4% Inflation Is Our Least Bad Option

Last week the WSJ warned that We May Be Getting Used To High Inflation. Only 9% of respondents in a recent survey think inflation is our most important problem. Government leadership (presumably the absence thereof) and “the economy in general” were both bigger concerns.

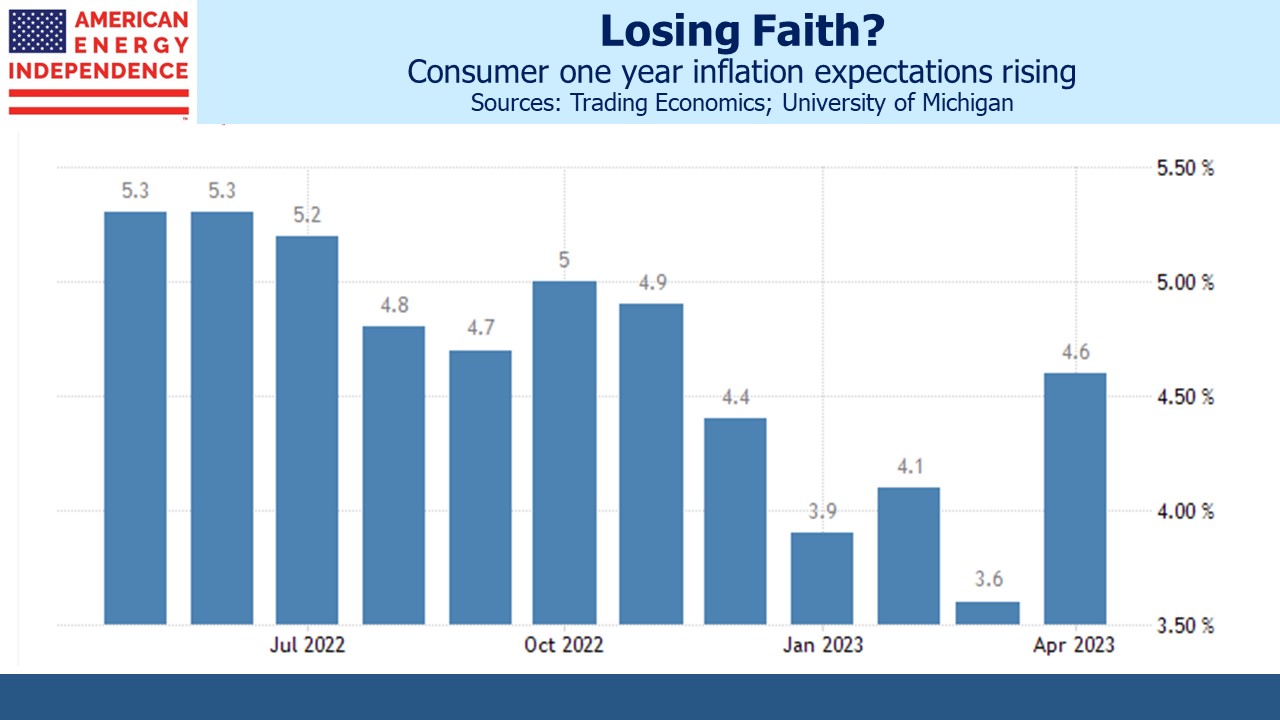

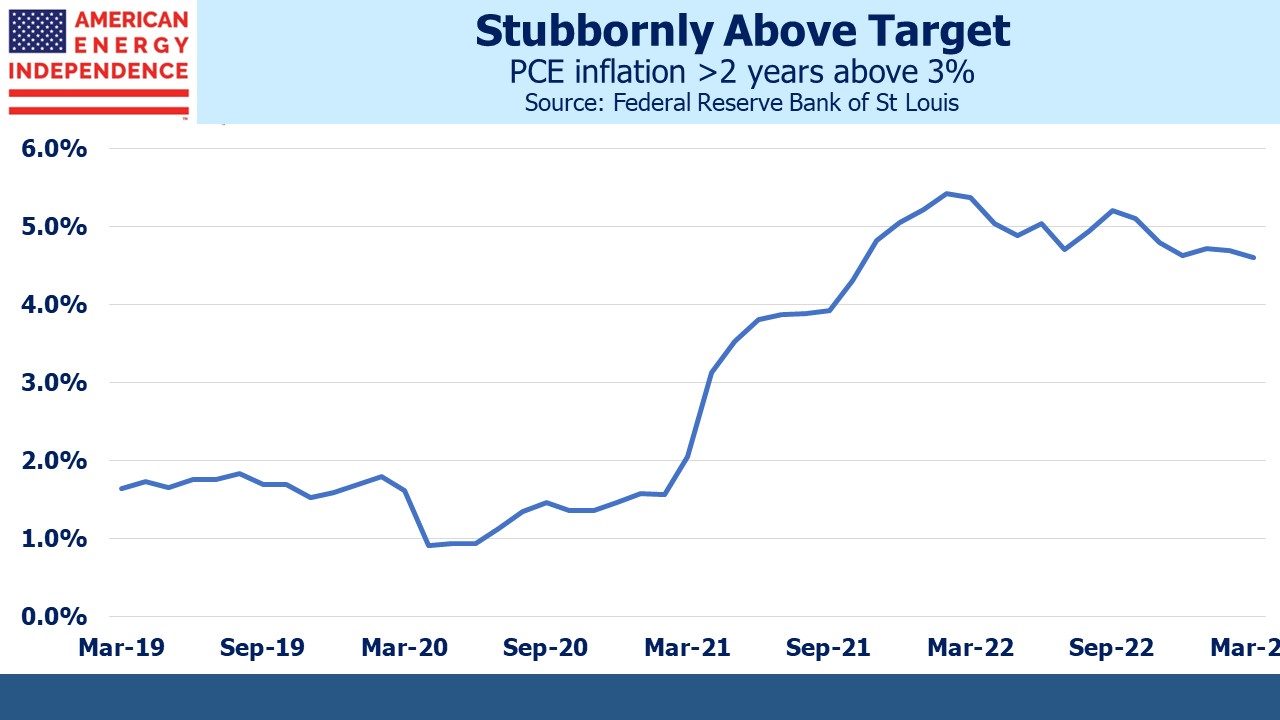

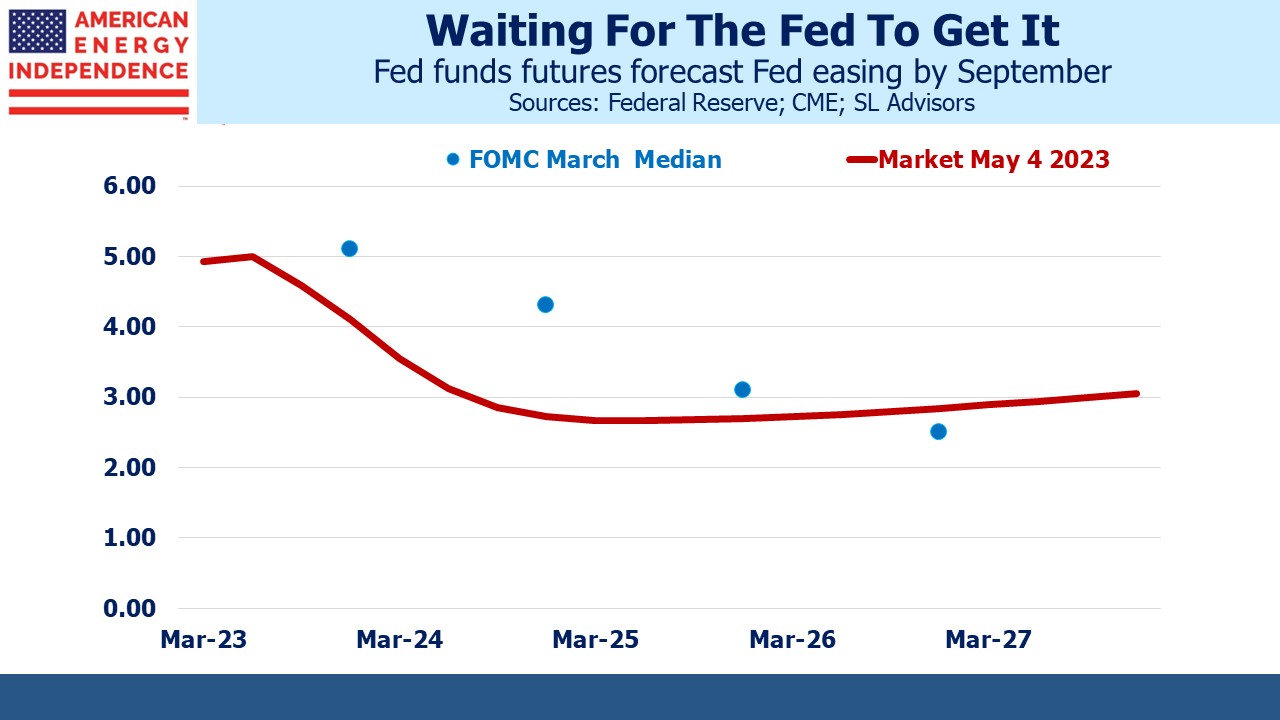

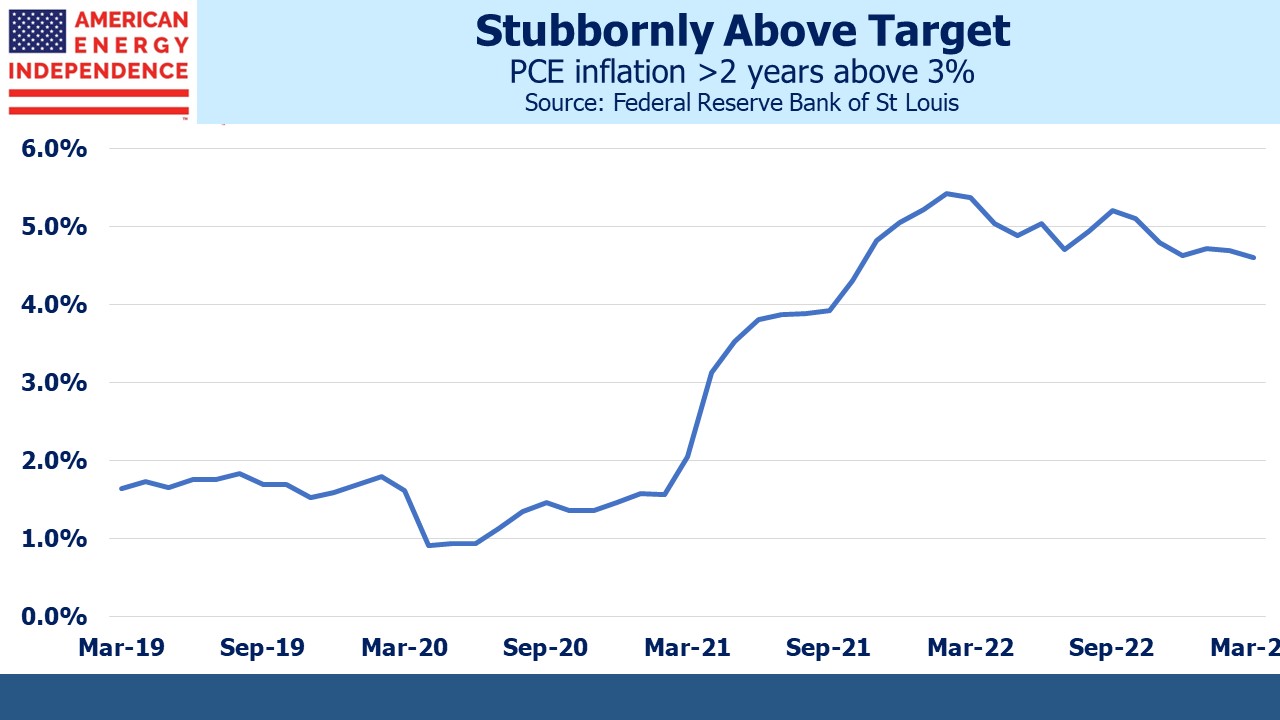

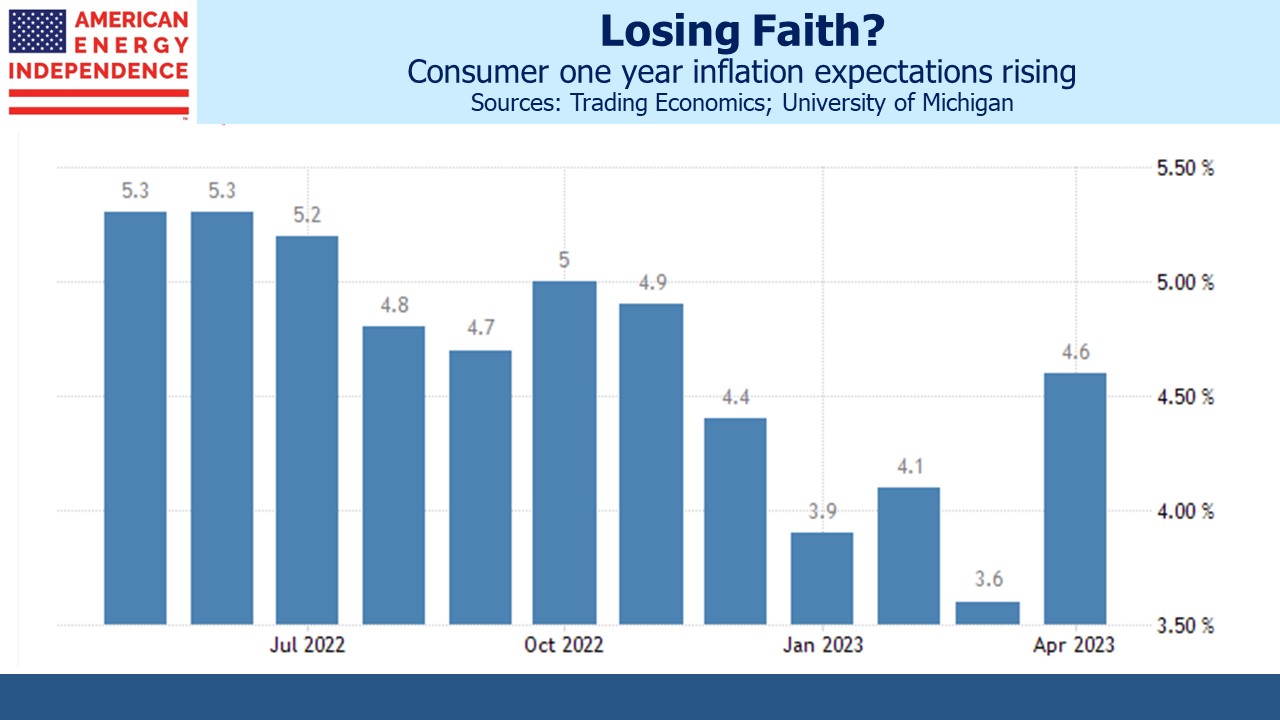

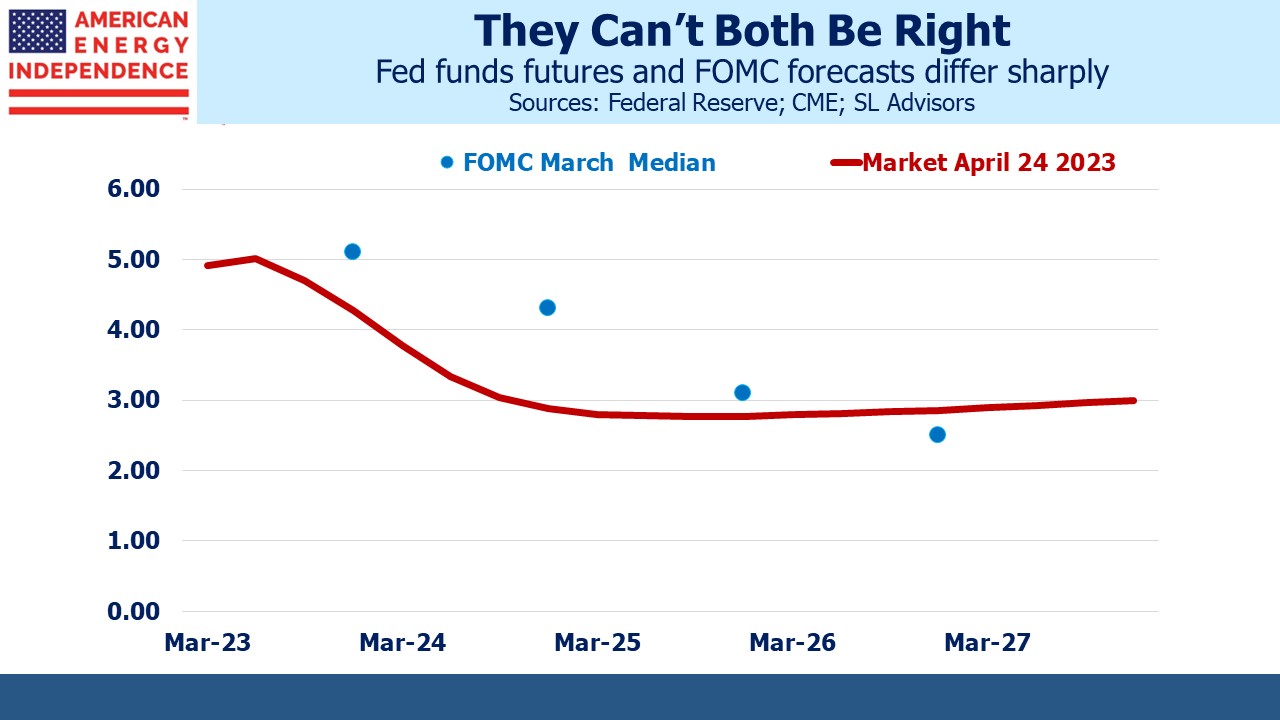

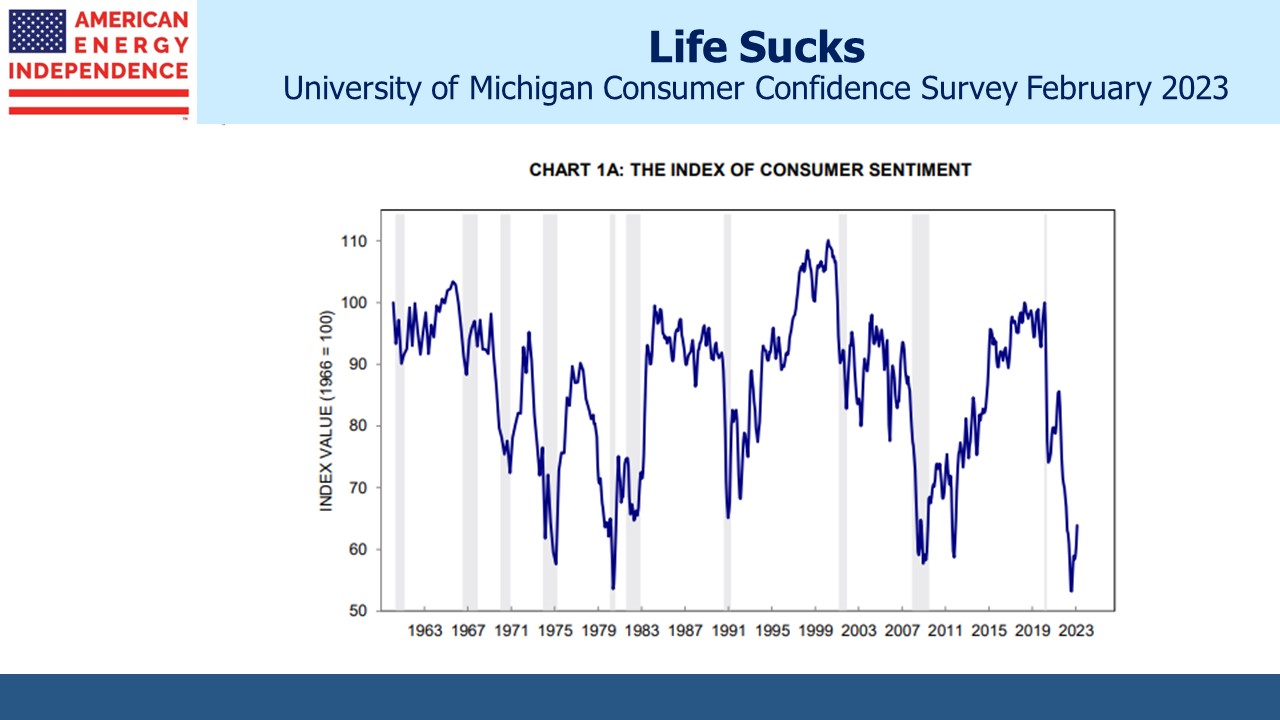

Americans are learning to live with higher inflation. The University of Michigan shows that one year inflation expectations among consumers have been rising all year. The Employment Cost Index is increasing at 5%, a figure generally felt to be inconsistent with 2% inflation. The Fed’s preferred Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) deflator has been above 3% for two years. These are all signs that households and businesses are adapting to a world of 3-4% inflation, not 2%.

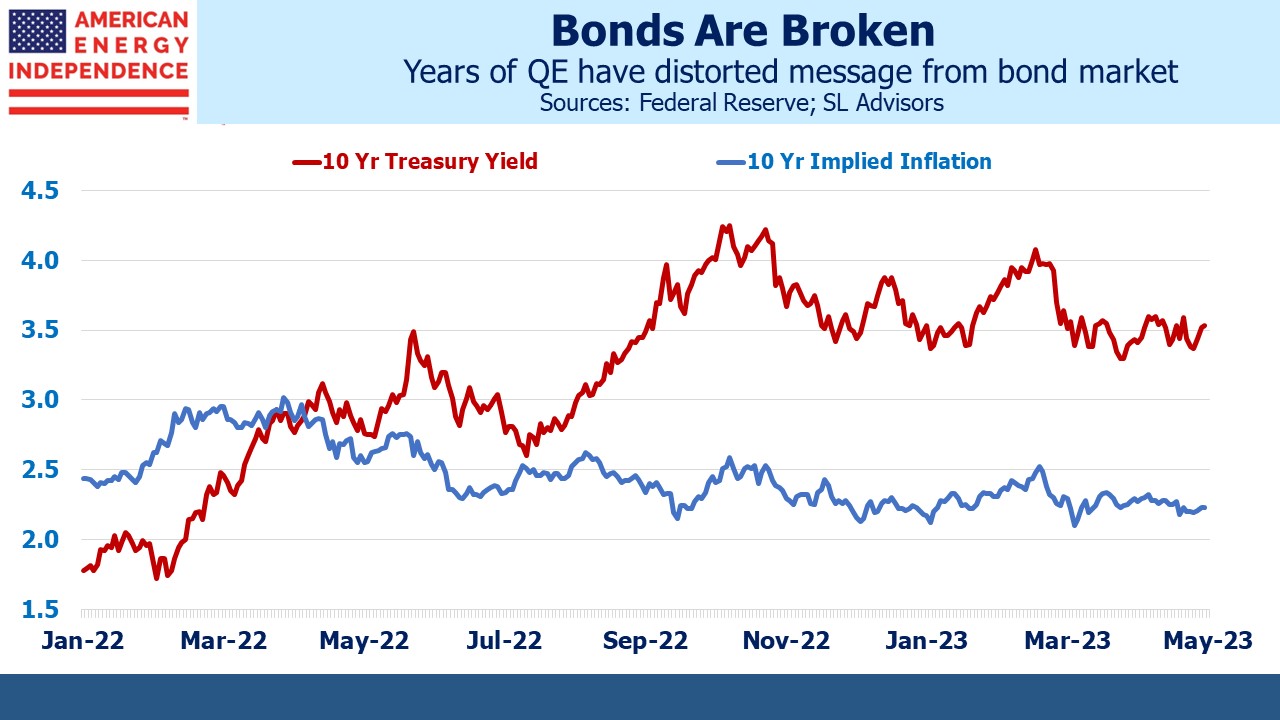

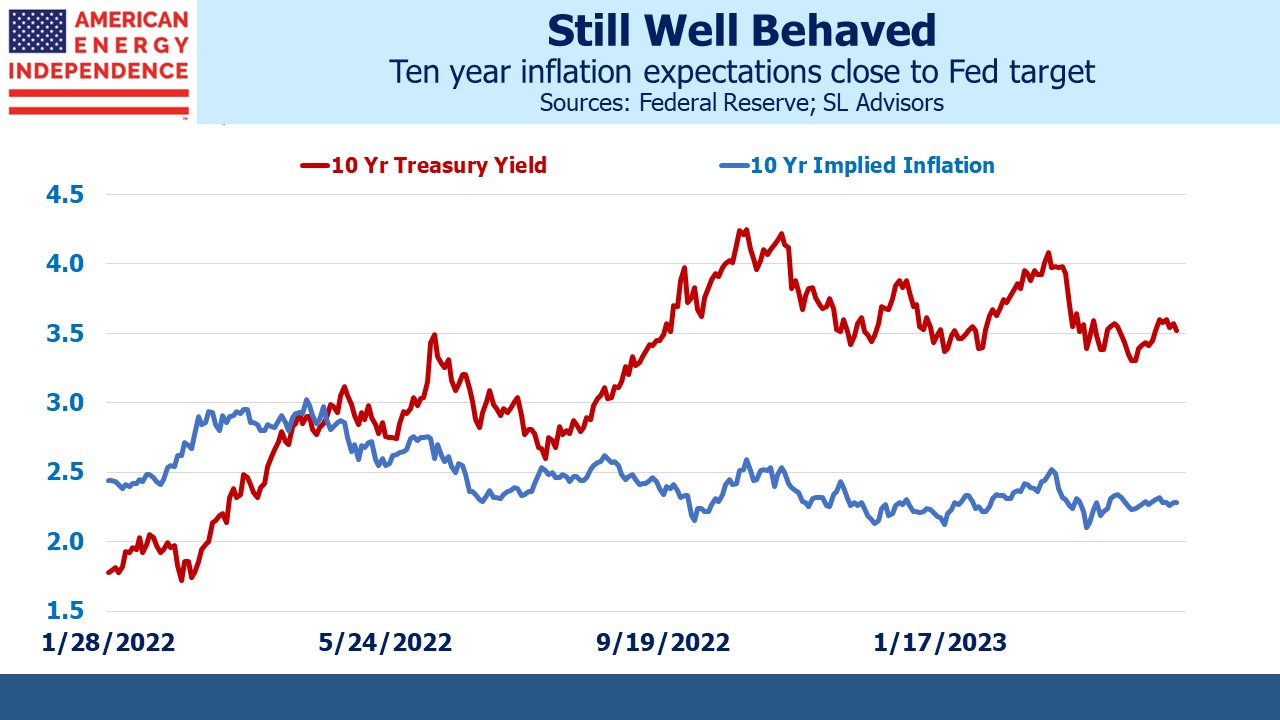

The bond market tells a different story. The spread between ten year treasury notes and TIPs implies investors expect CPI to average around 2.3% over the next decade. By this measure, markets have never been that worried about persistent inflation. It’s remained below 2.5% for most of the past year.

TIPs ought to be a reliable indicator, because return-seeking bond buyers are presumably putting considerable thought into their purchases. But to this observer it looks likely that years of Quantitative Easing (QE) along with $TNs held by foreign central banks (China; Japan) and others who want returnless liquidity have distorted the message bonds would otherwise communicate. Bonds are a broken indicator.

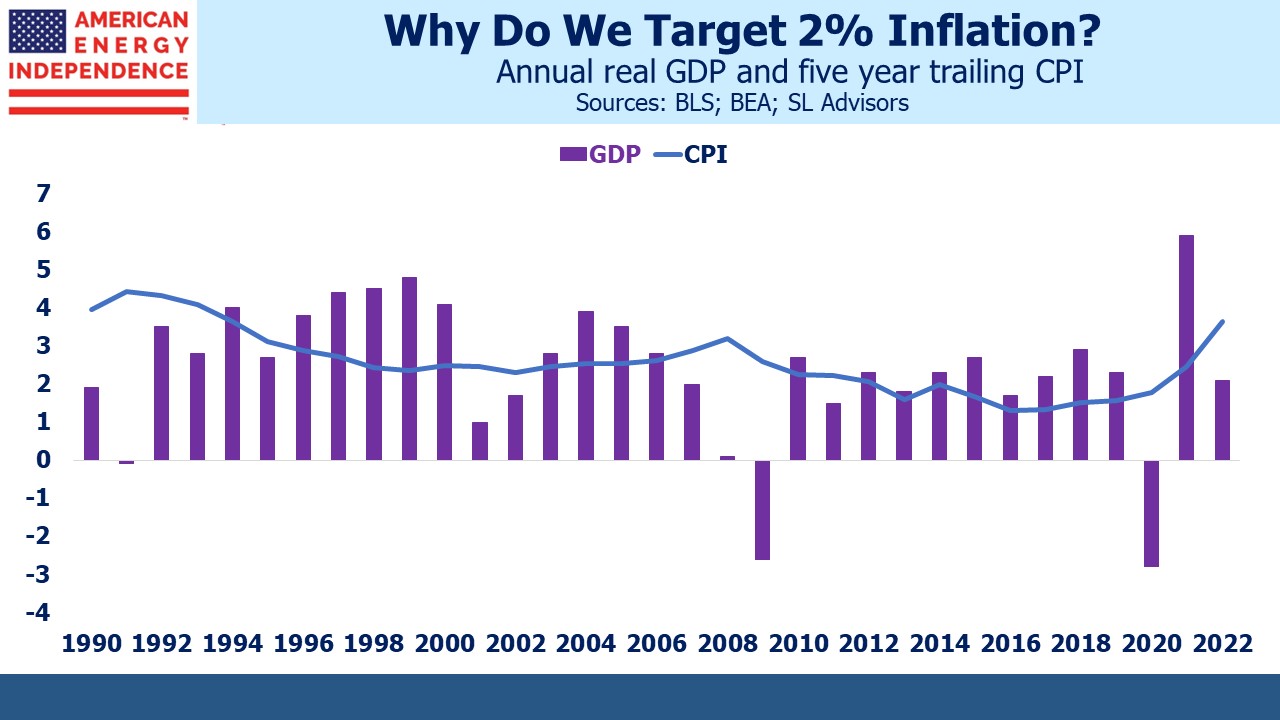

WSJ writer Greg Ip thinks Americans getting used to higher inflation “very bad news”. He’s right if the Federal Reserve regards embedded inflation expectations as in need of further monetary attention. But it’s not clear that 3% or 4% inflation is worse for real GDP growth than 2%.

Since 1990, five year trailing CPI inflation has ranged from 2-4% and had been slowly declining until the pandemic-induced jump. There is no statistical relationship with real GDP growth. That doesn’t mean that inflation doesn’t matter, but the data shows that if it’s relatively stable 2% isn’t any better than 4%. Central bankers have made 2% a religious tenet. It’s really a shibboleth.

Raising the debt ceiling will soon become the biggest concern of market participants, since negotiations look likely to reach or even pass the deadline. A rare flaw in the US constitution separates spending decisions from financing ones – Congress ought to raise the debt ceiling whenever they approve a budget. The debt ceiling standoff is what passes for serious consideration of America’s fiscal outlook in Washington, so every couple of years we wonder whether this game of chicken will go wrong. US credit default swap spreads are wider than Greece.

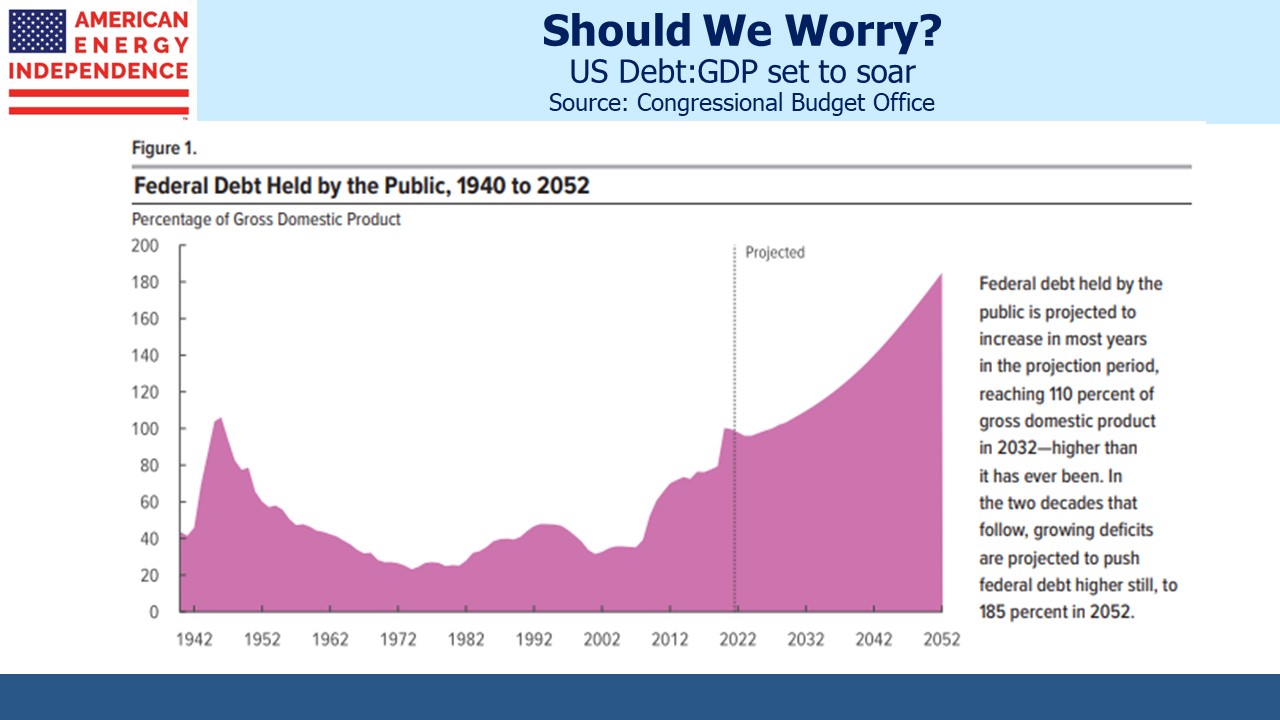

Our projected indebtedness is familiar with no solution in sight. The deficit barely registers as an issue. Politicians who suggest raising taxes or cutting spending soon get dumped by voters and move on to the more lucrative business of lobbying.

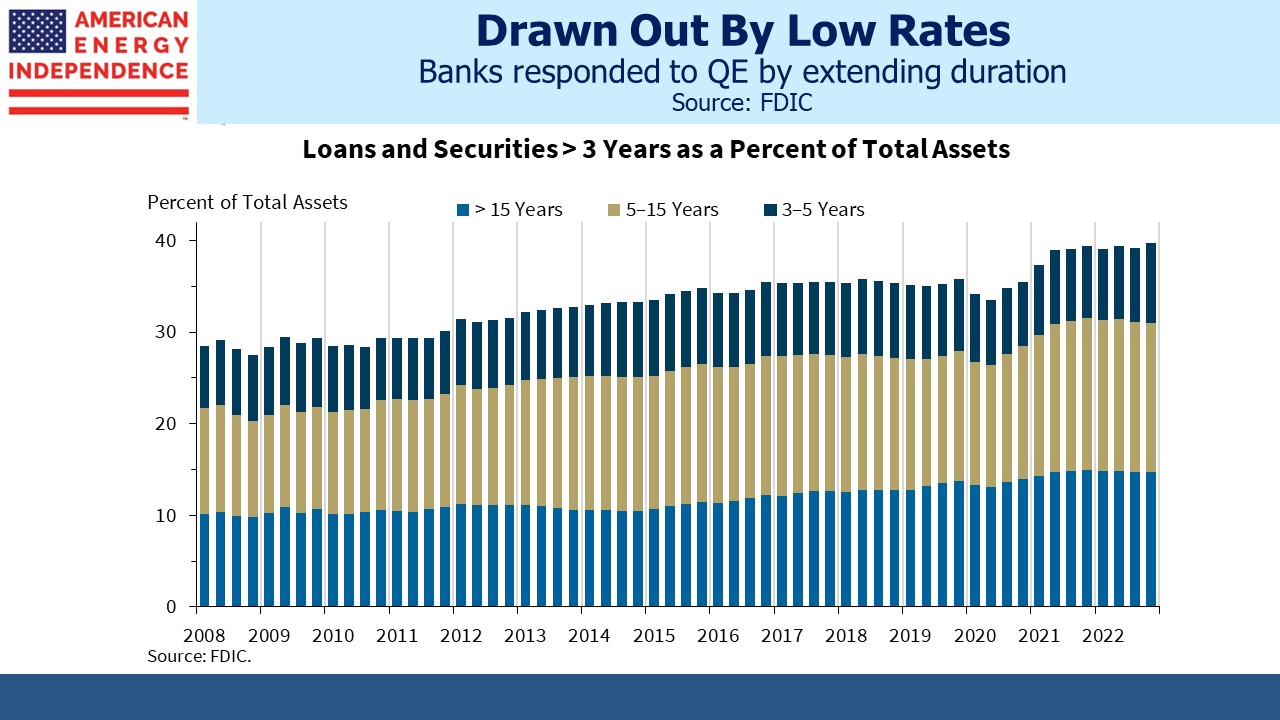

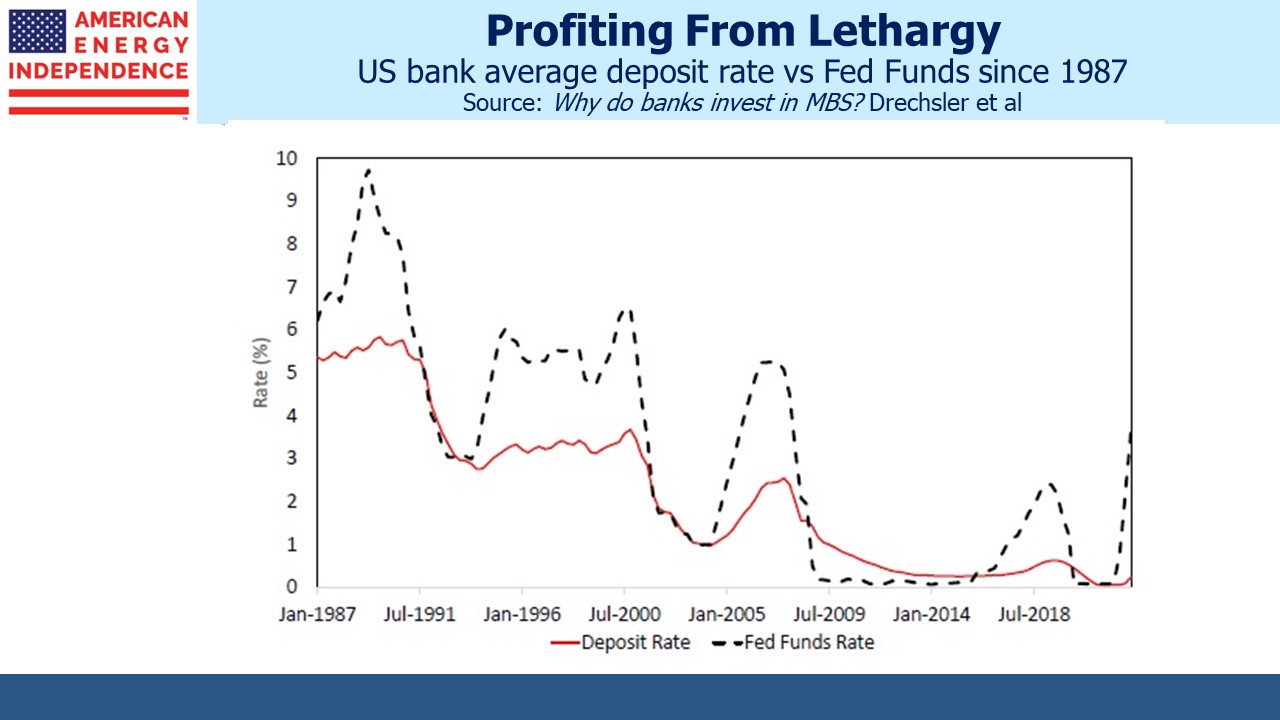

The Fed deserves their share of blame. Fifteen years of QE has held bond yields down, muting whatever warning of fiscal profligacy higher yields might otherwise transmit.

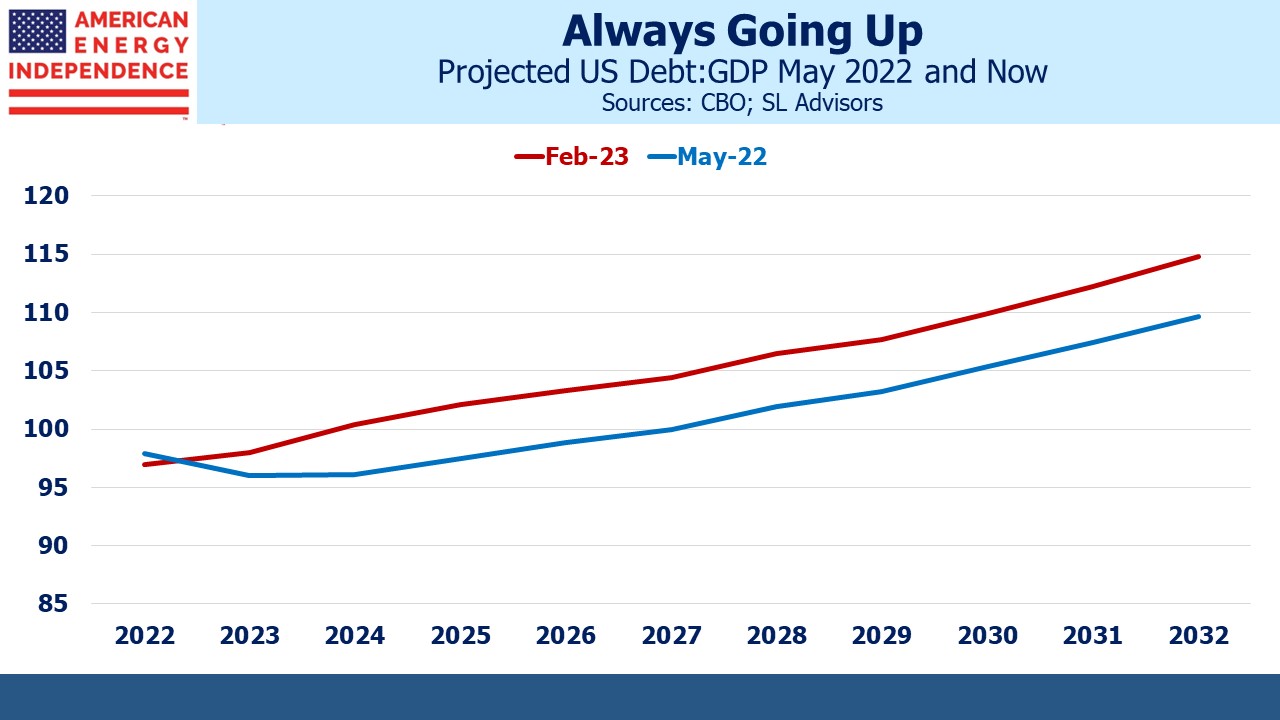

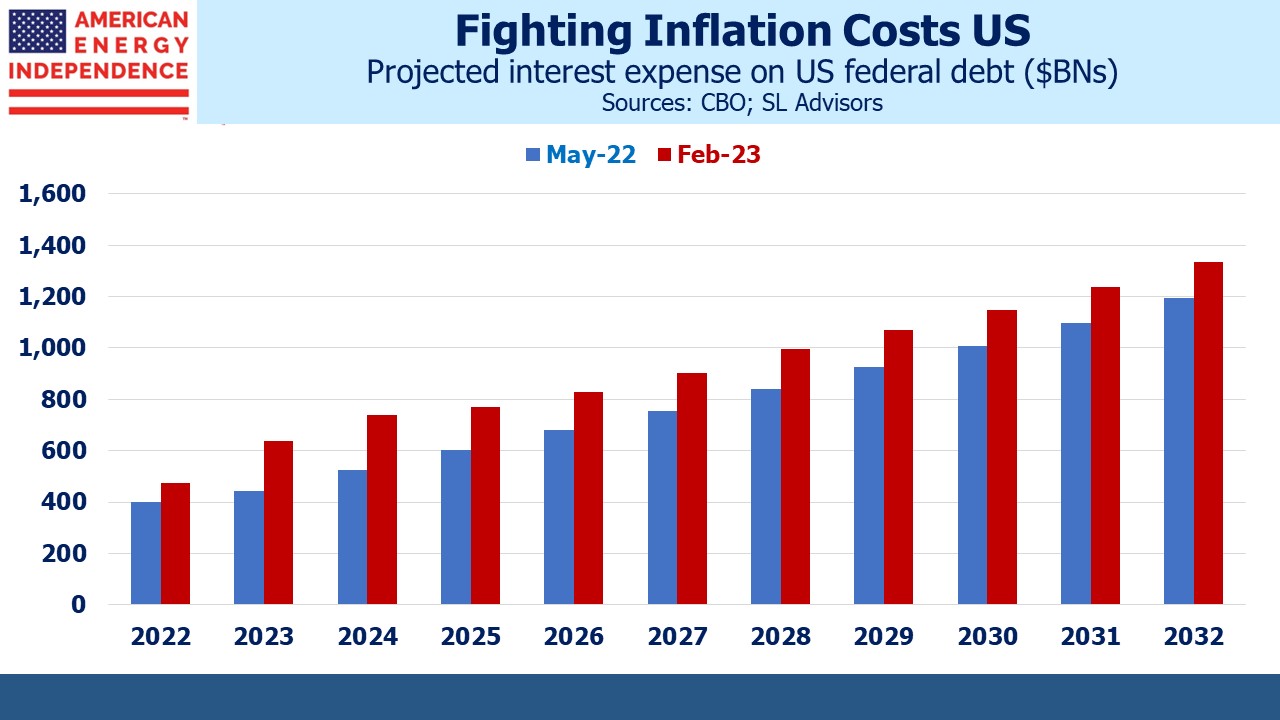

More recently, higher interest rates have brought various terrible milestones closer by two to three years (see How Tightening Impacts Our Fiscal Outlook). The February 2023 edition of The Budget and Economic Outlook, published by the Congressional Budget Office, was updated for the Fed’s tighter monetary policy compared with the previous publication in May 2022. Debt:GDP will now cross 100% in 2024 rather than 2027. Annual interest expense will reach $1TN in 2028 not 2030.

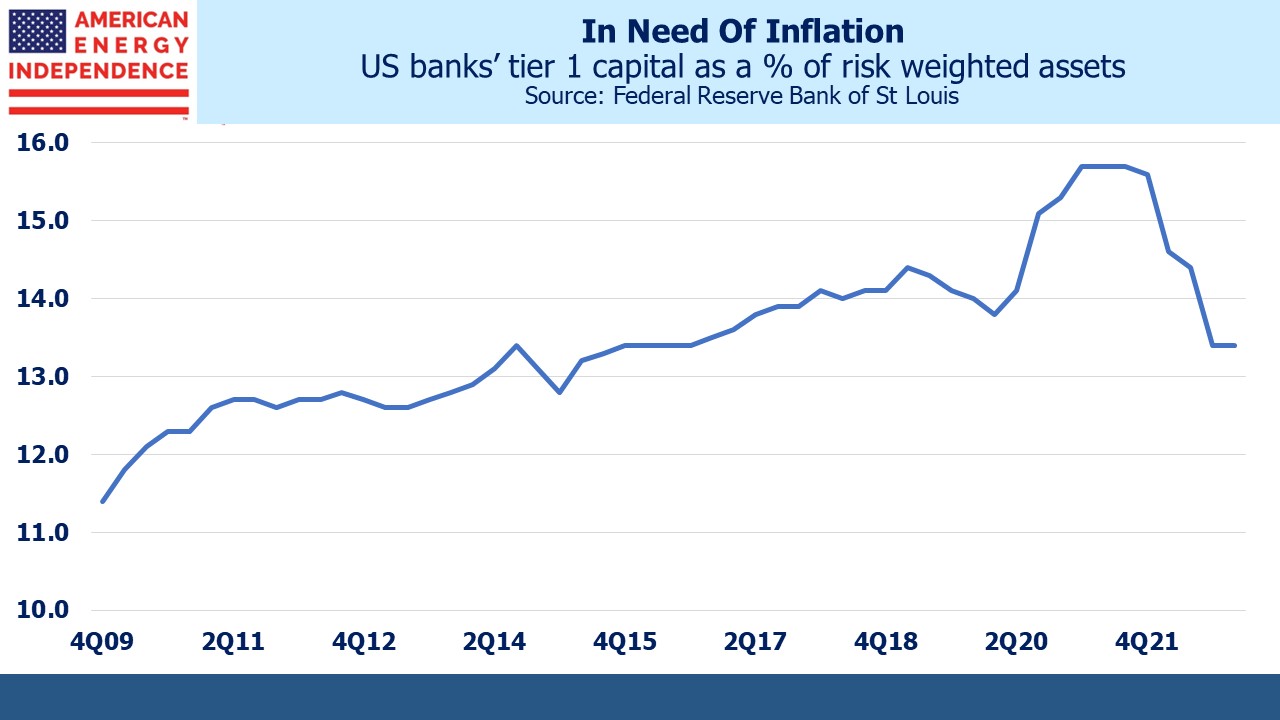

Inflation is the friend of the inveterate borrower. It reduces the real value of obligations. Our fiscal outlook will benefit if debt growth lags nominal GDP. Low interest rates, especially negative real rates, help. 4% inflation leaves more room for real yields to be negative. 2% doesn’t, and as we’re seeing the effort to get inflation back to 2% is making our fiscal outlook worse.

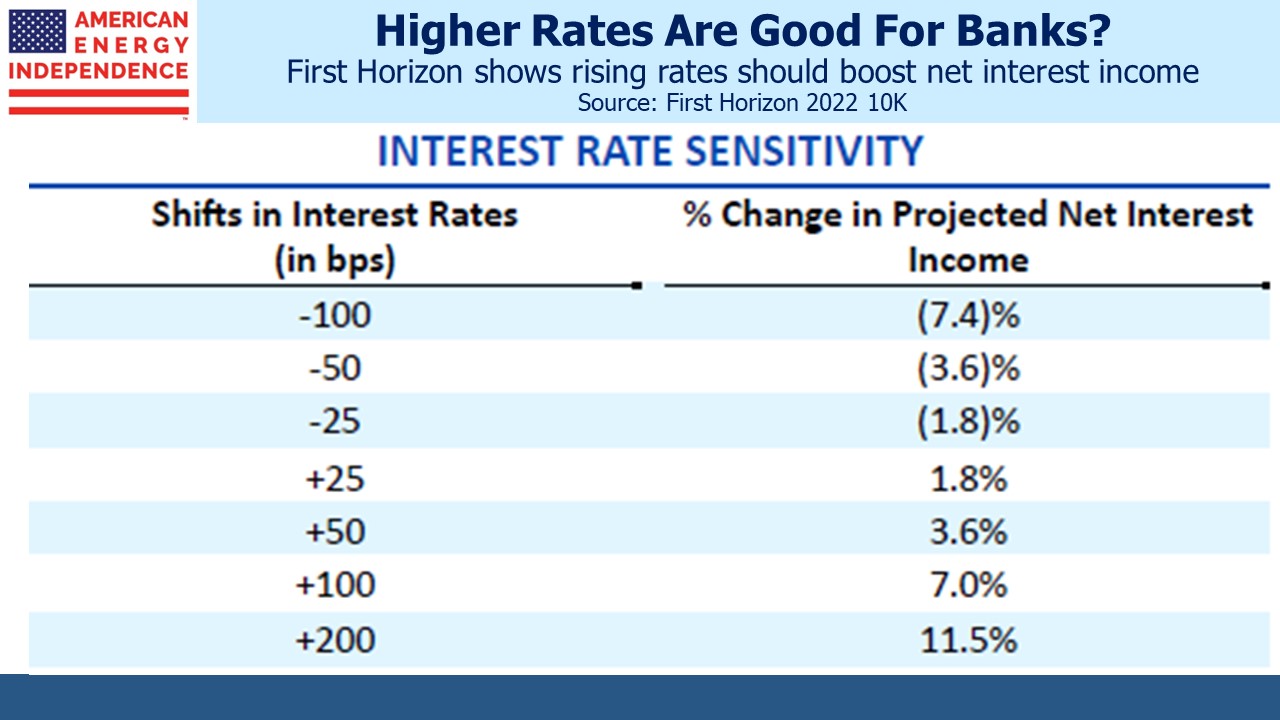

Throughout history governments have eased their debt burden through currency debasement. I explained why this will be America’s solution a decade ago in Bonds Are Not Forever. Developments since then confirm this outlook. There’s little reason to expect spending cuts or tax hikes because there are no votes in it and no apparent cost to current policies. Today’s biggest economic disruption is coming from the Fed’s efforts to restore inflation to 2%. Regional banks and the Federal government need lower rates. There’s a fiscal cost to tight monetary policy.

We can lower inflation or our debt burden. We can’t do both. They are mutually incompatible objectives. We are already learning to live with 4% inflation. It’s not that bad. It’s the path of least resistance.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment: