Still Fearing Another Financial Crisis

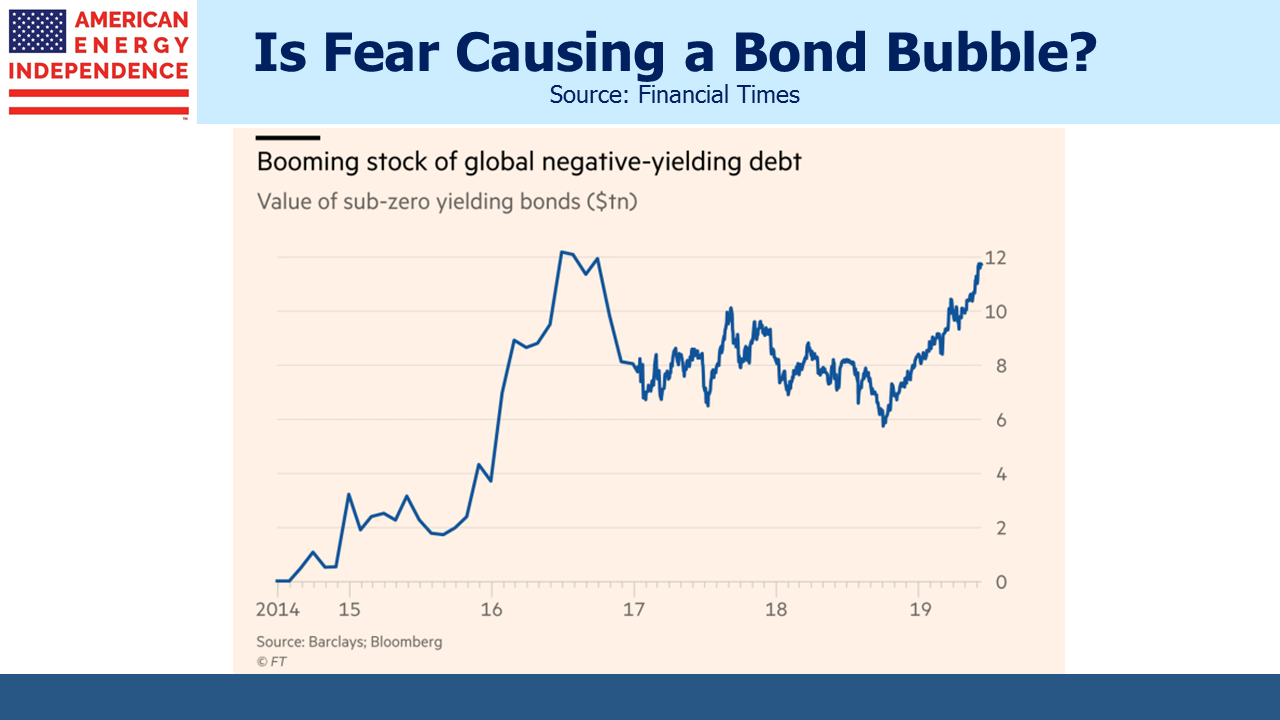

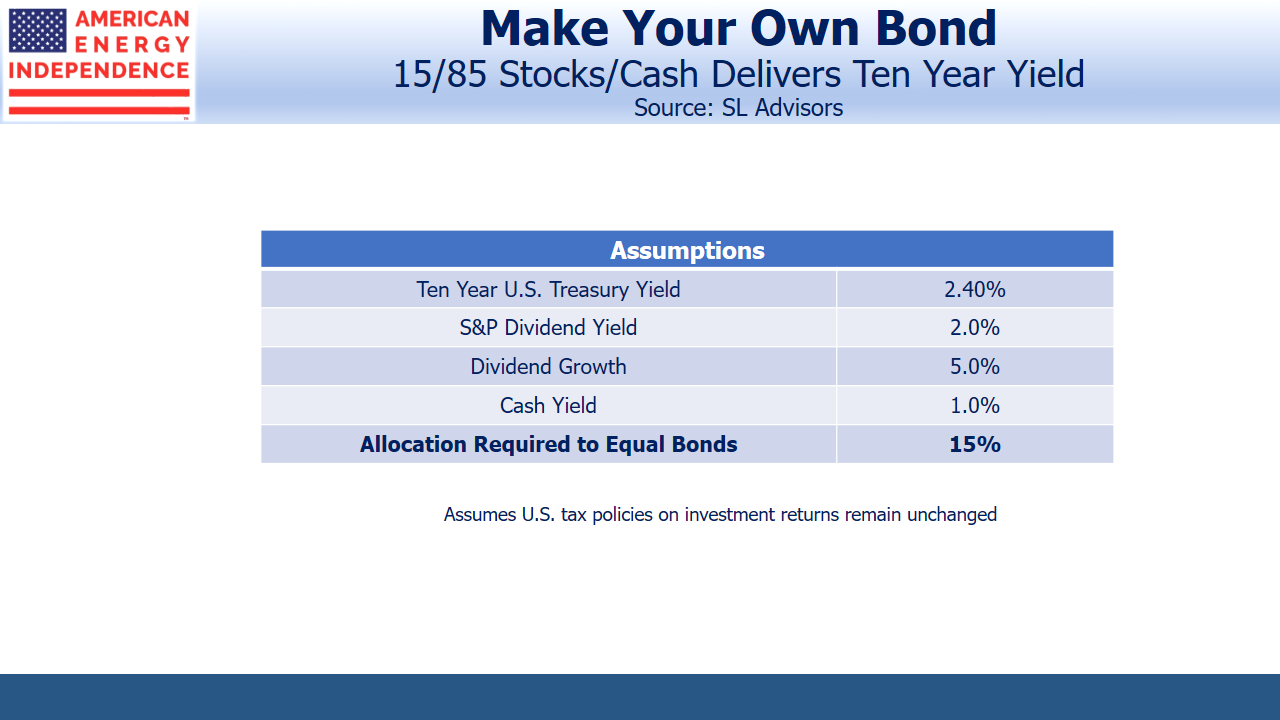

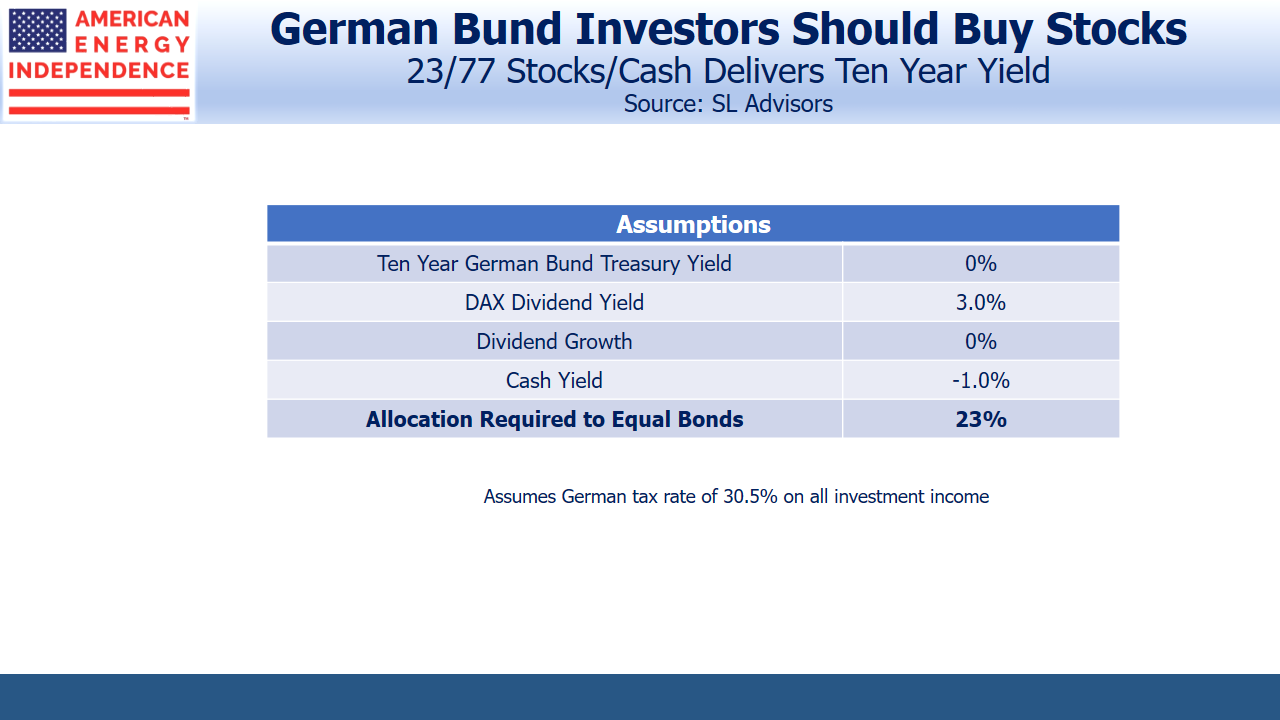

“Concerns about trade and Gulf tensions spur rush towards sovereign debt.” warned the Financial Times last week. Almost $12 trillion in bonds trades at a negative yield. According to Tim Winstone, fixed income portfolio manager at Janus Henderson, “Investment grade is nuts. About 24% of my benchmark yields less than zero.” Even a dozen European junk bond issues trade with negative yields.

The comments by Tim Winstone reveal much about investor risk appetites today. As a fixed income manager, his job is to pick bonds and stay invested. His clients have already made their asset allocation choice. While he might rationally choose to shun junk bonds in favor of equities, which at least have the potential of a positive return, his mandate doesn’t offer such flexibility.

Colin Purdy, Chief Investment Officer at Aviva Investors, explained, “For some investors, there is an acceptance that it’s not about absolute returns, but relative returns.” This is true to a point, but most investors would add that positive nominal returns are a priority.

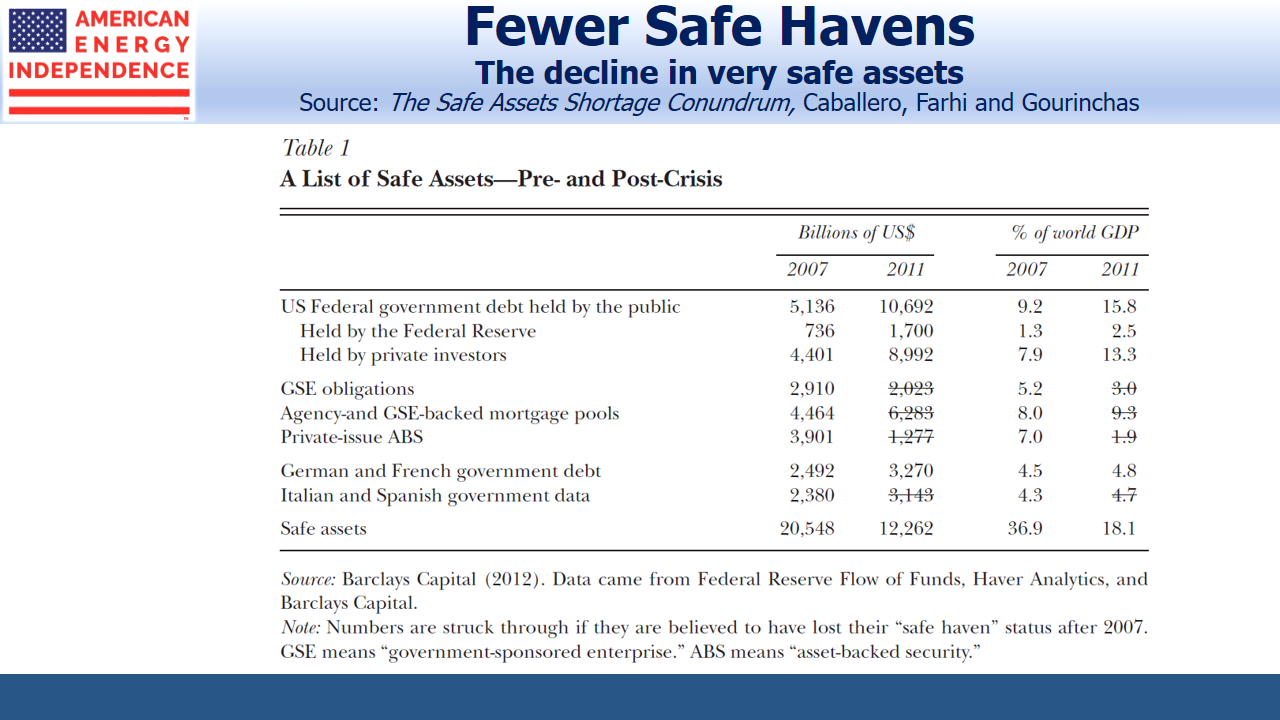

Firms that invest in bonds for clients are grappling with an excess of demand versus supply. Rigid fixed income allocations that are insensitive to return reflect extreme risk aversion.

Market participants are drawing different conclusions from this. A common misconception is that bonds reflect looming trouble for stocks. Someone once explained to me that bond buyers are naturally a dour bunch because we just want our money back, while equity buyers can dream of unlimited upside. But just because fixed income investors look more closely at balance sheets doesn’t mean that they’re always right.

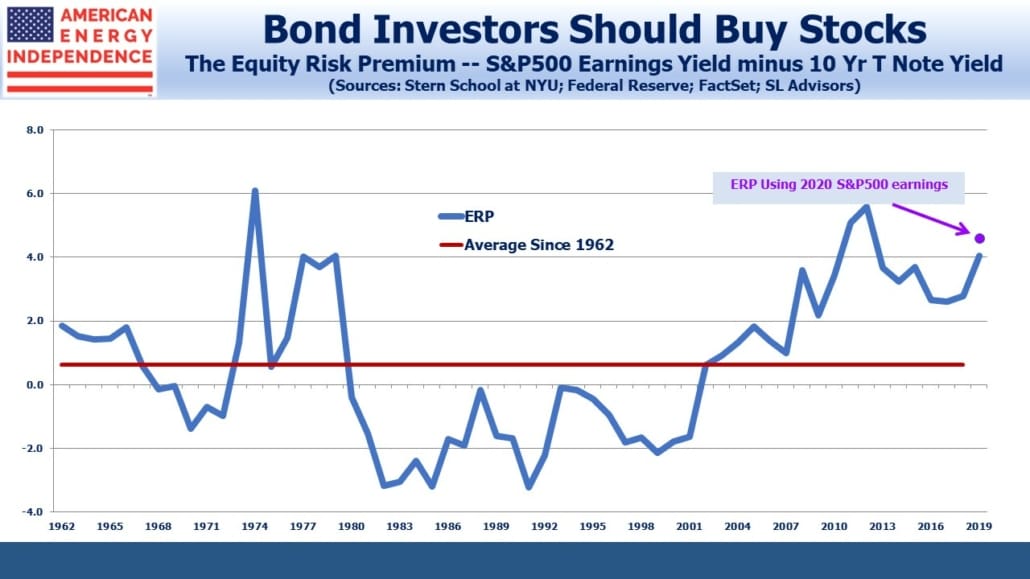

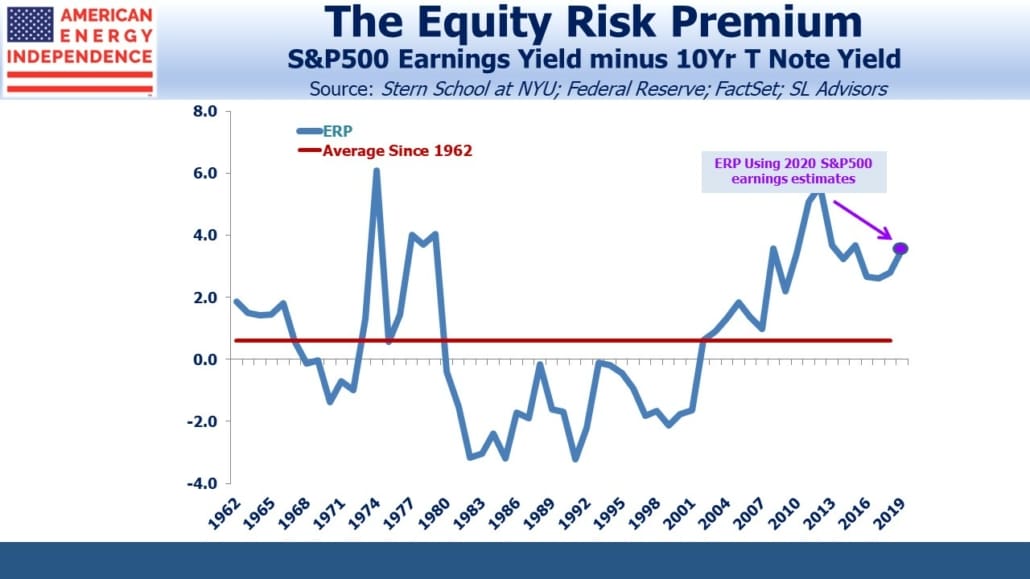

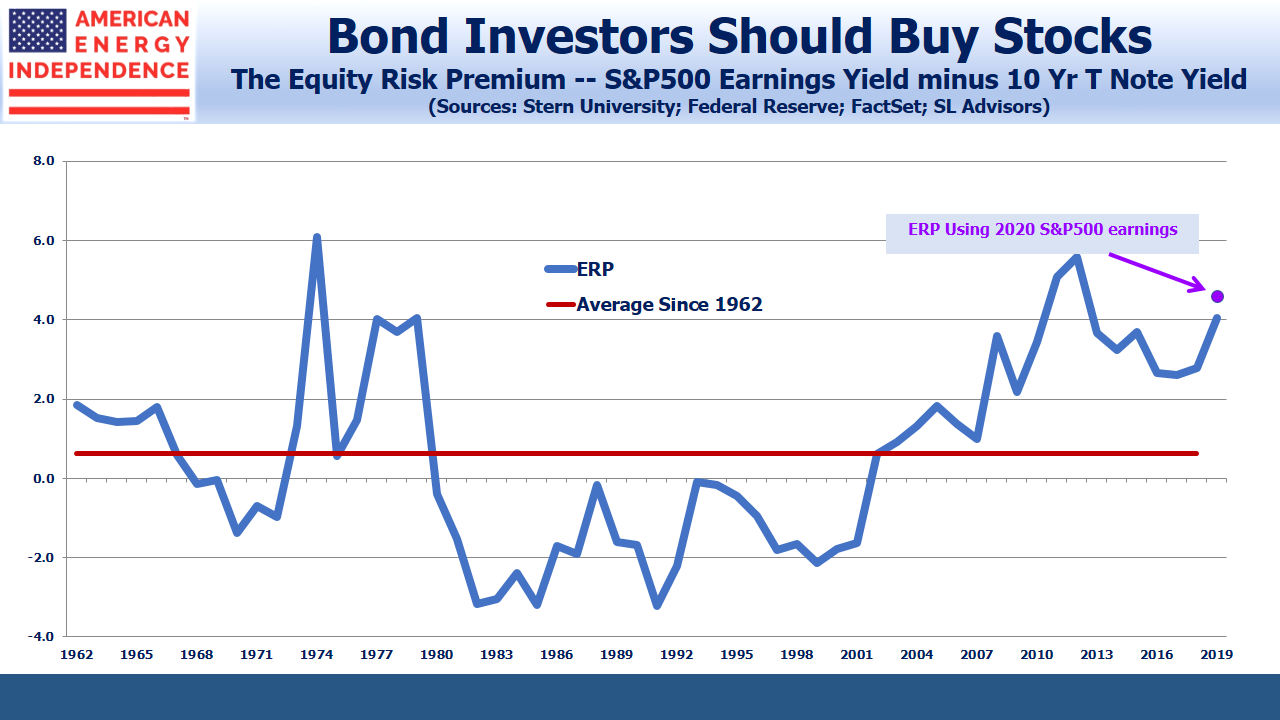

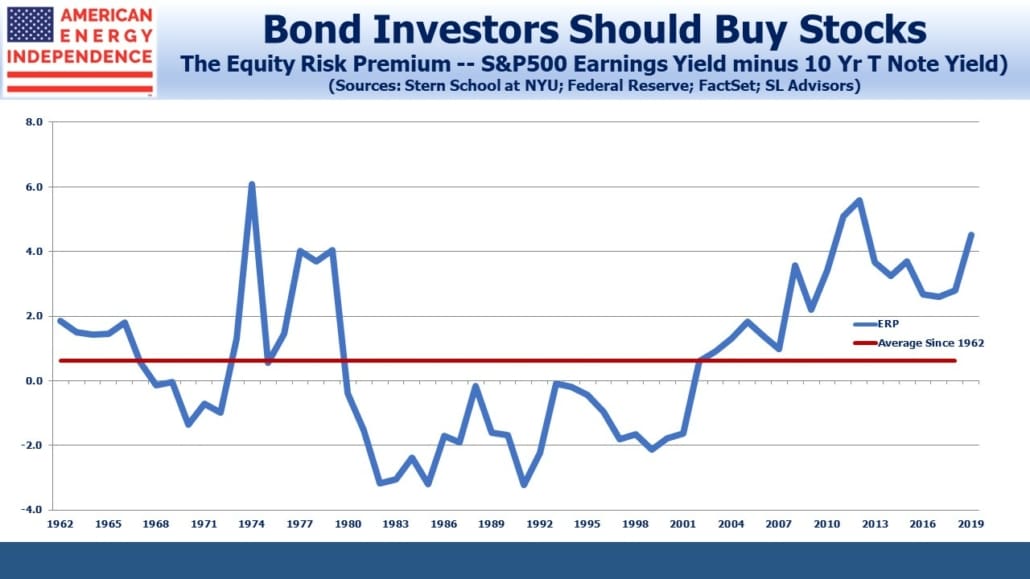

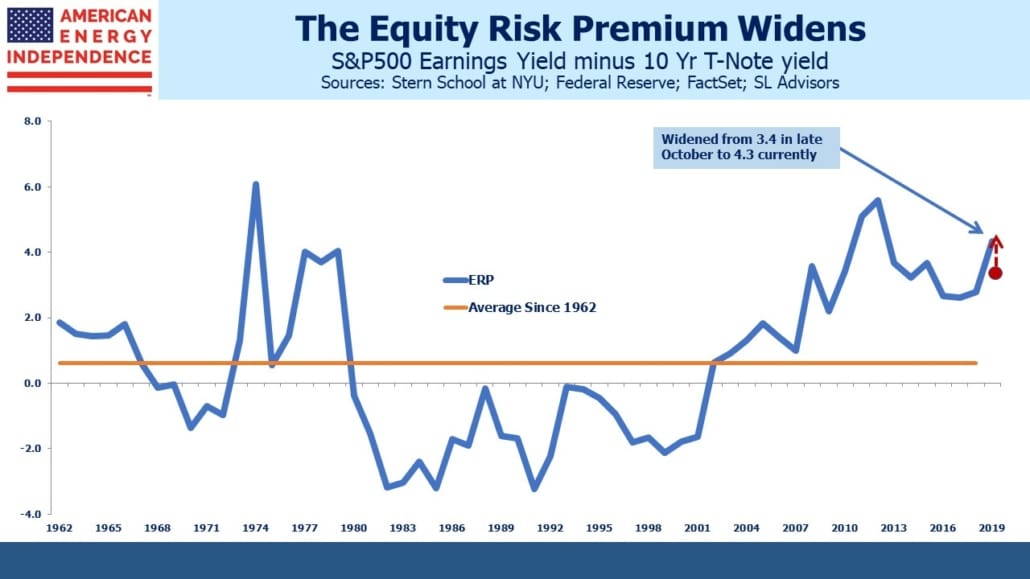

If yields reflect extreme risk aversion, so do P/Es. While there’s no shortage of observers warning that stocks are over-priced, a lot of money that could buy equities is scared, preferring to own negative-yielding bonds instead. The conclusion must be that fear of another financial crisis runs wide and deep.

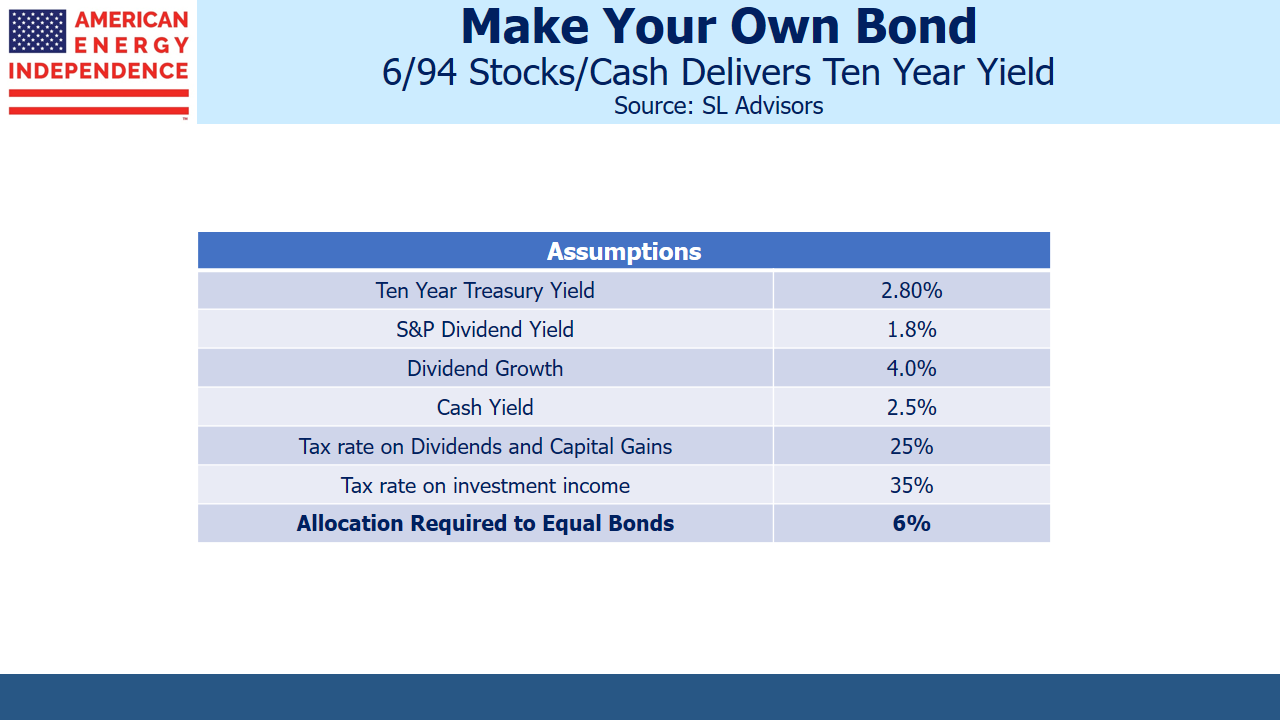

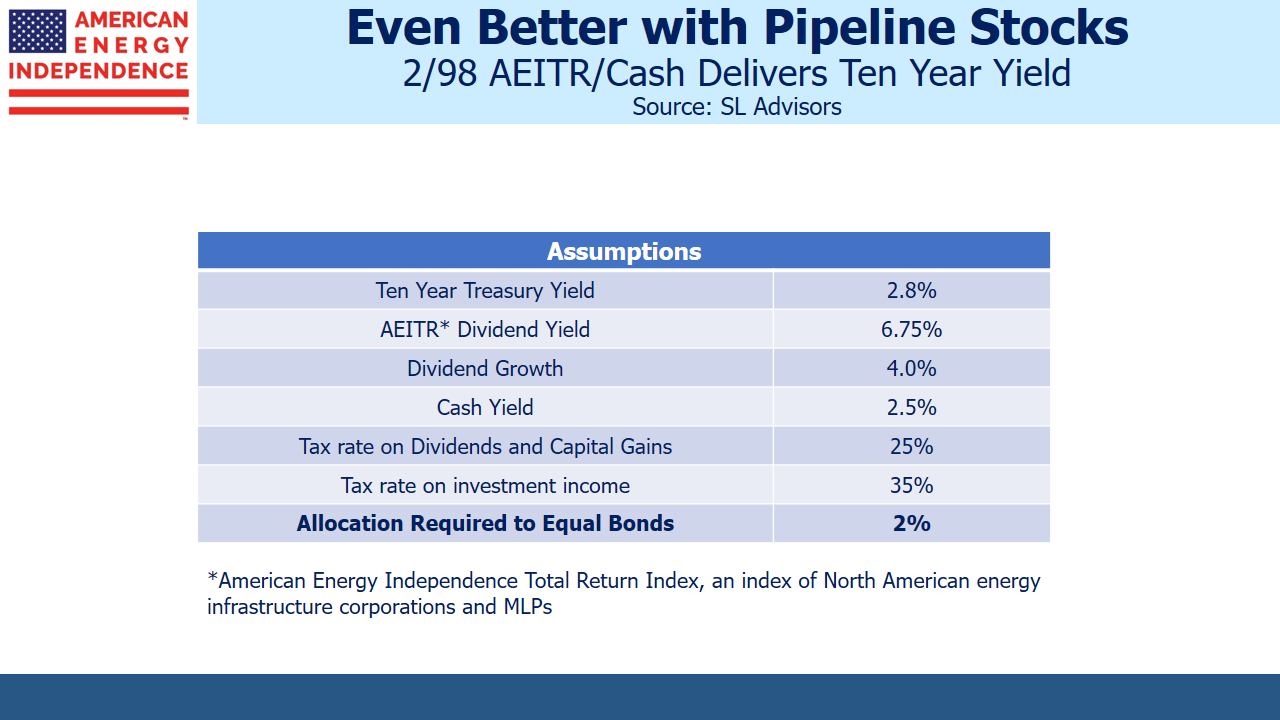

Infrastructure offers the stability of bonds with the upside of equities. This is especially true of midstream energy infrastructure (see The Coming Pipeline Cash Gusher). Valuations reflect the expectation of equity volatility with bond-like returns, but every quarter balance sheets strengthen, cash flows increase. Current holders are benefiting.

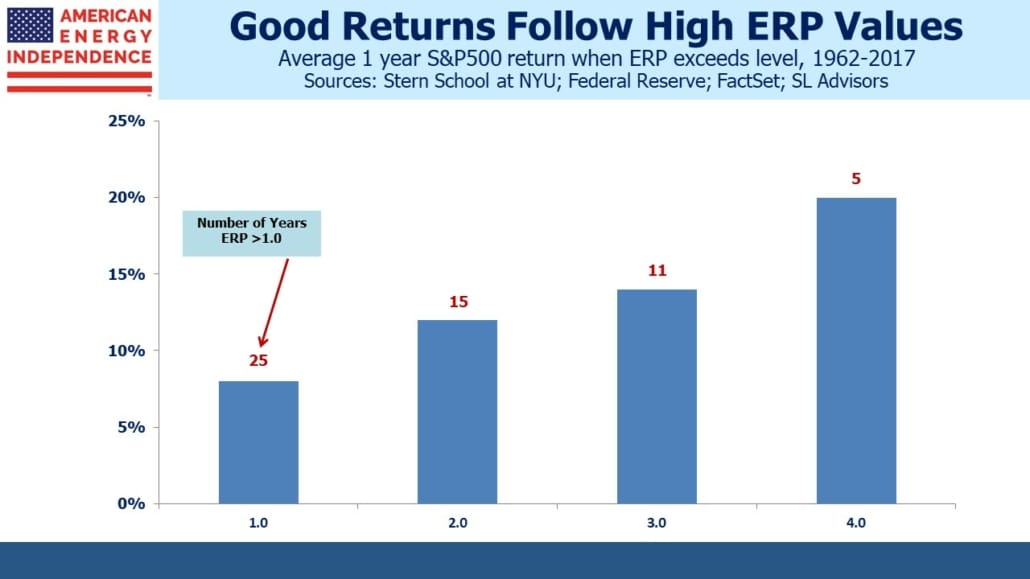

Last week, in Real Returns On Bonds Are Gone, we showed how much equities could appreciate before becoming historically expensive versus bonds. The quotes above from fixed income managers reflect widespread institutional risk aversion. At some level you might think firms would turn money away rather than invest it for negative returns. But they don’t, and it therefore falls to clients to impose more discriminating criteria.

What seems clear is that if stocks fall 25%, many investors will be comfortably positioned in fixed income. Their equity exposure was already set for that possibility.

But if none of the bad things people fear happen, and bonds fall, poor returns will be exacerbated by negative starting yields. The stock market continues to climb the wall of worry. Surprises will cause a drop, but the plausible negative events are priced in.

SL Advisors is the sub-advisor to the Catalyst MLP & Infrastructure Fund. To learn more about the Fund, please click here.

SL Advisors is also the advisor to an ETF (USAIETF.com).