Why Staying Warm In Boston Will Cost You

We spent last weekend in Boston with our daughter, who’s at school there and just turned 21. We visited the Mapparium, a glass spherical room that has the visitor standing inside the globe, with the world’s countries as in the 1930s (i.e. much of Africa was controlled by European powers and India had not yet gained independence from Britain).

It’s a cool experience. The Mapparium highlights features often not apparent on a 2D map – Greenland and Madagascar are approximately the same size; Britain is further north than Nova Scotia but enjoys a milder climate thanks to the Gulfstream; Russia sits at roughly the same latitudes as Canada; and Naples, FL is approximately on the same latitude as Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, even though the latter is often at least 20 degrees F hotter. Visiting the Mapparium, in the Mary Baker Eddy Museum, can be done in an hour or less and is worth the visit.

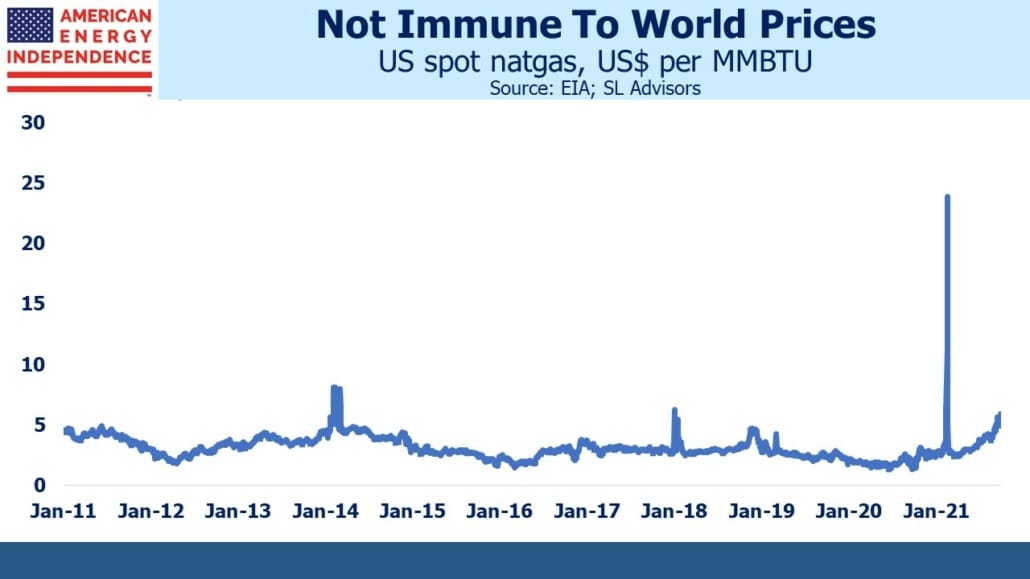

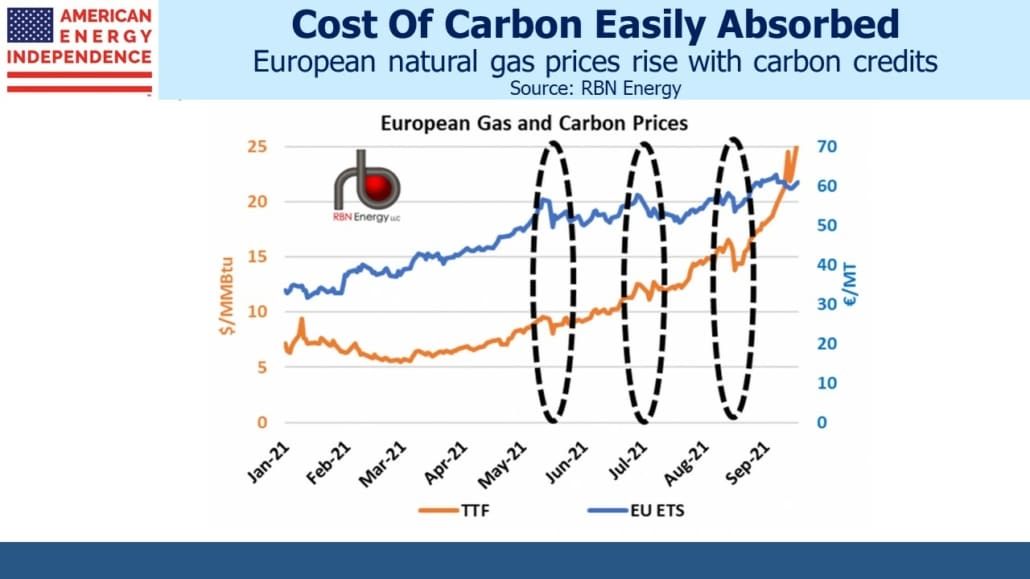

Visiting New England reminded me of the region’s dysfunctional energy policies. Unwilling to allow natural gas to be transported by pipeline from the Marcellus shale in Pennsylvania, Boston has in the past relied on imported Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) from Russia. The US has been mostly spared the impact of the energy crisis engulfing Europe and Asia.

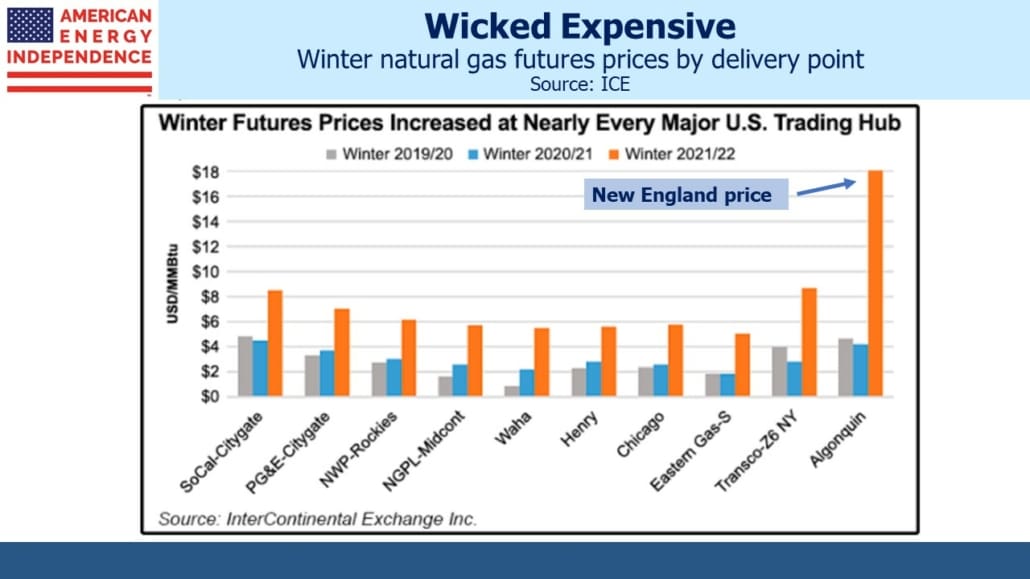

This winter that will change as high natural gas prices increase the cost of heating homes and businesses. New Englanders will feel it more acutely than most based on futures prices.

Favoring imports from our geopolitical rival rather than Pennsylvania means they’ll soon be following LNG prices in Europe and Asia, since that’s who they’ll be competing with to stay warm.

Once again, energy policies designed with little more thought than a Greta soundbite will see the region paying 2-3X what they could for natural gas if they favored domestic supply over foreign. Residents are getting used to it (see An Expensive, Greenish Energy Strategy).

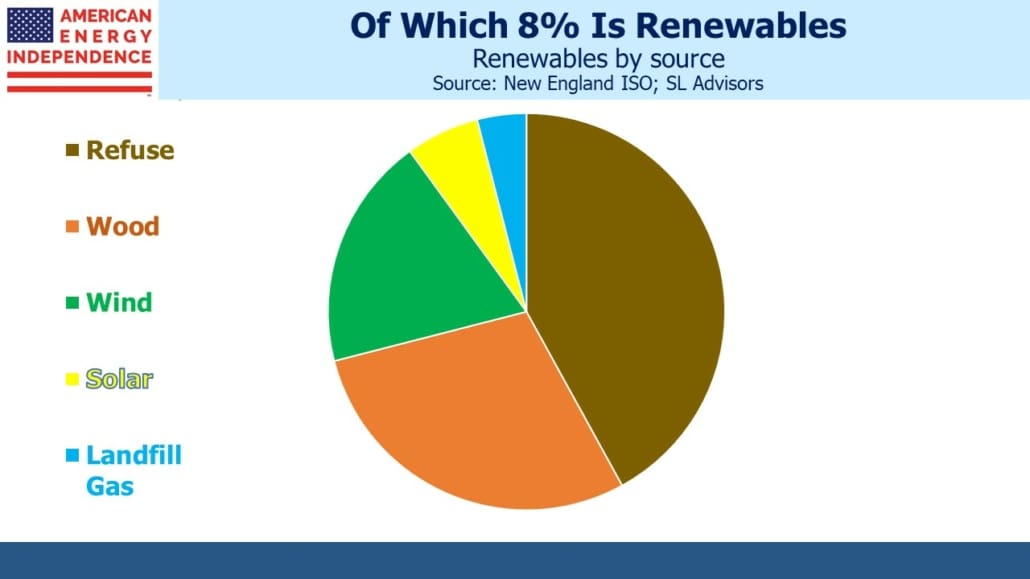

On Monday, the New England Independent System Operator (ISO) reported 74% of its power was being generated using natural gas and 8% renewables. It’s remarkable they can still access that much natural gas given opposition in the region from environmental extremists, but they need to keep the lights on even at the risk of their ESG credentials.

Of the 8% that was from renewable sources, the biggest share was from refuse. Solar and wind were providing around a quarter of renewables so 2% of the ISO’s power — about the same as wood, the burning of which can be more harmful than coal.

New England has the same misguided strategy as Britain (see The Cool North Sea Breeze Lifting US Coal) of believing renewables would compensate for self-imposed reduced access to natural gas. Theirs is another example that should inspire no emulation. But as natural gas pipeline investors, we find ourselves in broad alignment with their results (higher natural gas demand) if not their goals.

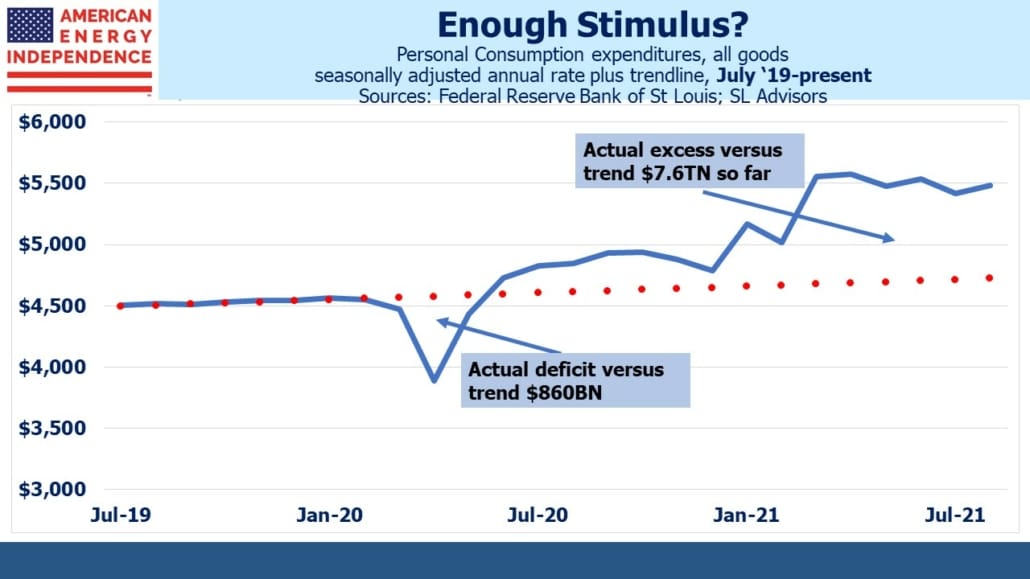

Switching gears, the chart showing Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) on durable and non-durable goods provides further evidence that enormous fiscal and monetary stimulus have put the US economy on a faster, more inflationary growth path than pre-Covid.

The trendline over two decades provides a reasonable estimate of the drop in PCE (all goods) caused by Covid. The area beneath the trendline represents $860BN of purchases. Since then, Federal stimulus has driven an excess of consumption over this trendline of $7.6TN, almost 9X the shortfall. And that’s so far – future consumption is unlikely to immediately revert back to trend.

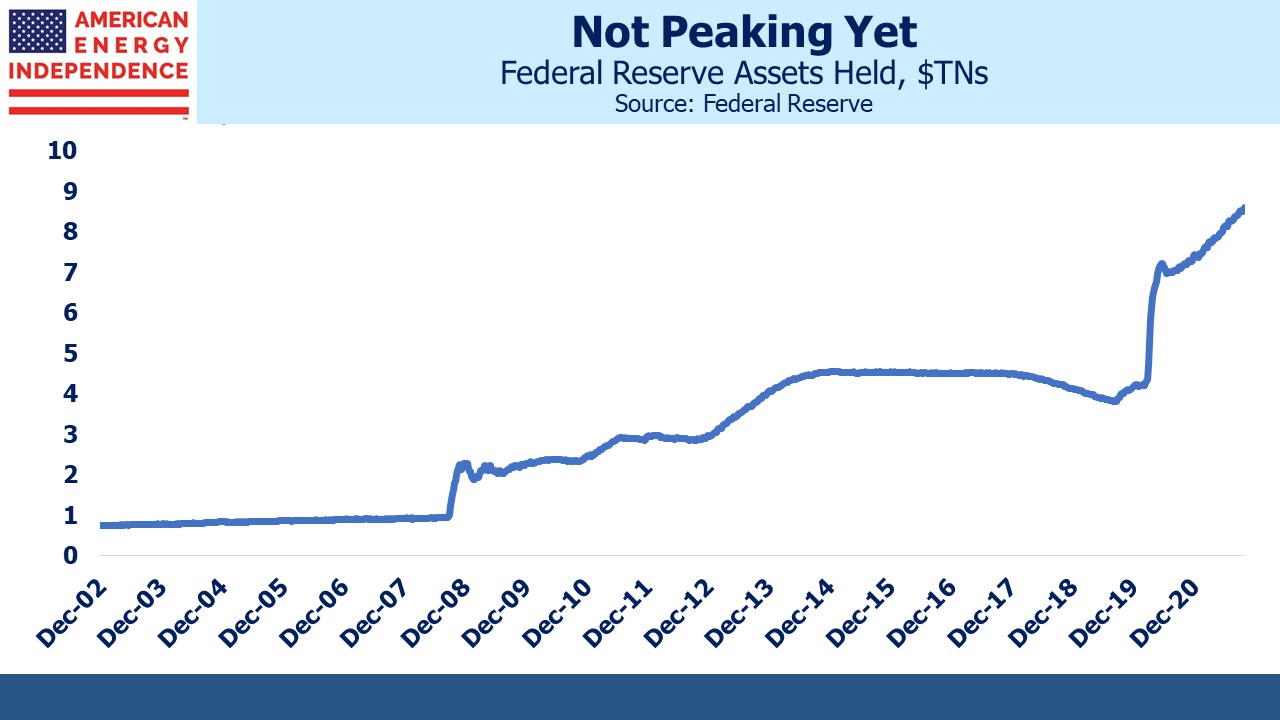

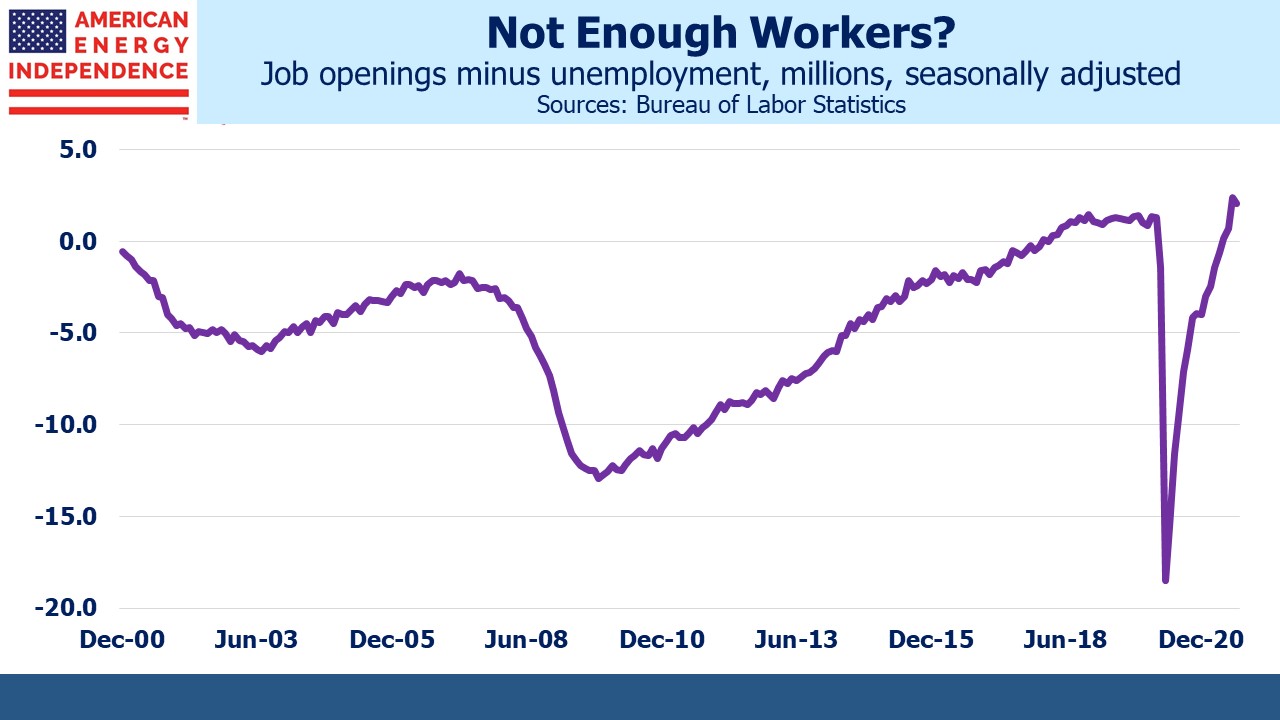

It’s another example of how the initial US fiscal and monetary response to Covid, which was appropriate, morphed into an enormous handout which continues to distort much of today’s economy. Labor and housing are the two biggest examples. The unprecedented number of openings as detailed in Sunday’s blog shows that the labor market is struggling with a skills/location mismatch not a shortage of jobs (see Life Without The Bond Vigilantes). Everyone except the FOMC seems to understand that the housing market has been goosed higher by continued buying of mortgage backed securities.

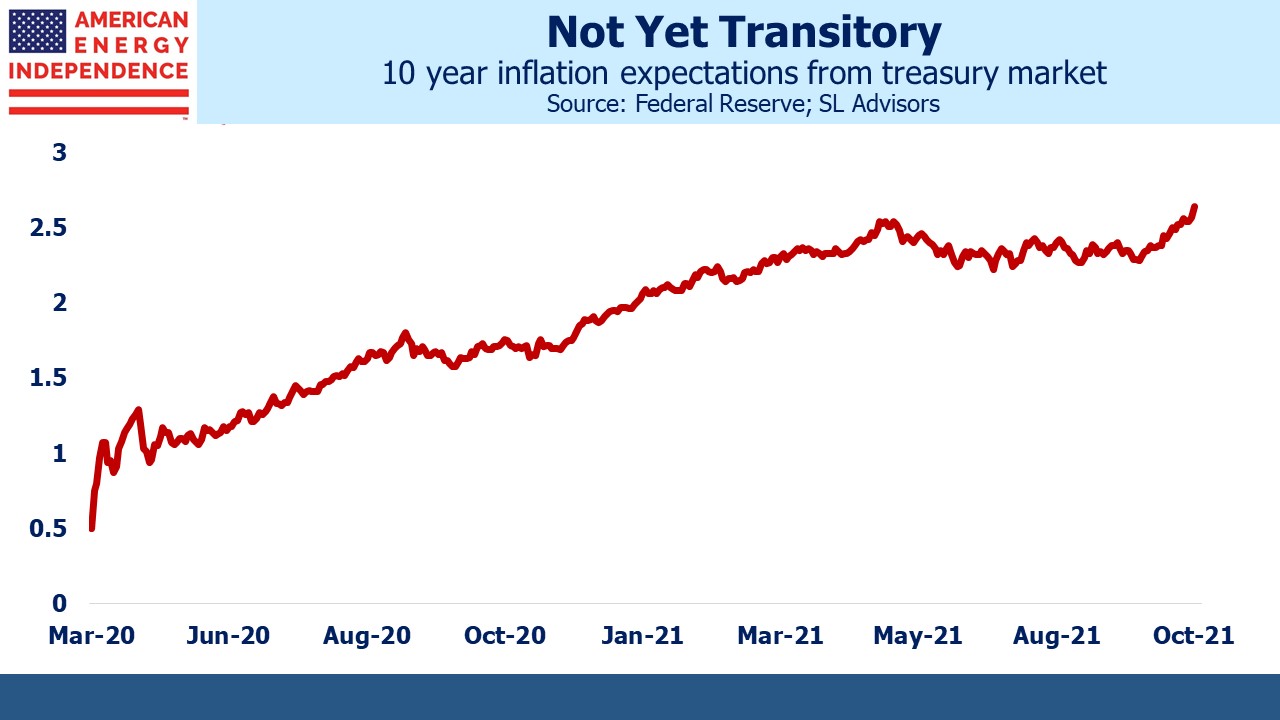

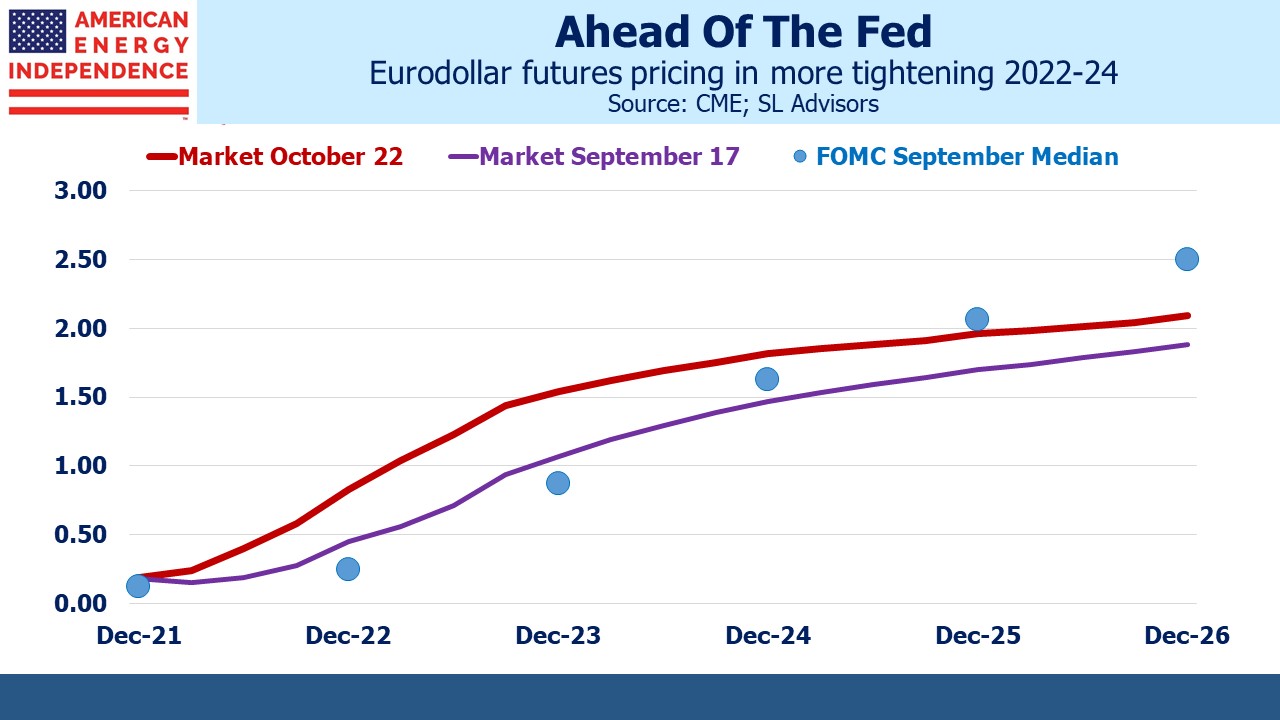

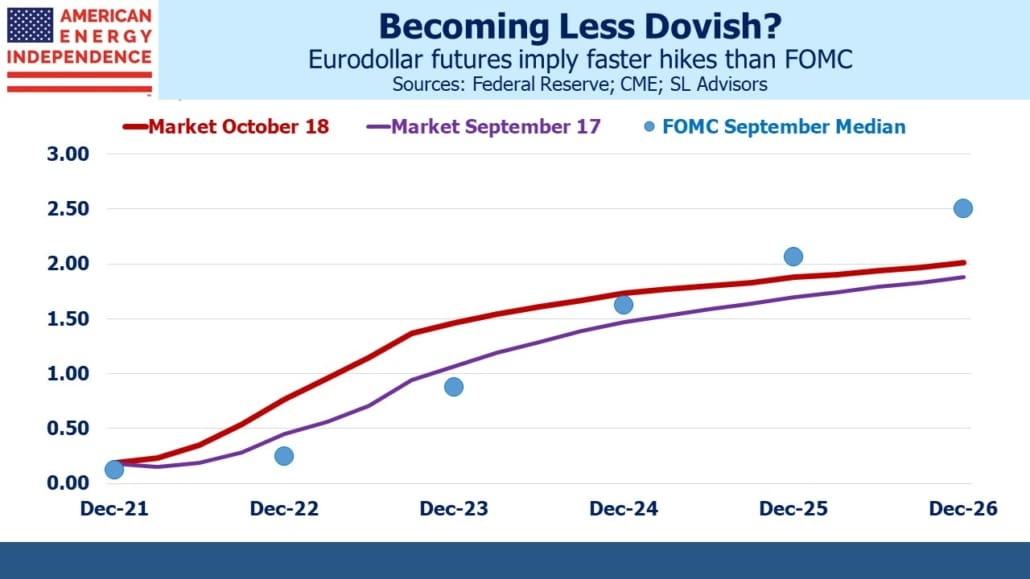

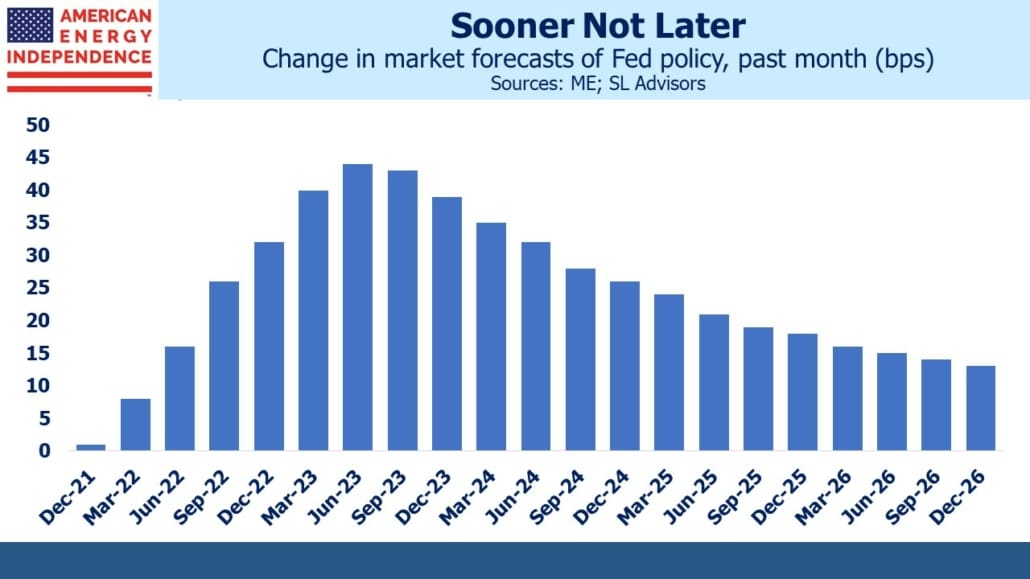

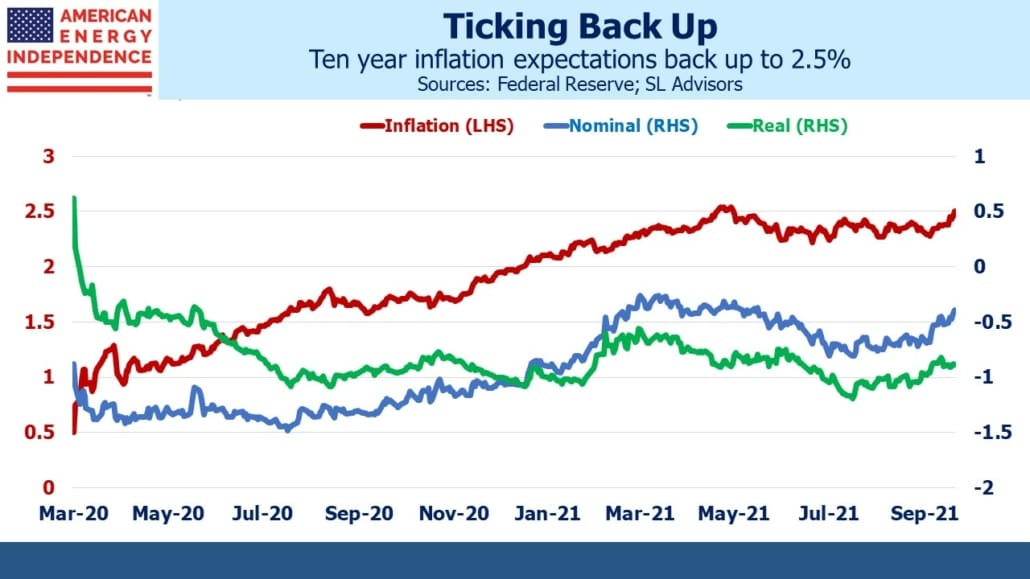

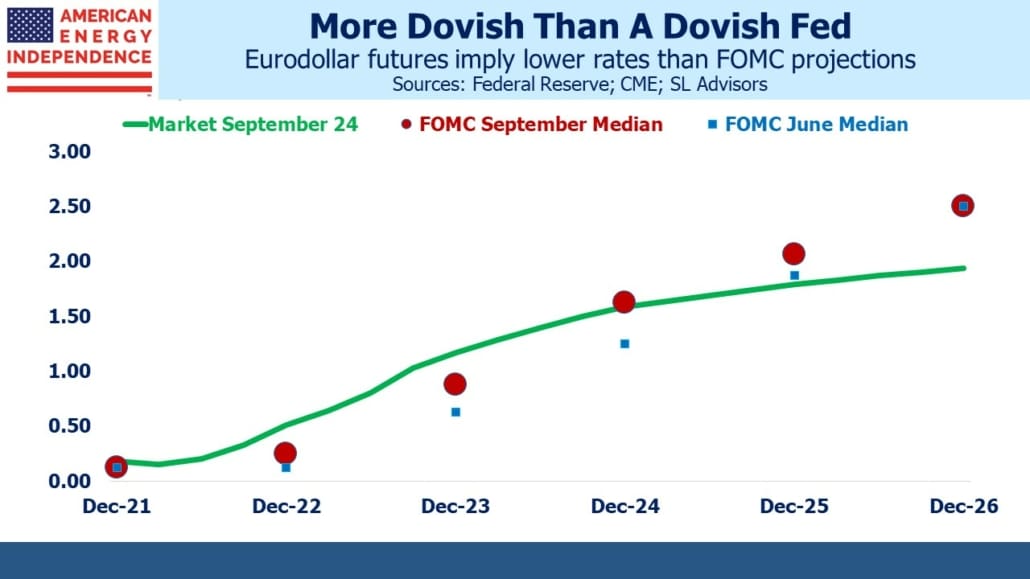

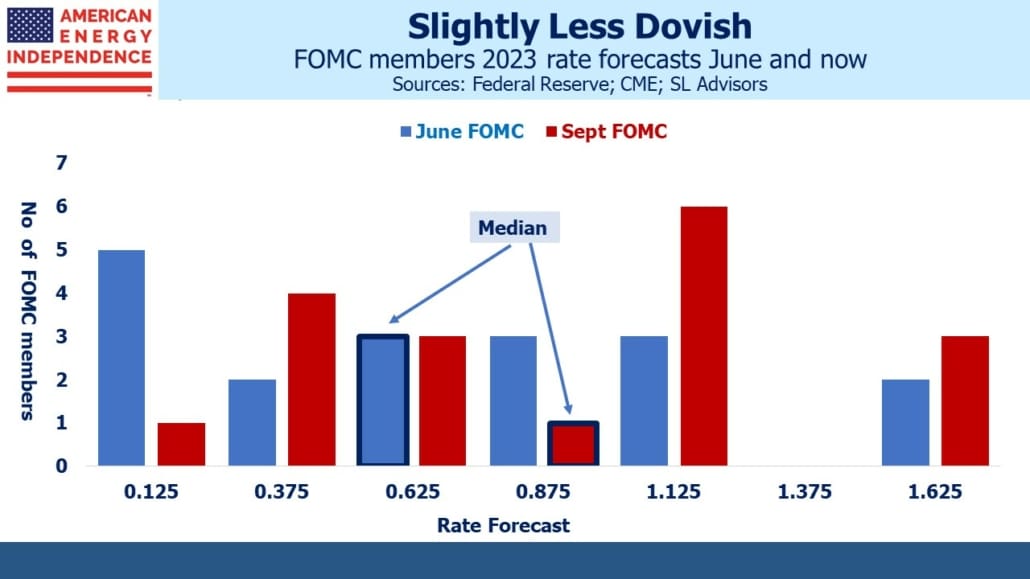

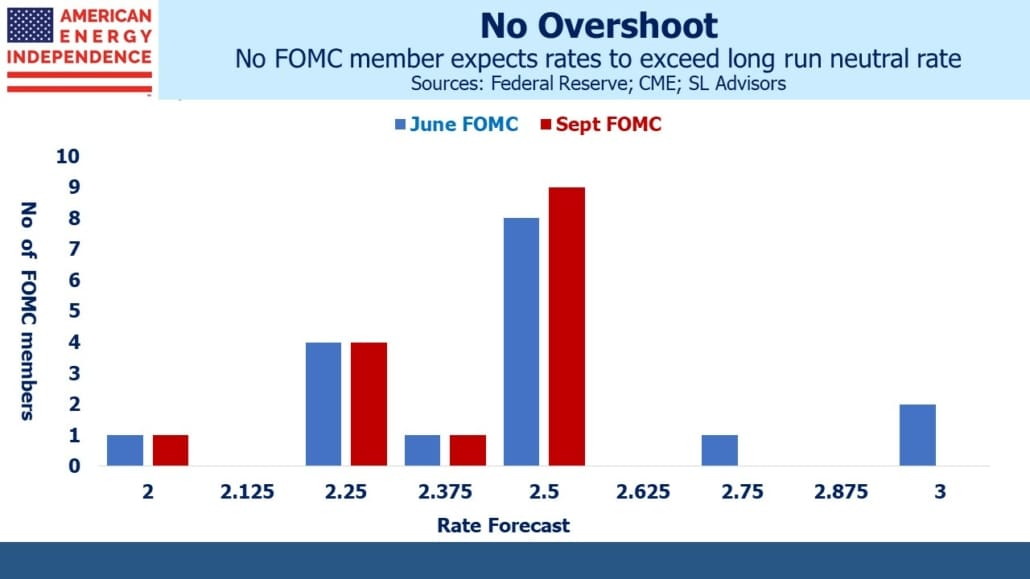

The Federal Reserve is losing any credibility it may have had on inflation. Their singular focus on restoring the shortfall of five million jobs lost since pre-covid is creating all the upside risk on inflation that is confronting investors.

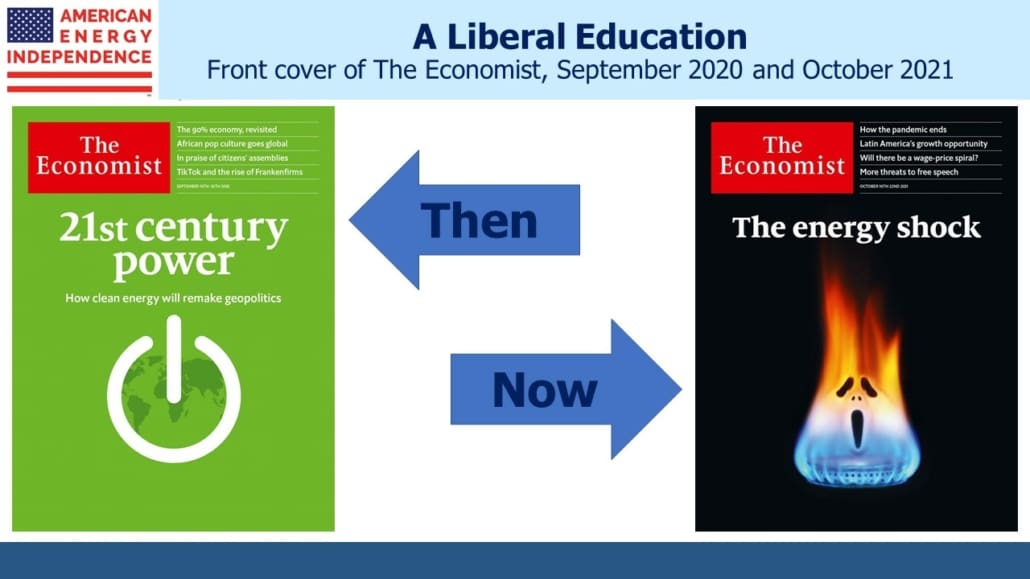

In recent months the energy transition and the exposure of the Federal Reserve’s inflation-seeking agenda have come together as twin threats to the stability of purchasing power. The term “irrational exuberance” was famously coined by Alan Greenspan in the late 1990s to describe the dot.com bubble, and it’s become part of the investment manager’s lexicon. For example, we often describe the pipeline sector as being completely devoid of any exuberance whatsoever, which is why it’s likely to keep rising. Similarly, one of Jay Powell’s less damaging contributions to financial history will be the re-defining of “transitory”, to mean something that is likely to persist longer than expected.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment: