Will We Use More Hydrogen?

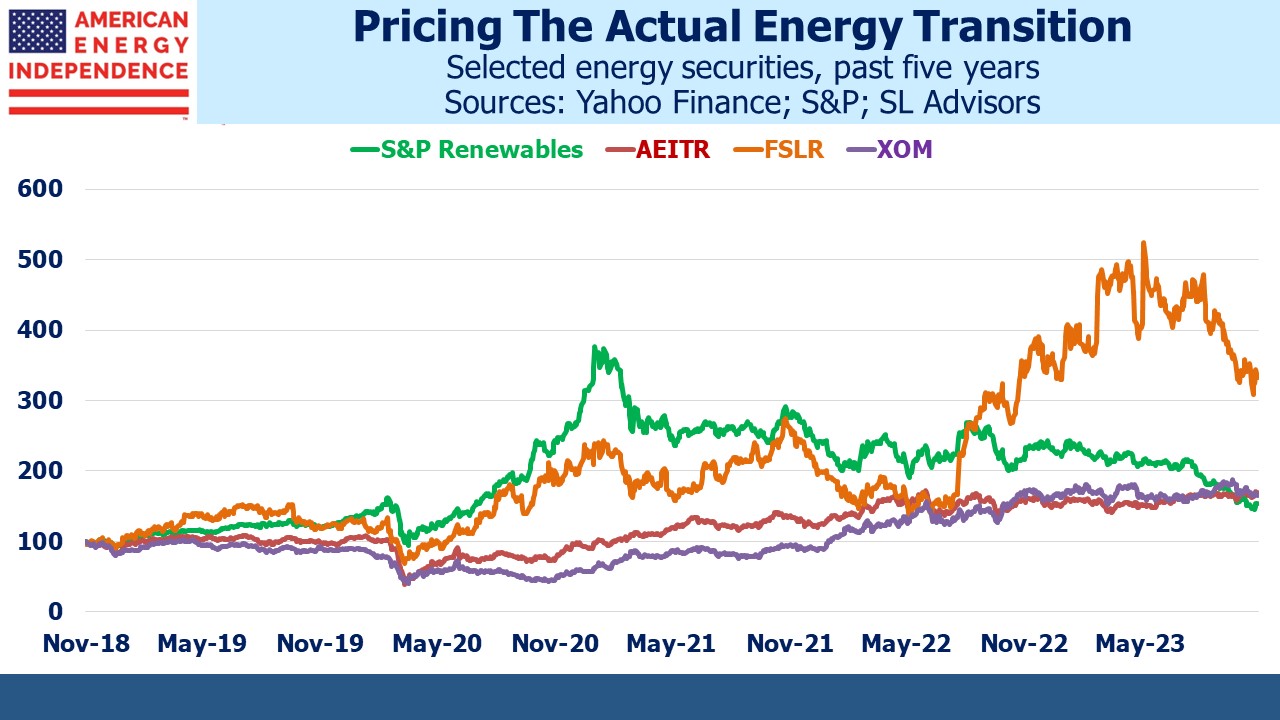

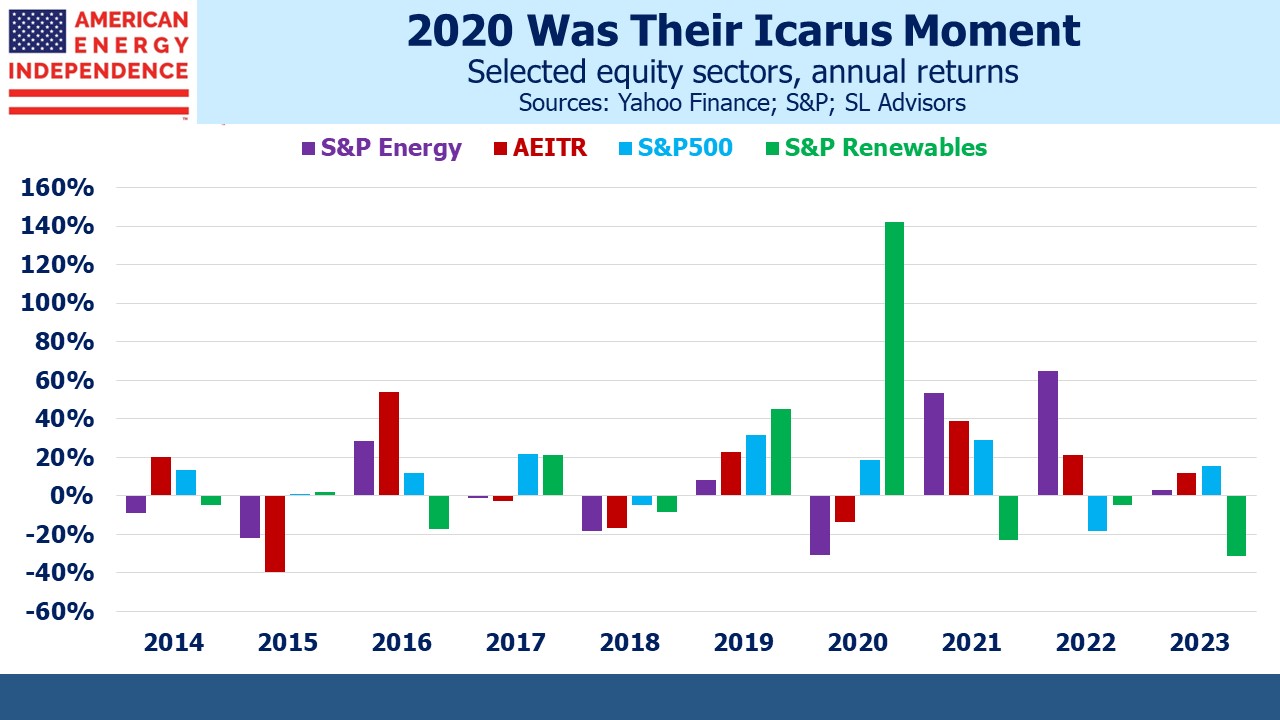

Investors often ask what are the prospects for hydrogen as an energy source. In spite of Jeff Sommer’s conclusion that the market doesn’t think much about the future (see Priced For A Pragmatic Energy Transition) we think about it all the time.

Hydrogen is appealing because when it burns it combines with oxygen to release harmless water vapor. There’s no CO2. There’s a place for hydrogen in industries such as steel and cement where production requires fossil fuels – although electric arc furnaces are increasingly used for certain types of steel, and 43% of planned new capacity will use this method. Currently steel production generates 7-9% of CO2 emissions.

Hydrogen is difficult to handle and expensive to produce. Prolonged contact with steel tends to make the pipeline and welds brittle. Hydrogen molecules are small enough to permeate the steel itself, which over time can cause leaks. Solutions include building pipelines with fiber reinforced polymer, and also blending it in with natural gas to run (up to 15% hydrogen) through our existing pipeline network. Since hydrogen has about one third the energy density of methane (natural gas), delivering the same energy content with a hydrogen blend requires the pipeline to operate at higher pressure, which may require modifications to the pipeline. There are currently 39 pilot projects across the US exploring the hydrogen/methane blend for natural gas distribution. Dominion Energy’s plant in Utah is an example.

There are currently around 1,600 miles of hydrogen pipeline in the US. For reference, we have 305,000 miles of natural gas transmission lines with a further 2.2 million miles of distribution pipes to customers.

Air Products, Linde and Air Liquide produce most of the US’s 10 million tons per annum (MTpa) of hydrogen. It’s produced via Steam Methane Reforming (SMR), which reacts methane with steam at high temperature, producing hydrogen and carbon monoxide, which then combines with oxygen and is released as CO2. If the CO2 is captured this is called Blue hydrogen.

Although hydrogen burns cleanly, its current production requires more energy than the resulting hydrogen contains and generates emissions.

The US recently awarded $7BN in grants to help fund hydrogen hubs that will produce green hydrogen. This will be produced via electrolysis that separates hydrogen from water, and if the power is derived from renewables there are no emissions. The aim is to produce 10 MTpa, (ie double what we do now) by 2030. This is equivalent to around 3 Billion Cubic Feet per Day (BCF/D) of natural gas on an energy equivalent basis, roughly 3% of US production. If this was all blended into our natural gas supply, we’d theoretically reduce emissions from burning natural gas by 3%.

Cleveland Cliffs has tested using hydrogen in steel production and is planning to use some of the green hydrogen that will be produced from one of the aforementioned hydrogen hubs.

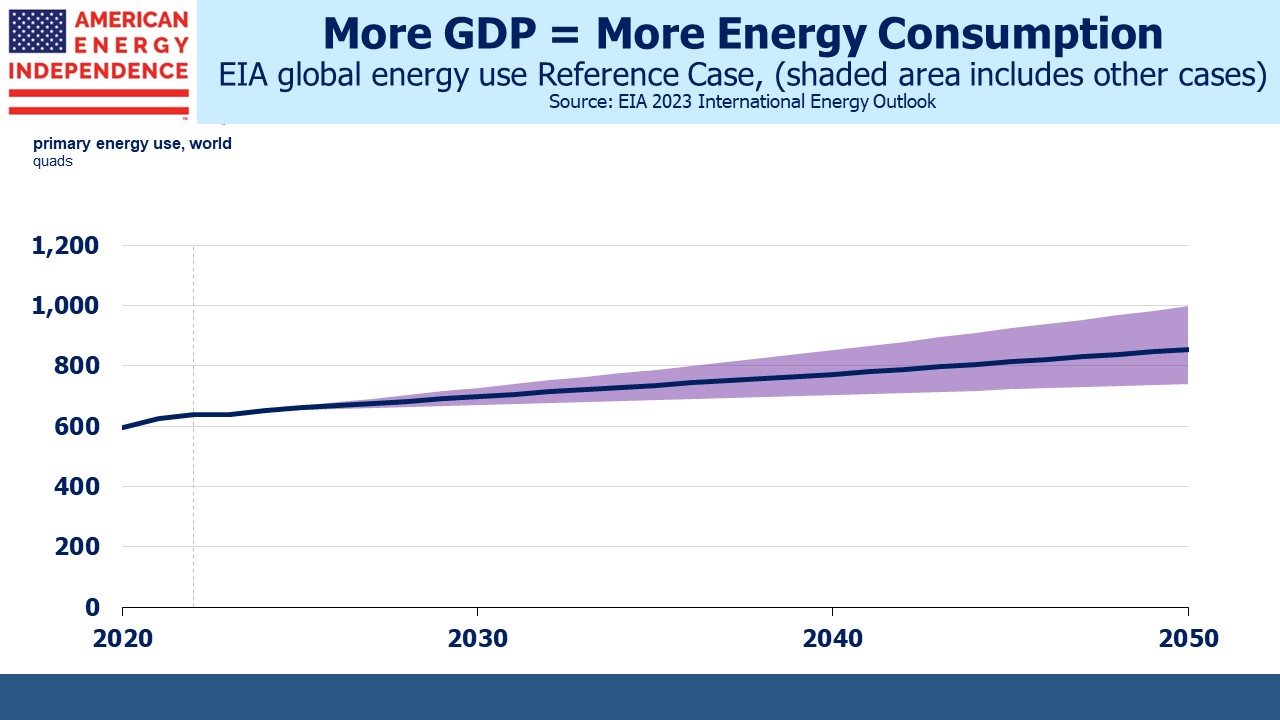

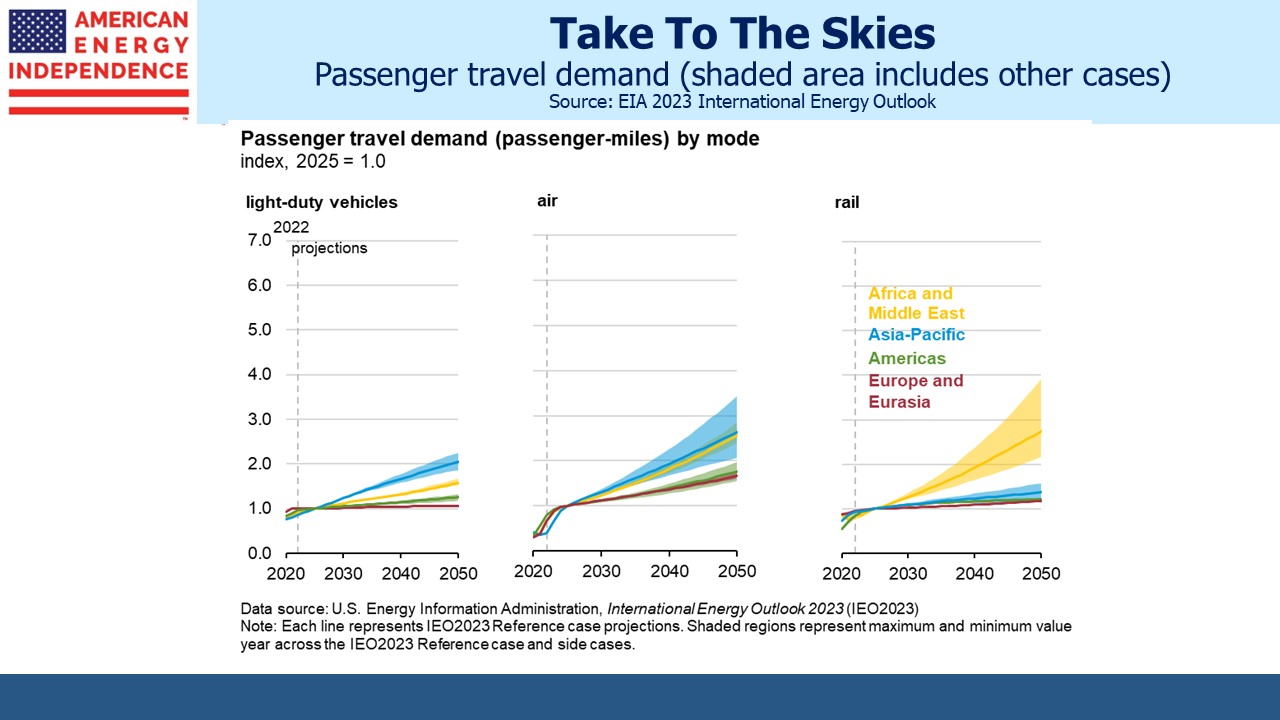

The world uses fossil fuels for around 80% of our primary energy because they’re convenient and not subject to interruption from cloudy or calm days like renewables. They’re dispatchable, as is hydrogen, meaning they’re available whenever needed. Directing the electricity from solar panels and windmills towards the production of green hydrogen seems to me a better use than connecting them to customers via the grid, because the intermittency won’t matter much.

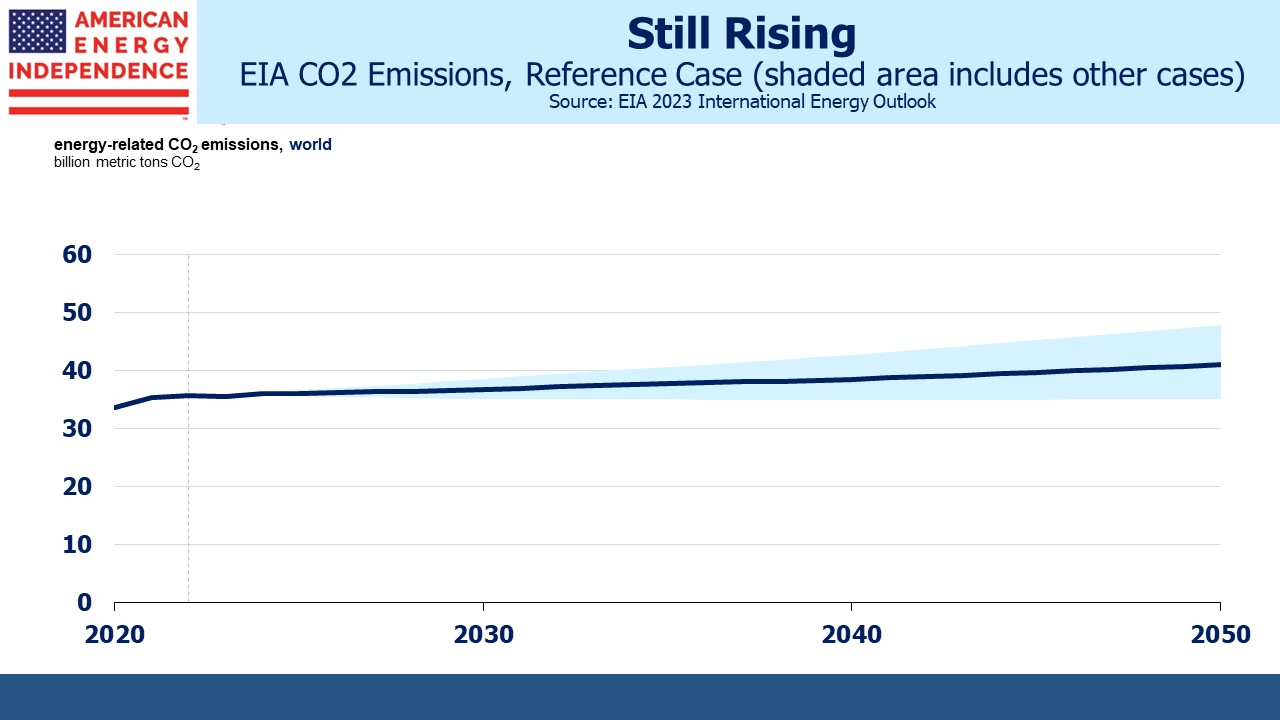

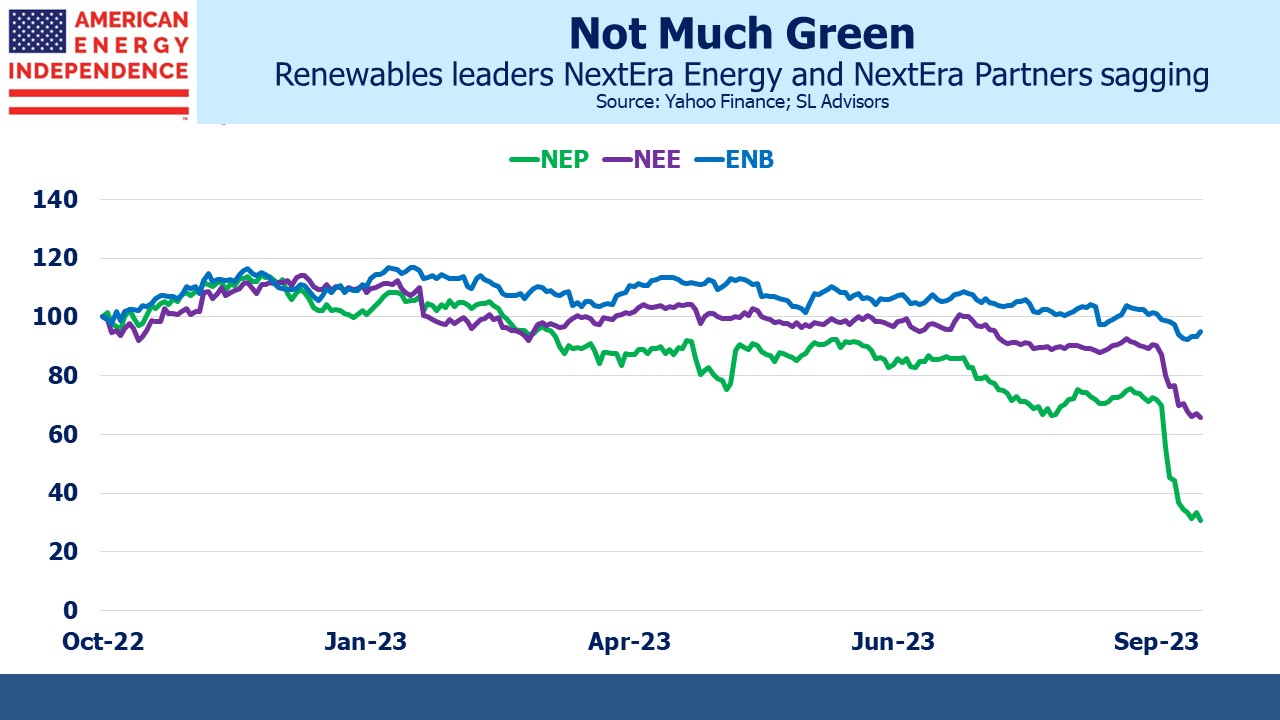

Cost estimates of hydrogen vary widely, but on an energy-equivalent basis green hydrogen is 5-10X the cost of US natural gas. As is often the case with the energy transition, it’s technically possible to reduce emissions but expensive. Climate extremists and liberal politicians continue to assert that renewables are cheaper – meanwhile fossil fuel use keeps growing, as if the world is stubbornly denying itself the opportunity to get more energy for less.

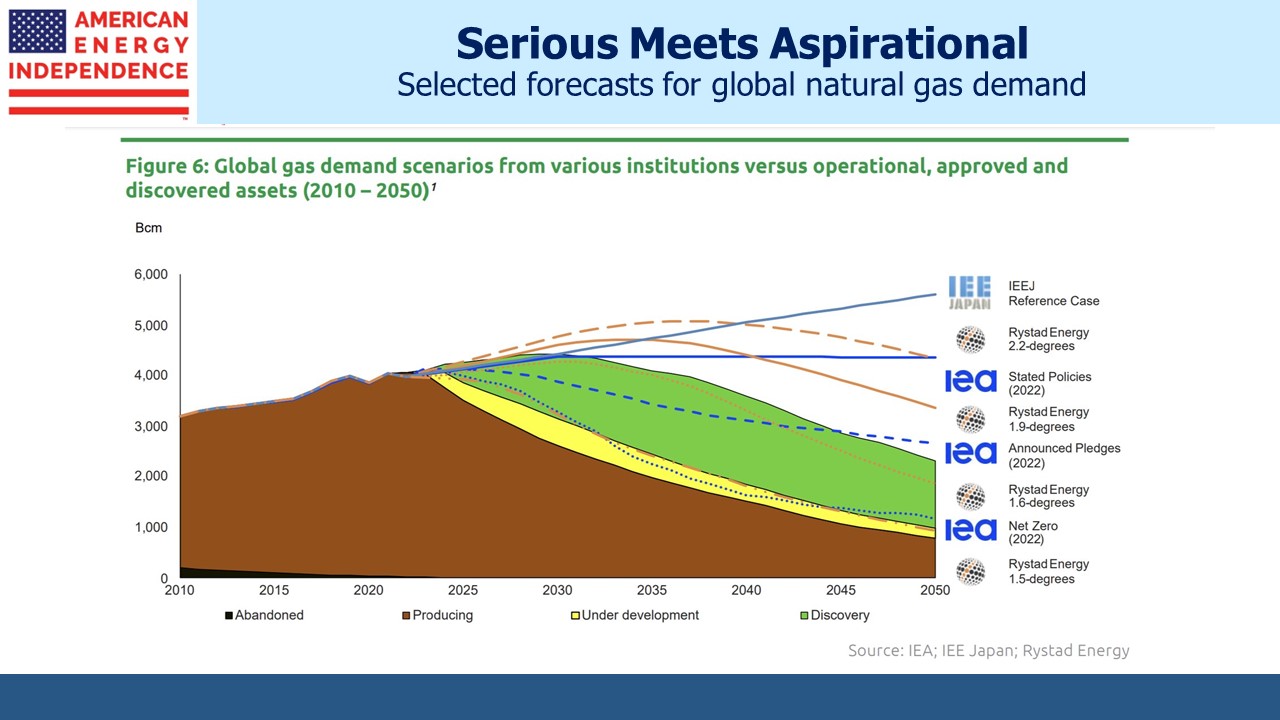

The UN projects oil production will reach around 114 Million Barrels Per Day (MMB/D) by 2030 and 116 MMB/D by 2050 versus 102 MMB/D today. This is based on analyzing the twenty largest producing countries. The International Energy Agency sees demand peaking within a few years. Their forecasts look increasingly political and less grounded in reality.

There are many policies and technologies available today that can be harnessed to reduce emissions. These include phasing out coal in favor of natural gas, dramatically increasing nuclear power, carbon capture and deploying hydrogen as described above. Anybody who describes themselves as worried about climate change but doesn’t support these isn’t interested in solving the problem. Claiming the world should fully rely on solar and wind because they’re cheaper betrays an absence of thought about how we use energy.

We feel pretty good that natural gas infrastructure will continue to support a substantial part of America’s energy needs.

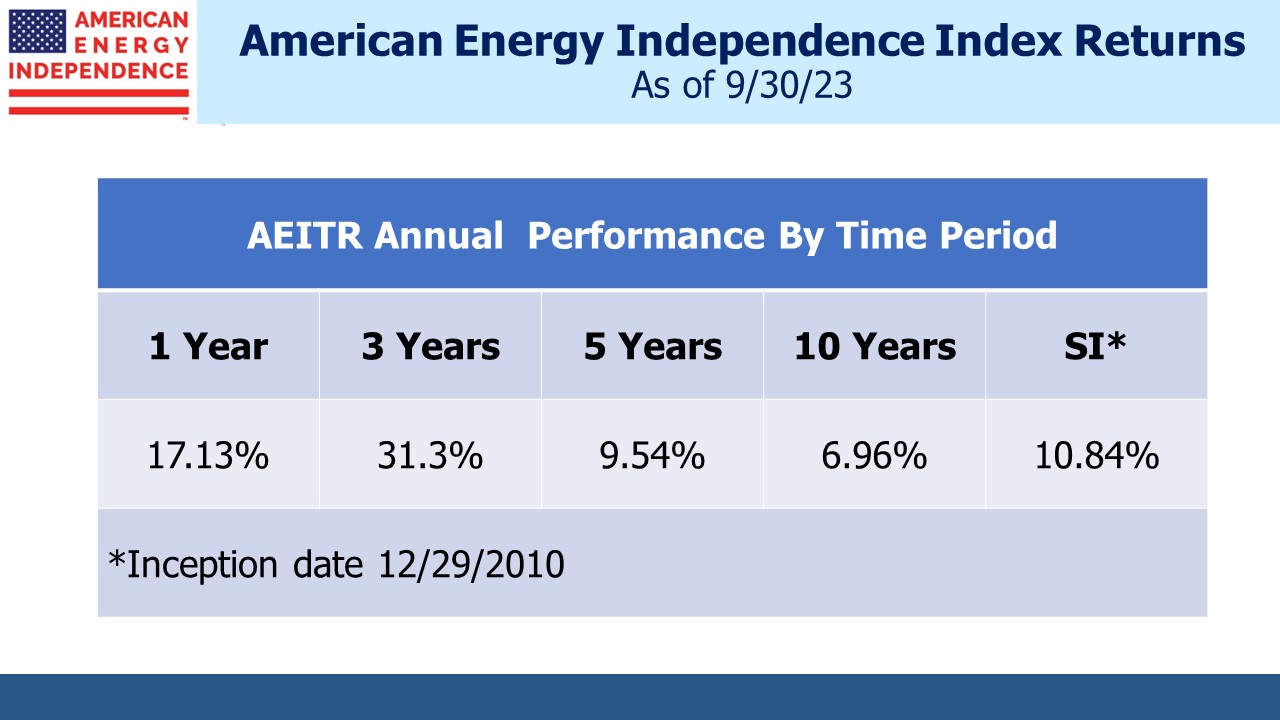

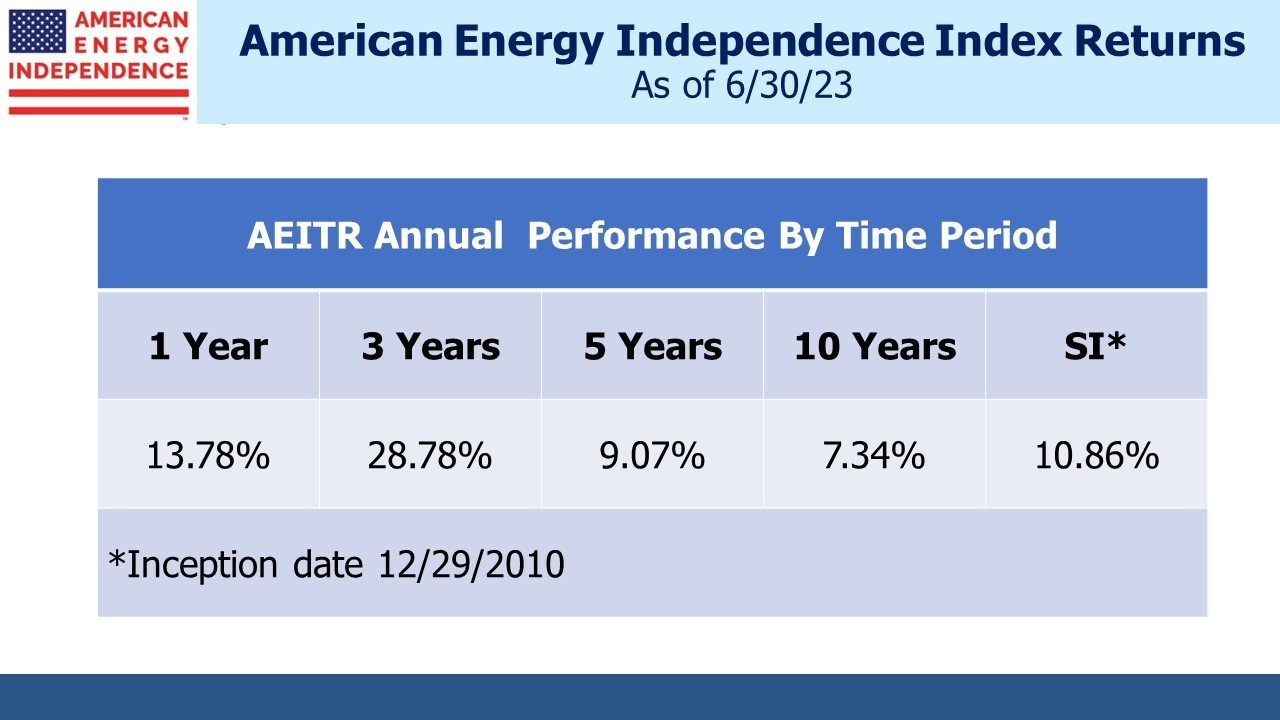

We have three have funds that seek to profit from this environment: