US Explores The Limits On Spending

Paul Kennedy’s The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers coined the term “imperial overstretch”. Throughout history, the decline of every great power has coincided with military commitments beyond its means. Such cycles last many decades, and Kennedy’s 1987 book speculated that Japan was the new rising power about to overtake America. That call was spectacularly wrong, but the underlying principles remain valid. After twenty years, almost a $1TN and over 2,300 US military lives lost in Afghanistan, we have little to show for it. America’s humiliating exit from Kabul is not how superpowers conclude military expeditions.

Simple math shows that US military dominance will slowly give way to a multi-power world. War is expensive, and economic size drives success. US share of global GDP has declined from 40% in 1960 to 24% today, as emerging economies such as China have made strides.

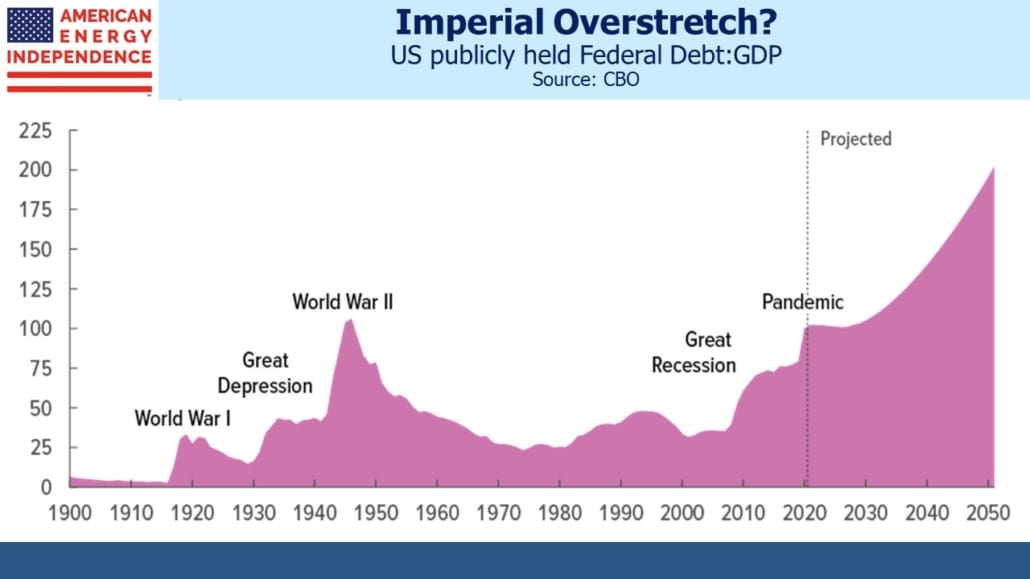

Historically, great powers have begun to decline when they continued to assume obligations inconsistent with their capacity to meet them. Such decisions aren’t inevitable, and the arc of history is long. America remains a great country. But it’s useful to consider episodes such as our recent withdrawal from Afghanistan against our growing debt, set to test all notions of sustainability.

America’s debt:GDP is projected to double in the next three decades, according to the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO). This assumes no new pandemic and no wars, both significant sources of past unplanned spending.

It’s likely we will not acknowledge whatever constraints on our spending this projection should imply. Long term interest rates remain low, helped by the Fed’s monetization of around half of all newly issued Federal debt (see Behind The Fed’s Benign Inflation Outlook).

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is the great enabler (see Reviewing The Deficit Myth, Stephanie Kelton’s book on the subject). It teaches that the only constraint on a government’s ability to borrow and spend in its own currency is inflation. Since the Federal government can always issue bonds to the Federal Reserve with its unlimited ability to create the funds to buy them, we always have a buyer of last resort. If government spending goes beyond the economy’s ability to deliver the goods and services offered, thereby driving up prices, inflation results. This is the only practical constraint on the budget deficit.

Forget about our foreign creditors’ willingness to finance our borrowing. The threat of Japan, or in recent years China, dumping US bonds and causing a recession through sharply higher rates has been periodically raised. It hasn’t happened, and likely won’t. They couldn’t sell $1TN in bonds, and if they tried the Fed would undoubtedly step in to manage the process. Ben Bernanke opened the Pandora’s Box of a greatly expanded Fed balance sheet during the 2008 Great Financial Crisis. Having discovered its power, we will steadily increase the set of circumstances that justify such largesse. The bar will be lowered, because it’s apparently costless to do so.

This is why inflation is likely, because there is no other force limiting our ability to borrow. Today’s deficit hawks have lost influence because their message doesn’t resonate. That’s because it doesn’t fit the facts. Their predictions of fiscal disaster make climate change forecasts look astute. The world is 1°C warmer than pre-industrial times if not obviously much worse for it. By contrast, record low bond yields suggest record indebtedness is harmless.

This serves to further increase the government’s perceived ability to borrow, because both the Administration and the Fed assess the current uptick in inflation to be temporary. It may be so, which will show that borrowing hasn’t yet become ruinous. Therefore, more will follow.

Inflation isn’t correctly measured anyway. Statisticians insist on ignoring the rising cost of home ownership even though two thirds of American families choose to obtain shelter that way (see Why It’s No Longer Enough To Beat Inflation). $40BN a month in MBS purchases during a very hot housing market is finally making some FOMC members uncomfortable. Boston Fed president Eric Rosengren recently said, “If you can’t get housing materials and you can’t get construction workers to come back on site, but we do increase demand for housing, then it doesn’t do much for our employment mandate—but it does increase housing prices more than it otherwise would.”

MMT has quietly become mainstream fiscal orthodoxy. Even proponent and author Stephanie Kelton advocated for a CBO-type scoring of the inflationary impact of spending plans. Instead, we are looking at a $3.5TN budget to be passed via reconciliation with no formal consideration of the possible inflationary consequences. If it doesn’t cause the economy to overheat, such budgetary largesse will become business as usual. Inflation is eventually assured.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.