What Energy Transition?

Daniel Yergin is right to call it the Energy Addition. In an essay in Foreign Affairs called The Troubled Energy Transition, he notes that since 1990 hydrocarbons have dropped from 85% of primary energy to around 80% today. That can hardly be called a transition. Since 2000 global energy consumption has increased from 397 Exajoules (EJs) to 620 EJs.

Renewables, including hydropower, have met only 27% of this increase. They’ve gone from a 7% to 15% share, but Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHGs) have gone from 24 to 35 Gigatonnes.

Climate extremists will argue that without the growth in solar and wind it might have been worse, but the numbers show that the strategy of relying fully on these intermittent sources has been a huge failure. And yet renewables promoters continue to assert that solar and wind are the cheapest form of power generation.

The Biden administration sought a 50% market share for EVs by 2030. It’s currently stuck at 10% and no longer an objective of the Federal government. Every EV owner I know keeps a second car for long journeys. This is hardly a transportation strategy for the masses.

Offshore windpower targeted at 30 Gigawatts by 2030 will be missed by at least half.

As Yergin points out, past energy transitions have never seen the displacement of the old by the new (ie wood for coal). The developing world’s six billion citizens want to use more energy. They’re not going to readily swap coal for wind turbines, and the $TNs in subsidies necessary from rich countries to pay for this aren’t forthcoming.

Promises of abundant cheap renewable energy with well-paid union jobs were an empty promise. Perhaps Biden’s dementia was already affecting his judgment when he spoke those words.

Critics argue that prolonging the use of natural gas risks embedding its use and GHG emissions in our energy systems for decades to come. Bill Gates made this flawed argument in his otherwise thoughtful book, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster: The Solutions We Have and the Breakthroughs We Need.

But to reject natural gas is to embrace the fantasy that solar and wind will fully replace them. This has led to an enormous misallocation of resources and subsidies to promote energy sources simply inadequate to the task.

Instead developing countries should be encouraged to prioritize gas, which emits around half the GHGs as coal and is a ready substitute for power generation, heating, cooking and many industrial uses. Emissions will fall, which under current policies they’re not.

There are encouraging signs that commercial choices around the world are pre-empting enlightened policymaking by already moving in this direction. Forecasts for exports of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) continue higher. This is aided in part by Trump’s sensible removal of the LNG export pause imposed by Joe Biden in a desperate move to excite progressives about his re-election. The US is leading The Natural Gas Energy Transition.

The US and Qatar are planning increased LNG export capacity. Russia may even manage to export more following peace with Ukraine, although surely the Europeans will have the good sense to shun such a fickle supplier.

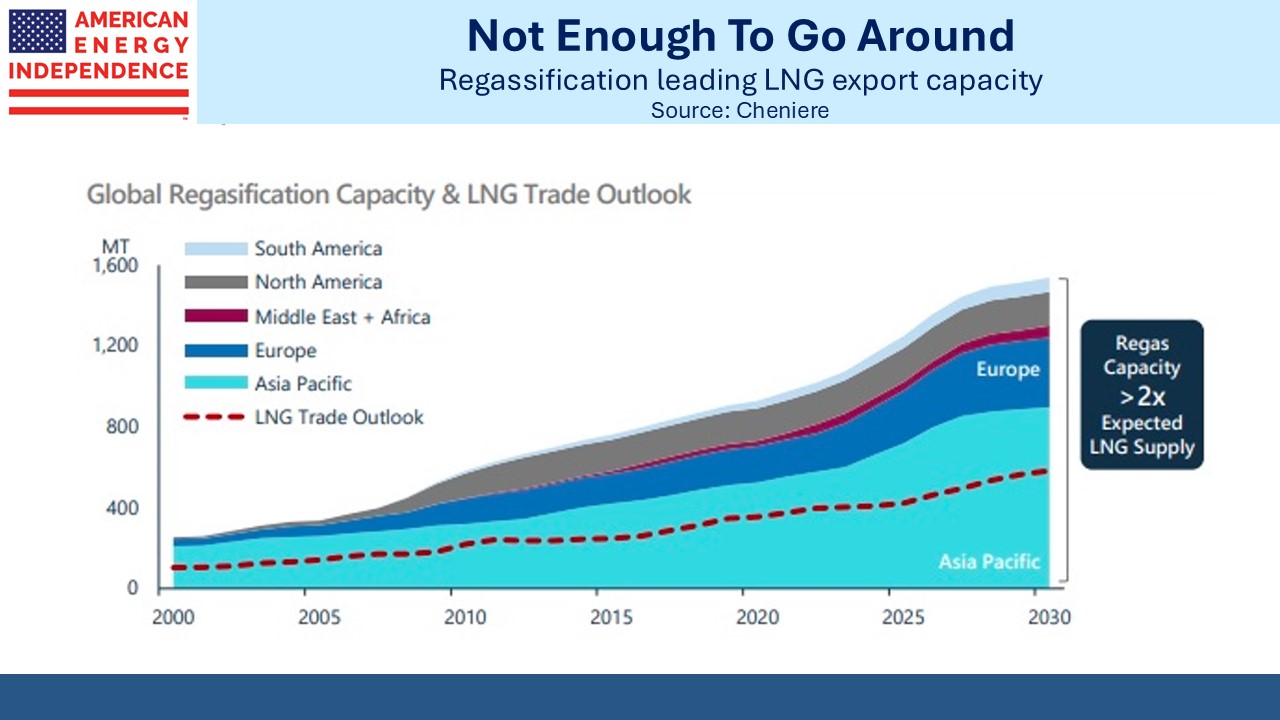

What receives less attention is the growth in import terminals to receive LNG. Natural gas is liquefied to 1/600th of its volume before being loaded onto an LNG tanker. At the other end a regassification terminal restores it to its gaseous form for use by customers.

There are often articles projecting a surplus of LNG in years to come, warning that export terminals will struggle to use all that capacity. Less is written about regassification capacity, which is on track to be twice as big. In other words, if every LNG export terminal projected to be operational by 2030 runs at 100% capacity, only half the regassification availability would be needed. It seems more likely that future LNG exports may yet be inadequate to the demand.

For example, India’s LNG imports from the US reached another all time high last year.

The US has reduced emissions by over 15% in the past fifteen years, mostly by coal to gas switching for power generation. The growth in LNG exports will at least keep emissions below where they would otherwise be and may even reduce them if developing countries take advantage of the opportunity to reduce coal use.

In a few years once Energy Secretary Chris Wright gets his hands on the numbers, don’t be shocked to see President Trump lay claim to being the most consequential climate change president in history. Progressives will be left in stupified silence by such a claim, but it’ll be based on promoting what works, which is natural gas.

We have two have funds that seek to profit from this environment: