ESG Has No Clothes

Offering investments tailored to ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) criteria is a growing source of fee income for Wall Street. Morningstar calculates that 65 US funds have been repackaged into ESG funds since the beginning of 2019. Investors are attracted by the notion of holding virtuous stocks, but companies and fund managers must also find the flexibility around what constitutes an ESG-eligible stock to be appealing too.

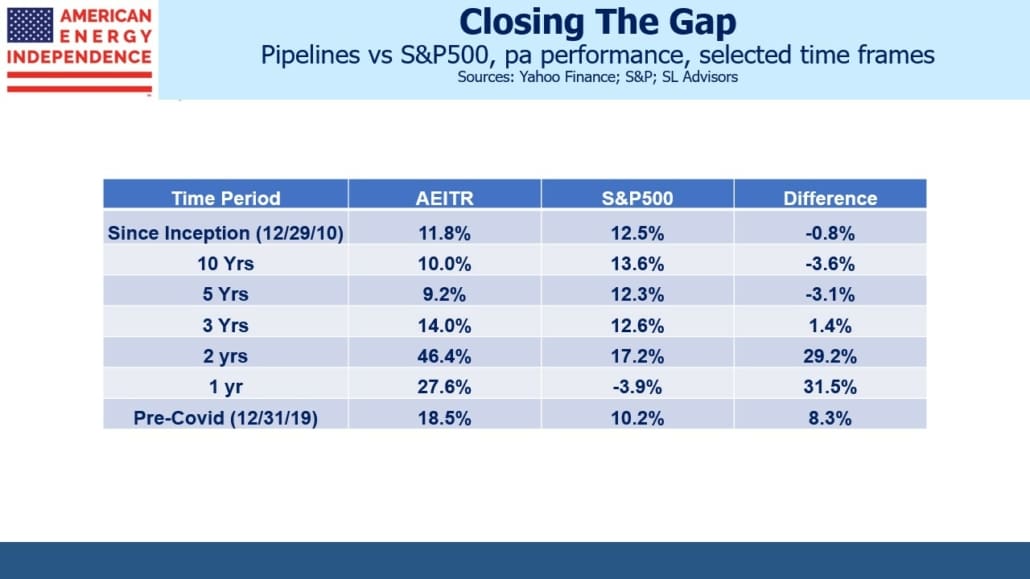

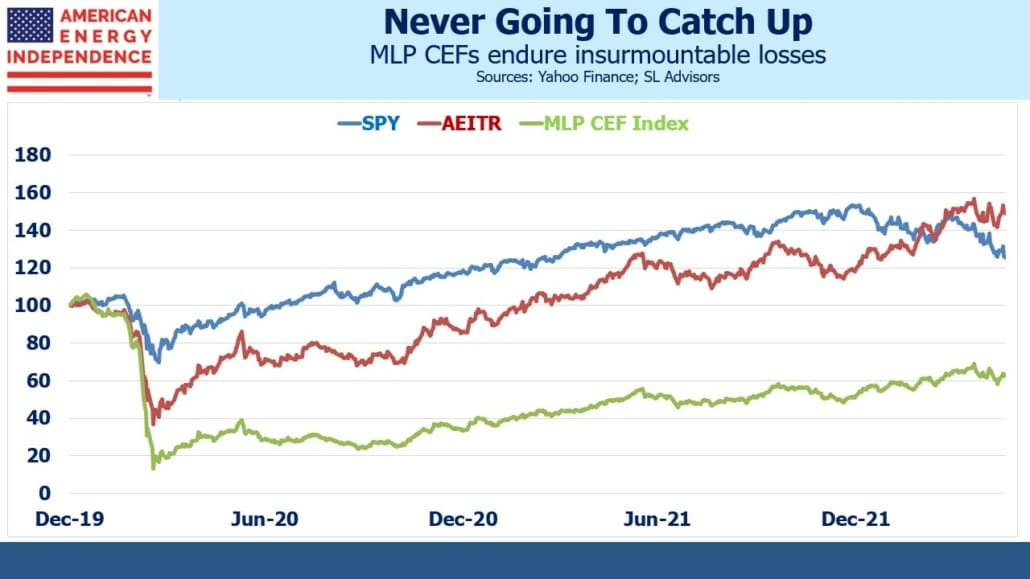

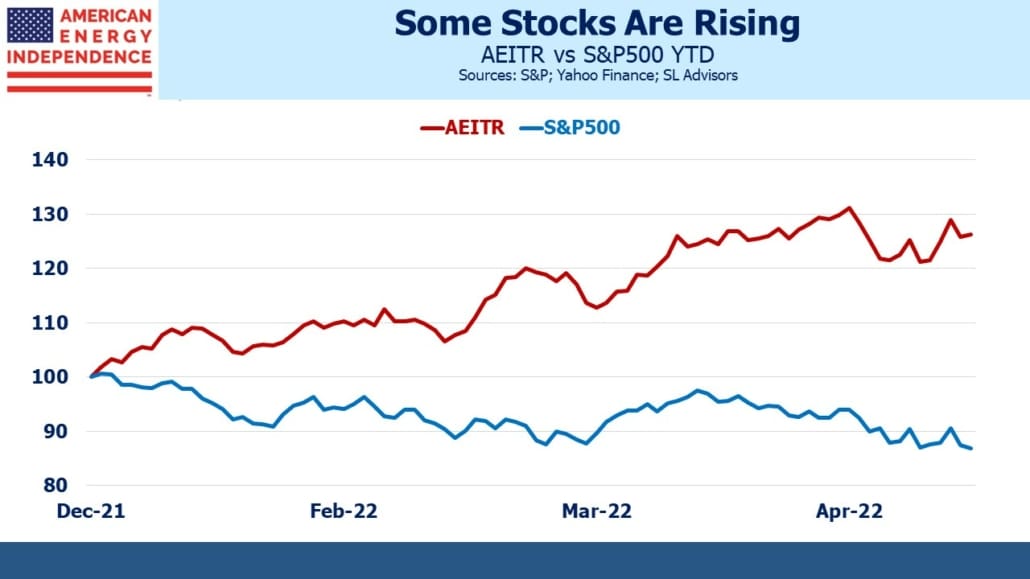

A year ago we looked at the then-largest ESG ETF, the iShares ESG Aware MSCI USA ETF (ESGU), which had $15BN in AUM (see Pipelines Are ESG). ESGU looks so much like the S&P500 that their returns are 0.99 correlated.

In the past year, ESGU has lagged the S&P500 by 2.5%. This underperformance has come just as the concept is coming under fire. Tesla (which is in ESGU) was dropped from S&P’s ESG index, prompting CEO Elon Musk to tweet that “ESG is a scam. It has been weaponized by phony social justice warriors.”

Musk is right that it’s a scam, although he hadn’t been a vocal critic until recently. Tesla was dropped even though its “ESG score” was stable, because its sector peers improved theirs. S&P explained that it’s not enough to be “taking fuel-powered cars off the road.”

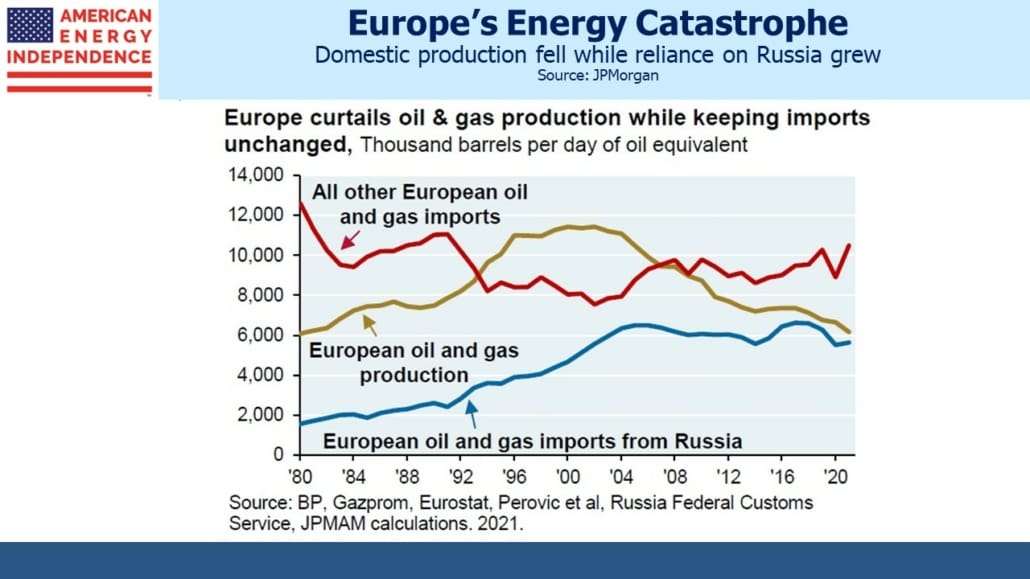

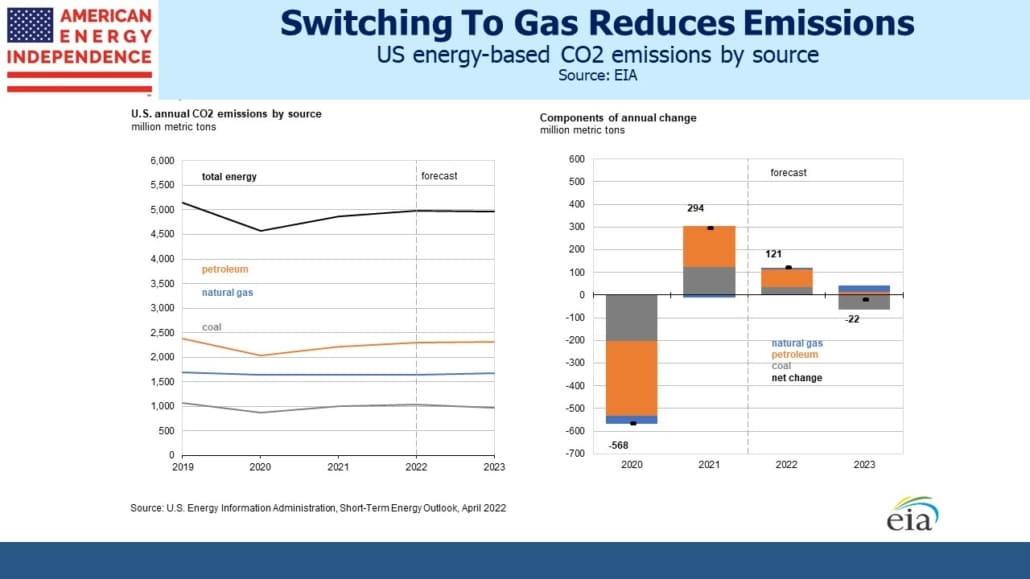

Tesla drivers are passionate owners, but many overlook that 61% of US electricity generation is from fossil fuels, including coal (22%). It varies by state, but buyers of electric vehicles in Kentucky, West Virginia and Wyoming where coal dominates electricity production (69%, 88% and 80% respectively) are generating more harmful emissions than if they bought a conventional car.

Tesla was the biggest company to be dropped, but others included Berkshire Hathaway and Johnson and Johnson. Wells Fargo was dropped for being non-compliant with the United Nations Global Compact, which says it’s “the world’s largest corporate sustainability initiative”.

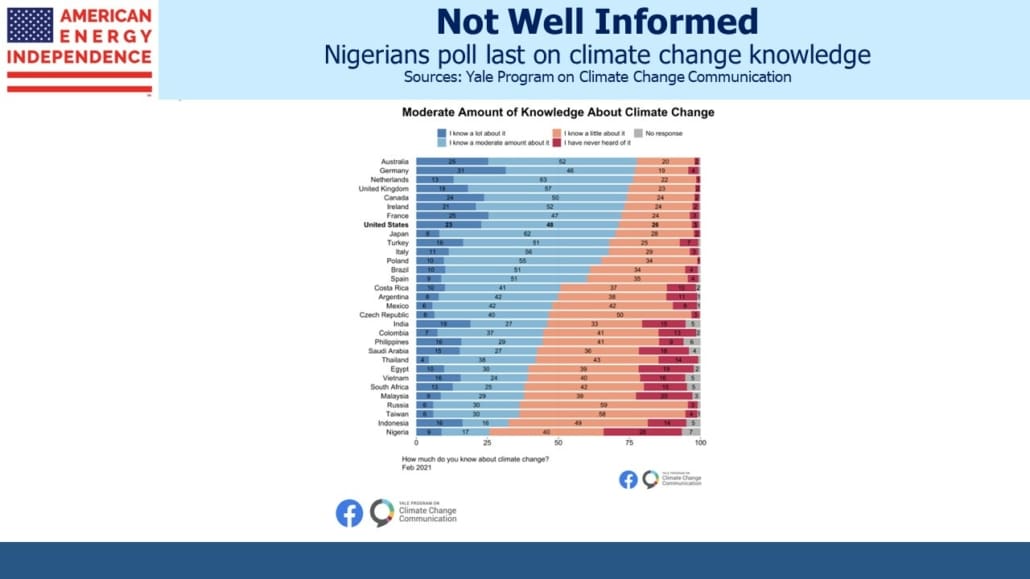

HSBC’s head of responsible investing, Stuart Kirk, may have given his swansong by accusing policymakers of overstating the financial risks of climate change. In a delightfully incongruous presentation at the FT’s Moral Money Europe Conference, he said, “there was always some nut job telling me about the end of the world.” His message was a rejection of the orthodoxy which often lapses into hyperbolic predictions that life as we know it is in its final decade.

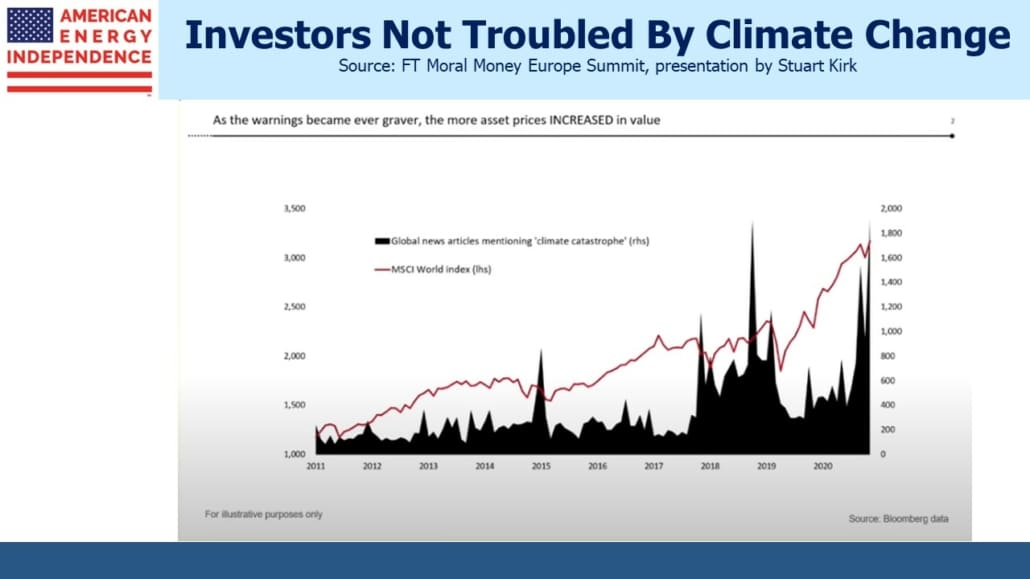

Kirk notes that the projections of economic loss are inconsequential. The UN’s IPCC report estimates as much as a 5% loss of global GDP by 2100 due to climate change. This is a trivial impact given that even 2.5% annual growth by then will leave the economy 6.86X bigger than it is today. If it’s only 6.52X bigger instead, few will care. It’s the difference between annual growth of 2.5% and 2.433%. Global stock markets aren’t visibly affected by the jump in news articles mentioning “climate catastrophe”.

Kirk is obviously ready for a career change. He complained about the inordinate time he spends with regulators discussing HSBC’s climate exposure, when he sees much more immediate threats such as cybercrime, inflation and pandemics. He has been suspended pending an internal review. Stuart Kirk will likely become a hero to those who believe that adaptation to a warmer planet deserves more attention than it receives.

ESG is being exposed as the emperor with no clothes. The SEC is about to crack down on misleading ESG investment claims by fund managers. SEC chair Gary Gensler said “It is easy to tell if milk is fat free. It might be time to make it easier to tell whether a fund is really what they say they are.”

Gensler might care to examine the Dow Jones Sustainability North America Index, whose owners display a sense of humor by continuing to include defense contractors Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman as constituents.

The main problem with ESG is its infinite malleability. ESGU, which now has $23BN in AUM, includes almost the entire S&P500. If everything is ESG, then nothing is. There is no clear differentiating feature. It’s been taken over by index providers and fund managers who have identified the profit potential in creating virtue-signaling investment products. ESG’s most important quality has been in attracting fund flows, which used to cause modest outperformance until the last year or so.

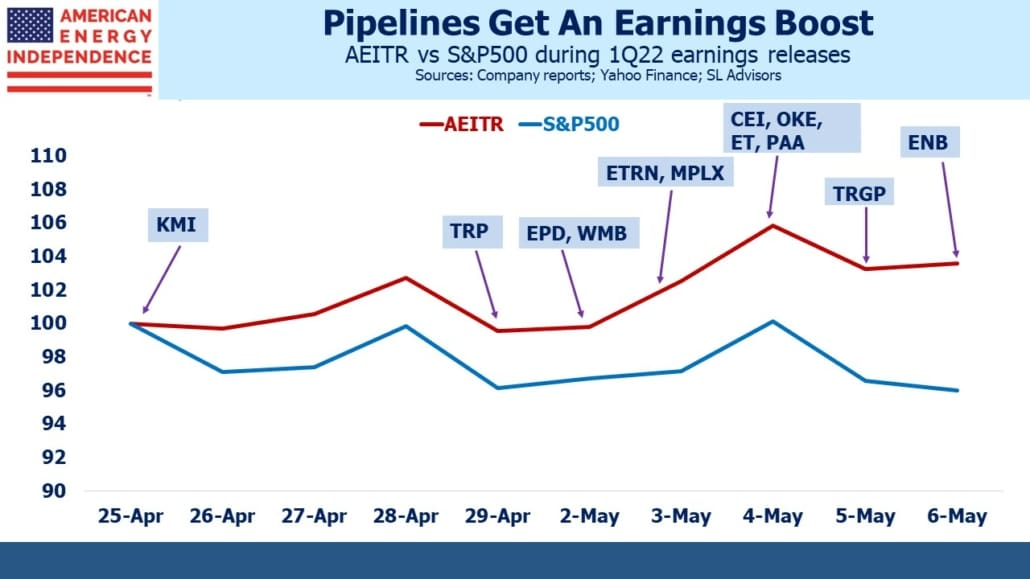

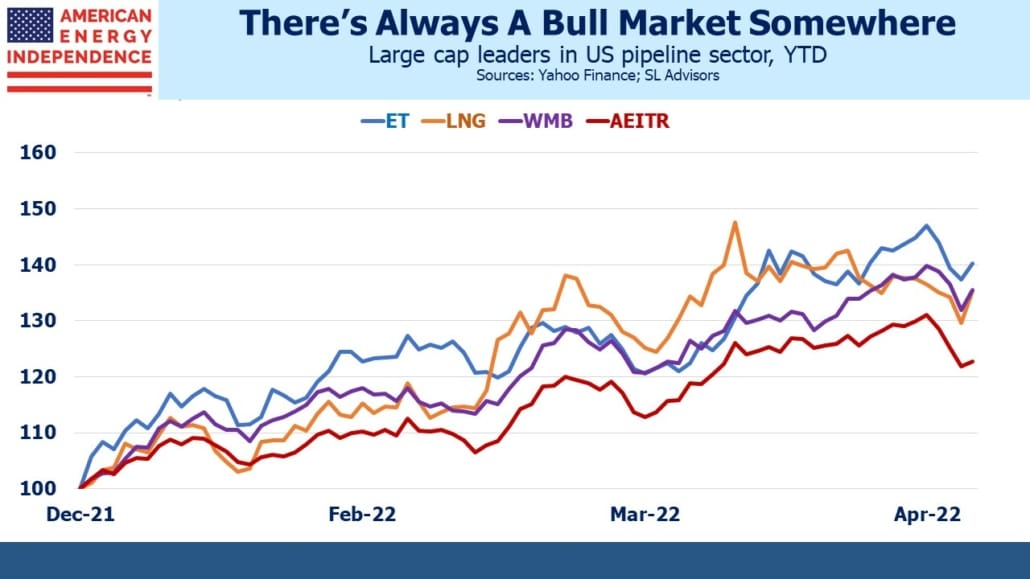

Unlike Dow Jones, ESGU doesn’t regard defense contractors as promoting sustainability, one reason why it’s been lagging the S&P500. However, it does include midstream energy infrastructure companies such as Kinder Morgan and Oneok. Cheniere is an addition since our last review of ESGU a year ago, but they have inexplicably dropped Williams Companies.

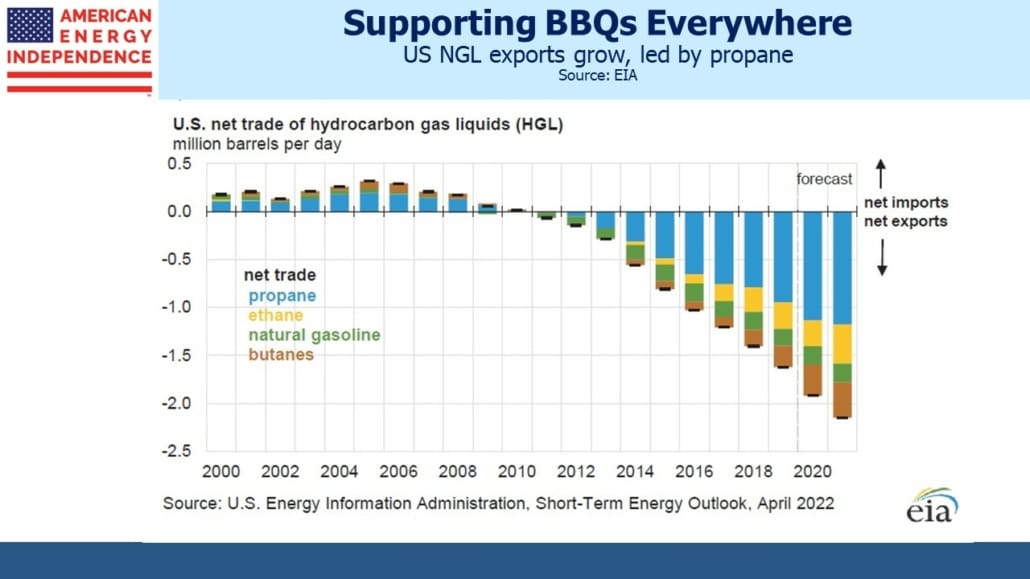

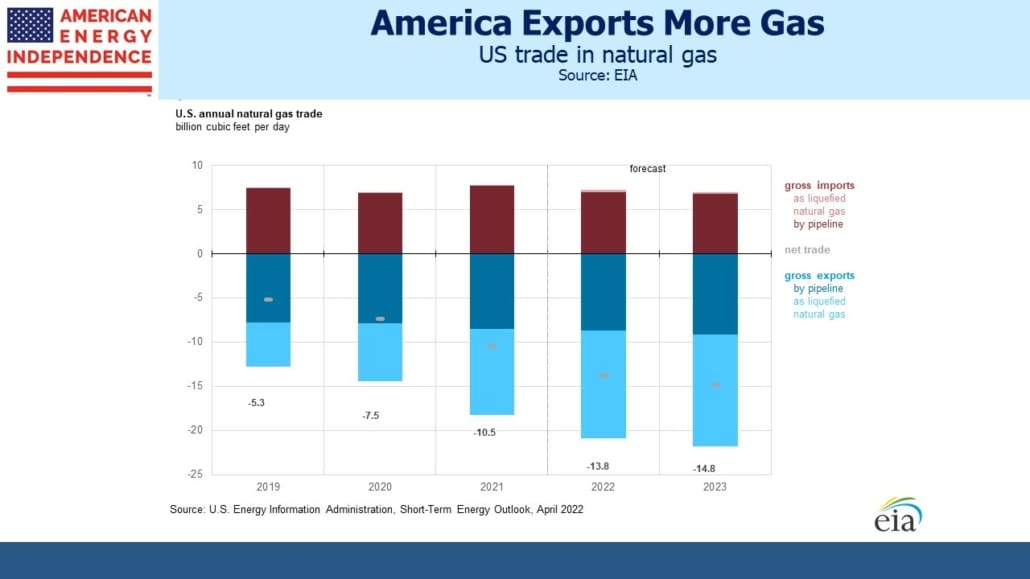

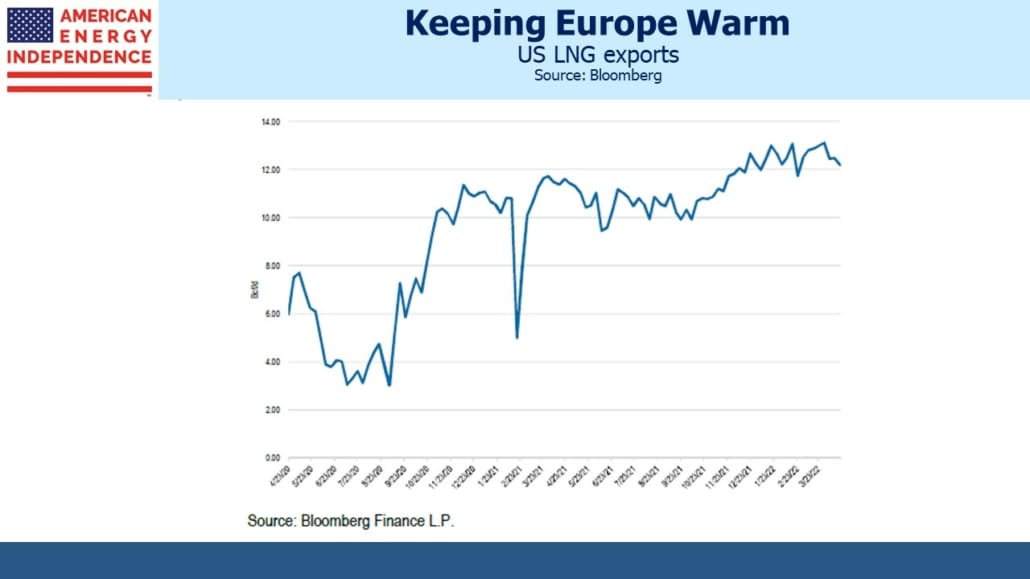

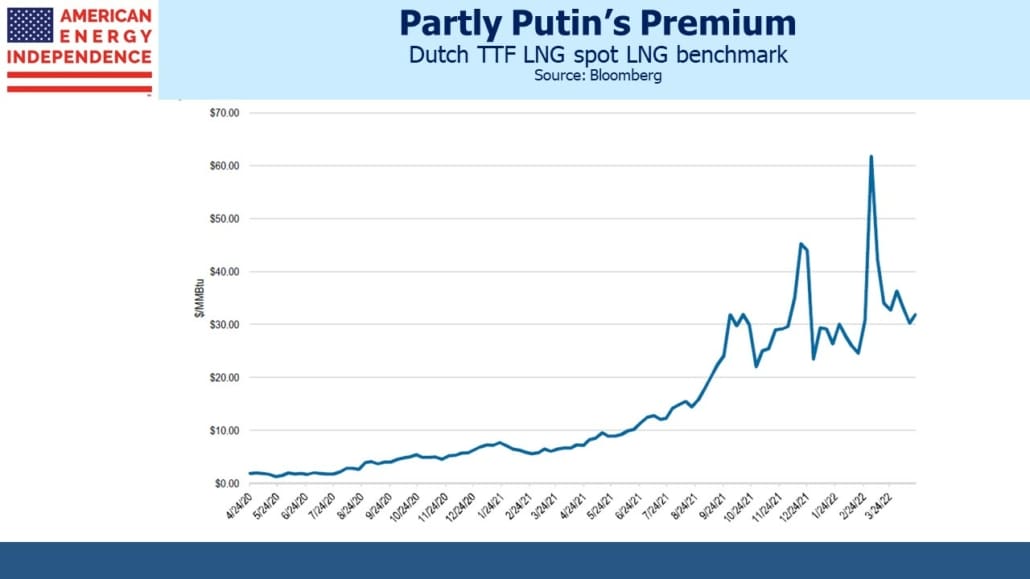

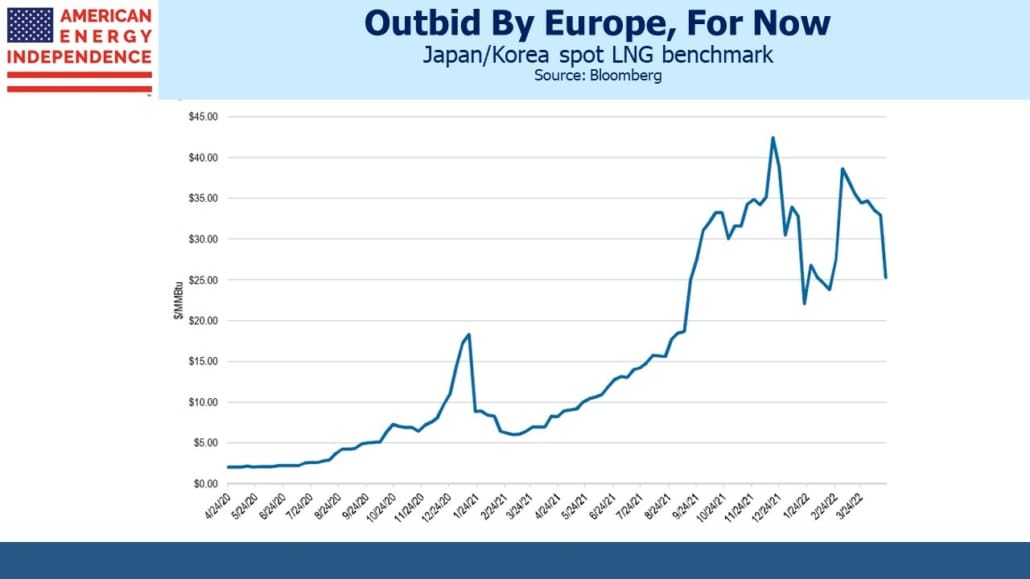

The Energy Information Administration tells us that biggest driver of America’s falling CO2 emissions has been switching power generation from coal to natural gas. Pipeline companies and Cheniere are doing more to keep the planet sustainable than any other company we can think of.

Elon Musk and Stuart Kirk are only the latest to challenge groupthink that has determined orthodoxy on climate change and the definition of doing good. There should be more to come.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Please see important Legal Disclosures.