Uncle Sam Helps You Short AMLP

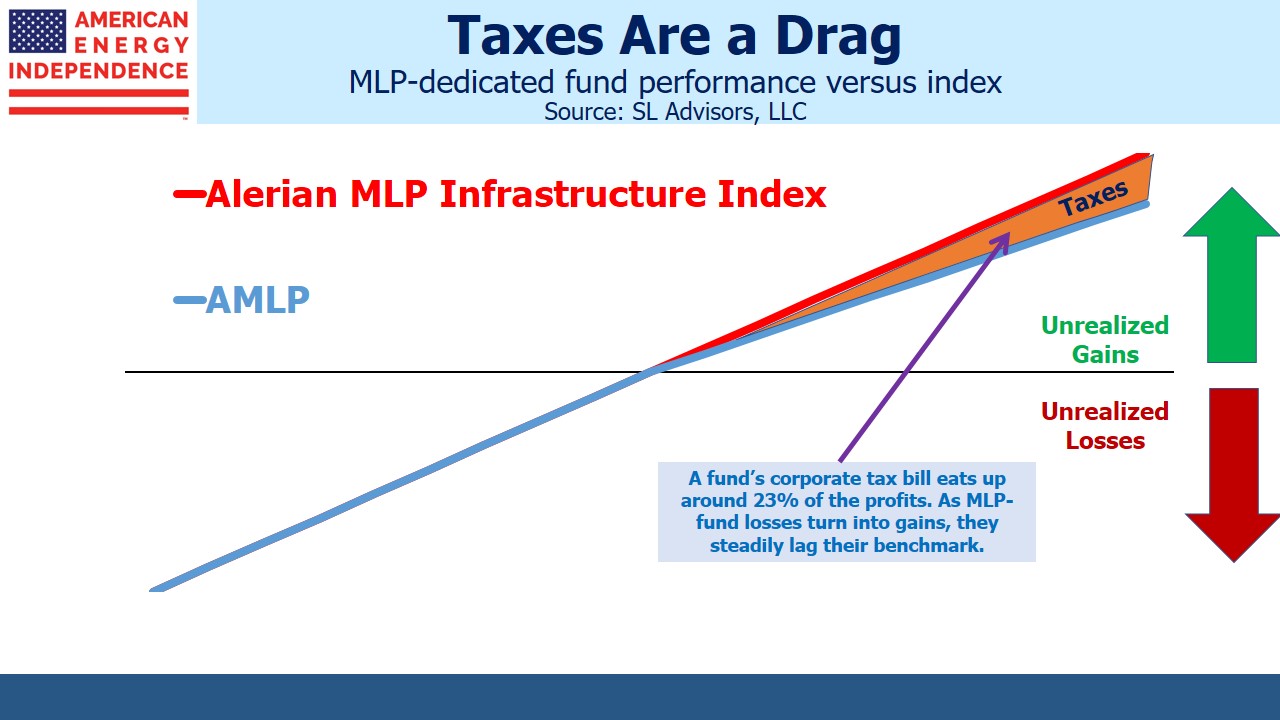

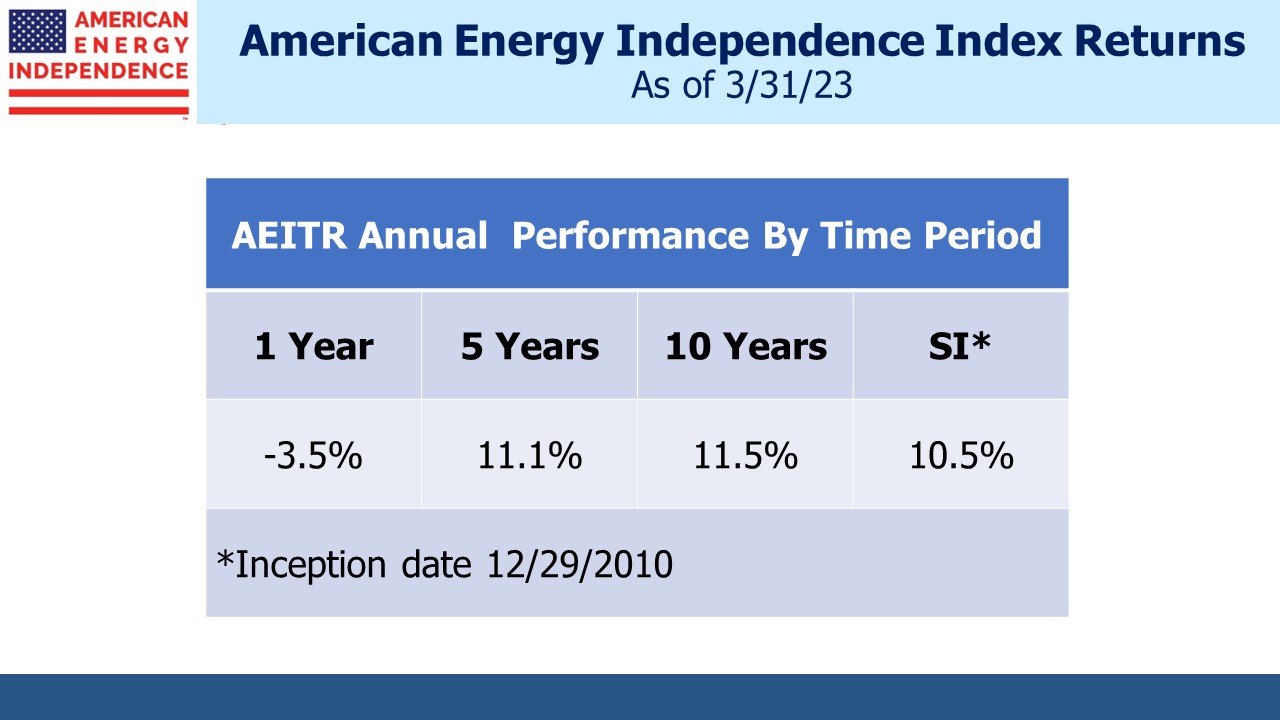

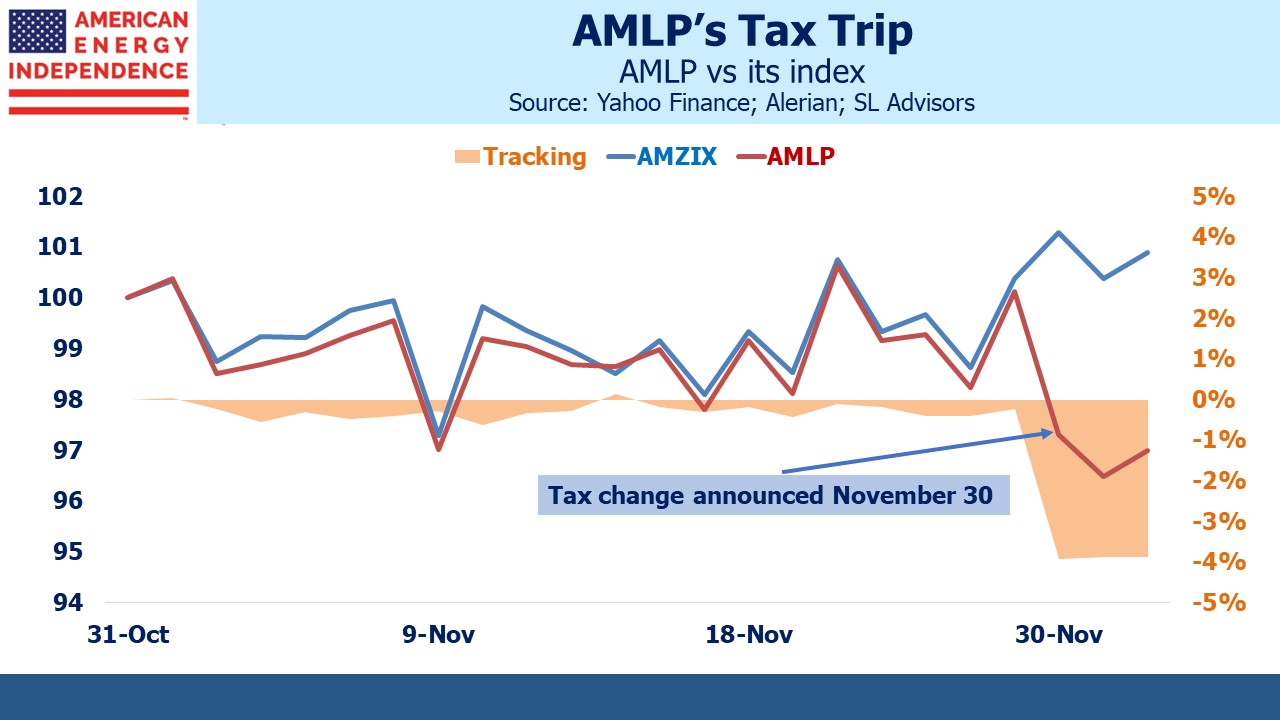

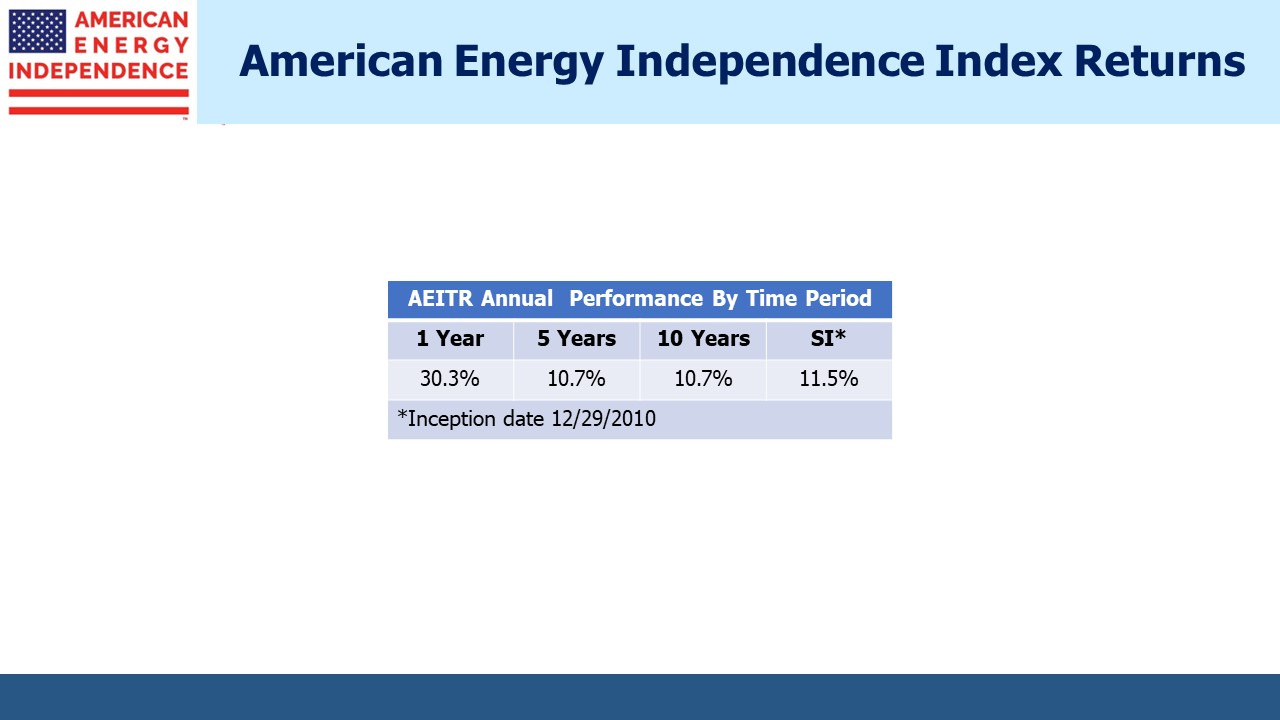

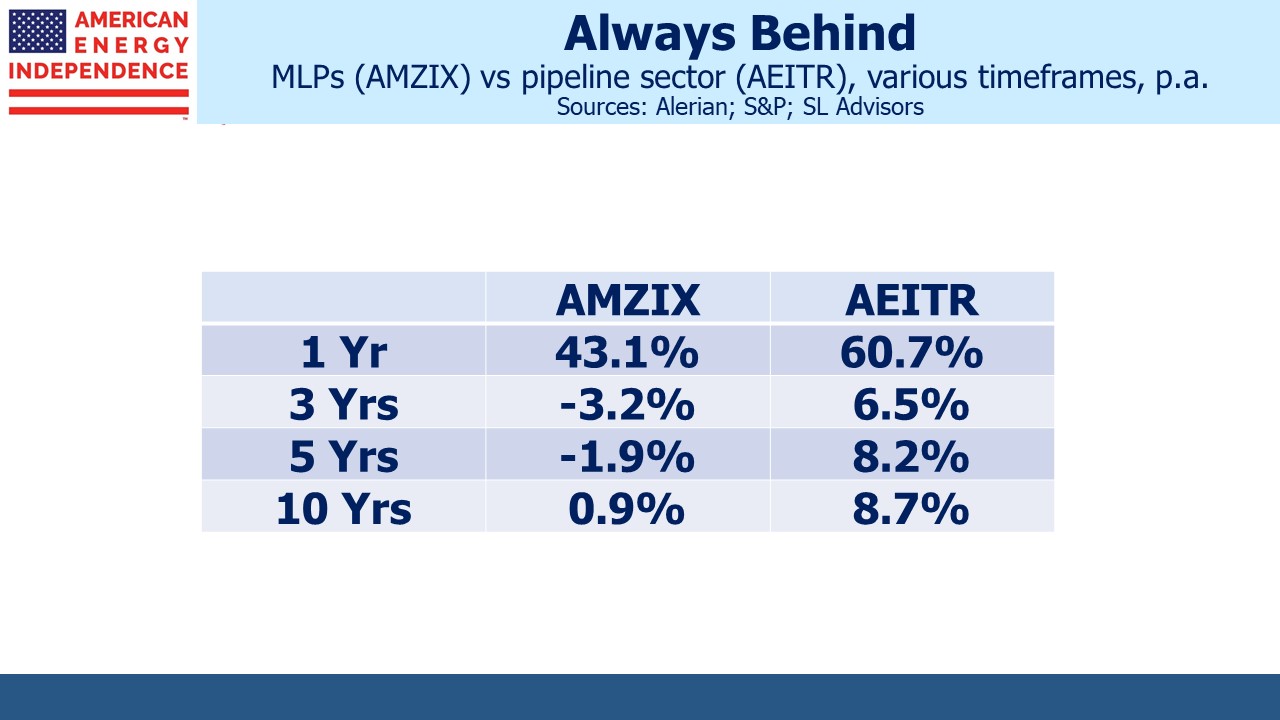

The Alerian MLP ETF (AMLP), with its tax-burdened structure (see AMLP’s Tax Bondage), is by design unable to come close to the return on its benchmark, the Alerian MLP Infrastructure Index (AMZI). Because AMLP doesn’t qualify for treatment as a Regulated Investment Company (RIC), it’s subject to corporate income taxes just like any other corporation. The fund’s tax liability has acted as a substantial drag on returns; since inception in 2010, it has returned just 1.99% (through June 30th), less than half its benchmark of 4.39%.

When AMLP’s portfolio rises, its NAV lags by the amount of the additional tax liability. When its holdings fall, AMLP reduces its taxes owed which cushions the blow somewhat. In fact, the tax drag acts to dampen its volatility. Tax-impaired returns ought not to be that attractive, although occasionally an investor notes that he likes the resulting lower volatility. While MLPs have been choppy in recent years, embracing this type of tax-encumbered, reduced price movement seems wrongheaded; after all, AMLP holders presumably expect a positive return, and the tax structure lowers it.

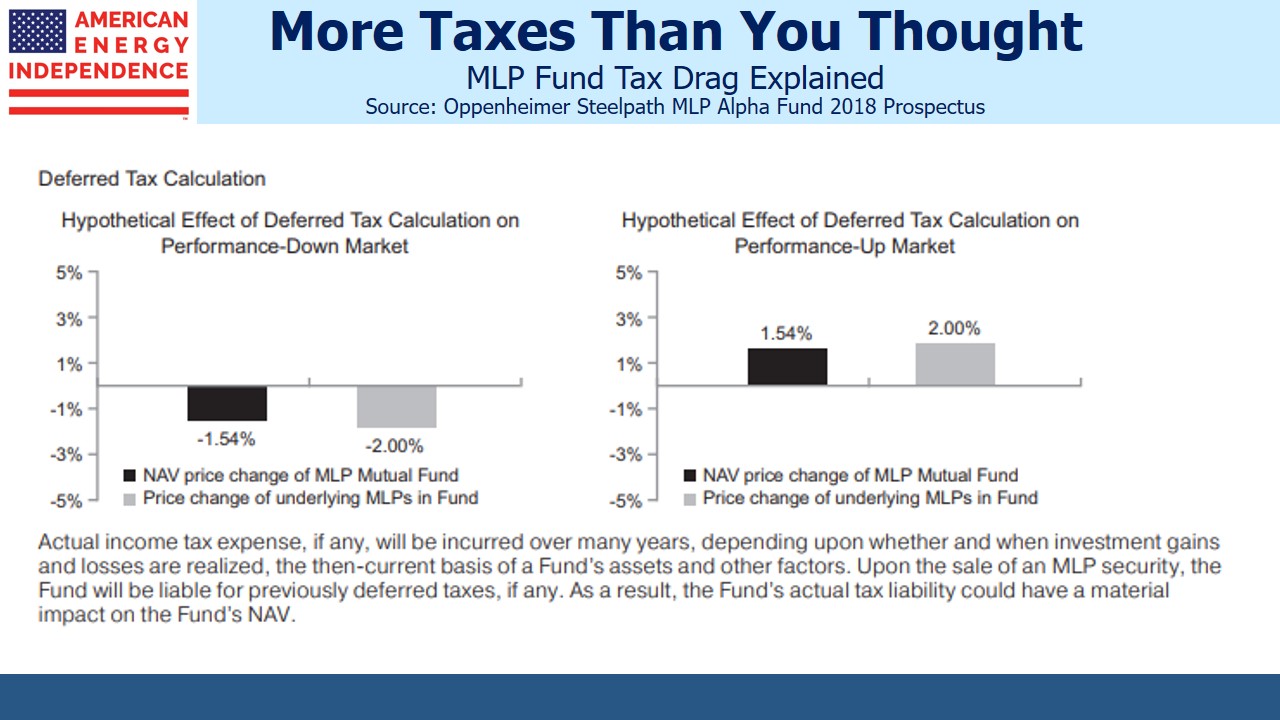

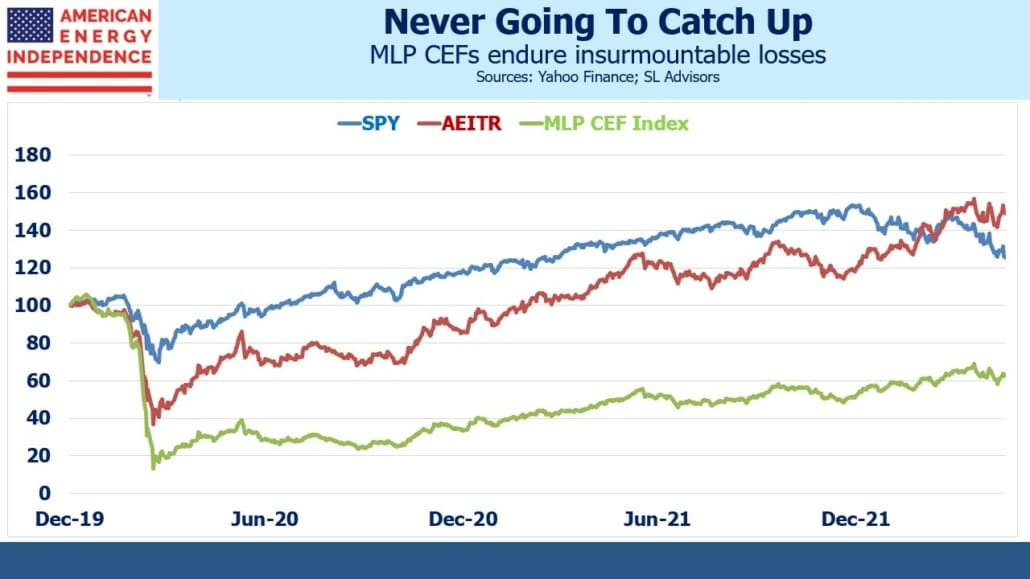

AMLP is simply the biggest of around $50BN in flawed funds. The chart below is from an Oppenheimer prospectus which helpfully explains how taxes hurt returns on their funds.

.avia-image-container.av-46wqn4-5ff82a133333ab5af23ae337652e062c img.avia_image{ box-shadow:none; } .avia-image-container.av-46wqn4-5ff82a133333ab5af23ae337652e062c .av-image-caption-overlay-center{ color:#ffffff; }

In an additional wrinkle to the pay-off profile, taxes only accrue when AMLP has unrealized gains. In such cases it holds a Deferred Tax Liability (DTL). When it has unrealized losses, as currently, it doesn’t accrue a tax loss carryforward, or Deferred Tax Asset (DTA). At such times the tax-induced low volatility disappears, and AMLP moves up and down with the market.

.avia-image-container.av-26c7ps-b393e982f1fd97dca9b32d1465a42963 img.avia_image{ box-shadow:none; } .avia-image-container.av-26c7ps-b393e982f1fd97dca9b32d1465a42963 .av-image-caption-overlay-center{ color:#ffffff; }

We are approaching an inflection point. AMLP’s unrealized losses are shrinking as the sector grinds higher. Its current DTA (which is offset with a valuation allowance, thus negating it) will flip to a DTL with the next 4-5% rise in its portfolio. At that point, further gains will trigger taxes owed. Its modestly lower volatility will return. With an approximate tax rate of 23%, AMLP will provide its holders with only 77% of the upside or all of the downside.

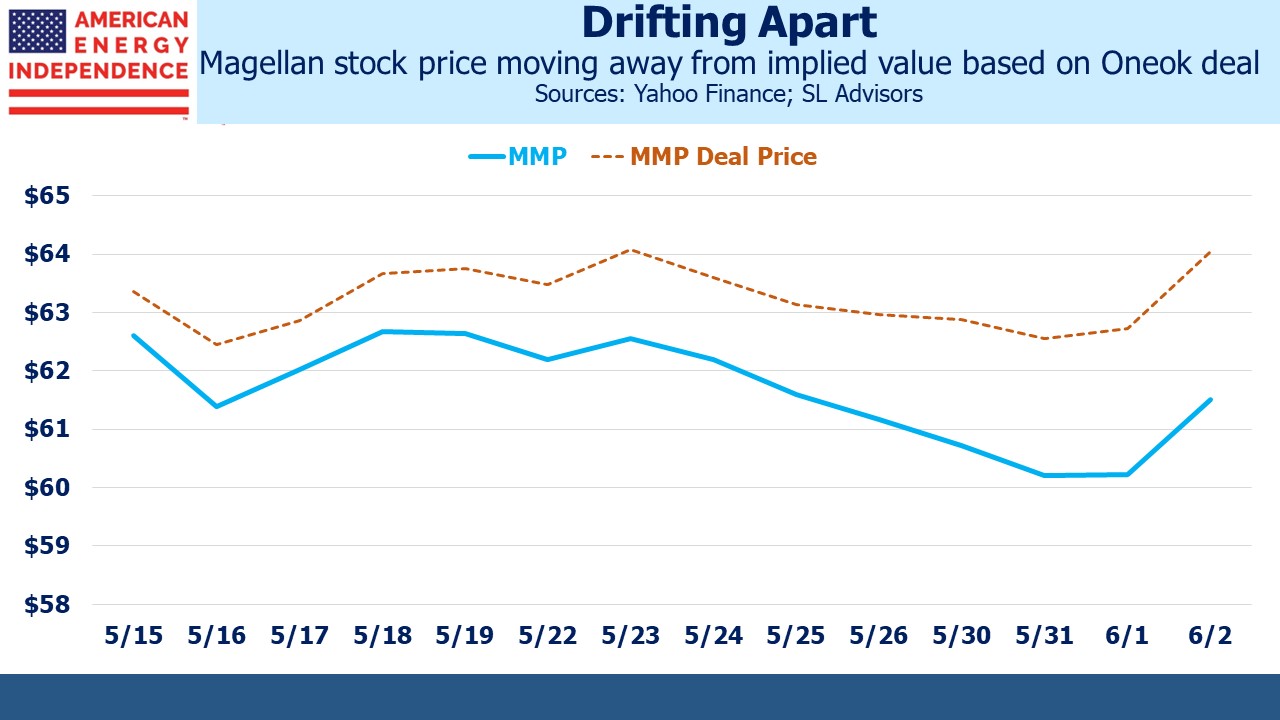

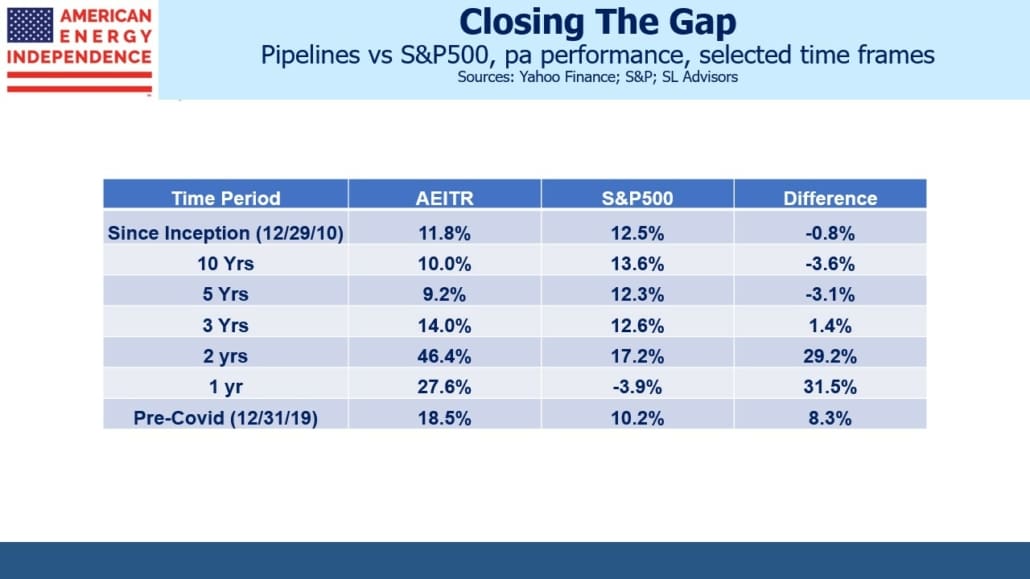

Like the approach of a surfer’s perfect wave, this situation offers the AMLP short-seller a rare, asymmetric opportunity. Just as an AMLP holder is accepting diminished upside for full downside risk, the AMLP short will enjoy the complete benefit on the downside with constrained losses on the upside. Combining a short AMLP with a diversified long position in energy infrastructure names or a properly structured, RIC-compliant, non-tax-burdened fund creates an interesting trading opportunity.

Such a long/short portfolio should be profitable in a rising market and roughly breakeven in a down market. There are financing costs, but AMLP has $10BN outstanding and so is not that hard to borrow.

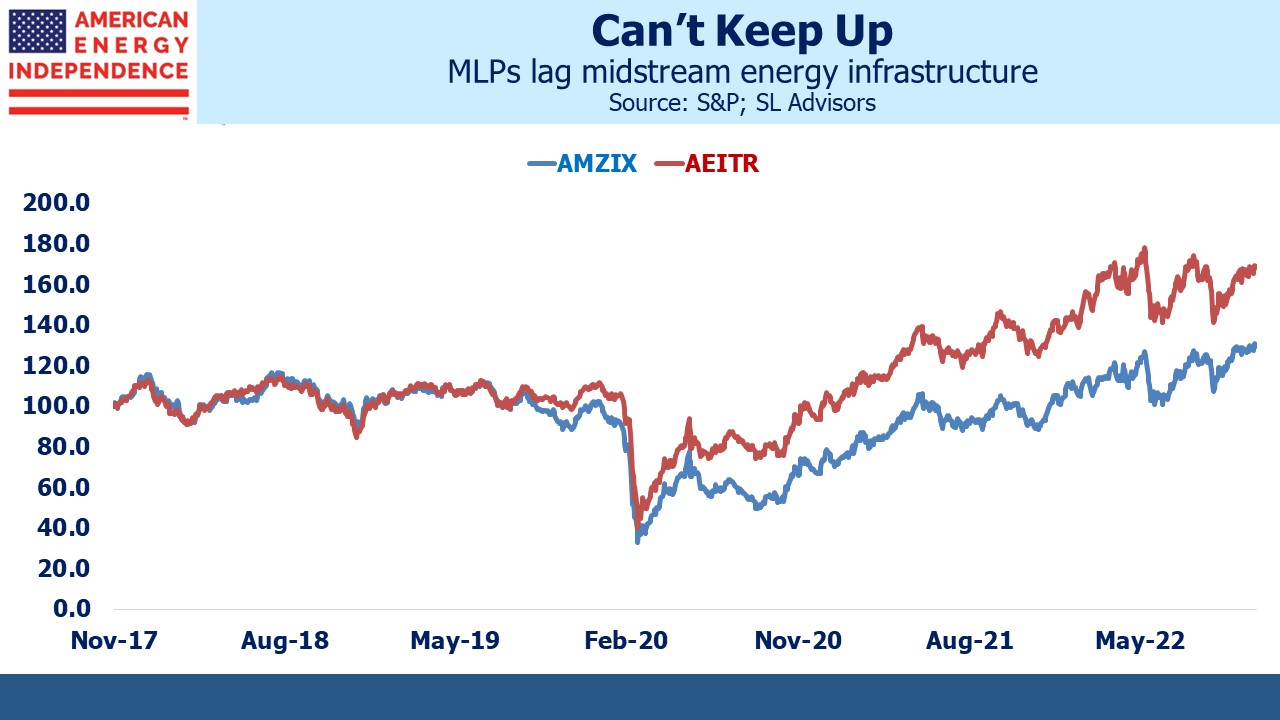

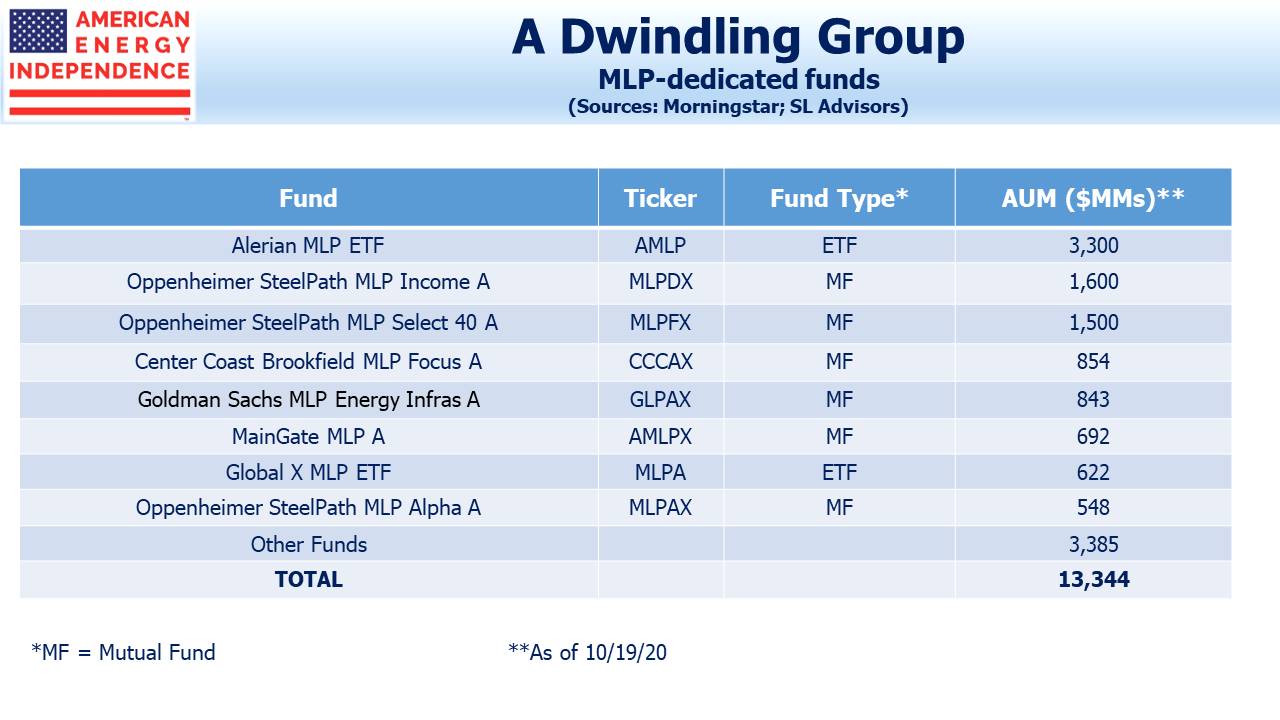

Because AMLP is 100% invested in MLPs, a diversified long portfolio that includes energy infrastructure corporations further allows the investor to bet on a continued shrinking of MLPs as a subsector of energy infrastructure. As the biggest MLPs convert to corporations where they can access a far bigger set of buyers, this leaves fewer names with a lower median market cap (see Are MLPs Going Away?). MLP fund investors face the additional risk that one of the larger funds elects to drop the tax burden by selling 75% of its MLPs, becoming RIC-compliant. This could depress MLPs and hurt valuations of all MLP-dedicated funds.

This kind of asymmetry has value. Option premiums reflect the substantial upside/downside difference for the holder. Long-dated bonds (most dramatically, zero-coupon bonds) also offer a modest amount of asymmetry due to convexity, which causes investors to drive their yields somewhat lower than they’d otherwise be. In theory, AMLP should trade at a discount to NAV because of its tax-driven asymmetry, reducing the benefits of shorting and providing some additional return to holders to compensate for its flawed structure. Because the AMLP short is receiving the benefit of the tax drag, it’s one of the few ways you can really get Uncle Sam to work for you.

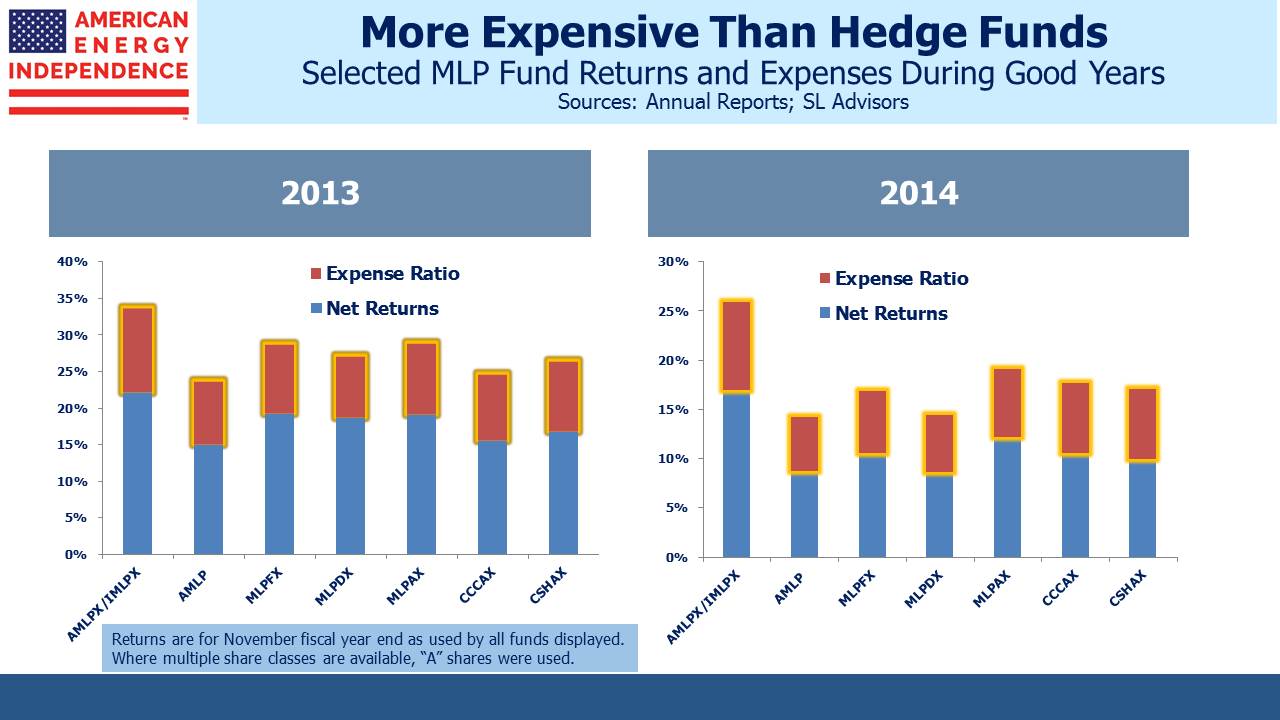

The benefits of shorting AMLP highlight the diminished return prospects of the holders. There are several other similarly tax-impaired funds, including mutual fund products from Oppenheimer SteelPath, Cushing Mainstay and Goldman Sachs, and a couple of small ETFs. While none of these are short candidates, they all suffer from the same structural flaws as AMLP. Their holders are unlikely to enjoy returns close to the indices, even while they incur unimpeded downside risk.

MLP-dedicated funds are unique in owing taxes at the fund level. Fund investors seeking energy infrastructure exposure should select a RIC-compliant, non-tax paying fund with less than 25% in MLPs.

We are short AMLP.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment: