Natural Gas Prices Rise for Democrats

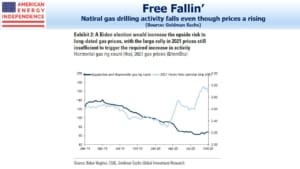

In recent weeks, 2021 natural gas have been quietly moving higher. November ’21 futures have rallied over 40 cents, to just under $3 per Thousand Cubic Feet (MCF).

Covid and the election are both behind this. Research reports from Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley both explore energy markets through the pandemic and likely policy changes if Democrats win next month.

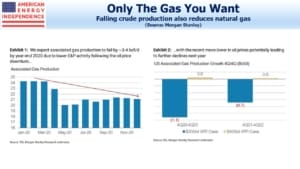

Associated gas that is produced along with crude oil in the Permian in west Texas has long weighed on prices. This gas wasn’t needed – because it had so little value, some of it was flared. The Texas Rail Road Commission (RRC) never rejected a flaring application, causing critics to ask why they regulated it at all (watch Stop Flaring).

The collapse in oil demand in the Spring led to production cutbacks in the Permian, which also reduced the volume of associated gas. Morgan Stanley notes that falling prices had already been reducing the gas rig count in key producing areas prior to Covid, and this trend accelerated during the spring. Domestic gas production is increasingly driven by the economics of the gas market.

The election has had a more recent impact. With Joe Biden retaining his lead in opinion polls, markets are beginning to price in a Democrat victory, including the possibility of taking control of the Senate. VP candidate Kamala Harris pledged that a Biden administration would not ban fracking – a predictable pivot away from the anti-fracking posture Biden adopted during the primary.

Some of the more sweeping moves against the domestic energy business associated with the Democrat platform would require acts of Congress. This includes banning fracking on private land. Another example would be tightening the standards around produced water, since the 2005 Energy Policy Act excluded fracking from the Safe Drinking Water Act. It’ll be hard persuading senators from either party in oil-producing states to support legislation that’s harmful to their voters.

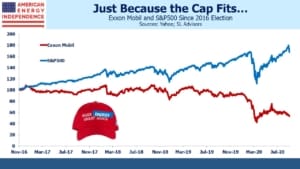

However, Goldman notes that a Biden presidency could restrict drilling on Federal land, clamp down on methane emissions and use other regulatory tools to increase the cost of production. Democrat policies are designed to produce higher energy prices, since this improves the competitiveness of renewables (Listen to Joe Biden and Energy and read Why Exxon Mobil Investors Might Like Biden).

A new administration might also engage more with Iran. Goldman notes that the return of 1 million barrels per day or Iranian output to oil markets would restrain Permian crude production and keep a lid on associated gas. It’s not intuitive, but diplomatic engagement with Iran is bullish for natural gas prices.

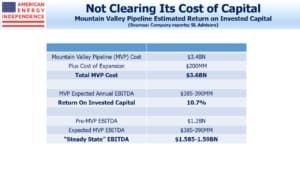

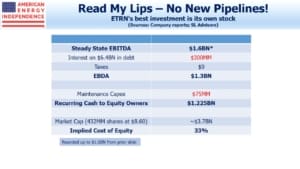

Will this be good for pipeline stocks? Trump pursuit of energy-friendly policies has led the industry into an exuberant glut of production. It’s not his fault, but it’s led to poor investment returns. Rising natural gas prices could be a sign of more parsimonious capital allocation. If pipeline stocks follow energy prices up the same way they’ve followed them down, few investors will complain.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.