Renewables Are Pushing US Electricity Prices Up

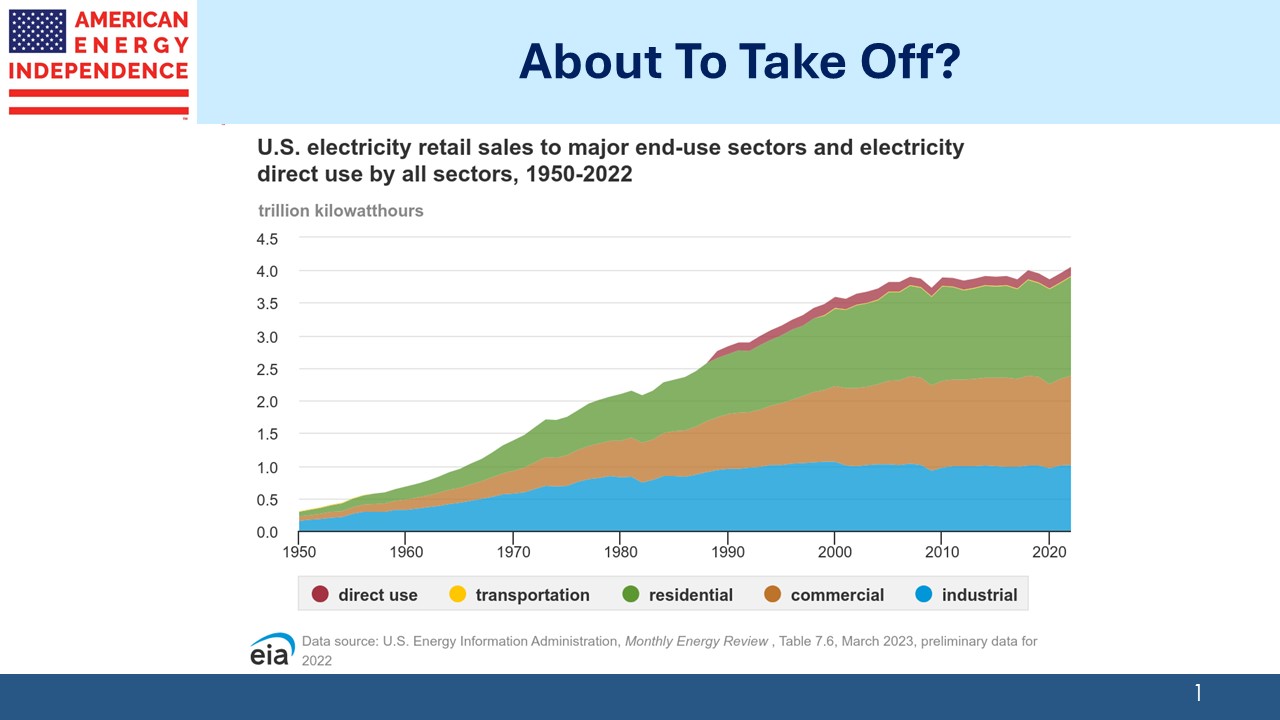

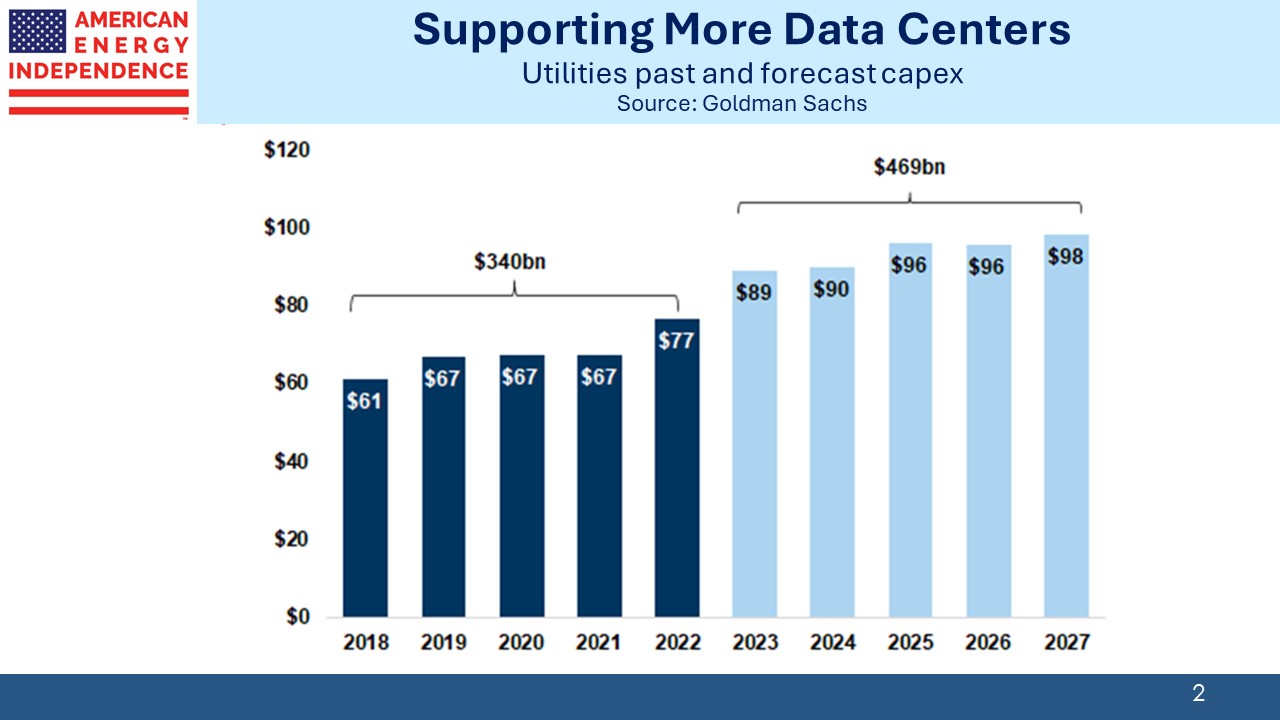

The Artificial Intelligence boom means the need for vastly more computing power. This is leading to a sharp jump in data centers, with a consequent increase in projected electricity demand (see AI Boosts US Energy). Elon Musk noted the pressure this is putting on the supply of electric infrastructure. Electricity is stepped up to very high voltage for transmission before being transformed back down to the familiar 110V we use. For example, generator transformers now have a two-year waiting list.

Most regions of the US are planning for increased power demand. The PJM region attributes it all to data centers. Virginia has added 75 since 2019. Microsoft plans to use dedicated nuclear fusion plants to power its growing AI business.

Shifting to increased use of electricity is a key pillar of the energy transition, since in theory an EV run on solar or windpower generates no CO2 emissions (although its manufacture does). Utilities are at the forefront of delivering more electricity from renewables. This is part of decarbonizing our economy.

The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) published their 2023 Annual Energy Outlook (AEO) almost exactly a year ago. In it they projected a 0.7% annual increase in power consumption. By July they had concluded that their models needed an overhaul to better model hydrogen, carbon capture and other emerging technologies. So they’re skipping this year’s AEO while they do that and will return next year with the 2025 AEO.

In January last year PJM forecast 1.4% annual demand growth for electricity over the next decade. Two months ago, they raised this to 2.4% over their ten-year planning horizon. It’s safe to assume that next year’s long term outlook from the EIA will assume faster demand growth.

NextEra Energy (NEE) says it “has a plan to lead the decarbonization of America.” On their most recent earnings call, management’s enthusiasm about growth opportunities in renewables reminded me of pipeline companies 7-10 years ago during the dash for growth that was the shale revolution. There’s an unfailing confidence that growth is good. For investors that requires that projects will earn a risk-adjusted return above the company’s weighted average cost of capital.

Alot of shale revolution capital was poorly allocated. Too many projects, both upstream and midstream, failed to generate a return above their cost of capital.

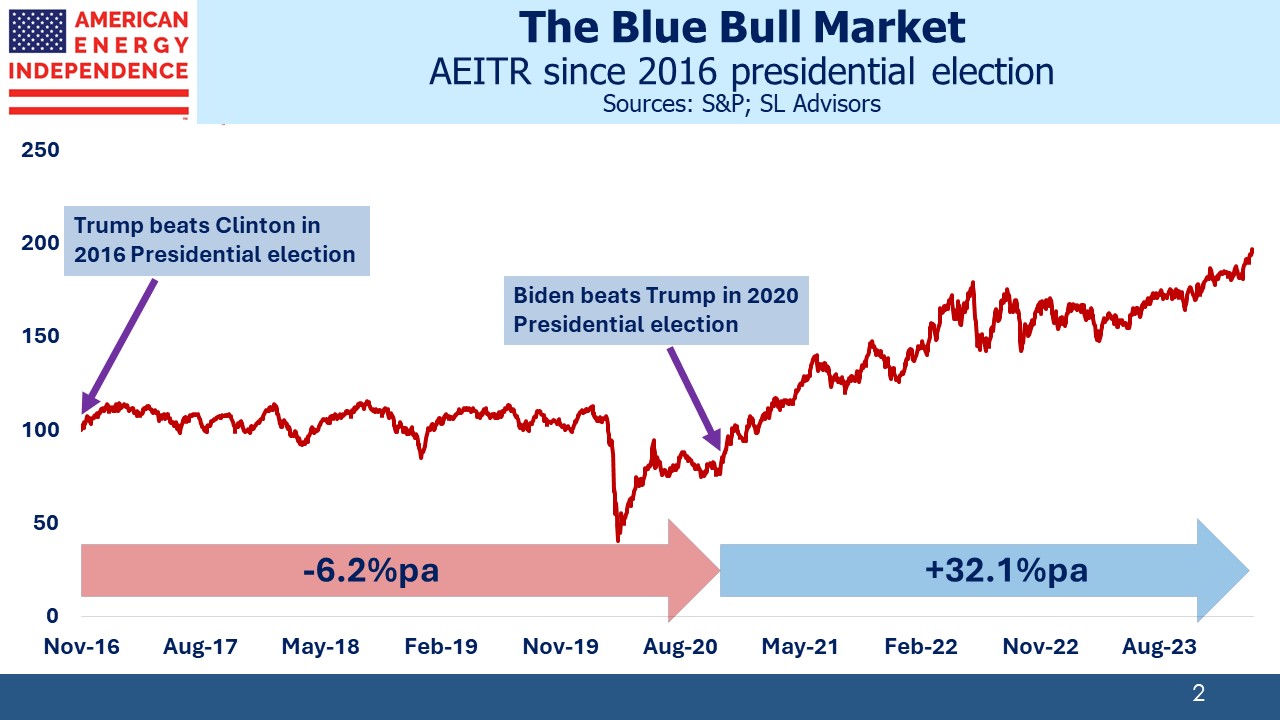

The energy transition and build-out of renewables originally came with much excitement and enthusiasm. Democrat political leaders were partly to blame. Joe Biden promised cheap reliable electricity along with well-paid union jobs. Climate extremists have long misrepresented the actual cost of intermittent solar and wind power.

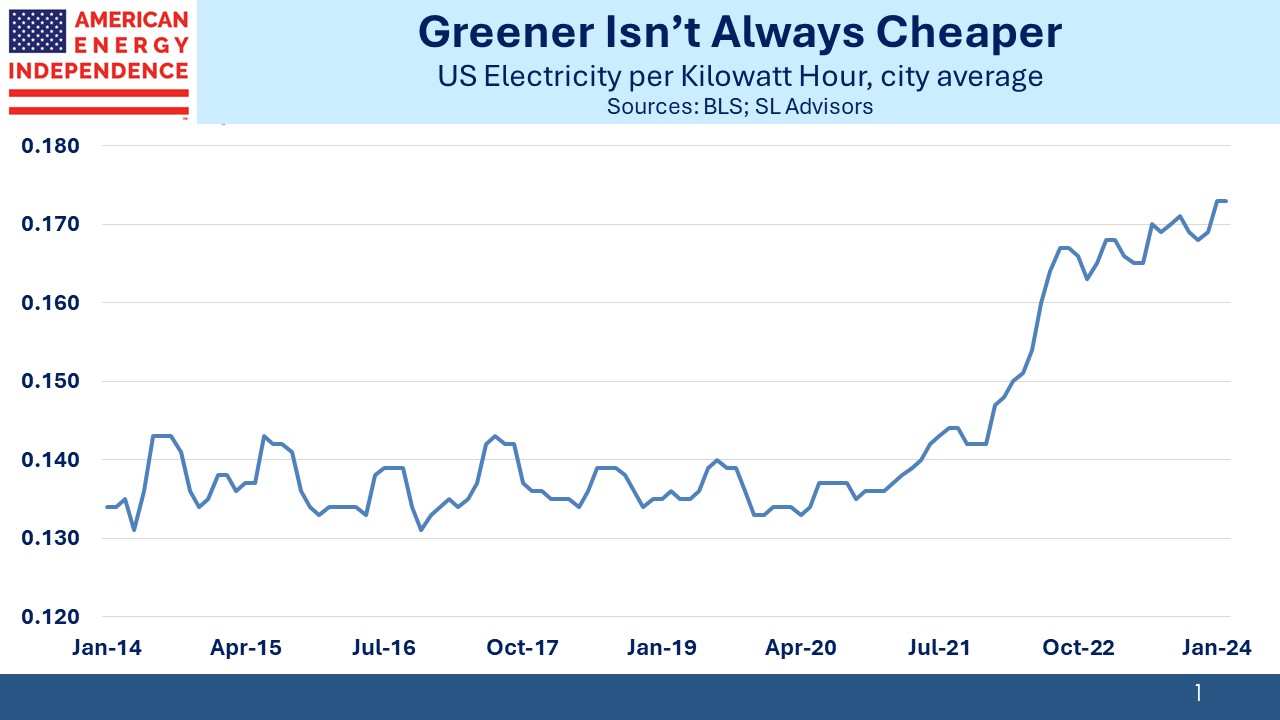

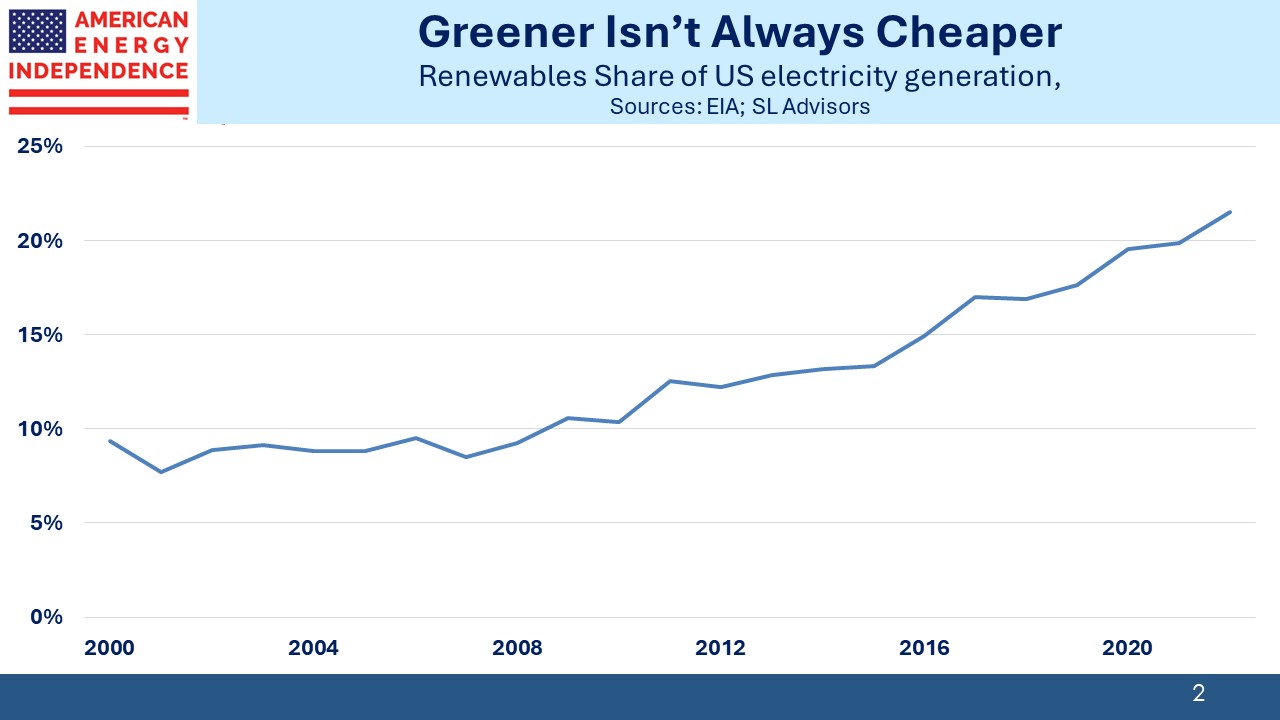

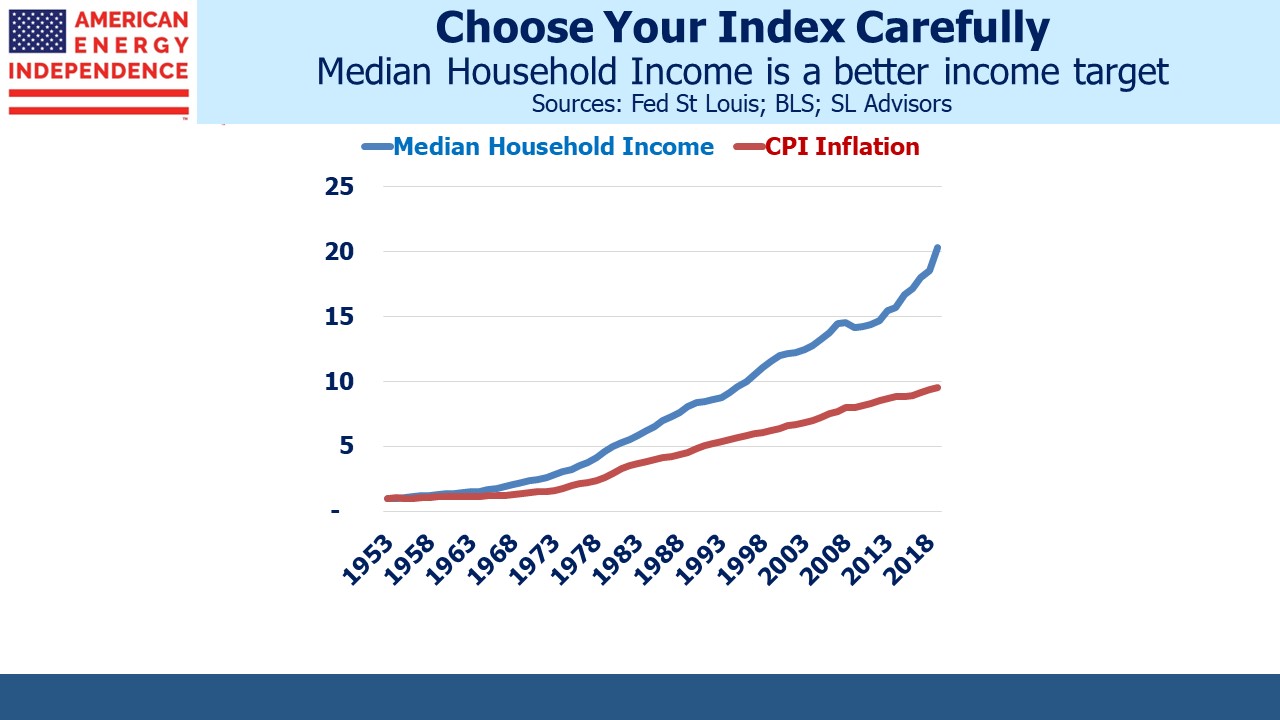

US electricity prices are climbing. Over the past five years they’ve increased at a 4.9% annual rate, 0.7% faster than the CPI. Renewables’ share of US power generation has been climbing for two decades and is now around 22%. It’s not a coincidence.

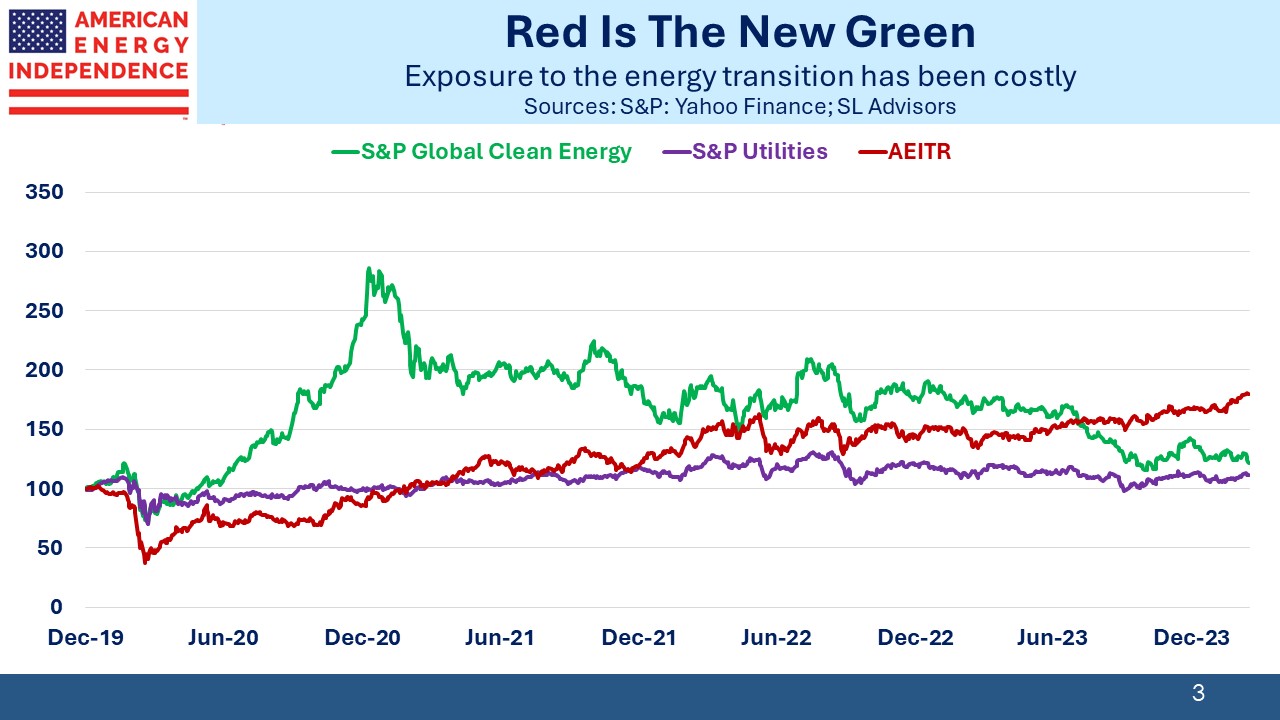

The S&P Global Clean Energy index peaked in late 2020. NEE peaked a year later. US electricity prices had long fluctuated between 13.0 and 14.5 cents per Kilowatt Hour (KwH), but around the time that inflated renewables expectation began to sag, power prices rose.

Fortunately we’re nowhere close to Germany, proud leader of the energy transition, where wholesale electricity is around US0.55 per KwH.

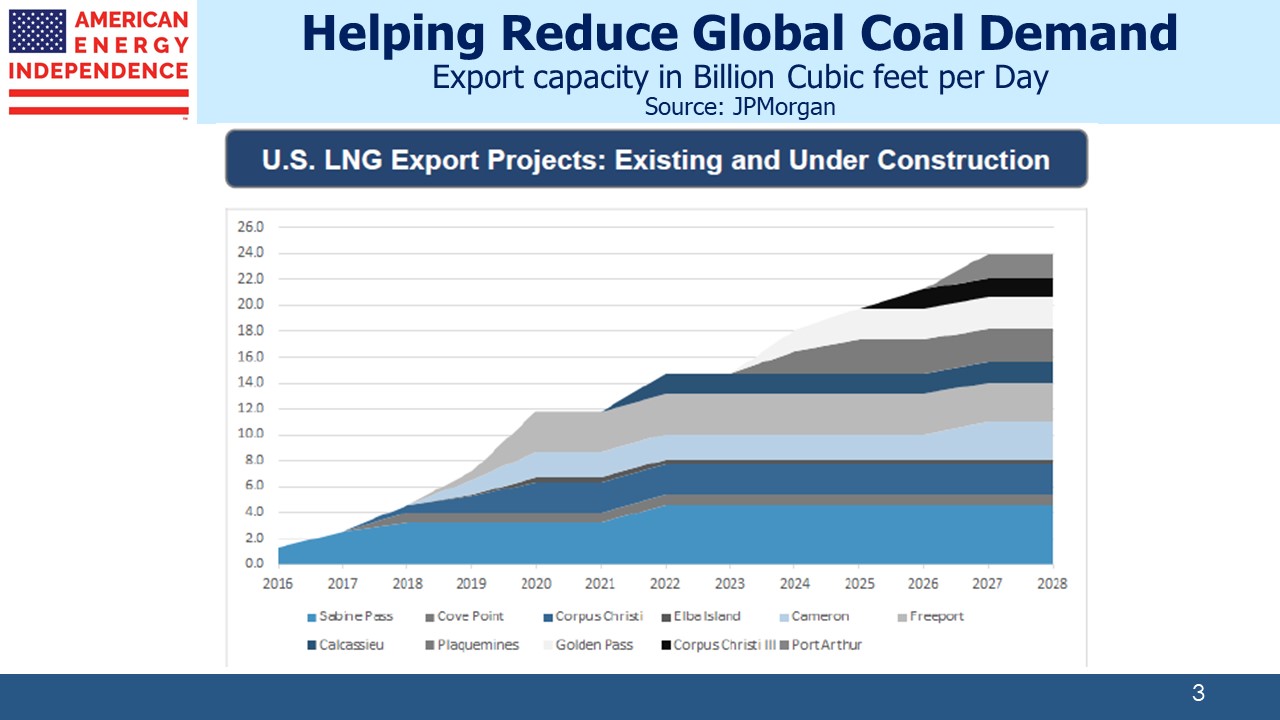

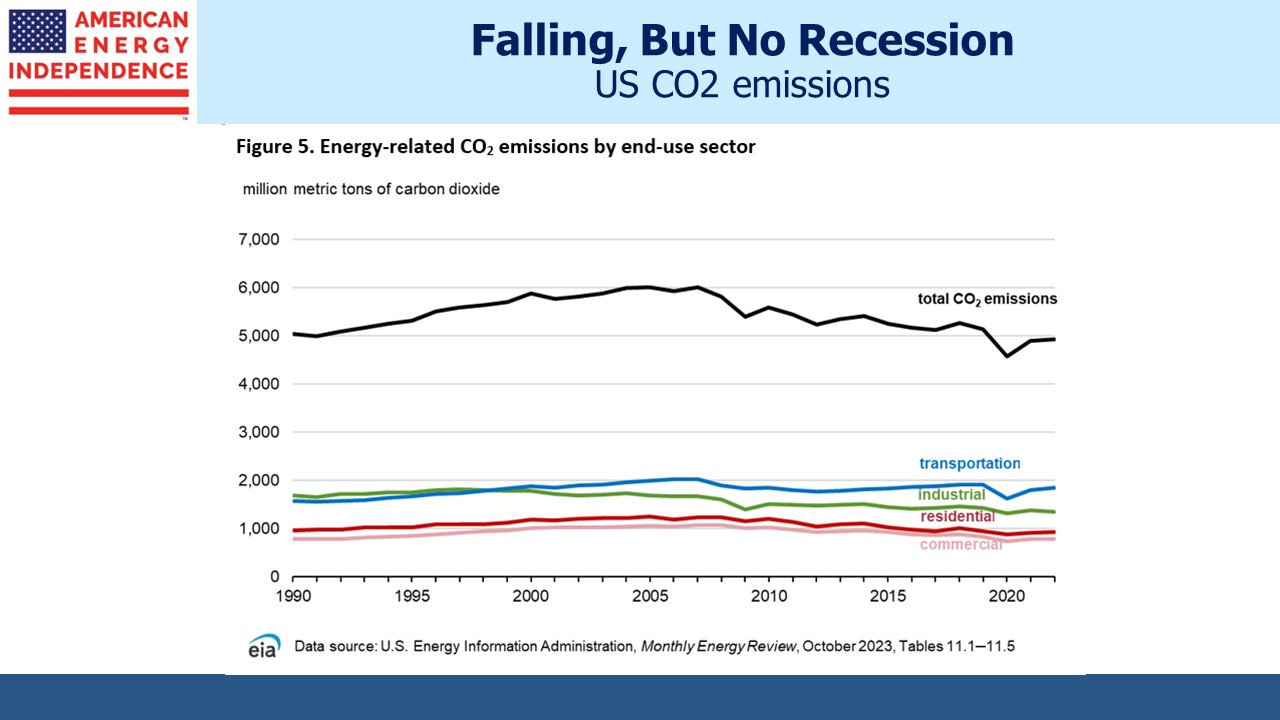

This blog is in favor of reducing CO2 emissions. As we tirelessly point out, replacing coal with natural gas remains America’s biggest success on this score. But few consumers want to pay more for energy – and who can blame them when climate extremists have long asserted with no evidence that renewables are cheaper as well as better for the planet. As a result, few expect to pay more for the energy transition.

Climate extremists have overpromised on the solution.

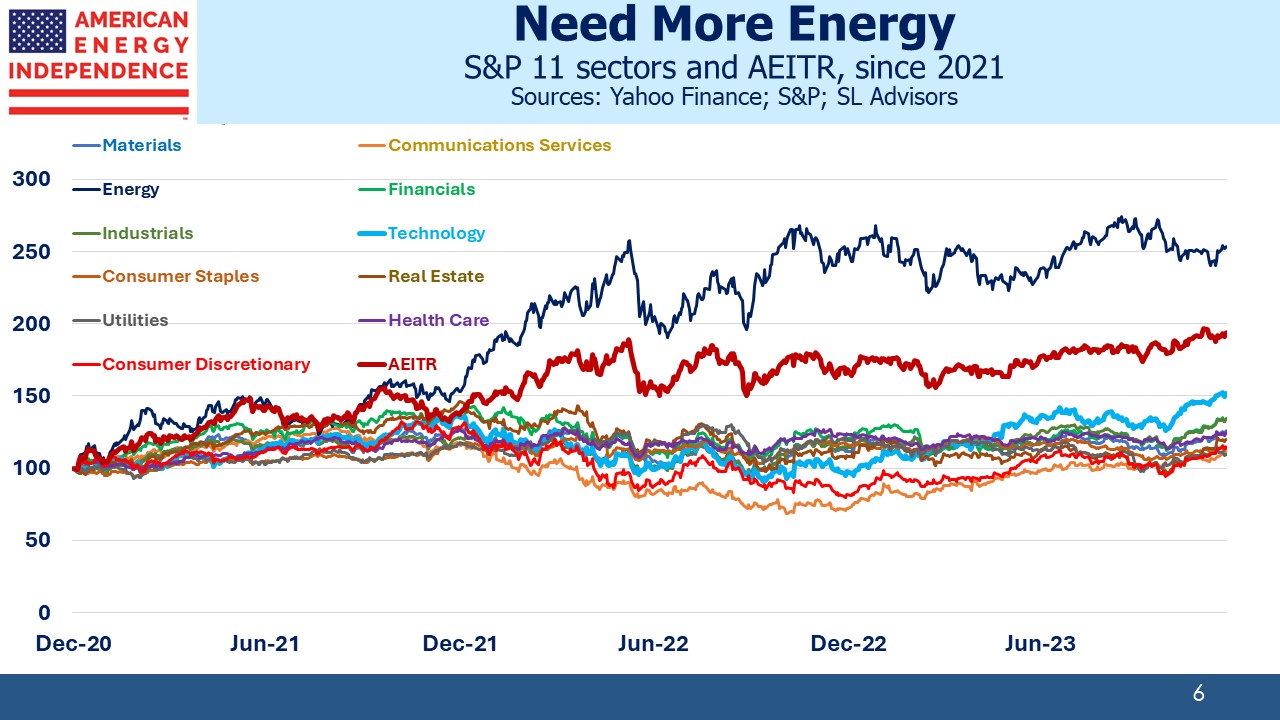

This puts utilities in an unenviable position. They’re at the forefront of what many believe is a vital mission to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but investors are souring on them. NEE management conceded on their recent earnings call to be disappointed with their stock performance, which is 2.2% pa over the past five years.

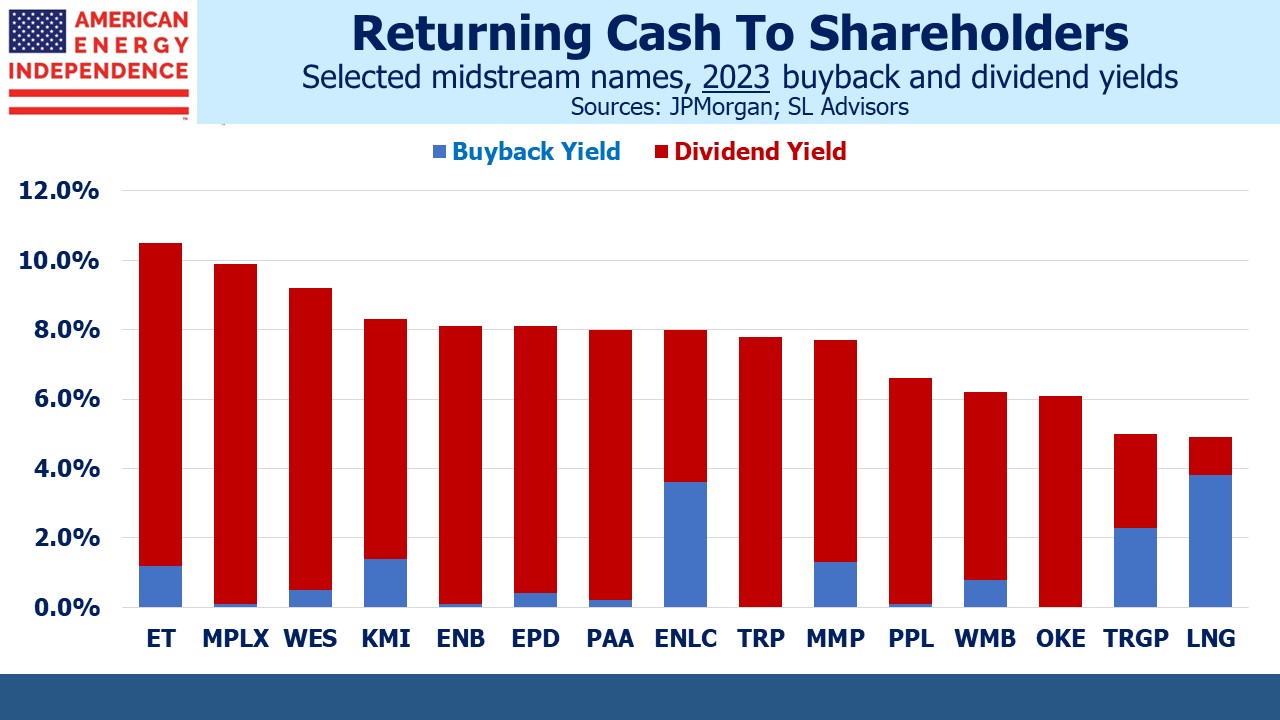

The sudden growth in data centers will likely put further upward pressure on electricity prices, since for most utilities at the margin adding new capacity is likely to cost more than their current average cost. Socializing the cost of added data center demand across all their customers will be unpopular, and it will also require more traditional energy. Natural gas infrastructure will benefit, and planned coal plant retirements might be delayed. JPMorgan expects Williams Companies (WMB) could see 0.75 billion cubic feet per day of incremental throughput on their natural gas pipeline network, and projects, “the total national opportunity potentially multiples of this figure.”

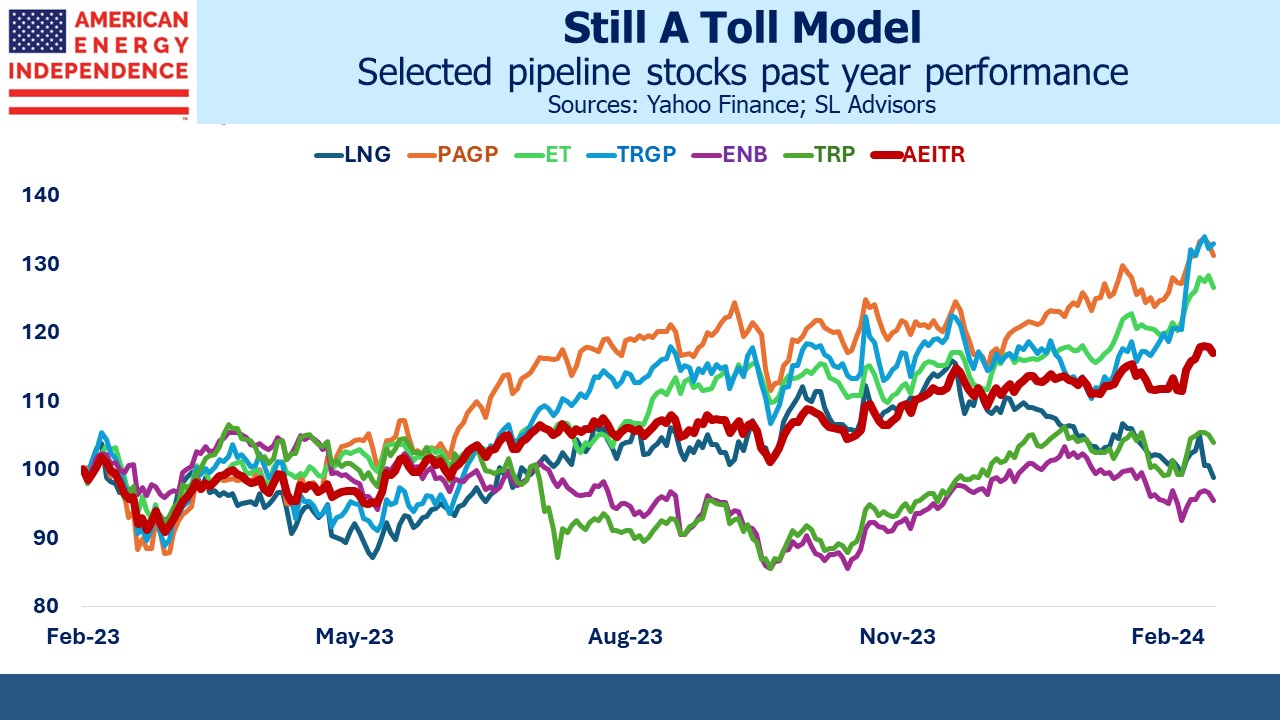

Where the pipeline sector differs from utilities is that they’ll often meet incremental demand with small additions to existing capacity, usually funded organically. They don’t have the same pressure to deliver the energy transition at a cheap price.

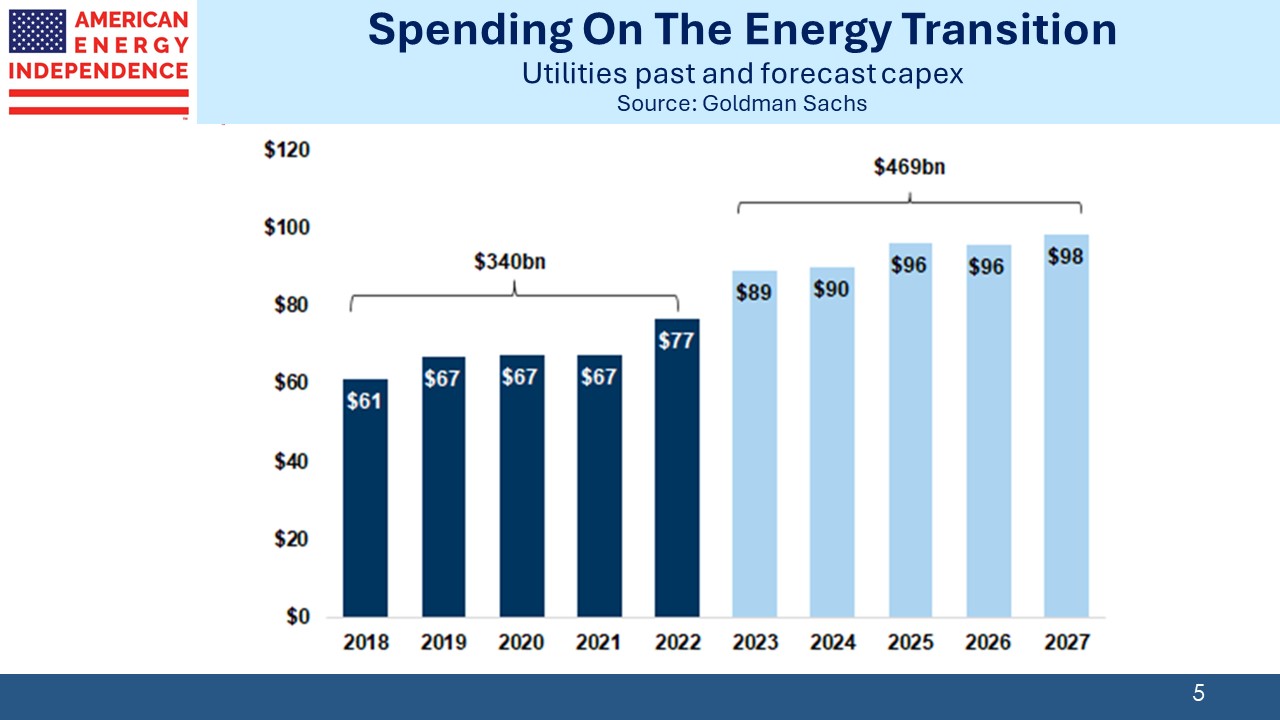

Utility investors are learning to be less enthusiastic about capex-funded growth.

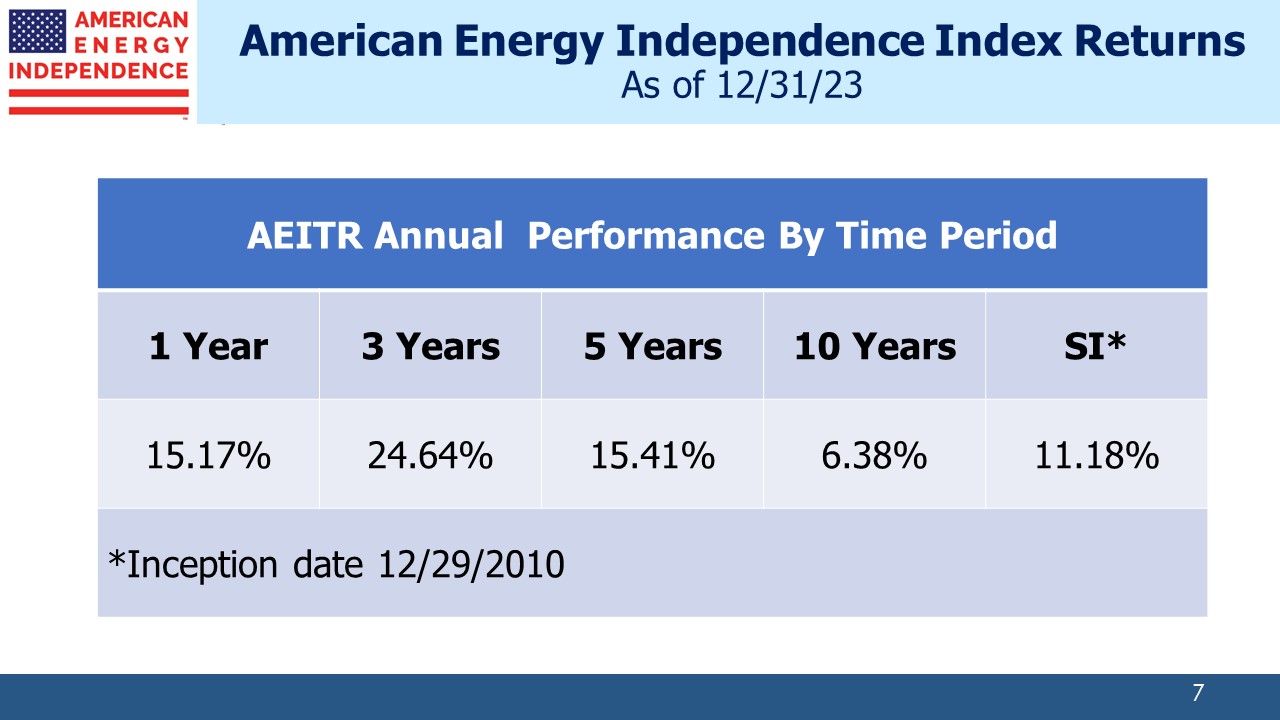

We have three have funds that seek to profit from this environment: