What’s Your Inflation Rate?

The other day I was chatting with a retired friend about the inflation rate he should assume when analyzing his investment portfolio and its ability to fund his retirement. The Fed’s stated inflation goal is 2%, so my friend felt that 3% was a conservative assumption.

There are several problems with using the CPI to estimate future living expenses, described in prior blog posts (see Why Keeping Up With Inflation Isn’t Enough, Why Inflation Isn’t What You Think and Economists Having Fun With Inflation).

These blog posts and others explain that inflation statistics are based on a basket of goods and services of constant utility. They strip out the quality improvements in the products and services we buy that steadily raise living standards. Simply keeping up with inflation means not participating in the improved quality of life.

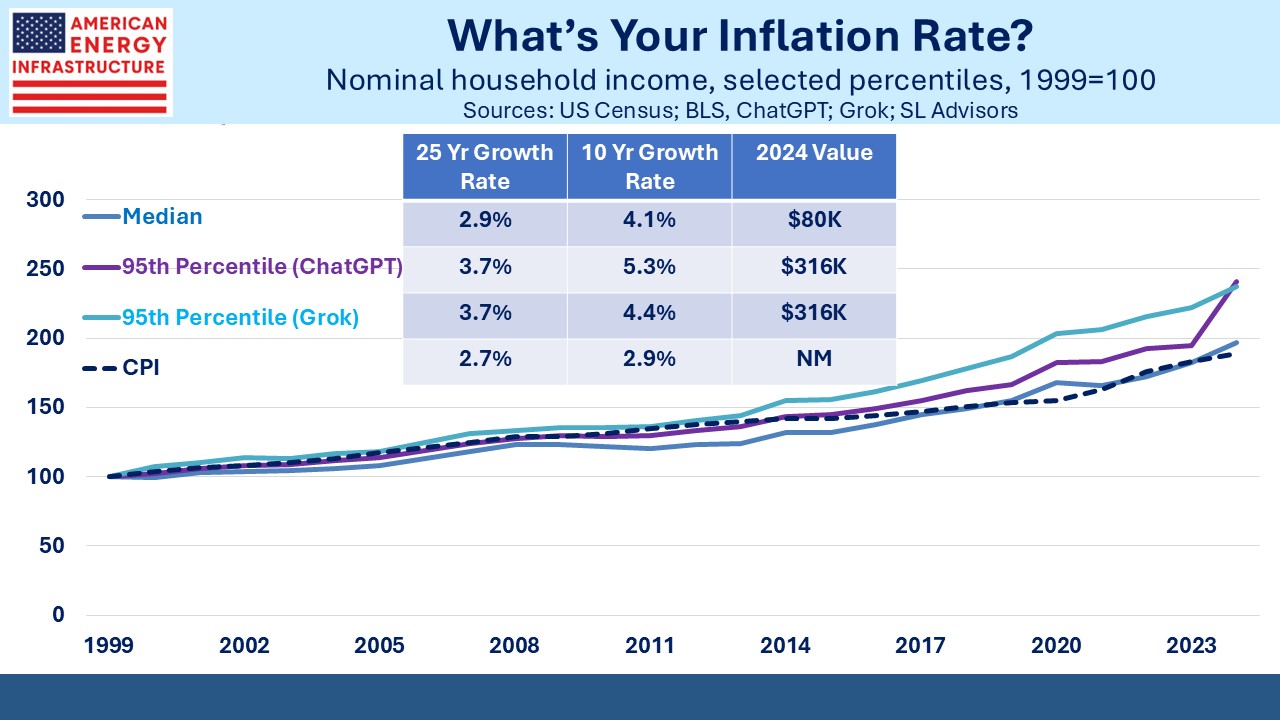

Today’s median household income gives you a better standard of living than the one from a decade ago. Keeping pace with inflation isn’t enough, even though for many retirees that’s a challenging goal after taxes. Assuming your living expenses will grow in line with median household income is a better bet. Over the past quarter century, that’s 2.9%, slightly ahead of inflation at 2.7%.

Readers of this blog are not representative of the broader population. You are on average richer, smarter, older and more politically right-leaning than the rest of the country. And, in my personal experience, unfailingly good company too. You’re well above the median household income. Unfortunately, it turns out that for higher percentiles, income, and therefore you can assume consumption, is growing faster than the median.

My new toy ChatGPT suggests many adjectives for Naples, FL, where we live. I especially like sun-drenched, refined, affluent and idyllic. It is therefore a completely unrepresentative town, and retirees here face an even greater challenge in maintaining their lifestyle.

Income dispersion is increasing, and it is boosting the cost of what 95th percentile households buy faster than the median, and well ahead of the CPI. Dining out, first class airfares, country club memberships and tickets to live concerts are all reported to be noticeably higher than a year ago. Flying private is up 28% since 2020, although not your blogger’s problem. Call it the Naples Conundrum. The higher your income percentile, the higher the inflation rate in your own consumption basket of goods and services.

The Naples Conundrum is a lighthearted way to illustrate an important consideration for anyone in retirement. You should assume that your expenses will grow faster than CPI and at least as fast as household income. You should further consider that increasing income dispersion will make it harder to stay at the same percentile.

The problem has become more acute. Inflation over the ten years to 2024 (aligning with the most recent household income data) was 2.9% versus 2.7% over the past 25 years. Median household income grew at 4.1% (versus 2.9%). But for the 95th percentile it grew at 5.3% (versus 3.7%).

The income data is from ChatGPT, but because different AI models can provide different results, I also looked at Grok which found a 4.4% ten year income growth rate for the 95th percentile of households.

On top of all this, the future retiree needs to consider what our relentless Federal fiscal profligacy means for long run inflation. As this blog regularly argues, the reliable solution to excessive debt has historically been currency debasement through higher inflation. Few would confuse President Trump with a hard money man. His views on Fed policy are well known.

With Federal interest expense over $1TN annually, lower rates could help (see Monetary Policy Is Increasing The Deficit). Higher inflation would better accommodate rates on our debt below inflation (i.e. negative real rates). It’s easy to criticize this as a misguided policy, but what’s important is to assess its likelihood and consequently the impact on inflation and investment returns.

I think 4% inflation is more likely than 2%. If the Fed began targeting stable inflation around 3%, they’d find many economists cautiously supportive.

As far as what a saver should assume for the increase in their living expenses to preserve their relative standard of living, 3% would seem to be the low end of the range. 4-5% is more appropriate.

Some might respond to this by thinking they need to generate higher returns from their portfolio, meaning take more risk. However, this would be flawed thinking. Assets don’t return more just because you need them to. A higher return requirement doesn’t alter the return set available. Adopting a riskier portfolio can also increase the probability of significant underperformance.

For some, delayed retirement and working longer may be the answer.

Alternatively, and as we’ve noted before (see Inflation Protection From Pipelines), midstream energy infrastructure with the prevalence of inflation-linked contracts is, we believe, better situated than most sectors to offer protection against higher inflation.

Think of it as the Naples Solution to the Conundrum.

Last week we had the opportunity to catch up in San Juan, Puerto Rico, with Jerry Szilagyi, owner of Catalyst Capital Advisors our mutual fund partner. We’ve been in business together for eleven years, and Jerry along with his team have been great partners. This summer they’ll be celebrating the company’s twentieth anniversary, and we’re looking forward to being there with them.

We have two funds that seek to profit from this environment: