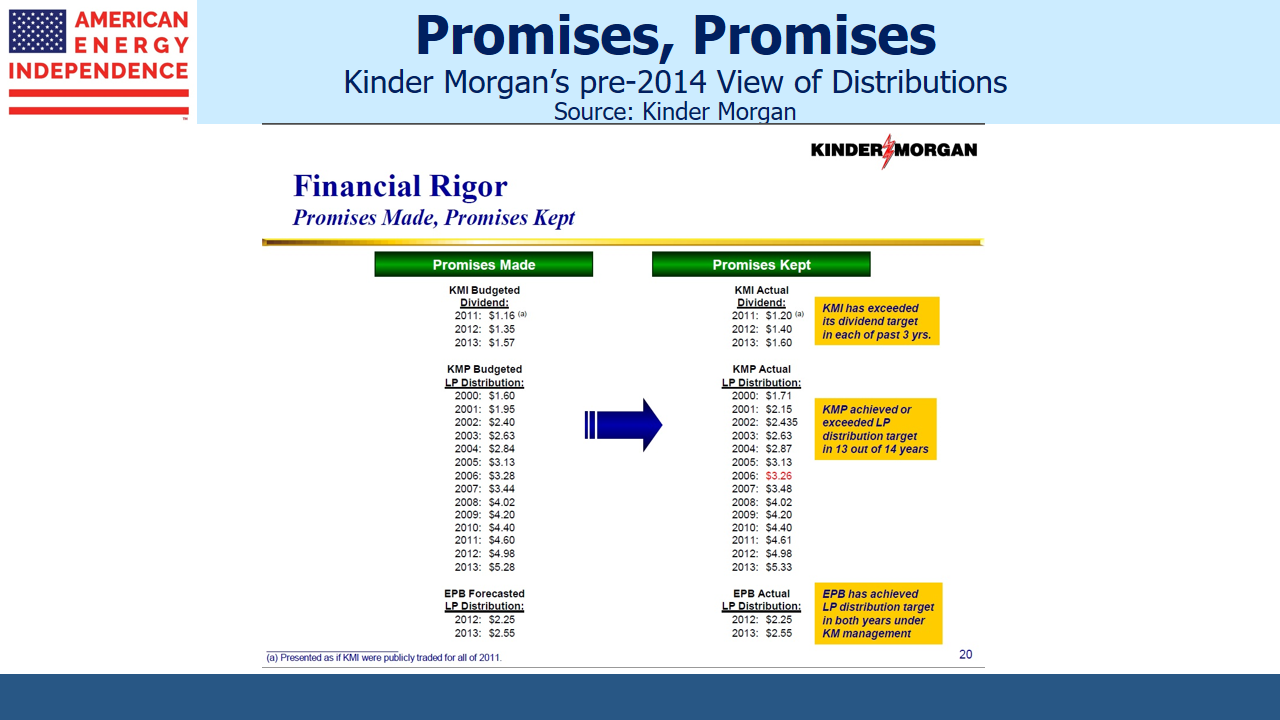

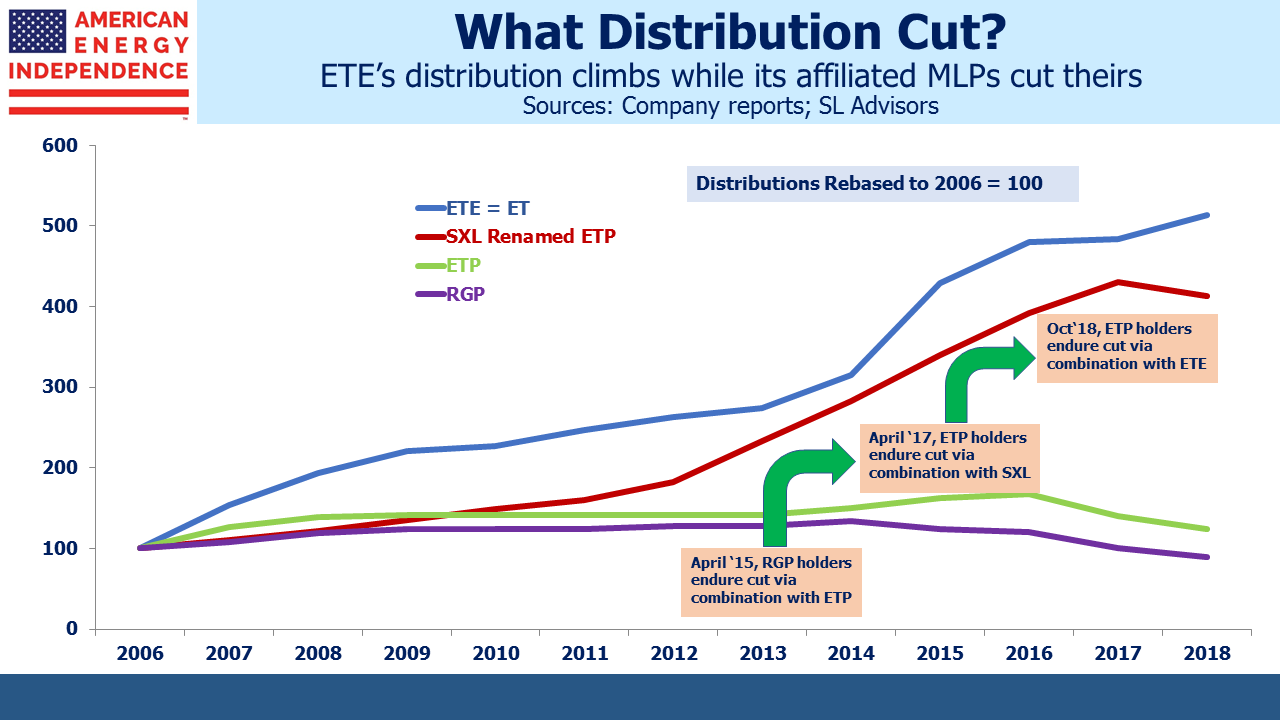

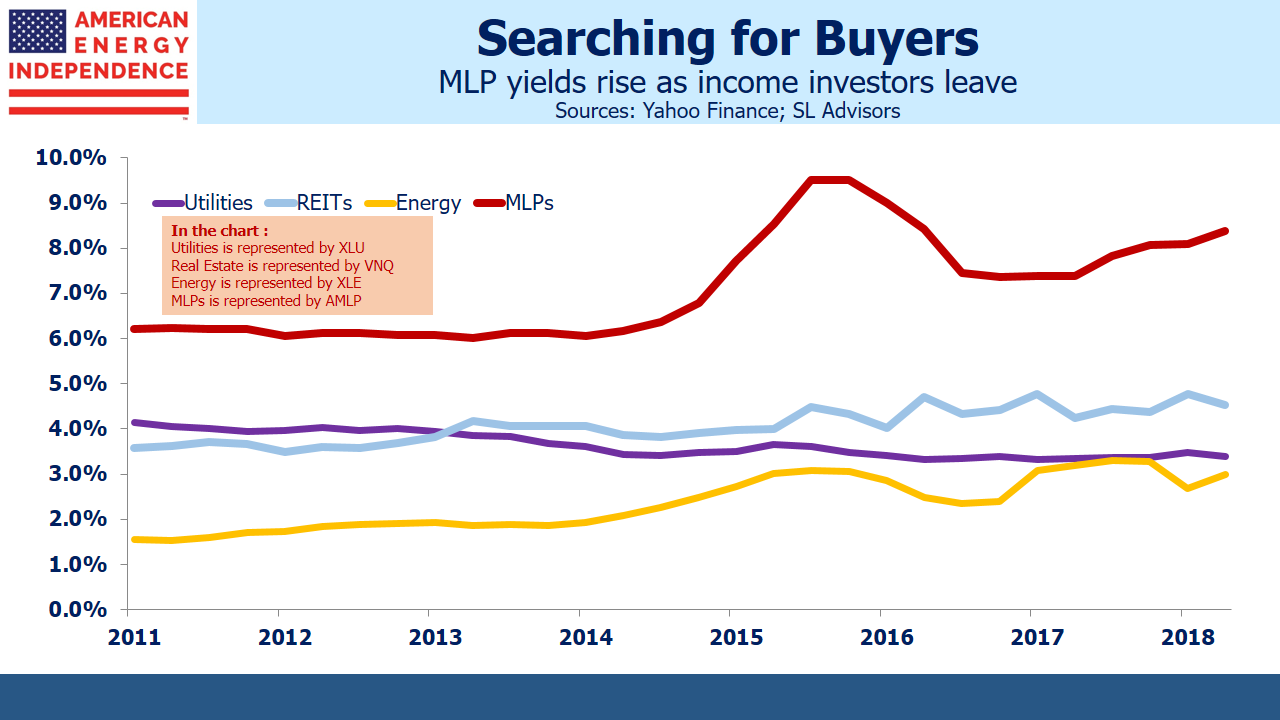

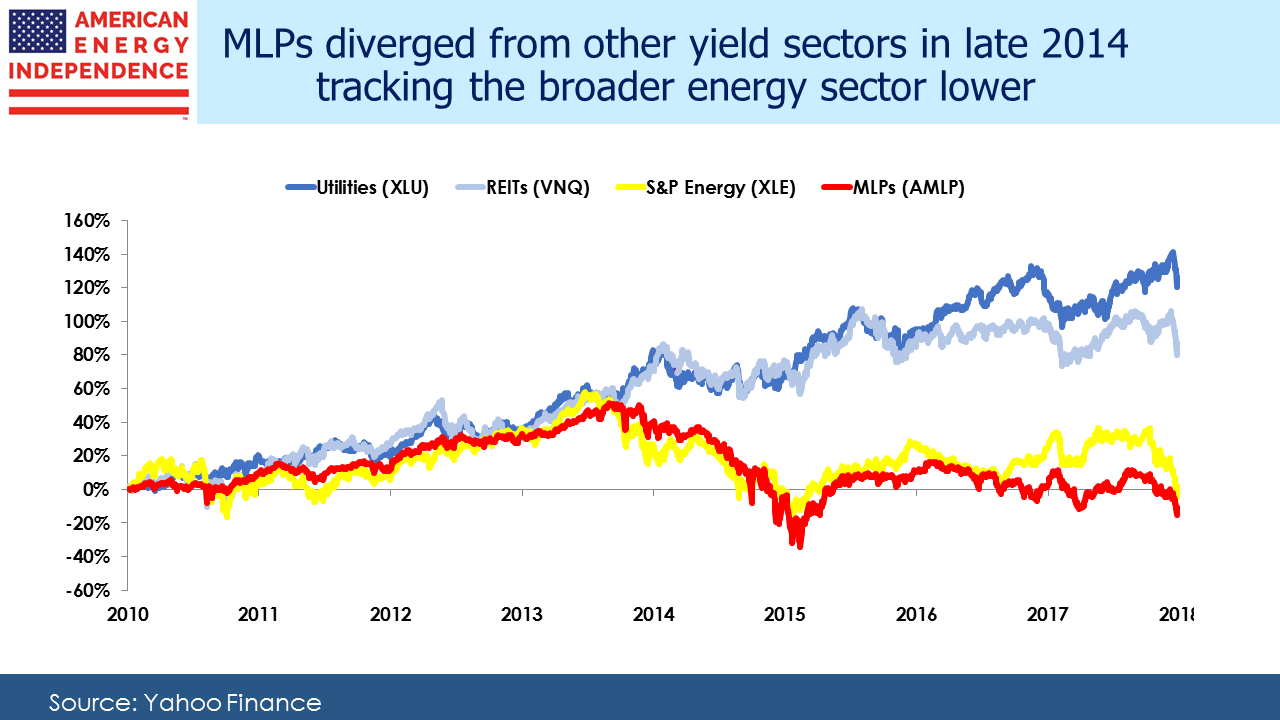

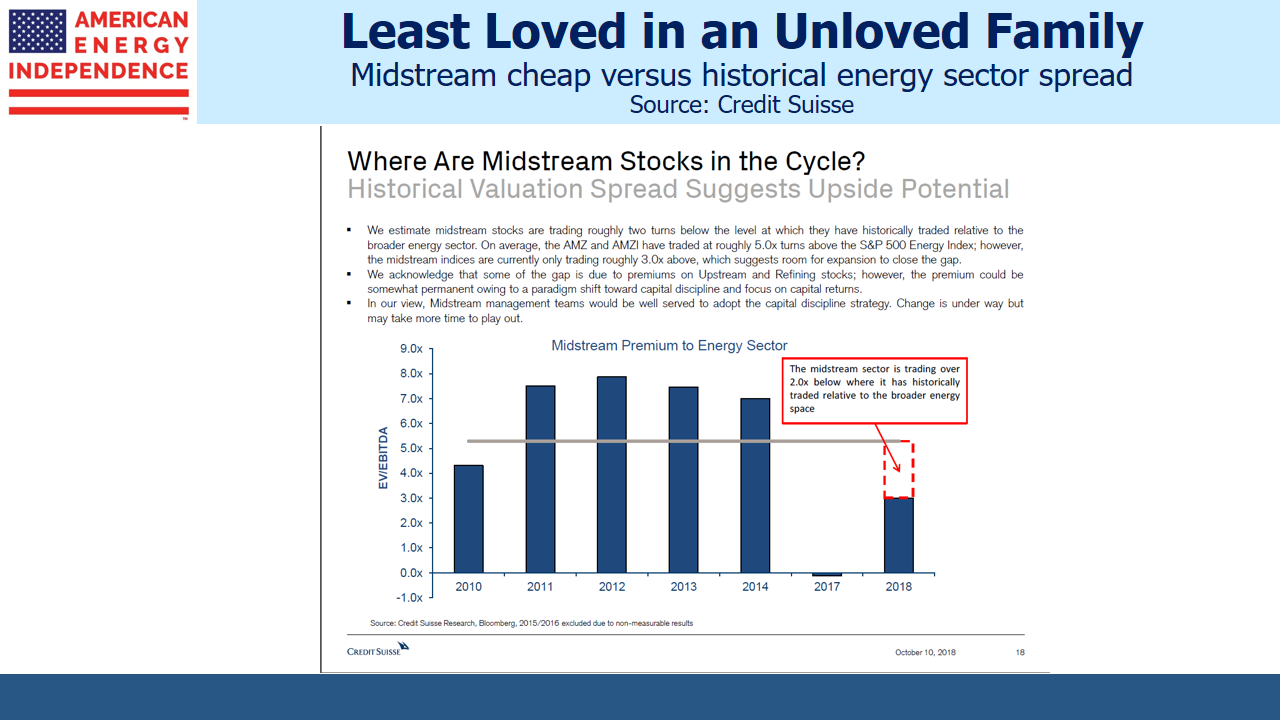

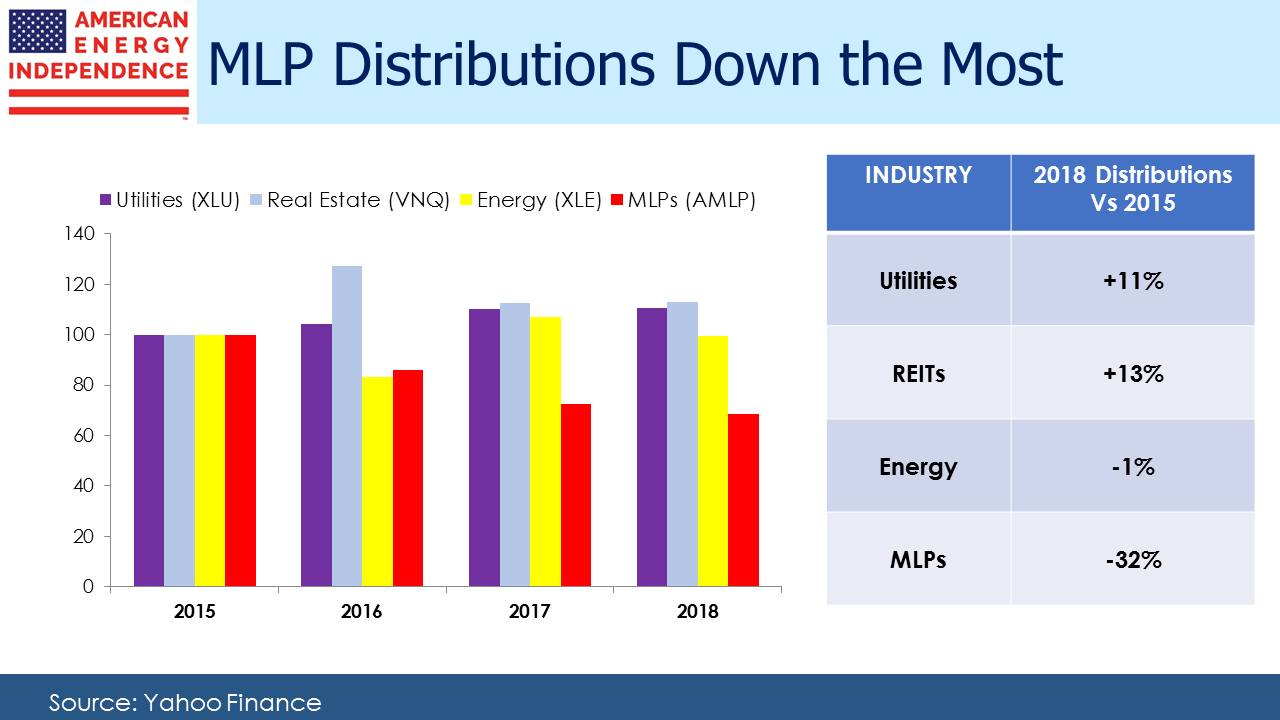

Last year MLPs had already been laboring under the weight of serial distribution cuts. For example, AMLP’s payout is down by 34% since 2014. Incidentally, this must be the worst performing passive ETF in history. Since inception in 2010, it has returned 4% compared to its index of 25%. Its tax-impaired structure is part of the reason (see Uncle Sam Helps You Short AMLP).

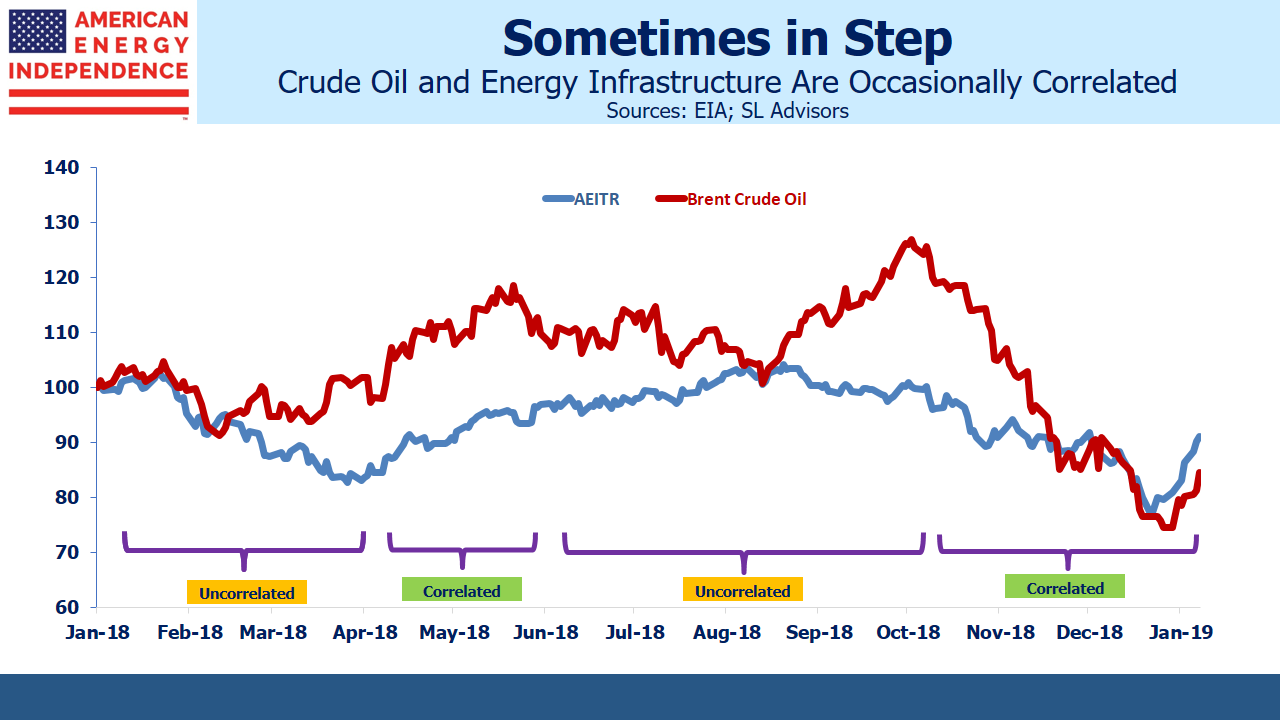

For the first nine months of last year, crude oil and energy infrastructure moved independently of one another. Investors who painfully recall the 2014-16 energy sector collapse complained that rising crude prices didn’t help, but as the chart shows, they rallied together in the Spring but parted company in late Summer as the oil market started to anticipate the re-imposition of sanctions on Iran. Crude and pipeline stocks are intermittently correlated, because their economic relationship is weak. Crude sometimes drives sentiment, which can quickly change.

However, when crude dropped sharply following the Administration’s waivers allowing most Iranian exports to continue, energy infrastructure followed. Pipeline company management teams routinely show very limited cash flow sensitivity to commodity prices, and 3Q18 earnings reported in October/November were largely at or ahead of expectations. Nonetheless, an algorithm incorporating the 2014-16 history would expect MLPs to follow crude when it drops sharply, and would act accordingly. Trading systems bet on falling MLPs following crude, and sold.

In late December crude reversed, and trading systems at a minimum are closing out short pipeline positions if not going the other way. Hence the blistering early January recovery. The fundamentals were good in December, and remained so in January. Any change was imperceptible.

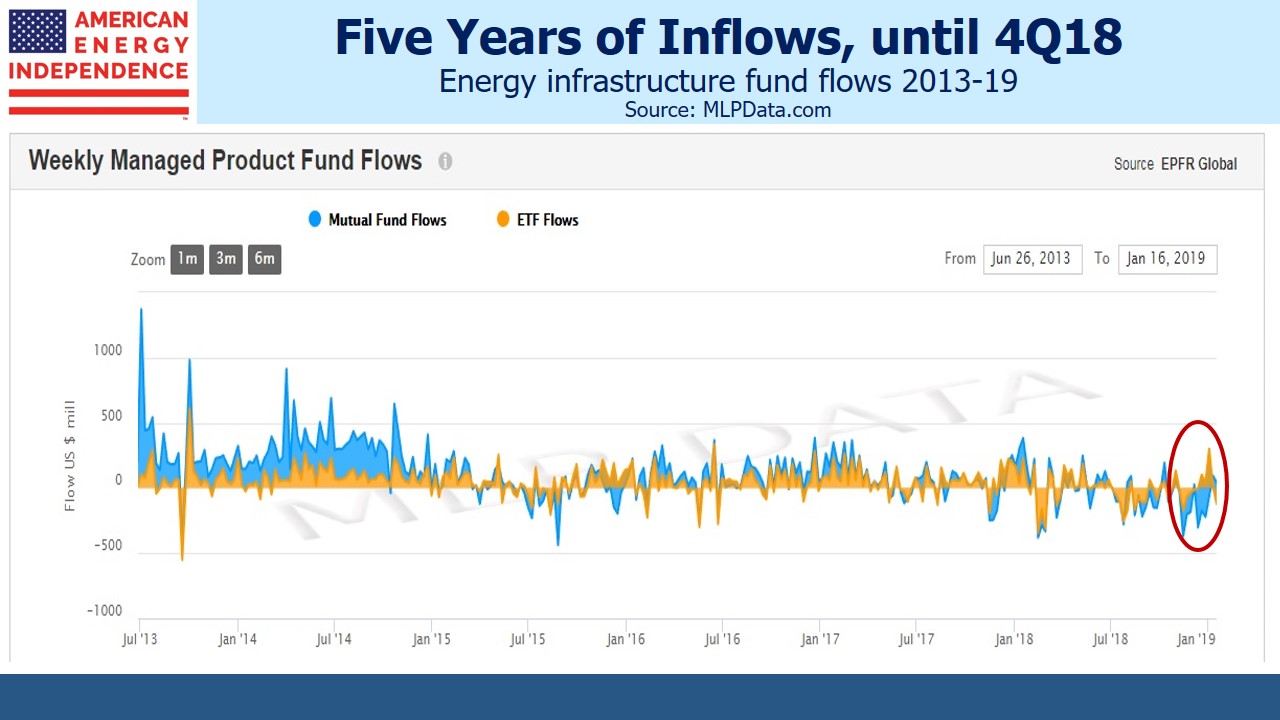

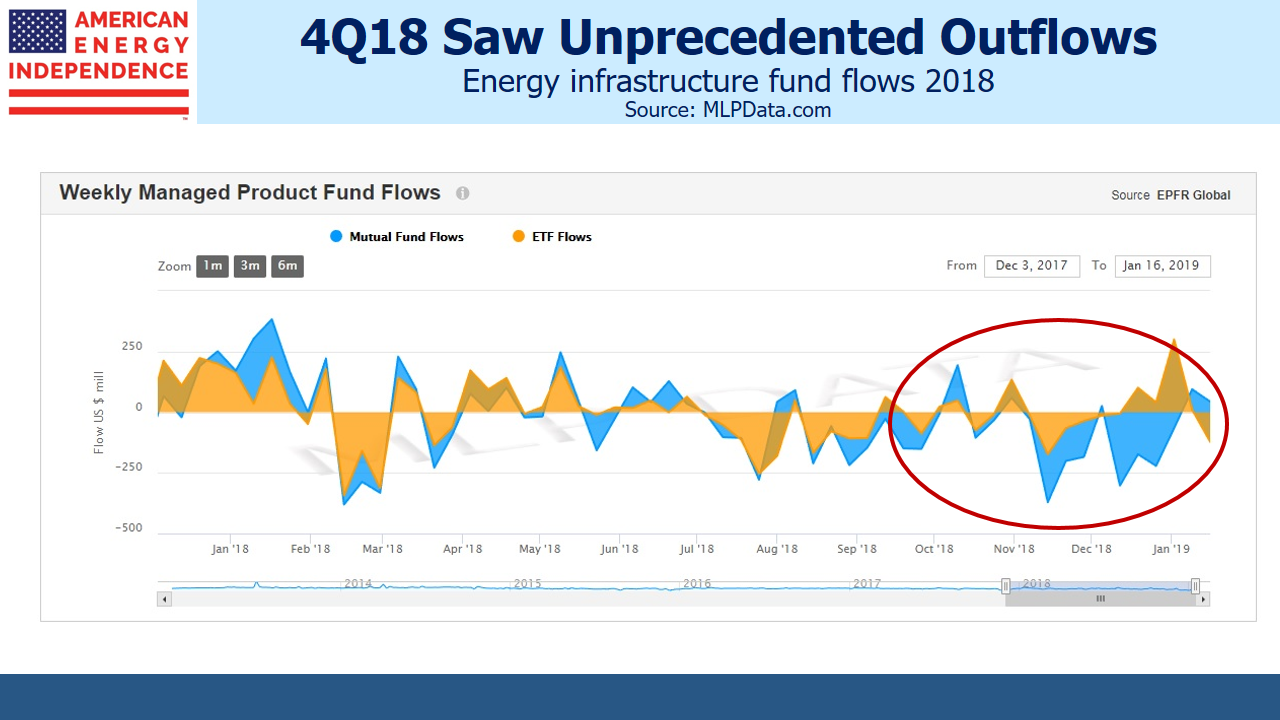

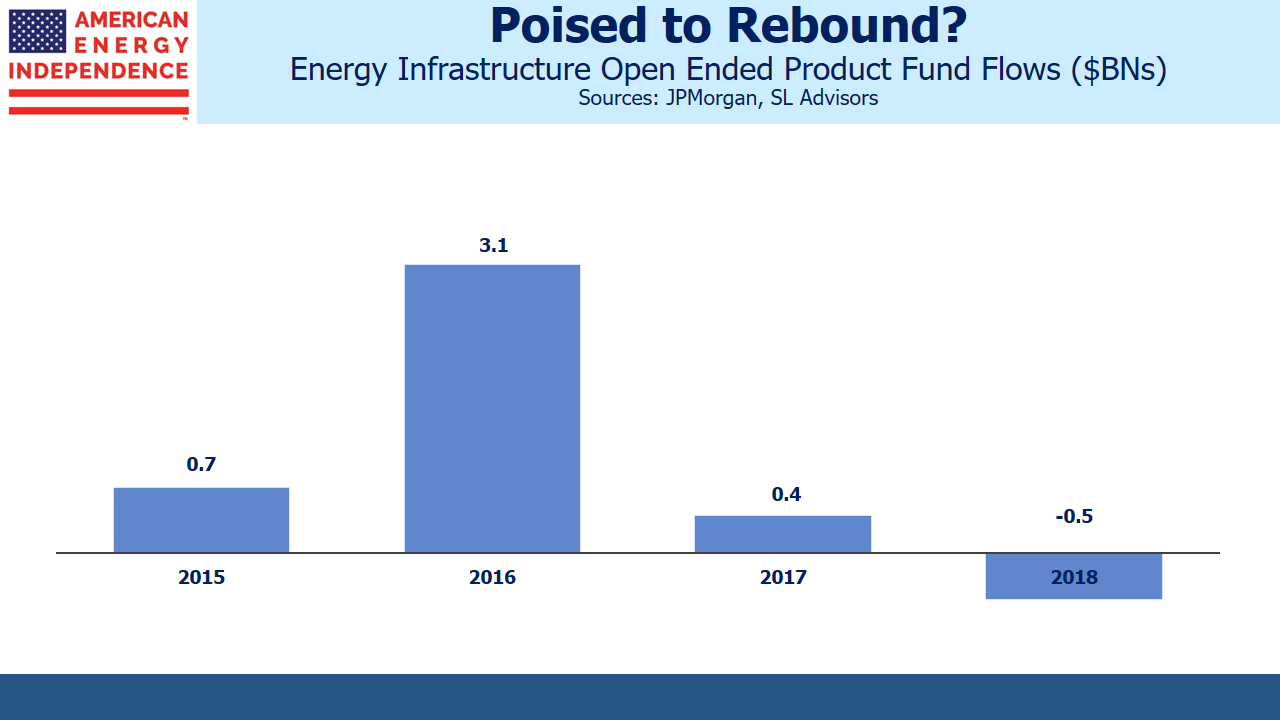

This is conjecture. It’s impossible to obtain hard data to support or refute this theory of market activity. So consider our perspective as a money manager in the energy infrastructure sector, in daily contact with clients and potential investors discussing the outlook. In December, callers were frustrated. The apparent disconnect between fundamentals and stock prices was confusing, troubling. What were they overlooking? What were we missing? Many held, but some didn’t. Frustrated at losses they couldn’t explain, having lost faith with repeated bullish analysis, the sector saw more outflows than inflows. Potential buyers noted compelling values, but usually were dissuaded by continued sector weakness. Unable to comprehend the inability of good financial performance to boost prices, many opted to wait. Tax loss selling towards the end of the year exacerbated.

The turn of the calendar coincided with a modest bounce in crude oil, as reports surfaced that the Saudis were sharply reducing crude exports to the U.S. Current prices are creating for them a substantial fiscal gap.

Conversations with clients and prospects have completely turned. Now callers want to know if there will be a pullback. Is the rally for real? Flows have also reversed. One day last week inflows to one of our funds outweighed outflows by 100:1. In December there were no buyers. In early January there are no sellers.

I was prompted to consider events in this light by a recent article in the Financial Times (Volatility: how ‘algos’ changed the rhythm of the market). Philosophically, I’m inclined to believe that automated trading simply does what humans do, just better and more cheaply. However, there is a less benign feature in that algos are also exploiting the inefficiences of humans. Michael Lewis showed this in Flash Boys by examining how high frequency trading systems will see market orders placed and race to snatch the best price before the limit order is executed. This happens in fractions of a second. But humans can also be outwitted over longer periods. December saw the biggest ever monthly outflows from mutual funds, capping an unusual year in which almost every market was down.

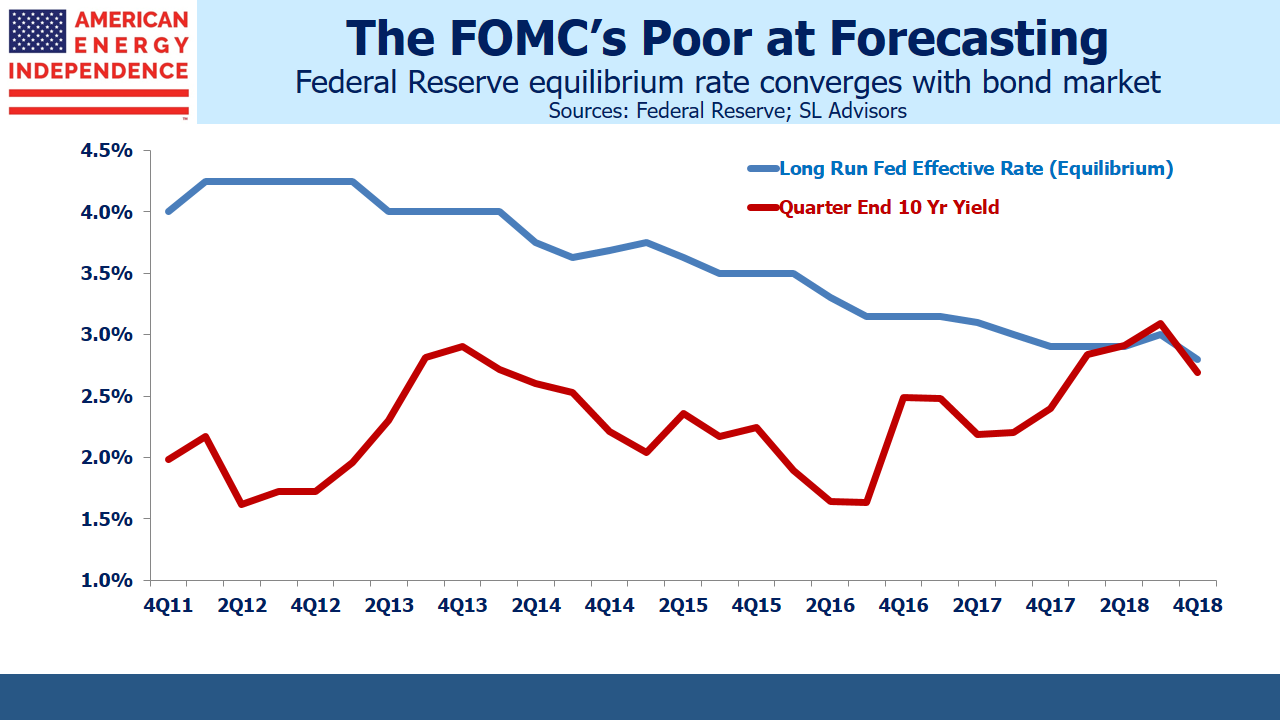

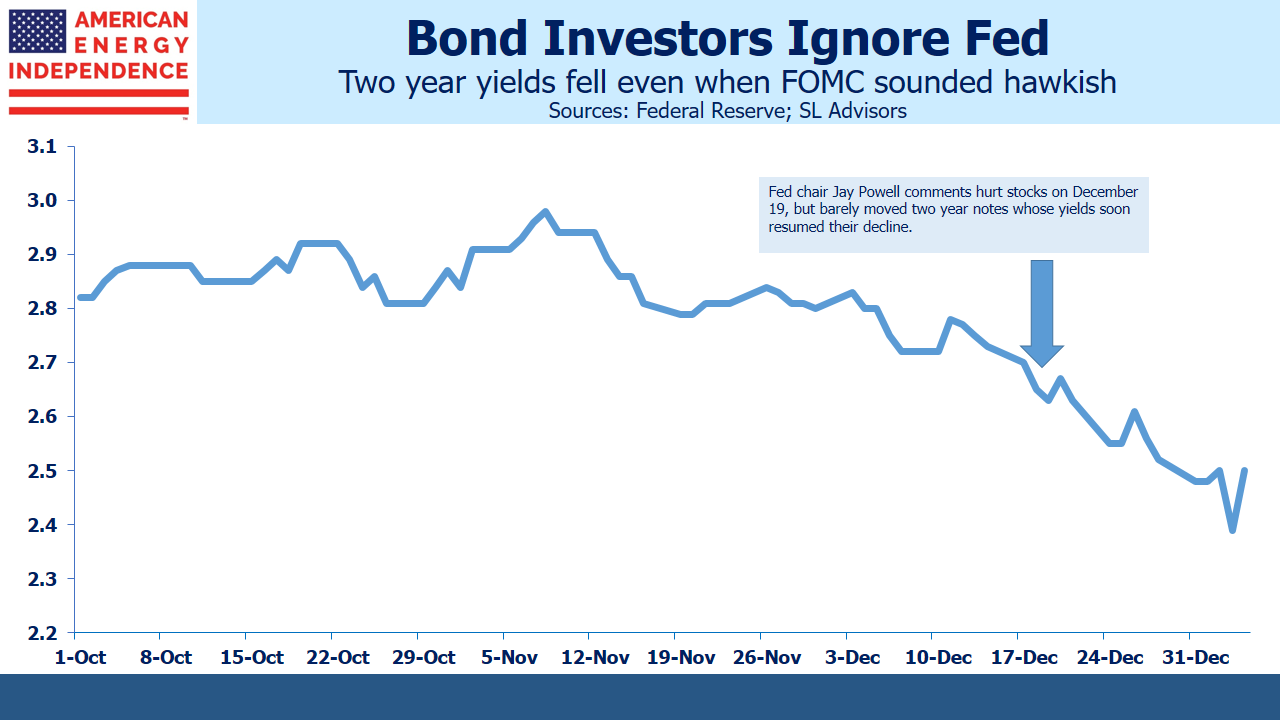

There was some bad news. The trade dispute with China is slowing growth there, and S&P500 earnings forecasts are being revised lower. The government is shut down. Fed chairman Powell sounded more hawkish before walking back his comments (see Bond Market Looks Past Fed). But these developments scarcely seem to justify record mutual fund outflows. There have been far worse environments for stocks.

Hedge fund veteran Stanley Druckenmiller said, “These ‘algos’ have taken all the rhythm out of the market, and have become extremely confusing to me.” Philip Jabre closed his eponymous hedge fund, complaining, “…the market itself is becoming more difficult to anticipate as traditional participants are imperceptibly replaced by computerized models.”

The Financial Times quoted a senior JPMorgan strategist as saying that, “…we just have to accept that equity markets are almost fully automated.” JPMorgan estimates that only 10% of trading is generated by humans.

The Wall Street Journal reported that trend-following trading systems shifted “…from bullish to bearish to a degree not seen in a decade, according to an analysis of algorithms that buy or sell based on asset-price momentum.”

The WSJ also blamed volatility in commodity markets on computerized trading, citing a report that “…Goldman Sachs attributed the recent volatility to algorithmic traders exerting more influence in the oil market.”

The growth in algorithmic trading seems to be coinciding with a drop in discretionary trading by humans, which probably reflects that computers are beating humans in certain areas.

On one level, algos are designed to exploit human frailties by anticipating them. Perhaps they even cause them. It seems many people had little reason to sell in December beyond fear of losing money. Successful algos by definition attract capital, increasing their ability to move markets and hunt for more inefficiencies. Humans, at least those who adjust their positions too frequently, are becoming prey. One result could have been systematic shorting of pipeline stocks in response to crude’s sharp drop, because it worked in 2014-15. Sector weakness certainly couldn’t be traced back to recent earnings reports. Investors who sold during this time because they tired of losing money added to the downward pressure, reinforcing the trend. This would also have provided confirmation to the algorithms that the signal worked.

Since computerized trading isn’t going away, survival for the rest of us lies in being less sensitive to market moves. Examining fundamentals and staying with a carefully considered strategy that doesn’t rely on the market for constant confirmation of its correctness is the human response to algos.

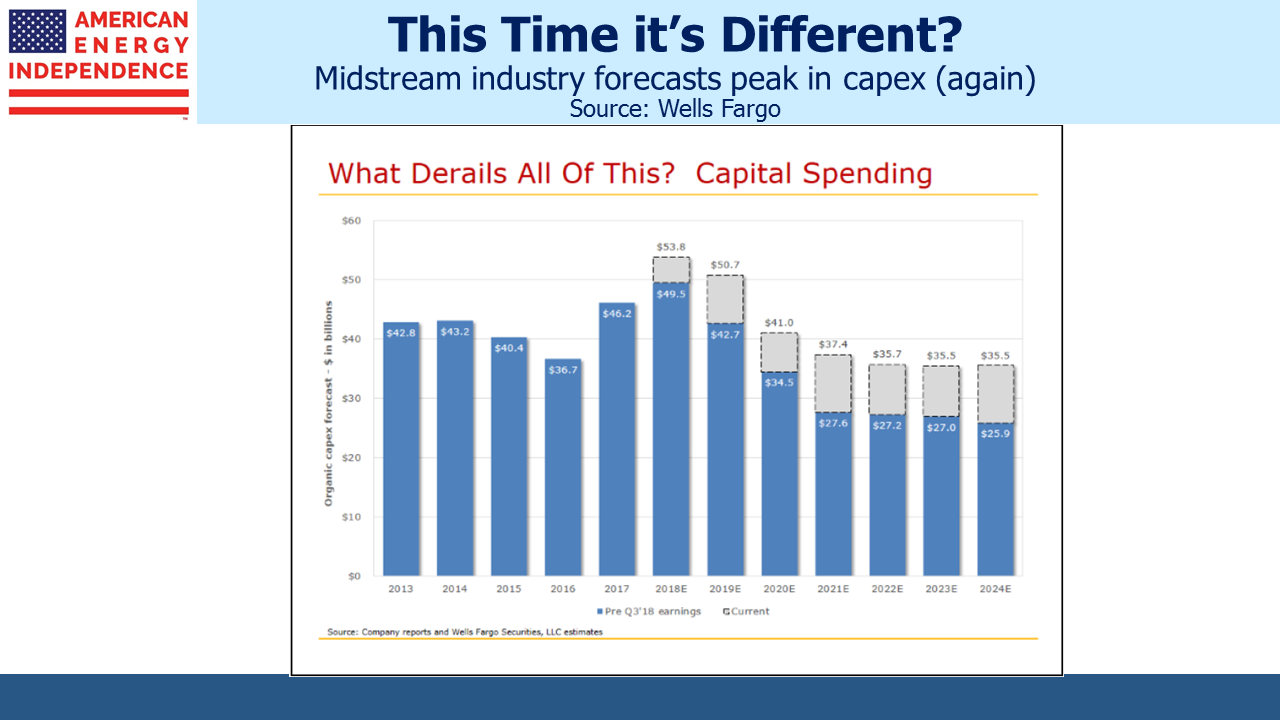

Energy infrastructure remains attractively valued. Free cash flow yields before growth capex (i.e. Distributable Cash Flow) are over 11%. We estimate dividends will grow on the broadly based American Energy Independence Index this year by mid to high single digits. The long term outlook for the sector remains very good.

We are short AMLP.

SL Advisors is the sub-advisor to the Catalyst MLP & Infrastructure Fund. To learn more about the Fund, please click here.

SL Advisors is also the advisor to an ETF (USAIETF.com).