EnLink Aims for Positive Free Cash Flow

It’s a sign of the market’s evolving view of pipeline stocks that EnLink Midstream’s (ENLC) distribution cut was followed by a modest bounce in the stock. A cut had been widely expected, and during the conference call with analysts some questioned whether the 34% reduction was big enough. MLP investors are no longer solely focused on distribution yield as a measure of value.

ENLC is technically an LLC rather than a partnership. It has elected to be taxed as a corporation so as to broaden its investor base by issuing 1099s rather than K-1s. But its owner base remains dominated by MLP funds, perhaps because the weaker governance of an LLC dissuades many institutions who might otherwise consider the stock.

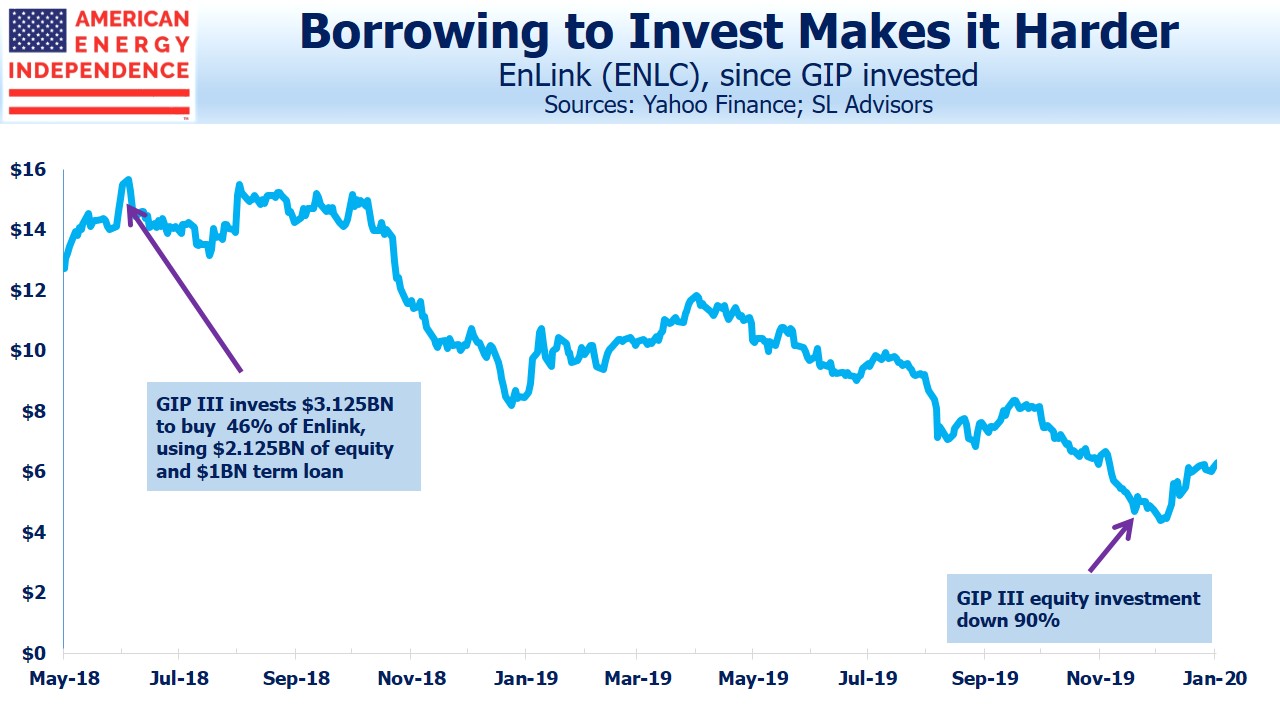

One unanswered question remains the influence of Global Infrastructure Partners (GIP) in setting strategy. GIP has taken a beating since investing $3.125BN in July 2018 (see Leverage Wipes Out Investor’s Bet on Enlink). GIP took on $1BN in debt and the subsequent collapse in ENLC’s stock has virtually wiped out the equity. The deteriorating fundamentals of Enlink’s business since GIP’s investment highlight that private equity often brings little to the table besides cash (and additional leverage). Uncertainty about GIP’s intentions remains a negative, and ENLC has offered little information. CEO Barry Davis simply said they exchange information with GIP on what each is seeing in the marketplace, which means either he doesn’t know much useful about GIP’s plans or what he does know isn’t positive. Preserving enough cashflow to GIP from the reduced dividend to service their debt was regarded by most as a factor.

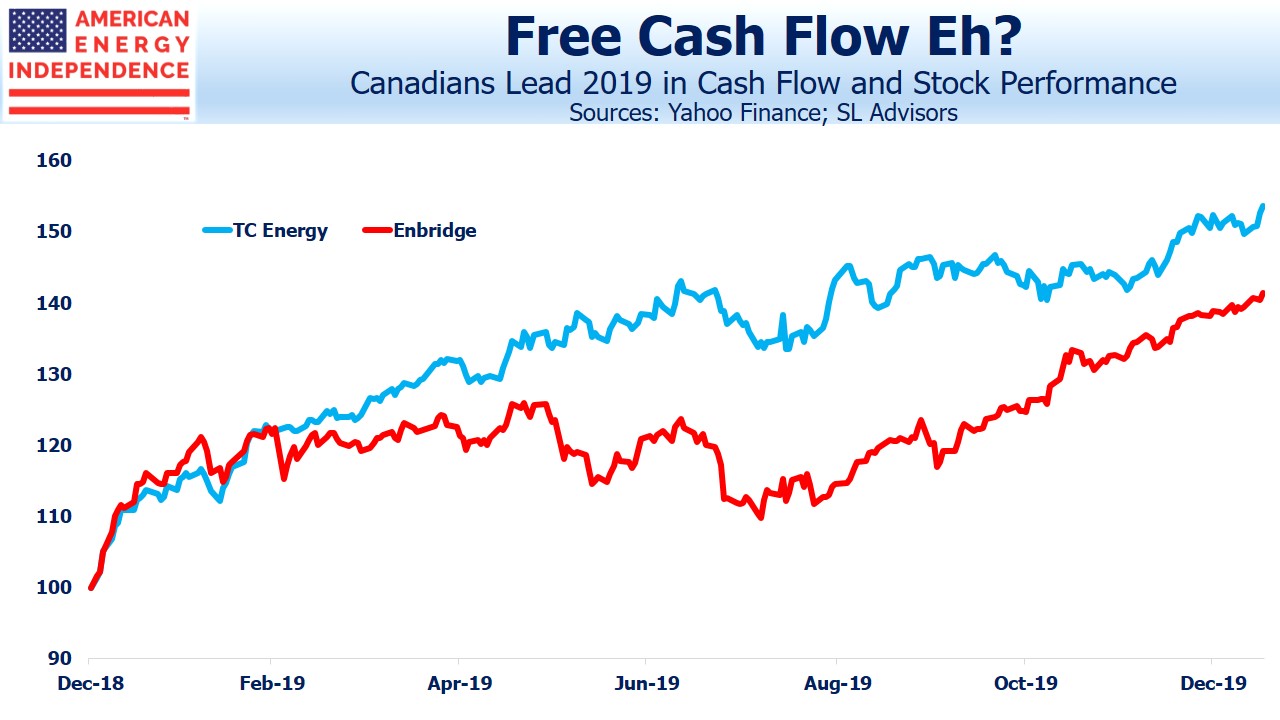

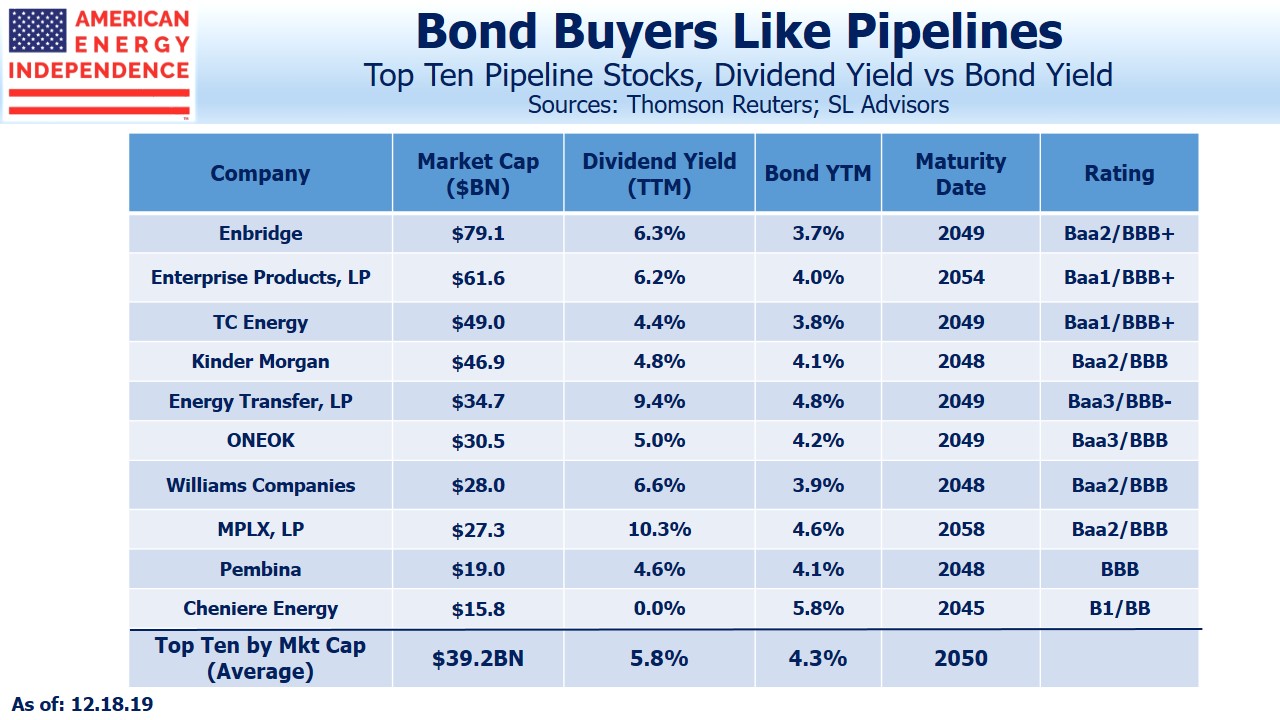

Investors were mildly cheered by the discussion of Free Cash Flow (FCF) and the fact that it’ll be positive in 2020. Midstream energy infrastructure stocks have been rewarded for generating FCF. We estimate that almost half the industry’s 2019 FCF came from two big Canadian companies, TC Energy (TRP) and Enbridge (ENB). Both were star performers last year, returning 58% and 39% respectively including dividends. In The Coming Pipeline Cash Gusher last year we highlighted the industry’s growing FCF. Following 4Q earnings in the next few weeks we’ll update those projections, but they’re likely to be largely on track.

Even after the cut, ENLC now yields 13%, roughly 2X the yield on the American Energy Independence Index. This new dividend is presumably secure, not least because it must align with GIP’s debt servicing needs. Questions remain about long term performance in its assets located in Oklahoma and North Texas. Devon Energy (DVN), once ENLC’s owner and significant customer, triggered the weaker performance by divesting from plays in those regions. ENLC is still struggling to convince investors that their long term future is secure, and as with many pipeline companies the Permian in west Texas looks more attractive.

More clarity around GIP would be helpful. ENLC isn’t the traditional toll model with secure volume-backed contracts extending out many years. Customer drilling activity remains a critical factor in driving their performance. But for now they seem to be operating from the front foot. The dividend is also fully classified as a non-taxed return of capital, an appealing feature for those taxable investors who care about such things. It’s likely to remain that way for at least another three years due to a depreciation shield offsetting taxable income. RW Baird estimates 2021 FCF of $115MM, which on its current market cap of $2.85BN is a 4% FCF yield. However, that’s after the 13% distribution, so represents a high total FCF yield to equity holders. FCF is a recent discovery for many energy companies, and the fact that ENLC can show some ought to provide some support for the stock.

We are invested in ENB, ENLC and TRP