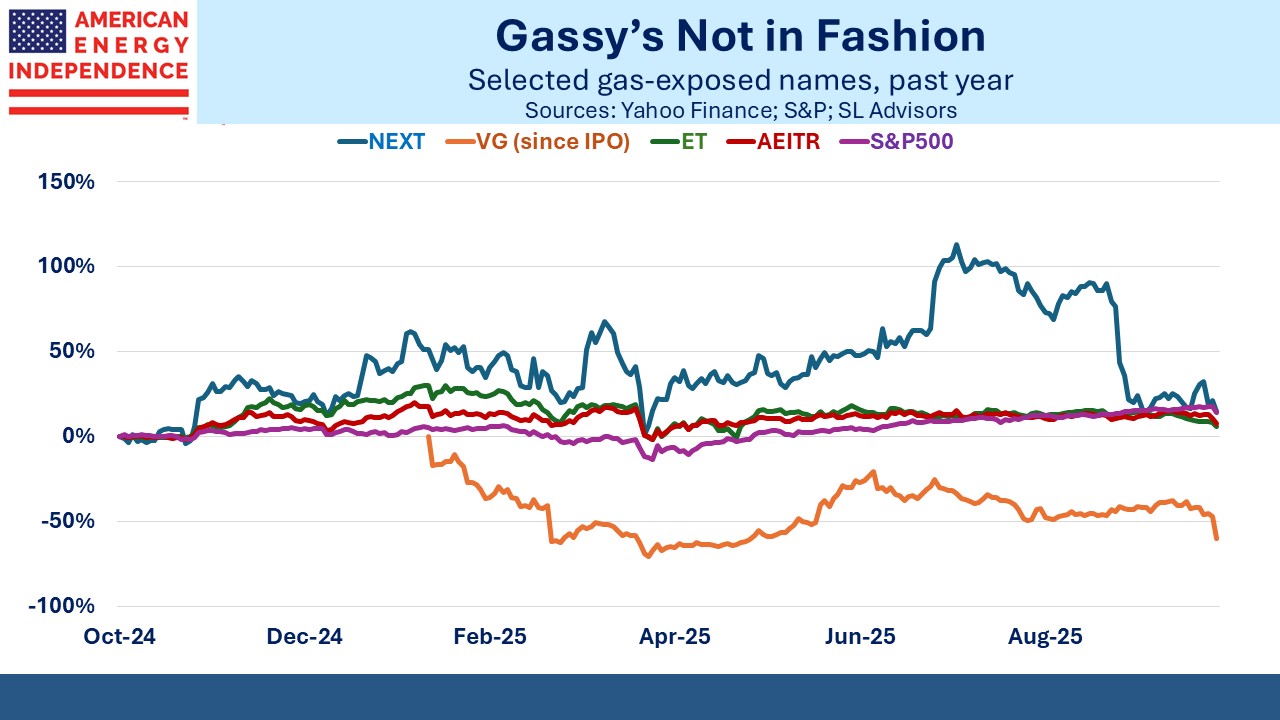

Gassy Isn’t Happy

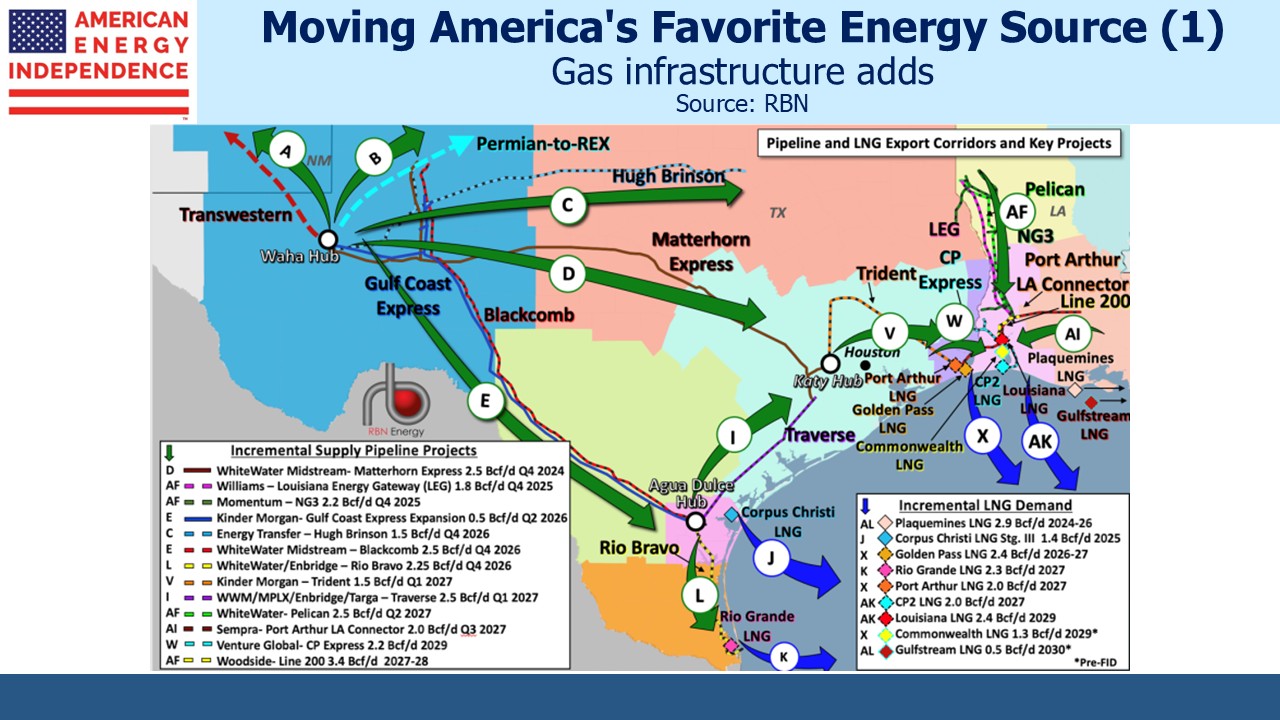

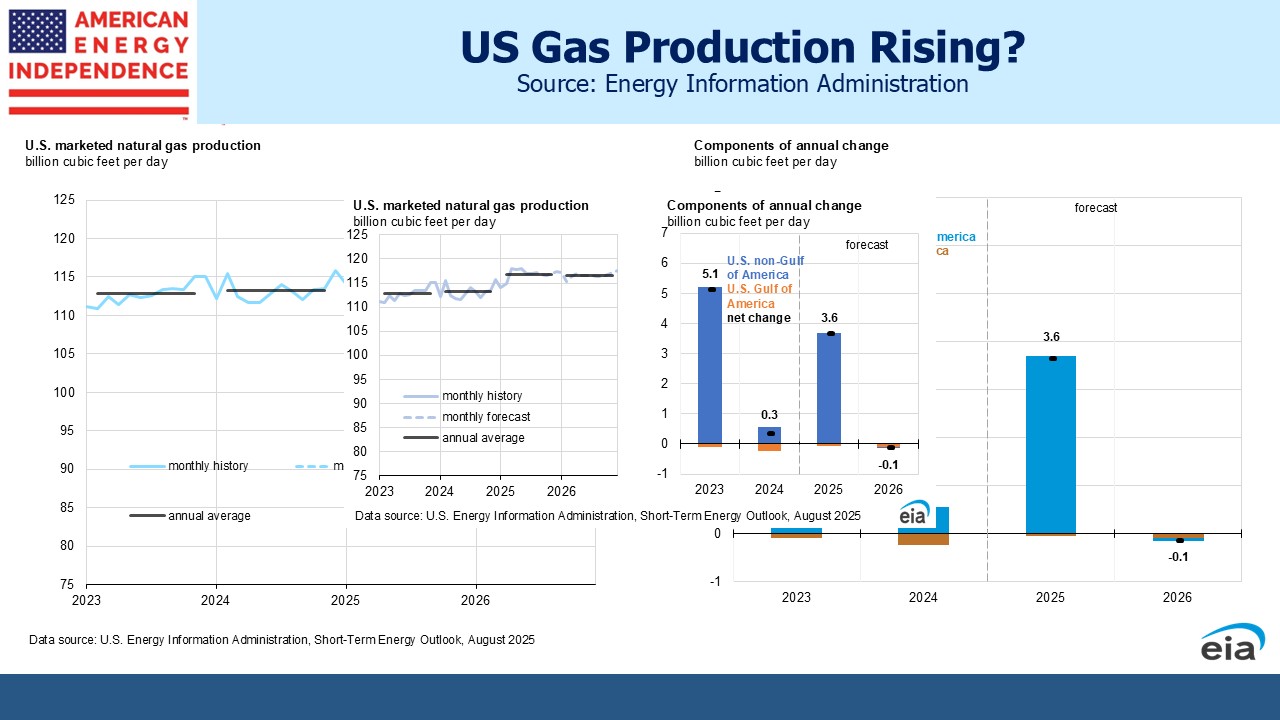

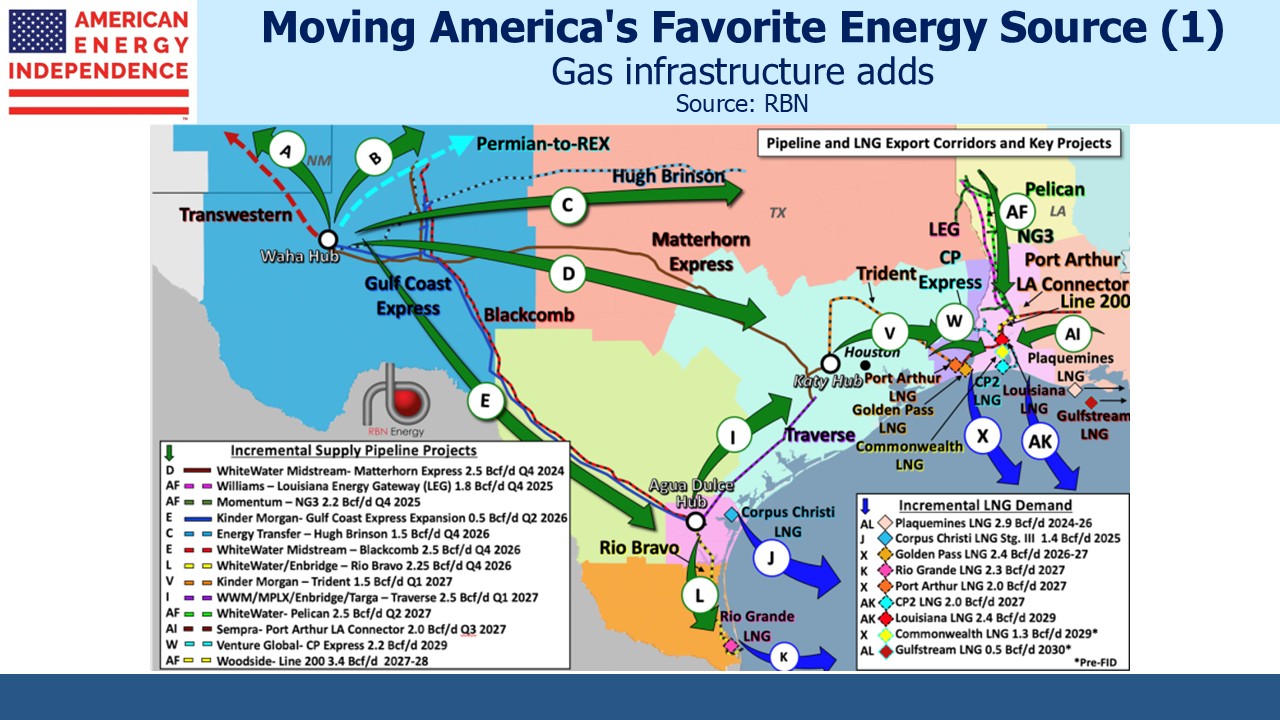

The last few weeks have been challenging for the bullish story on natural gas. On Thursday evening Venture Global (VG) disclosed that they’d lost an arbitration case with BP over their Calcasieu Pass LNG terminal. The International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) found that VG had breached its obligation to make a timely declaration of the start of commercial operations.

BP and other buyers had signed Sale and Purchase Agreements (SPAs) that would start delivering LNG once VG decided the terminal was “operational.” When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, global LNG prices soared as Europe struggled to replace lost pipeline imports of natural gas from Russia.

VG interpreted their agreements as giving them enough latitude to delay fulfilling LNG shipments under their SPAs, which allowed them to sell the LNG the terminal was already producing into the high-priced spot market (see Nothing Ventured, Nothing Gained).

Shell, BP and other expectant recipients of LNG cried foul and took VG to arbitration, claiming that VG’s windfall gains of $3.5BN were rightly theirs. VG plowed the cash back into their business, building the Plaquemines terminal, reducing their reliance on debt markets.

In August, VG won a similar arbitration dispute with Shell, also before the ICC. It’s unclear how the same facts and circumstances were interpreted differently by the same tribunal. It seems arbitration can be arbitrary. Following the August victory, VG not unreasonably said they expected similar outcomes in other cases. In an SEC filing submitted just before the Shell ruling, VG warned of $6.7-7.4BN in exposure if all the arbitration cases were lost.

On Friday, investors reacted to the news by wiping over $7.5BN from VG’s market cap. Assuming the market was 100% sure of positive arbitration outcomes prior, this exceeds the worst case they warned of in August since the Shell ruling was found in their favor. Wells Fargo estimates the worst case including damages of $5.5BN. JPMorgan thinks $4.8BN.

VG is on track to generate over $6.4BN in EBITDA this year, growing by perhaps $300MM next year. If arbitration awards reduce EBITDA by $1BN annually over the next five years, the company is at around 11.8X Enterprise Value/EBITDA. Cheniere is at 12.4X. The ruling was a big surprise and disappointment, but it leaves the stock fully priced for the worst case.

We avoided buying at the January IPO and even after Friday’s collapse, the stock is only modestly below our entry point. Since its IPO VG is –60%.

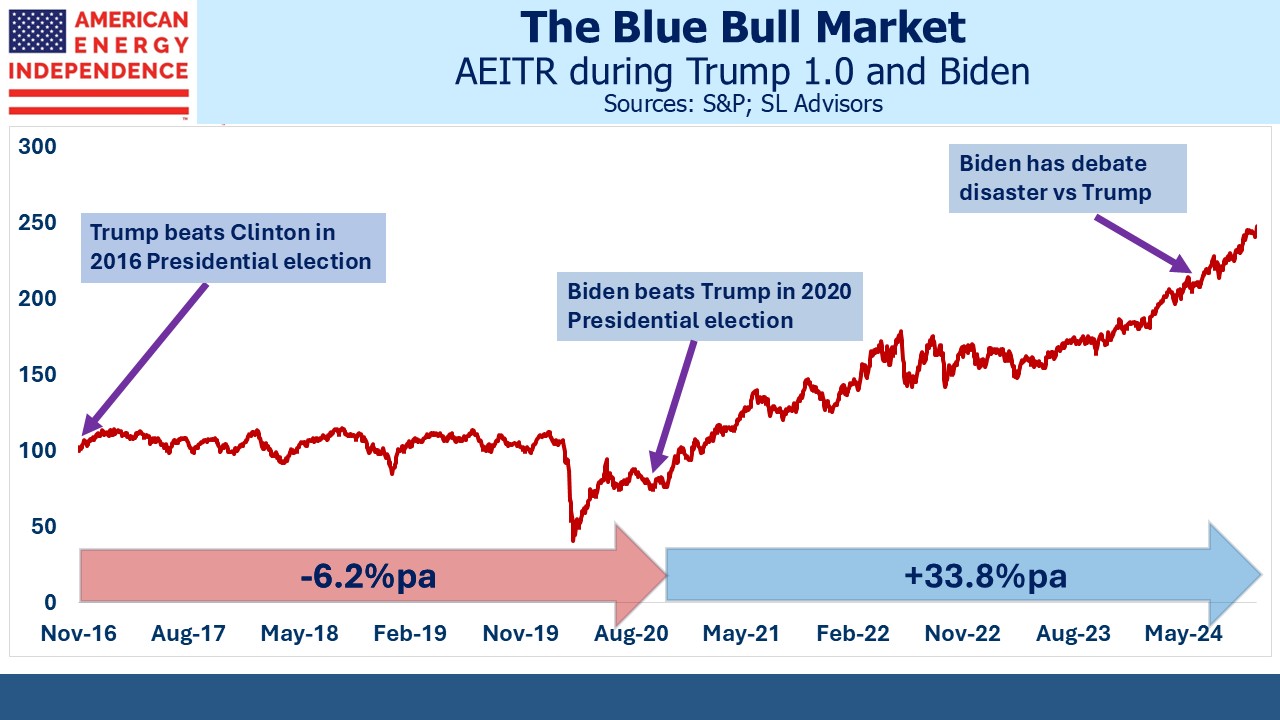

I’m going to be traveling to see clients over the next two weeks. A year ago, at one client’s annual conference, I received applause before even beginning my presentation. Four years of sparkling returns were warmly received, but this year has been tough. This time around I anticipate a friendly but less exuberant welcome.

NextDecade (NEXT), whose Rio Grande LNG terminal should start shipping LNG in 2027, recently lost their CFO, an event that algorithms duly interpreted as a reason to sell. It’s been a volatile stock, losing almost half its value following Liberation Day in April. It recovered in the summer, then swooned again when it announced Final Investment Decision on Train 4 with a modestly lower projected EBITDA.

NEXT doesn’t generate any cash today, but $800MM of Distributable Cash Flow (DCF) in 2030 discounted to today at 15% pa is worth about $400MM, which is a multiple of around 4X on today’s $1.7BN market cap. It looks cheap.

YTD it is -16%.

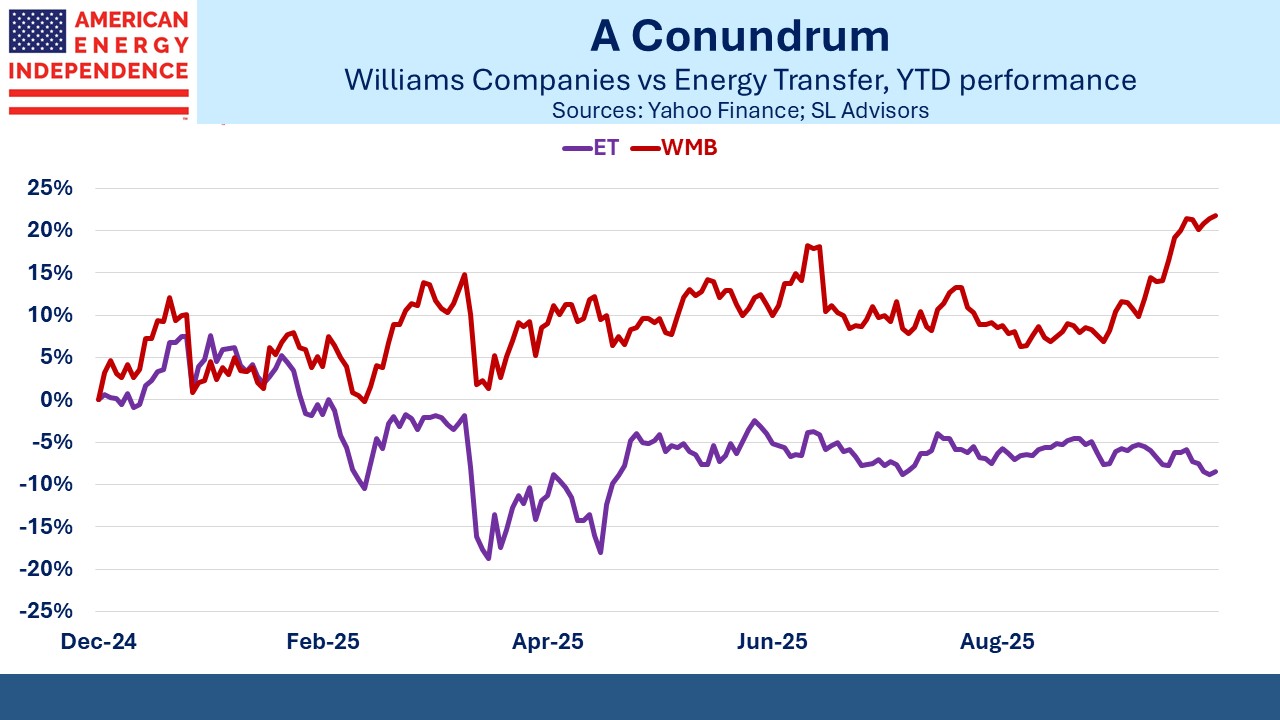

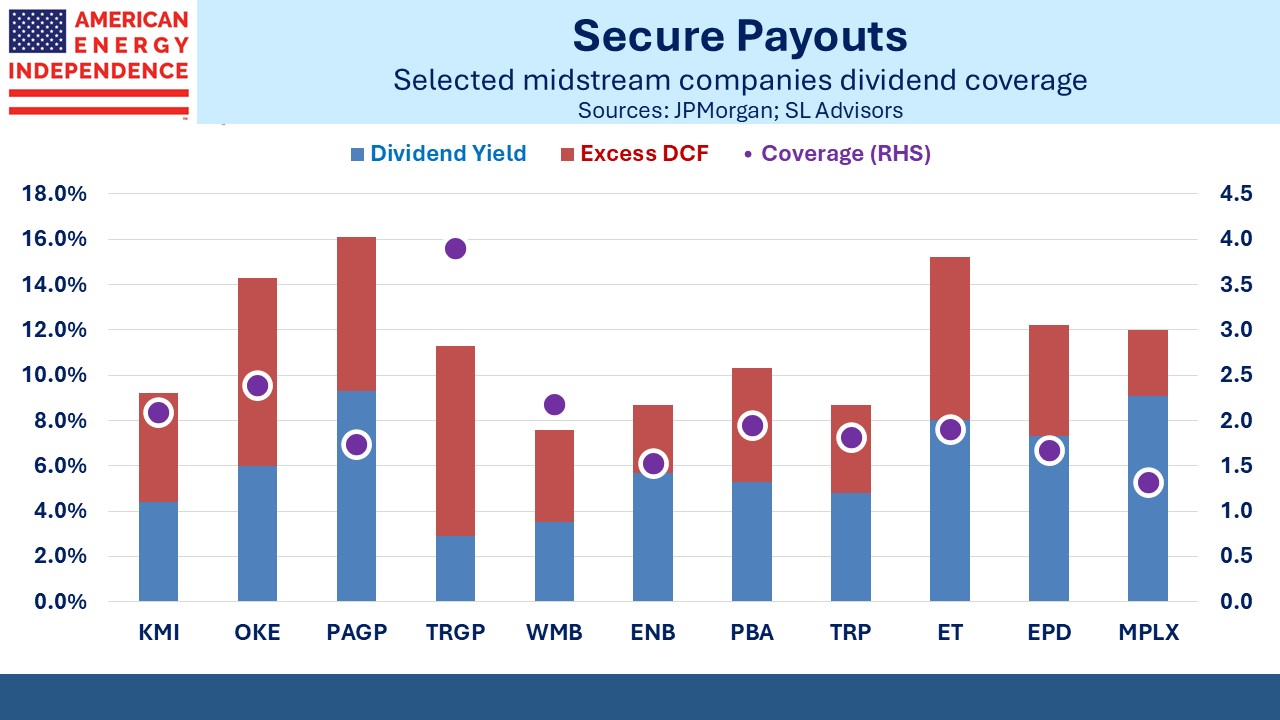

Energy Transfer (ET) has disappointed the many financial advisors we know that own it directly. Its 7.8% distribution yield is almost 2X covered by DCF. YTD it is –12%. It looks attractive to us.

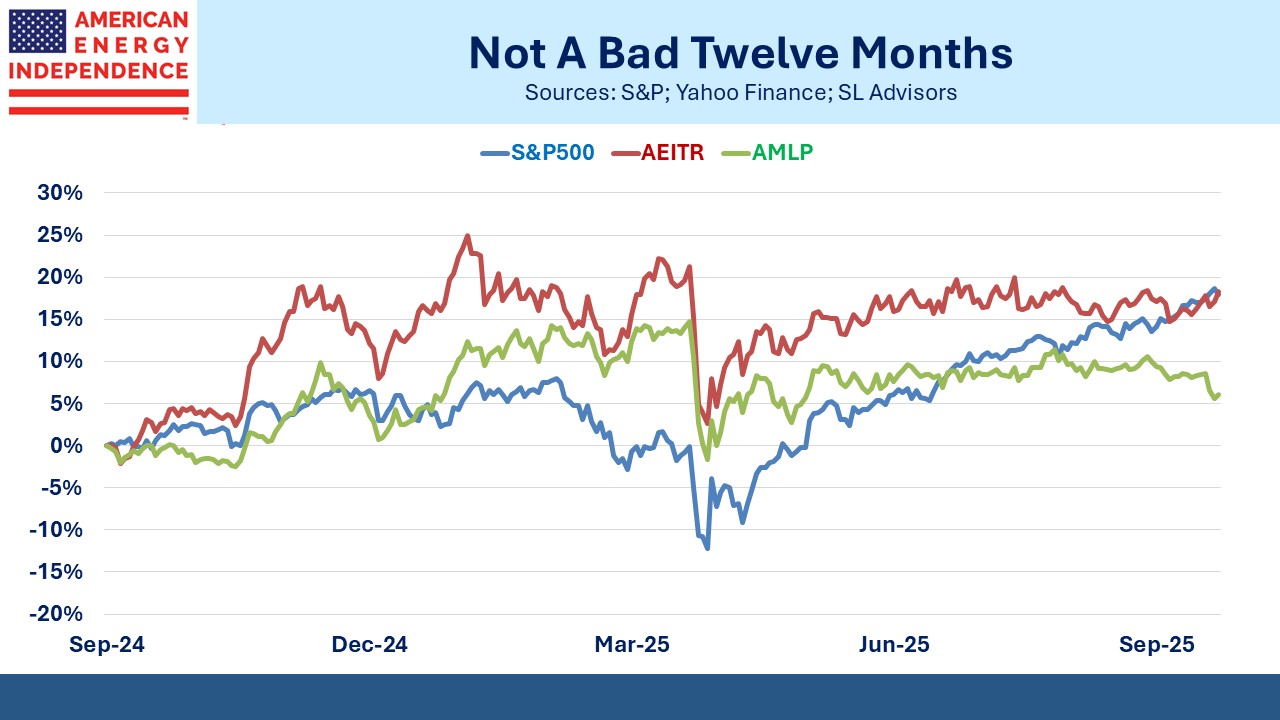

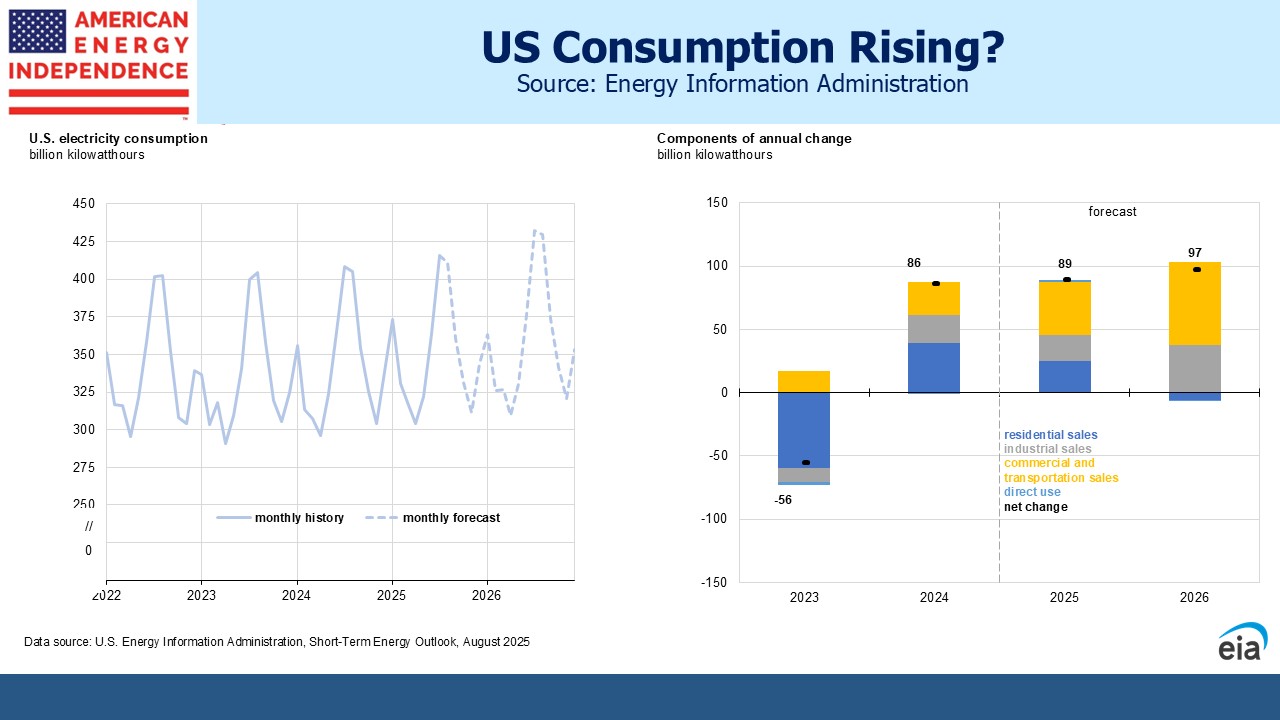

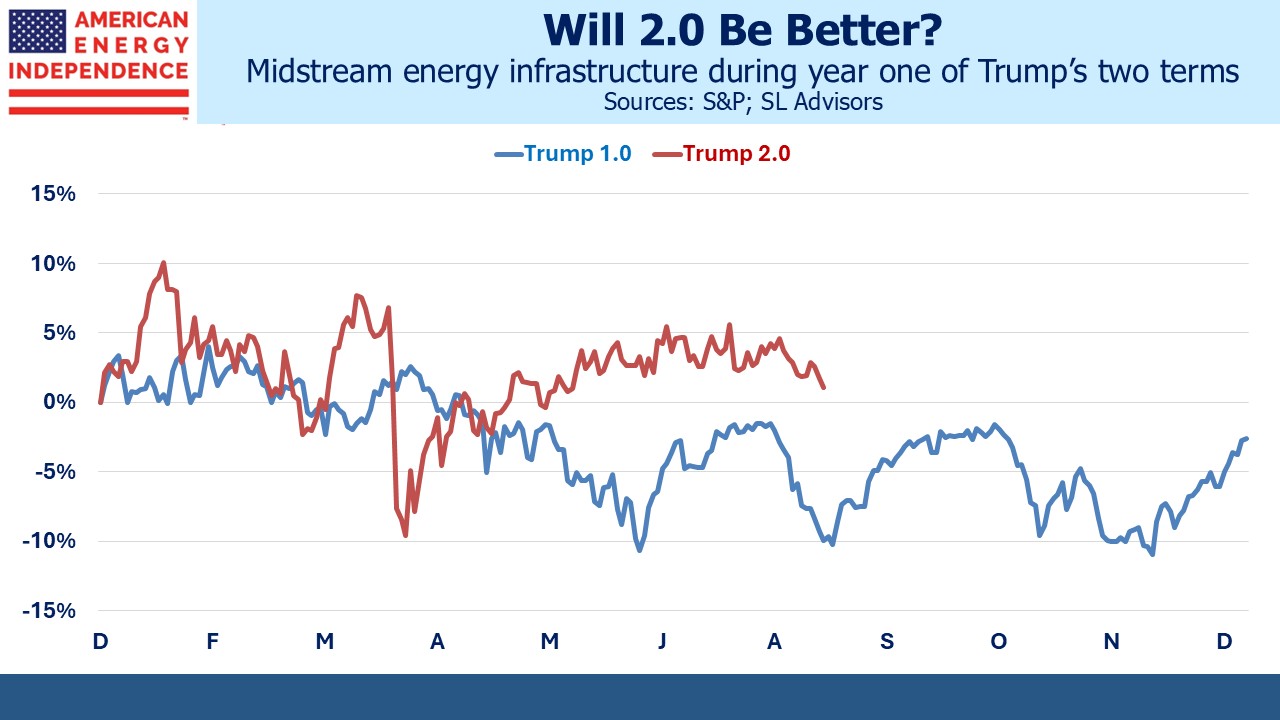

Midstream as defined by the American Energy Independence Index (AEITR) is –1% YTD. Natural gas exposed names have lagged. Gas demand for data centers was last year’s story. Concerns about excess LNG capacity have weighed on exporters this year. The AI-laden S&P500 is +13%.

Over the past twelve months relative performance is better than YTD, but the calendar year is typically how investors assess outcomes.

The possible resumption of a trade war with China dominated Friday’s news. Even Trump’s biggest critics have praised the peace agreement between Israel and Hamas. It looks as if we’re moving from that victory to more capricious “slapping” of tariffs.

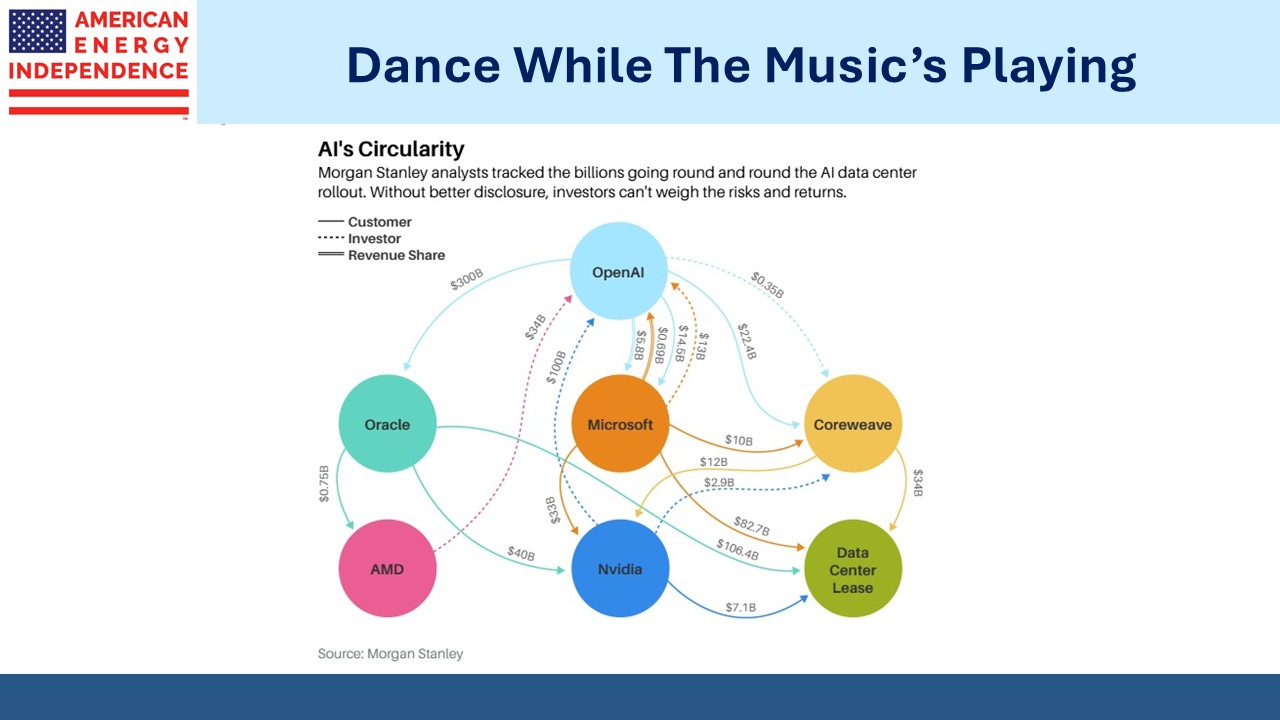

The AI bubble is so commonly referenced that it’s hard to believe anyone is unaware of the circular deals identified by Morgan Stanley. As former Citigroup CEO Chuck Prince memorably said in 2007 shortly before the Great Financial Crisis, “As long as the music’s playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.” You’ll probably see that quote remembered elsewhere before too long.

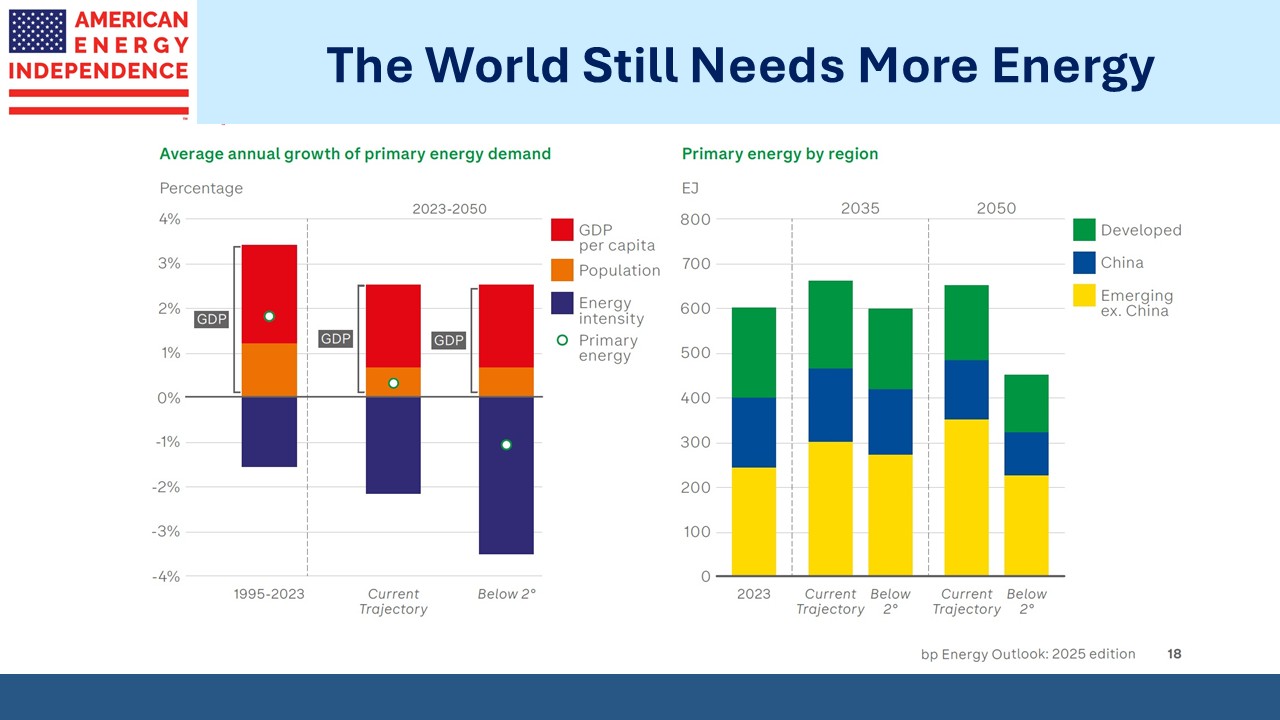

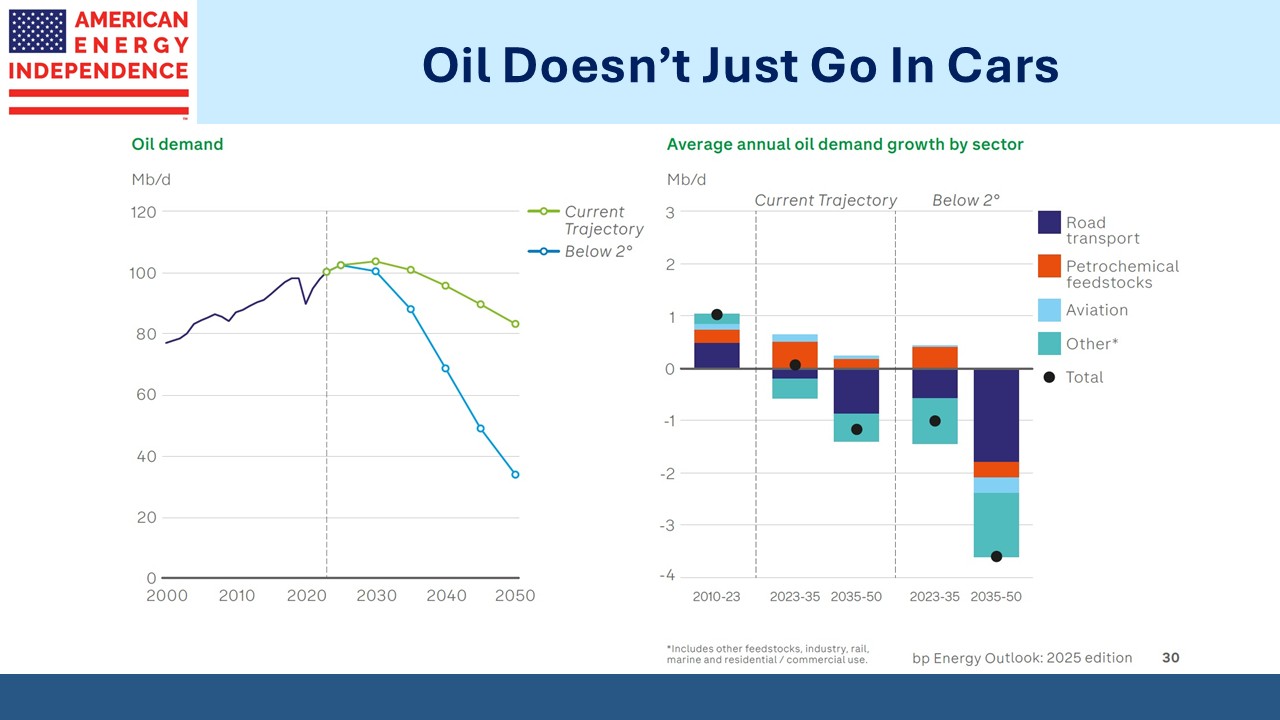

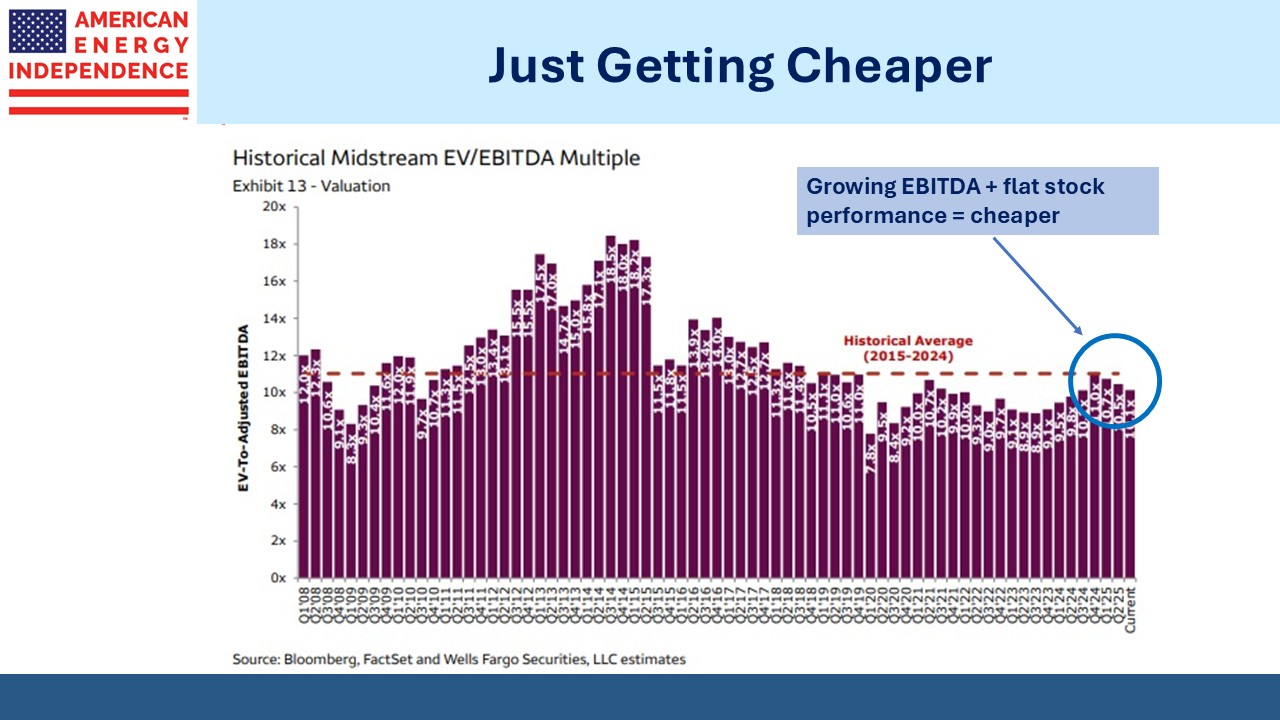

If either or both of these stories cause a further unraveling, midstream infrastructure will still be generating growing cashflows, untarnished by the froth of this year’s market.

We have two have funds that seek to profit from this environment: