Energy Transfer: Cutting Your Payout, Not Mine

Too few writers covering energy infrastructure admit to the many distribution cuts inflicted on MLP holders. Instead, they identify numerous other problems whose resolution will draw in buyers. Incentive Distribution Rights (IDRs), the payments made by MLPs to their General Partners (GP), have drawn scorn for the past couple of years. Eliminating them is fashionable and now virtually complete, with only a handful of holdouts. Other solutions include self-funding growth projects. Common practice was for MLPs to pay out most of their cash and raise equity for new projects. It worked until the new projects became big. The Shale Revolution was responsible for that. Selling non-core assets is another piece of advice – it’s rarely controversial. Few companies admit that any assets are non-core, until selling them.

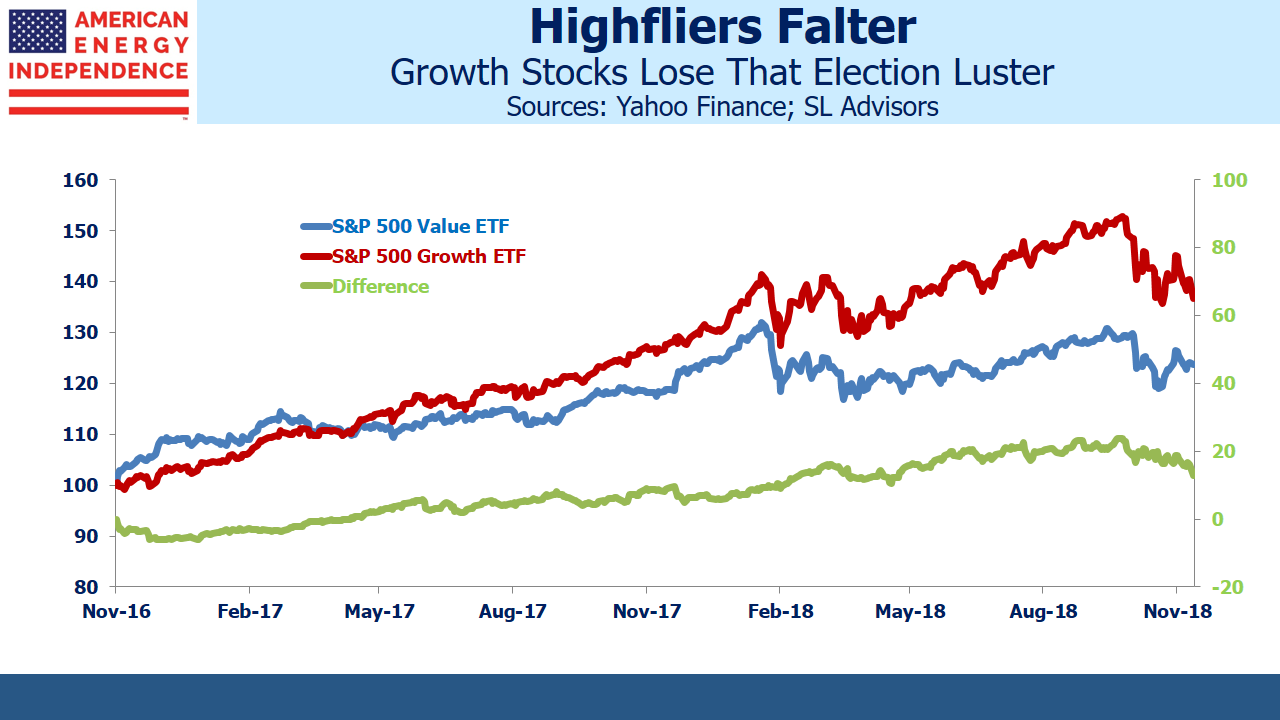

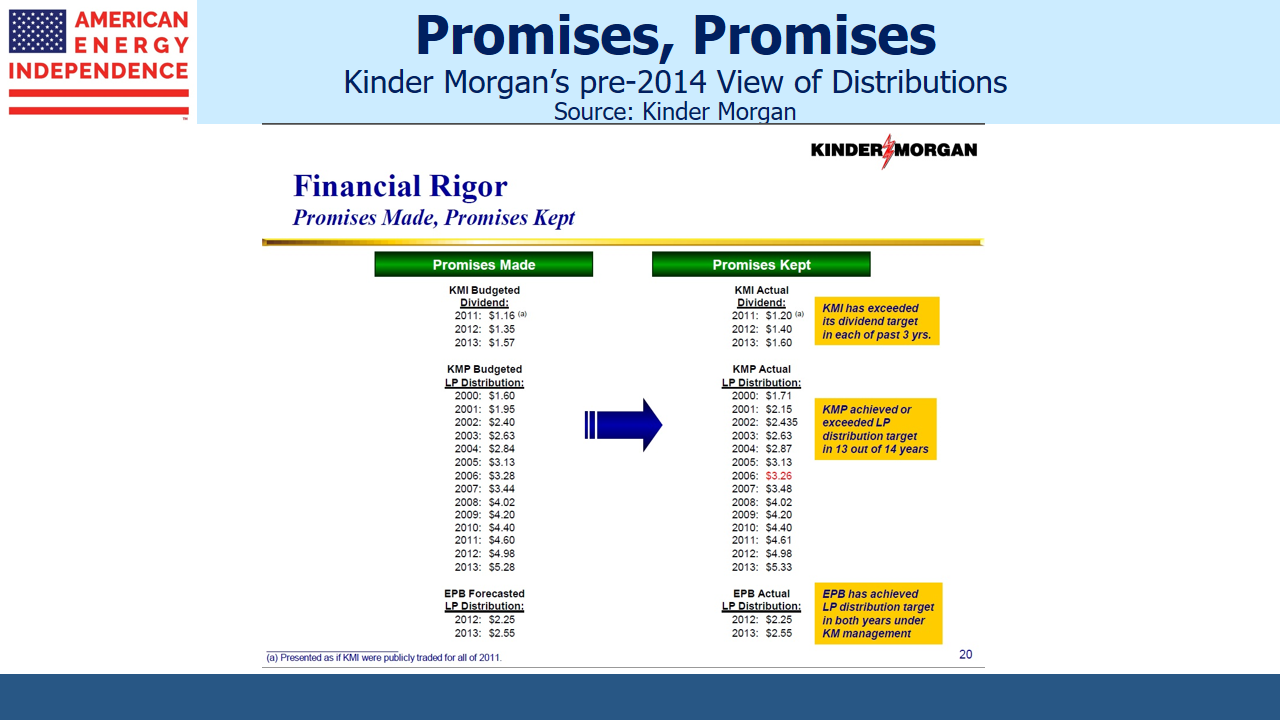

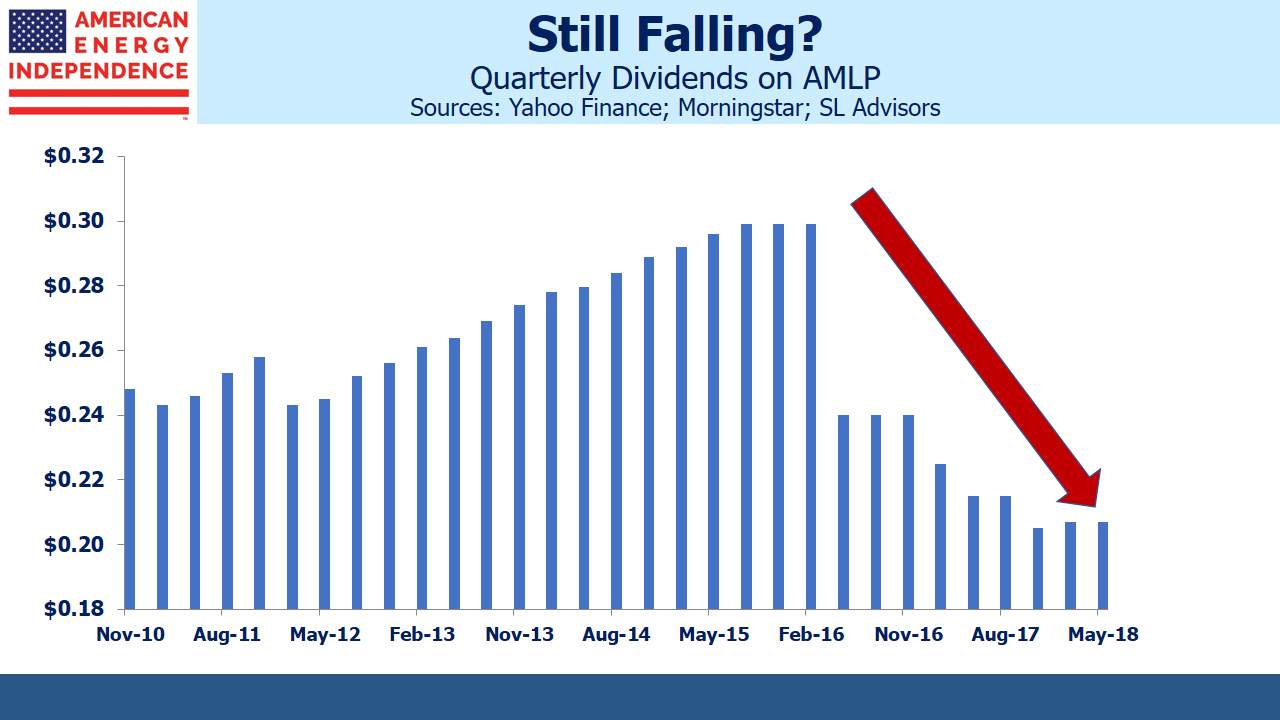

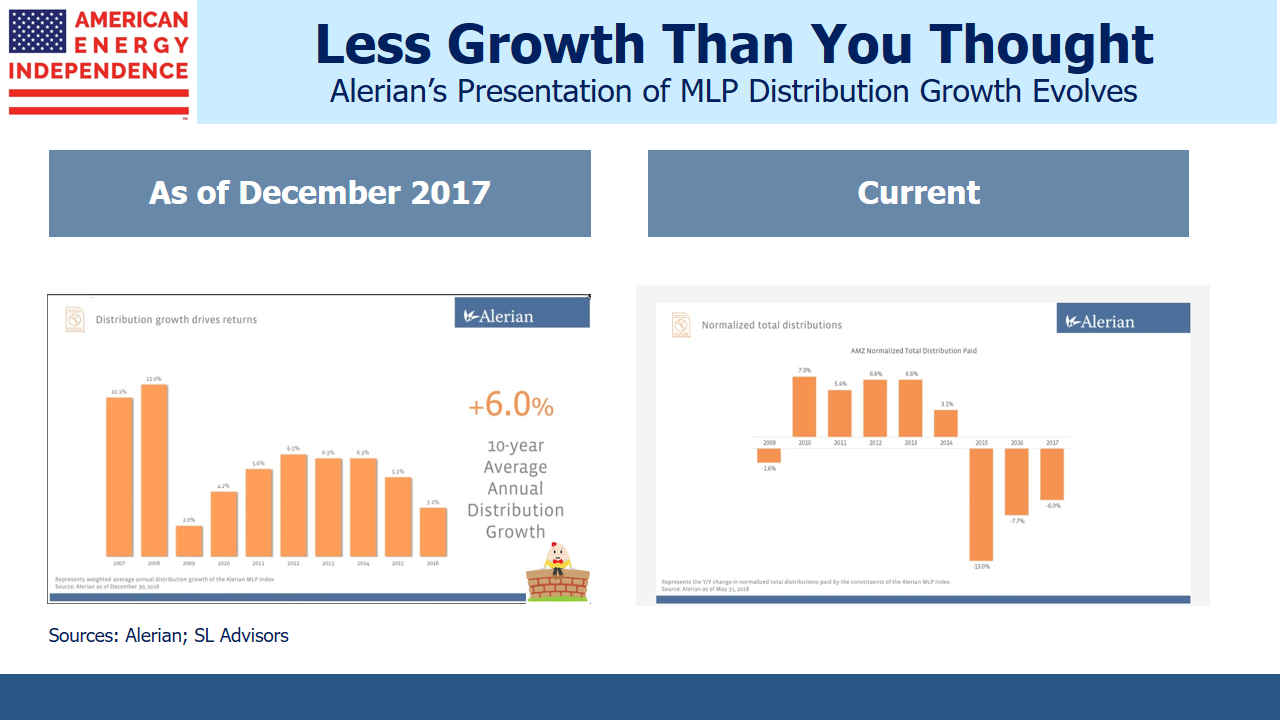

All this free advice is directed both publicly and privately to help draw in new investors and lift stock prices. What’s rarely mentioned are the widespread and substantial cuts in distributions that have alienated the income-seeking MLP investor base. Alerian has a chart showing “AMZ Normalized Distributions Paid”, which shows a cumulative 25% cut 2015-17, if you do the math. Dividends on AMLP are down 34% from their high in 2014, although you won’t find this on their website. Promises have been broken, and the buyers know this.

One reason others don’t dwell too much on this issue is that many distribution cuts have been via mergers and simplifications. When a lower yielding GP acquires its MLP, the MLP investors are subjected to a “backdoor” distribution cut through owning a new security with a lower yield than the one they gave up.

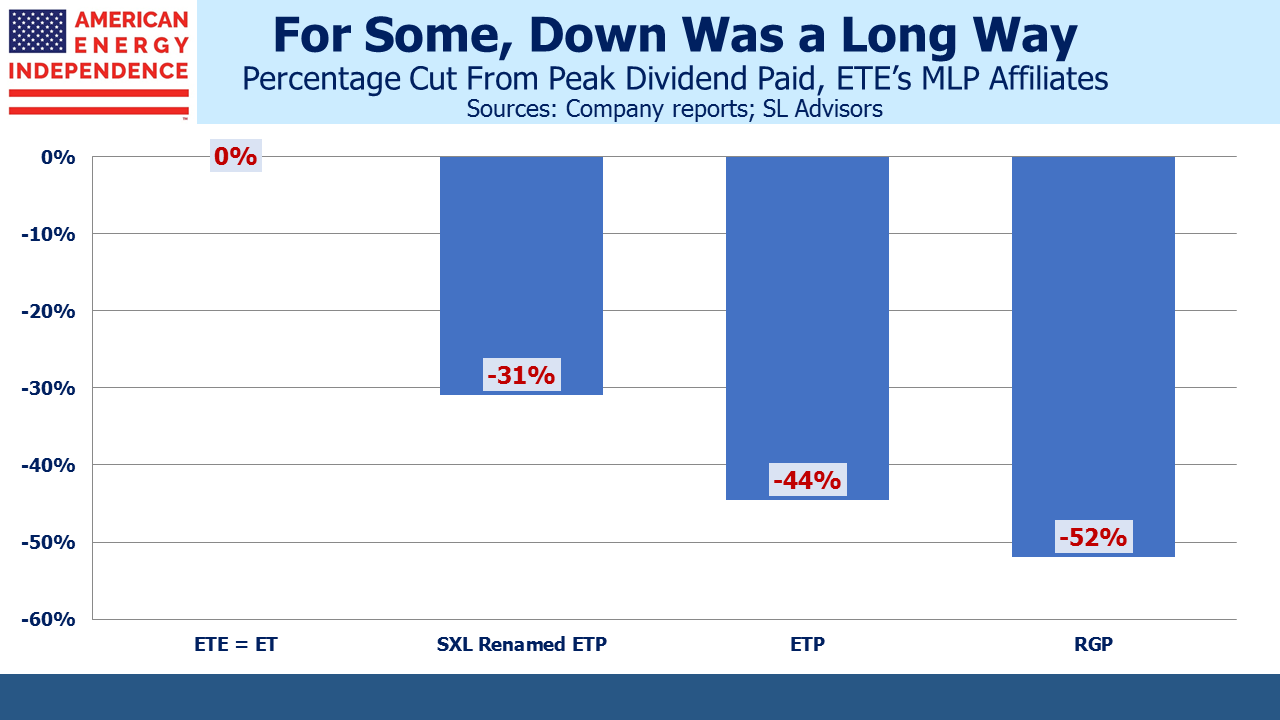

Energy Transfer has excelled at imposing such “stealth distribution cuts”. Over the past four years they’ve rolled four publicly traded entities into one. In each case, the lower-yielding entity acquired the higher-yielding one, resulting in a lower distribution for investors in the acquiree.

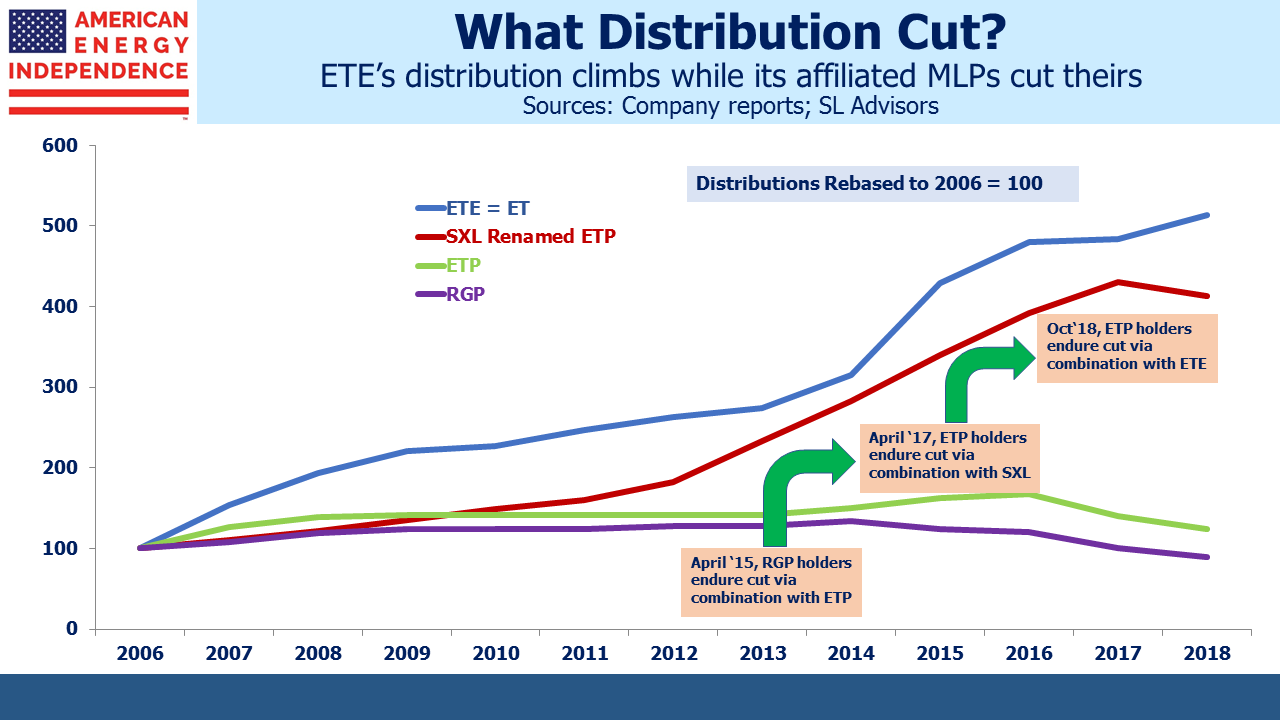

What’s striking is to overlay the normalized distribution history of the four entities: Energy Transfer Equity (ETE), Energy Transfer Partners (ETP), Sunoco Logistics (SXL) and Regency Partners (RGP). ETE is the surviving entity, now renamed Energy Transfer (ET).

ETE investors have seen a five-fold increase in distributions since 2006, a 13% compounded annual growth rate. They’ve increased distributions every year. That shouldn’t be surprising, because ETE was always the vehicle of choice for CEO Kelcy Warren and the management team. SXL holders had a good run – in 2016 they folded in higher-yielding ETP but retained the ETP name, which gave them a 14% distribution growth rate to that point. But then they were “Kelcy’d”, as ETP adopted ETE’s lower payout in a subsequent combination, leading to a 31% effective cut. Original investors in ETP and RGP did worse.

ET’s price peaked in 2015 (it was ETE back then), when Kelcy embarked on his ultimately unsuccessful attempt to buy Williams Companies (WMB). It’s a measure of how far sentiment has fallen, in that ETE’s yield briefly dipped below 3% in May 2015. Since then, its distribution has risen from $1.02 to $1.22. They dodged the WMB deal, have reduced leverage, completed the Dakota Access Pipeline and expect to cover their distribution by 1.7-1.9X next year. Nonetheless, today ET yields 8.5%, with an estimated 2019 Distributable Cash Flow yield of 15.9%. No wonder Kelcy Warren is back in buying the stock.

It’s true that ET’s management has earned a reputation for self-dealing. During the protracted WMB merger negotiations , ETE issued very attractive convertible preferred securities to the senior executives, but didn’t make them available to other ETE investors (see Will Energy Transfer Act with Integrity?). Although they won the resulting class action lawsuit, it’s clear that if management can get away with something that benefits them but not shareholders, they will. Even so, the current valuation seems excessively pessimistic.

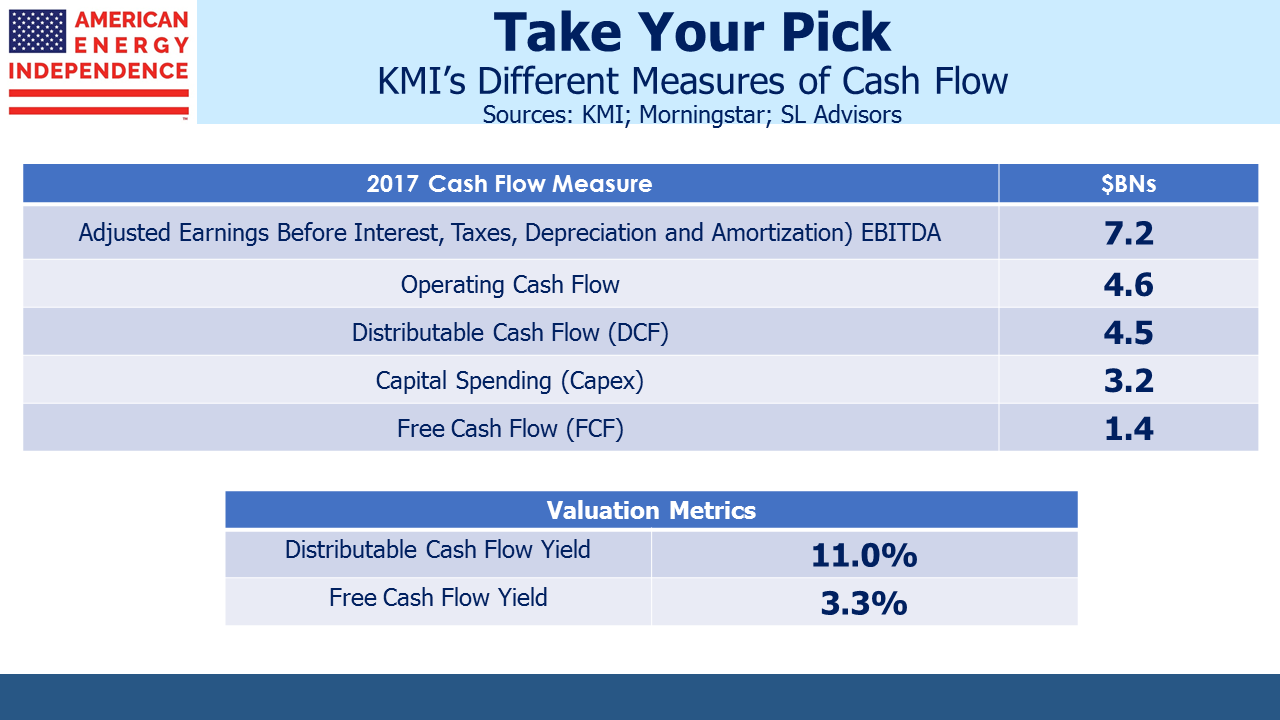

Kinder Morgan (KMI) and Plains All American (PAGP) drew unwelcome attention for each delivering two distribution cuts to their investors. KMI’s first cut was through combining with their MLP in the technique later used by ETE. They followed this up with a second, unambiguous cut in response to rating agency concerns over leverage. PAGP’s management administered two direct cuts, stunning investors both times. Oneok (OKE), Targa (TRGP), Semgroup (SEMG), and Enlink (ENLC) all folded in their respective MLPs, delivering backdoor distribution cuts to their MLP holders but maintaining their dividends at the GP level. But many others avoided cutting their dividends at all. Antero Midstream (AMGP), Tallgrass (TGE) and Western Gas (WGP) all rolled up their MLPs with no change in payouts.

None of the Canadian midstream companies cut their dividends, reflecting their more conservative approach. This highlights that the distribution cuts were due to the flawed MLP practice of paying out virtually all available cash flow, relying on tapping the capital markets for growth projects. There were a few exceptions, but in general MLP distribution cuts were not due to deteriorating fundamentals in the midstream sector.

MLPs are still cutting payouts. Distributions on AMLP, which is MLP-only and tracks the Alerian MLP Infrastructure Index, are down 6.9% this year. By contrast, distributions on the American Energy Independence Index, which includes the biggest North American pipeline corporations and MLPs and is therefore more representative of the overall sector, are up 6.6%.

We are invested in AMGP, ENLC, ET, KMI, OKE, PAGP, SEMG, TGE, TRGP, WGP and WMB. We are short AMLP.

SL Advisors is the sub-advisor to the Catalyst MLP & Infrastructure Fund. To learn more about the Fund, please click here.

SL Advisors is also the advisor to an ETF (USAIETF.com).