Pipeline Earnings Offer Helpful Insights

Earnings season for pipeline companies is drawing to a close, with just a few more names left to report. Results have been mostly as expected with a couple of surprises. Targa Resources (TRGP) handily beat expectations for 4Q19 EBITDA at $465MM versus $362MM. CEO Joe Bob Perkins drew criticism last year for his flippant comment about “capital blessings” when responding to investor questions about growth capex. A charitable assessment of TRGP’s capital allocation would concede that they embrace investing for future cashflow more than most of their peers. However, it does look as if they’re in the middle of a big swing in Free Cash Flow (FCF) 2019-2021. Following earnings, TRGP jumped 7%.

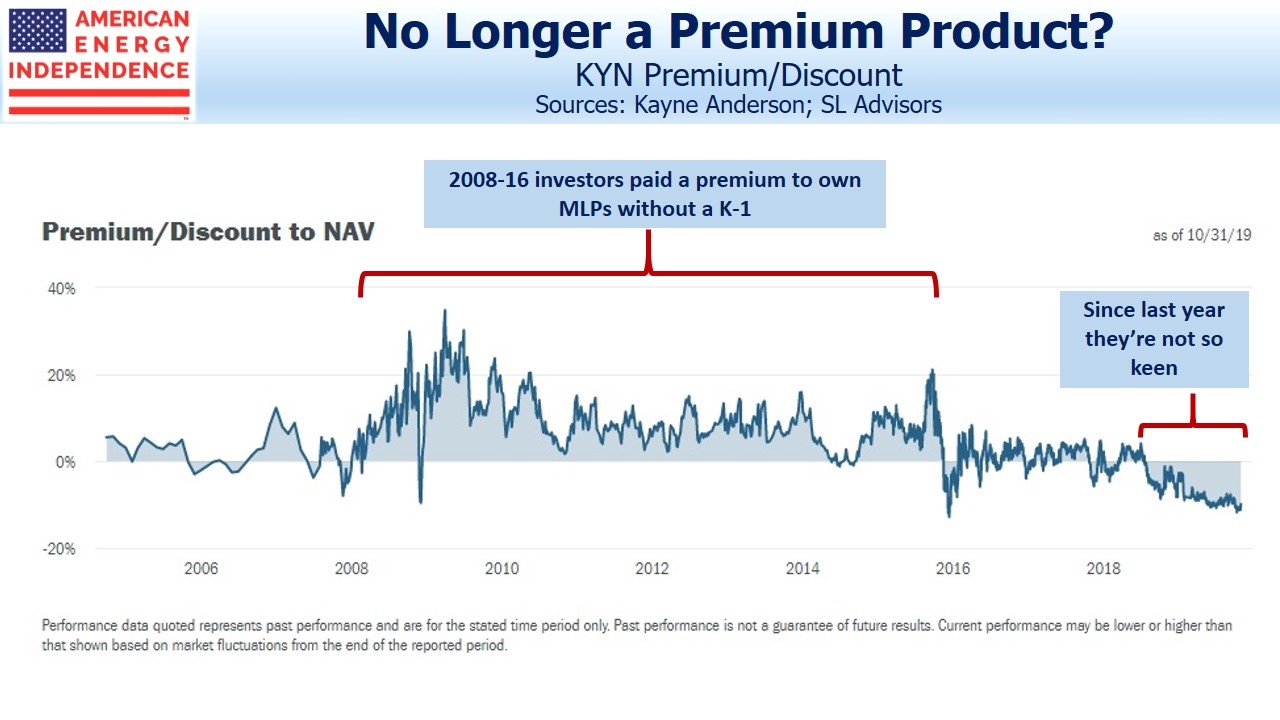

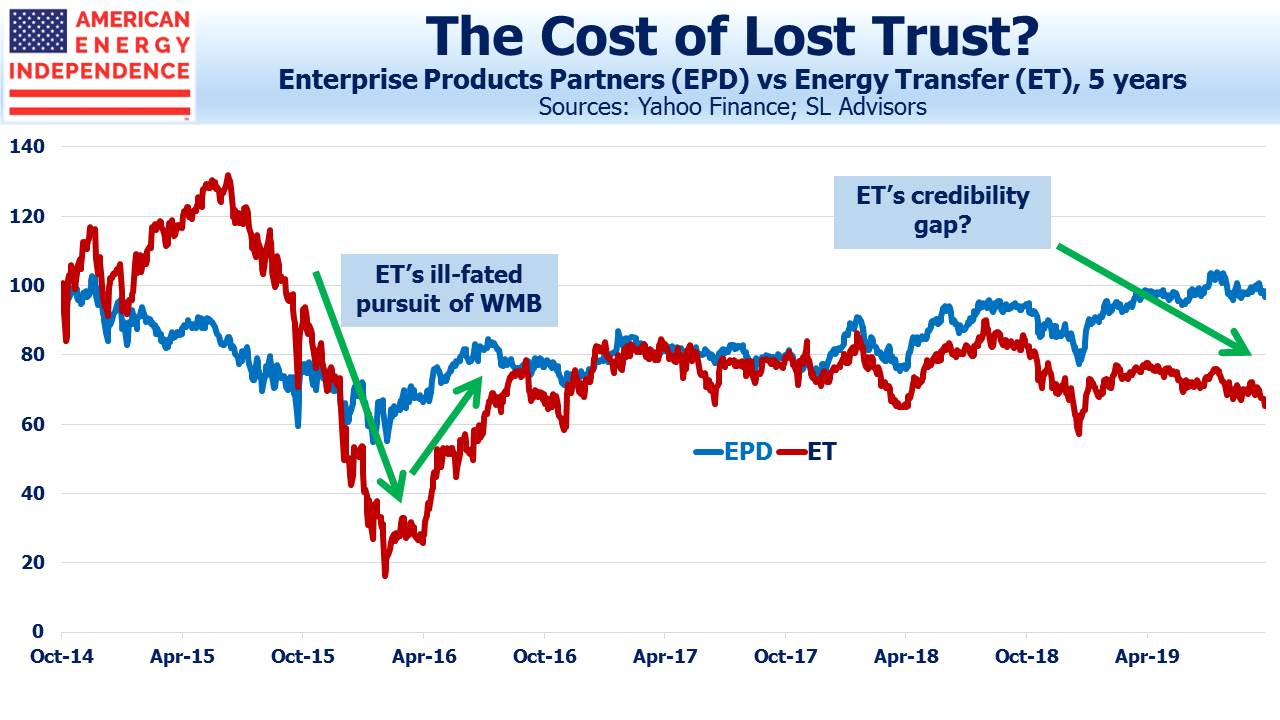

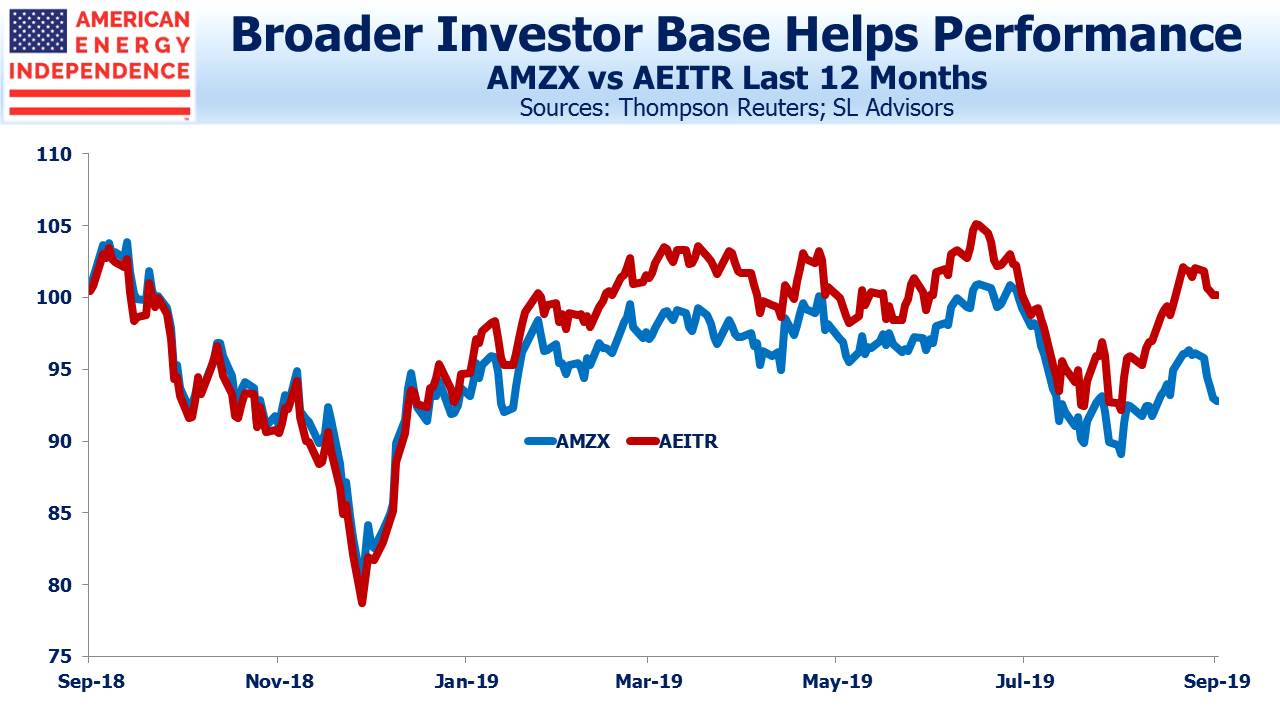

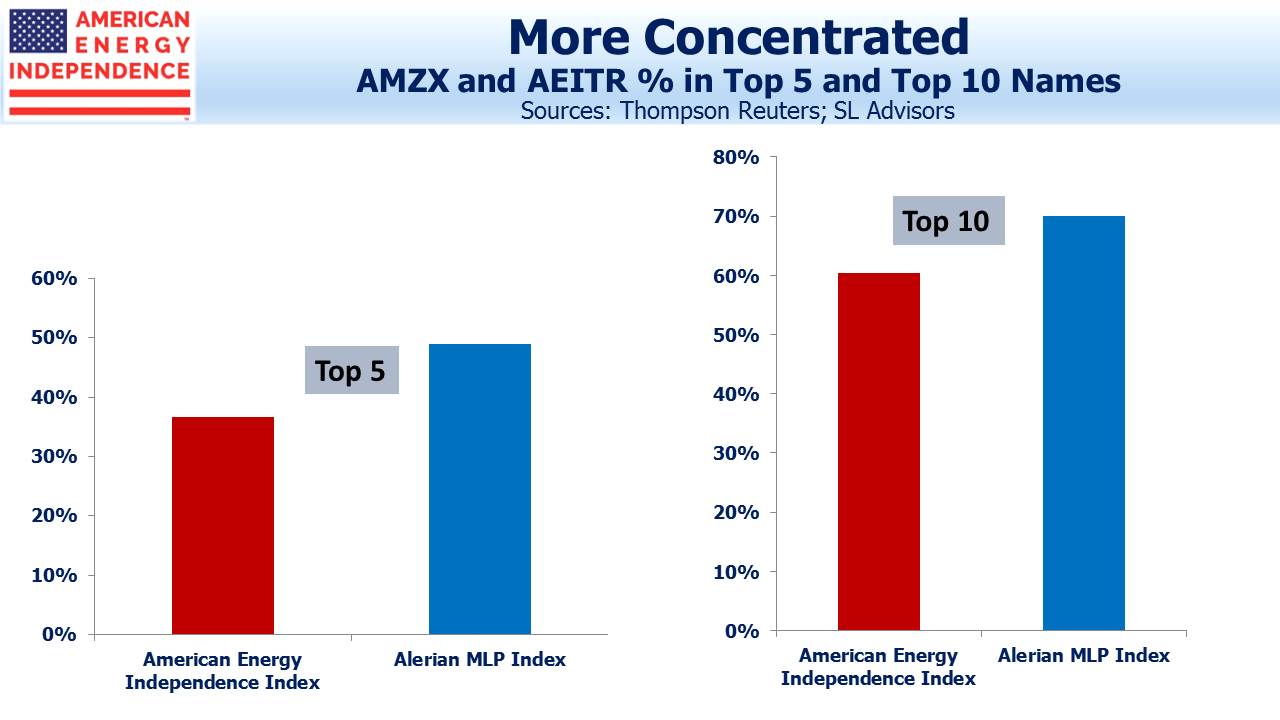

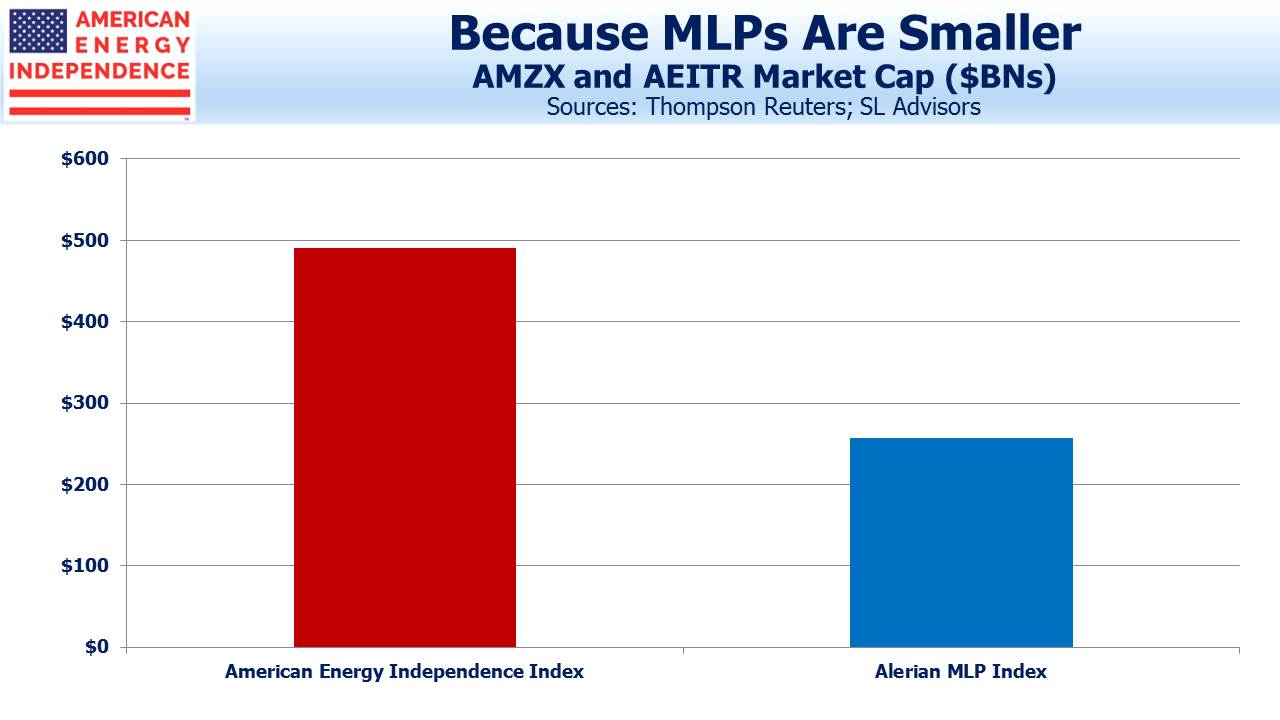

Energy Transfer (ET) reported another strong quarter and guided long term growth capex down to $2.0-2.5BN. 2018 FCF was ($412MM), and this year it should come in above $2.5BN, illustrating the very positive FCF improvement across most of the industry as financing of growth projects recedes. ET was also ready for the predictable question on structure – a “c-corp option” was their response, presumably meaning they’ll create a 1099-issuing entity that holds ET units. This will broaden the investor base but leave whatever concerns investors have about governance unresolved – by offering investors a c-corp without traditional corporate governance, its price may shed some light on the valuation discount partnerships endure.

Williams Companies (WMB) reported in-line earnings, but the conference call offered some useful insights. Upstream companies (i.e. oil and gas producers) are the customers of midstream energy infrastructure, and E&P bankruptcies often cause concern that pipelines will be left stranded, running to wells that no longer produce. WMB CEO Alan Armstrong had this to say,

“After a very long time in this midstream business, I have seen and experienced many instance of producers’ stress and even bankruptcy, and it’s very clear to me that the most protected service by far is that a wellhead gathering. Wellhead gathering is absolutely essential to any reserves that are going to be produced. Gas could not get to market and cash flow cannot be realized, if wellhead gas gathering is not available.

“While counterparty credit is important, the physical nature of the service is even better security.”

History has shown that in general an E&P bankruptcy just leads to a change of ownership – initially often the bondholders as equity is wiped out. Where production covers operating costs but earns an inadequate return on capital, the drilling lease was purchased at too high a price with excessive debt. Bankruptcy alters the capital structure. Pipeline operators are generally kept whole.

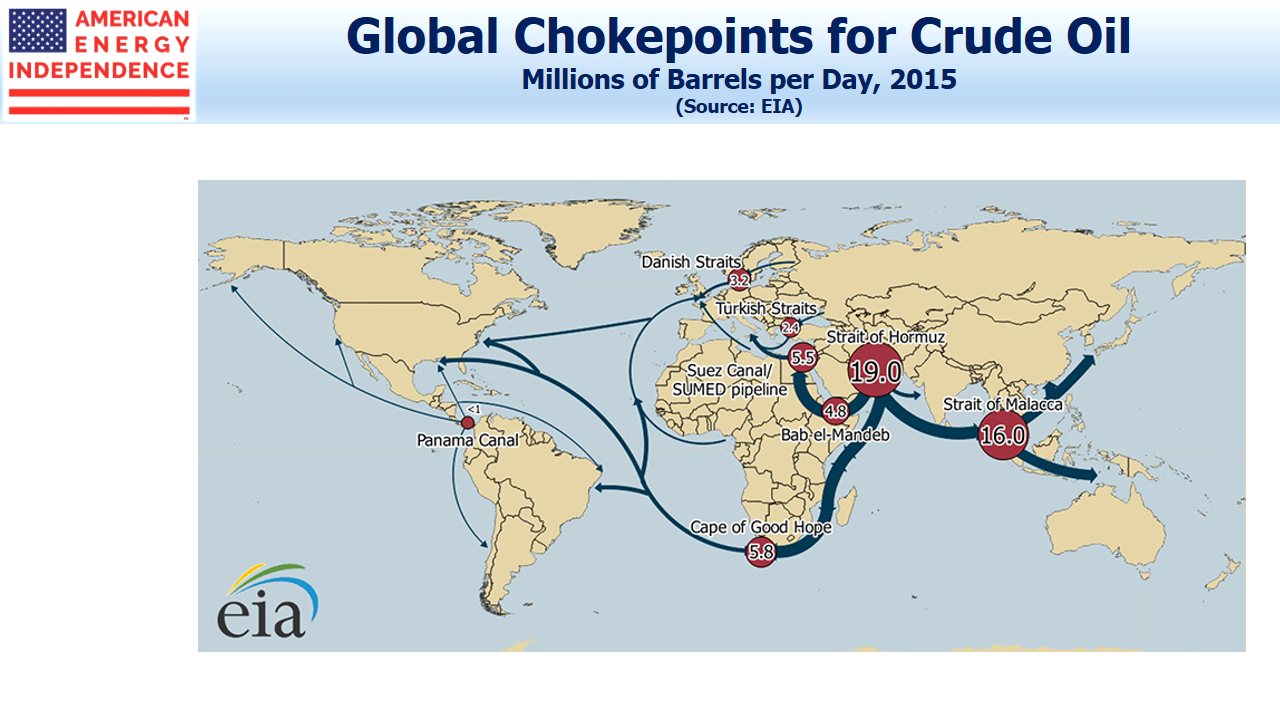

On another topic, opposition by environmental extremist to new pipeline construction represents an undemocratic effort to achieve what they’ve failed to democratically. For an investor interested in FCF, making pipelines harder to build lowers growth capex, leaving more cash to be returned to investors. So while pipeline opponents betray only a passing familiarity with how modern civilization functions, their wrongheaded moves aren’t necessarily unfriendly to investors.

Making new pipelines harder to build can also increase the value of existing ones. Alan Armstrong had this to say about Transco, WMB’s extensive natural gas pipeline network:

“The forces you see working in the market today are only increasing the competitive advantages of Transco. Low prices continue to incent demand in all sectors, and our access to many geographies and types of demand is unmatched. LNG, industrial, power, residential, commercial are all growing along Transco.

“Difficulties seen by Greenfield pipeline projects will also benefit Transco in the long run, as Transco has uniquely positioned to meet new capacity demand by expanding along its existing rights of way, which are irreplaceable and unmatched in terms of their proximity to demand.”

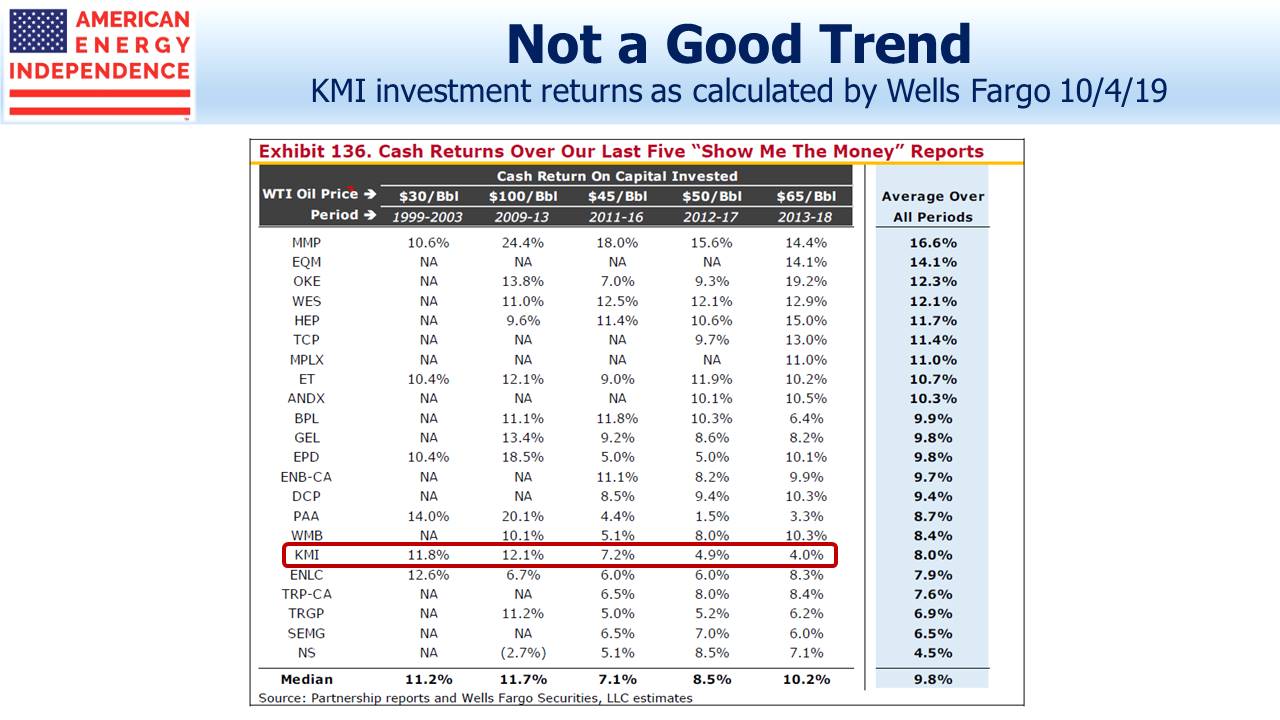

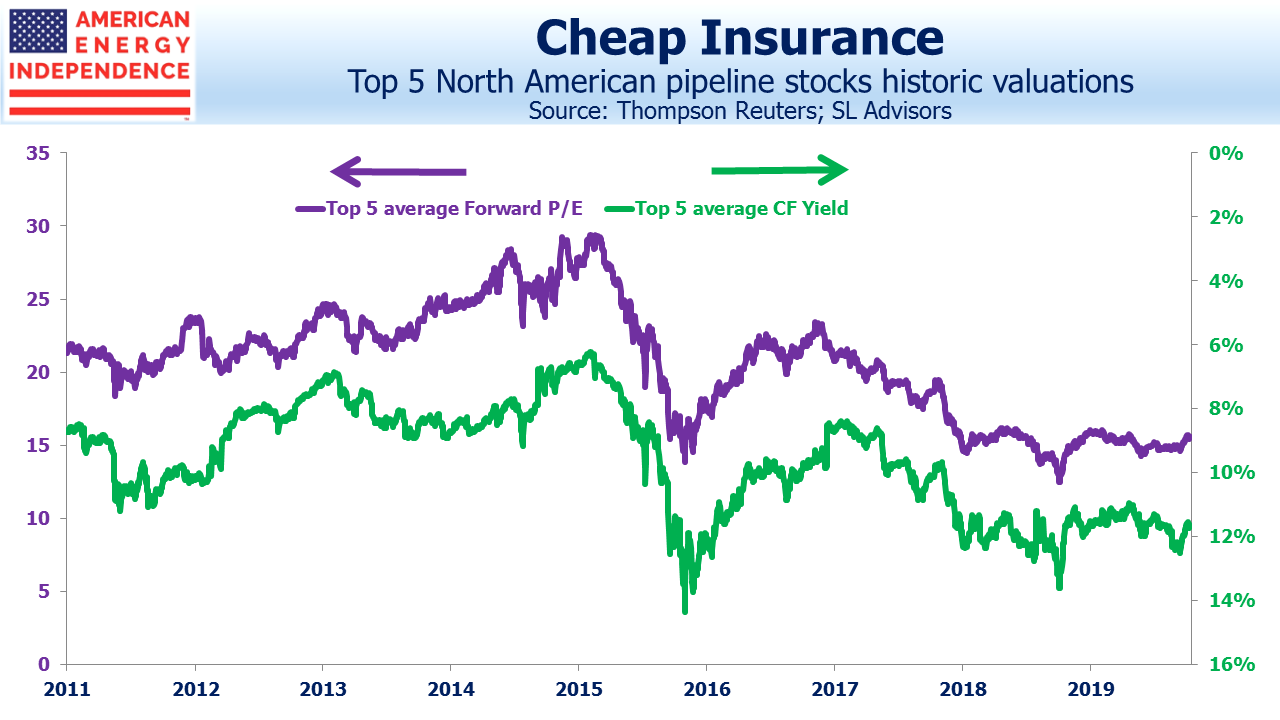

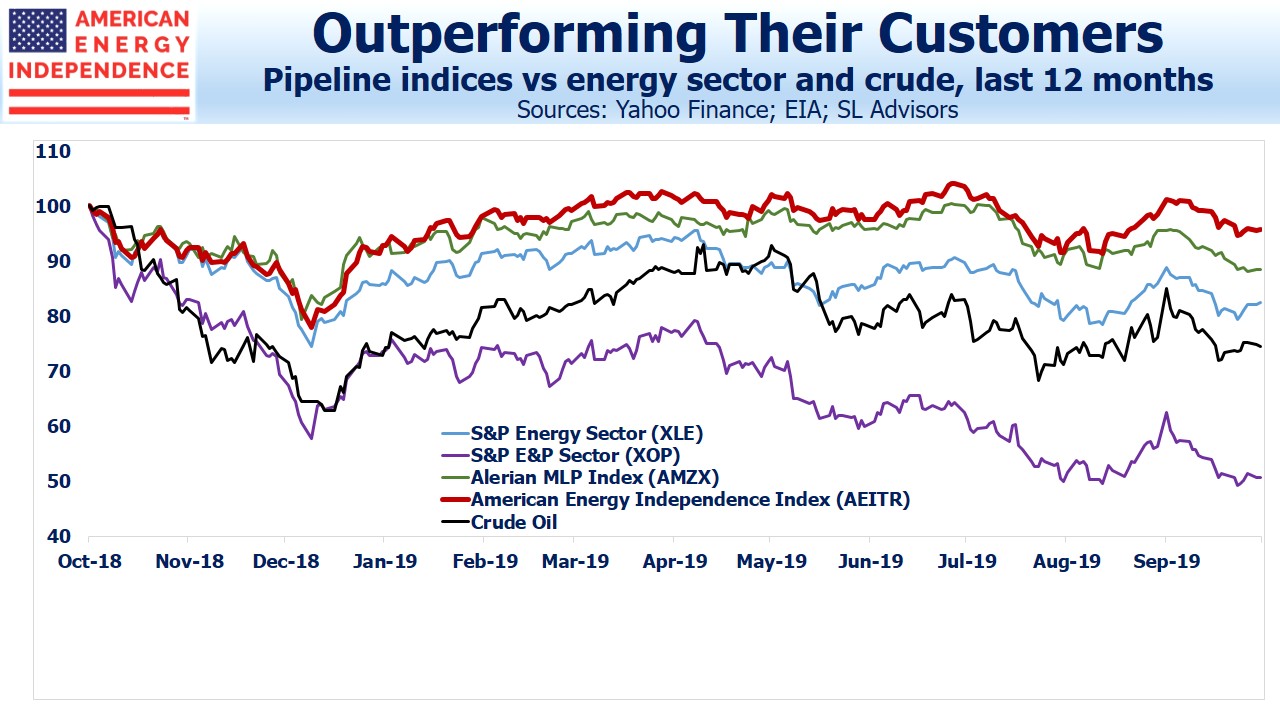

As we’ve mentioned in the past, growing FCF remains the strongest reason to invest in pipelines. Last year the two big Canadians, TC Energy (TRP) and Enbridge (ENB) were half the FCF of the sector as defined by the broad-based American Energy Independence Index. Consequently, TRP and ENB both outperformed the S&P500 in 2019, providing solid evidence that strong operating performance trumps any investor aversion to the energy sector.

This year the two Canadians’ share of FCF should drop if, as we expect, other companies finally start to emulate them.

We are invested in all of the names mentioned above.