Incoherent Energy Policies

Recently Chevron’s CEO Mike Wirth gave an interview in the Financial Times where he explained why blame for the current energy crunch lies squarely with western governments and the poorly conceived policies they have followed. To varying degrees they have assumed a painless pivot away from fossil fuels before alternative sources are ready. Germany and California are the best examples of this.

But New England’s grid operator, ISO New England Inc., has also warned of “rolling blackouts” if an unusually cold winter places too much strain on generation. The region is having to compete with European buyers of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG), because they’ve blocked new natural gas pipelines that would allow access to some of the world’s cheapest gas in Pennsylvania. ISO has tried to tap into hydropower from Quebec, but New Hampshire refuses to allow the construction of transmission lines. Environmental extremists may be passionate, but their efforts are hardly synchronized.

Mike Wirth said that The Biden administration had entered office with a “very clear agenda . . . to make it more difficult for our industry to deliver energy to our customers”.

“If people want to stop driving, stop flying . . . that’s a choice for society,” Wirth added. “I don’t think most people want to move backwards in terms of their quality of their life . . . our products enable that.” He dismissed the White House response to the energy crisis as “all tactical.”

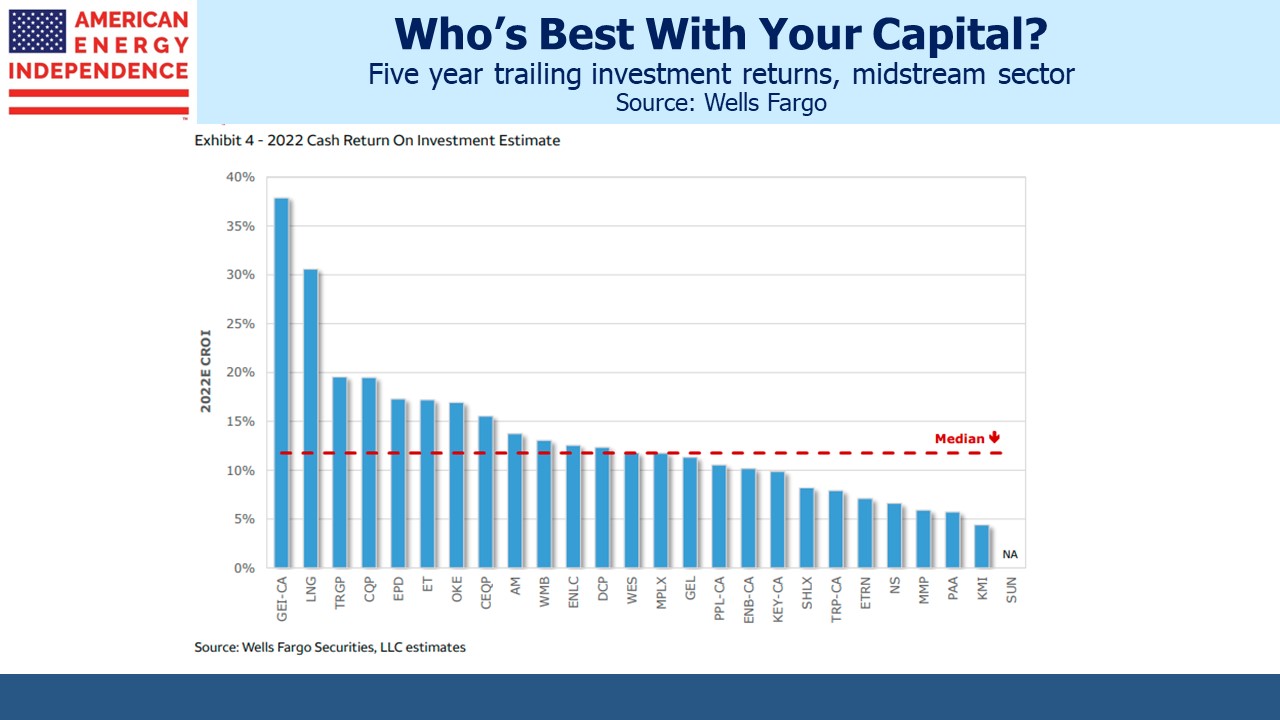

Energy companies have responded to poorly conceived policies by spending less. This has improved returns for investors. Wells Fargo produced a detailed analysis showing Returns On Invested Capital (ROIC) by company and time period for midstream energy infrastructure. The 2017 five year trailing median ROIC for companies in the sector was 8.6%, reflecting in some cases overbuilding of capacity. They estimate the median trailing ROIC will have improved to 11.8% by year’s end.

These improved metrics show the result of improved capital discipline.

Returns vary widely. Cheniere is expected to exceed 30%, an extraordinary result for such a big company. Targa Resources, recently added to the S&P500, is a high performer along with widely respected Enterprise Products Partners and the perennial favorite of many financial advisors, Energy Transfer.

Kinder Morgan has a poor record of investment returns, something we raised with them directly in early 2020, just before Covid overwhelmed any thoughtful investment analysis (see Kinder Morgan’s Slick Numeracy and Kinder Morgan Responds to our Recent Criticism).

Plains All American is another laggard. They overbuilt crude pipeline capacity out of the Permian in west Texas.

Investor returns are generated when companies’ ROIC exceeds their Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). Wells Fargo finds that the median spread between the two was 2.3% for the five years through 2021, a figure that will likely exceed 2.5% this year. Crestwood Partners is the big winner on this scale with a trailing five-year ROIC of 58.8% and a spread over their WACC of 46.7%. However, they’re expected to drop to a more pedestrian 15% ROIC this year. Cheniere achieved a spread of 10.9% for their MLP and 9.7% at the parent c-corp. Laggards include Kinder Morgan and Plains All American, with a negative spread between ROIC and WACC of –4.4% and –12.4% respectively.

These figures are driving the strong relative performance of the pipeline sector. They represent the tangible result of more selective allocation of capital to new projects. Although we often flippantly acknowledge the assistance climate extremists have provided by blocking most new infrastructure, investors also tired of the overbuild that characterized too much of the shale revolution. Oilmen have in their DNA a desire to drill holes – sometimes this rubs off on their midstream cousins. The current fashion for parsimonious capital allocation is working out well.

I’ve spent the past couple of days seeing clients in New Orleans and in the Florida panhandle. Energy investing comes naturally in this part of the country. Everyone I met (admittedly not a random sample) agreed that the Administration’s energy policies are poorly conceived. My common refrain, “Drive a climate protester to their next protest” was well received.

I met one investor who showed me returns from a series of natural gas partnerships made annually over the past six years. The most seasoned of these is generating returns of 120% pa, thanks to appreciating natural gas prices. The US has many institutional advantages that meant the shale revolution could only happen here. Least appreciated is the private ownership of mineral rights, which Americans take for granted but is unique as far as we know.

Britain is more typical, where property ownership extends down a few feet at which point the government takes over. Shale rock formations that hold hydrocarbons are not unique to the US. Poland, the UK, Argentina and China all have potentially accessible reserves, but their exploitation is held up by lack of nearby water (China), numerous small landowners which complicate negotiations (Poland) or poor access to capital (Argentina). In the UK, political opposition brought one effort to a halt as locals complained about the endless trucks and earth tremors while climate extremists argued for 18th century lifestyles.

Now that energy security is superseding the energy transition, the UK government is revisiting opposition to fracking. On energy security the US is way ahead, in spite of incoherent public policies.