U.S. Plays Its Foreign Policy Hand Freed From Oil

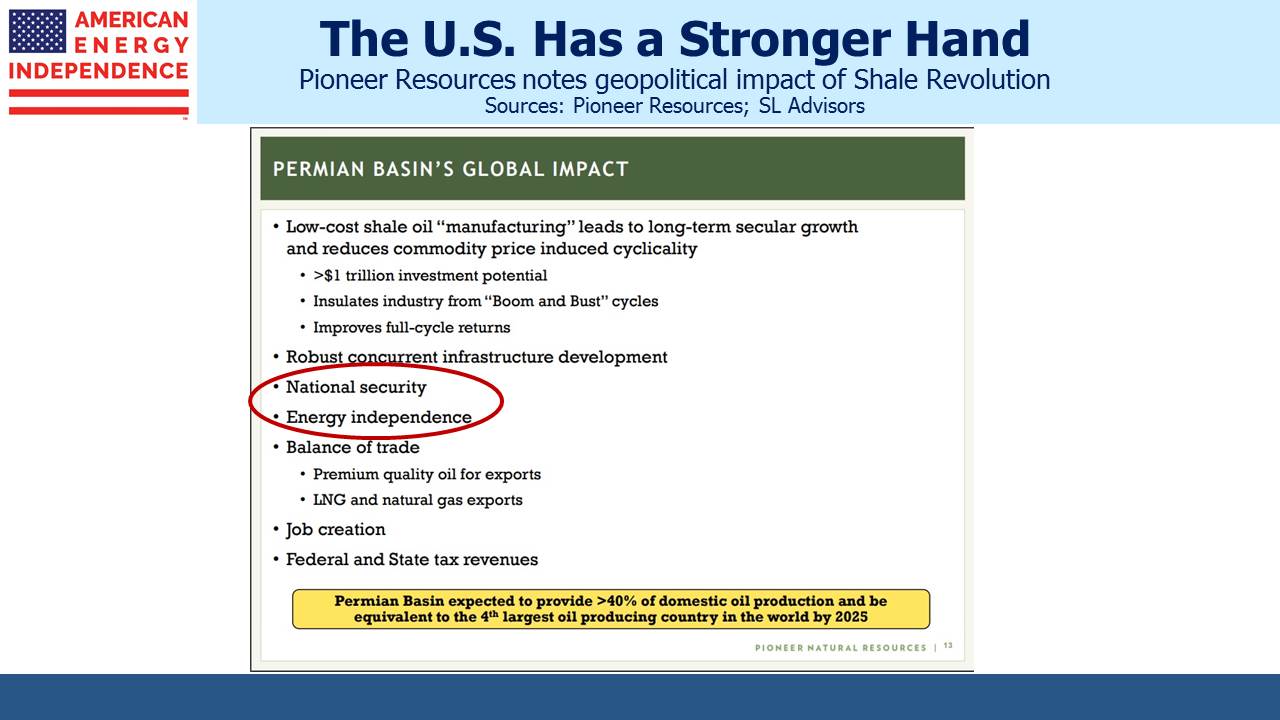

Reports on the Shale Revolution rarely discuss its impact on U.S. energy security, but with little fanfare it’s affording the U.S. greater geopolitical flexibility. The Administration’s decision last week to withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal was made without significant regard to the ensuing reduction in Iranian oil exports. Successive U.S. presidents back to Richard Nixon have called for U.S. energy independence without being able to achieve it. The U.S. is already energy independent on a BTU-equivalent basis (i.e. we produce more energy than we consume in aggregate). We became natural gas independent last year as Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) exports ramped up. We’ve been a net exporter of ethane since 2014, and of propane since 2011.

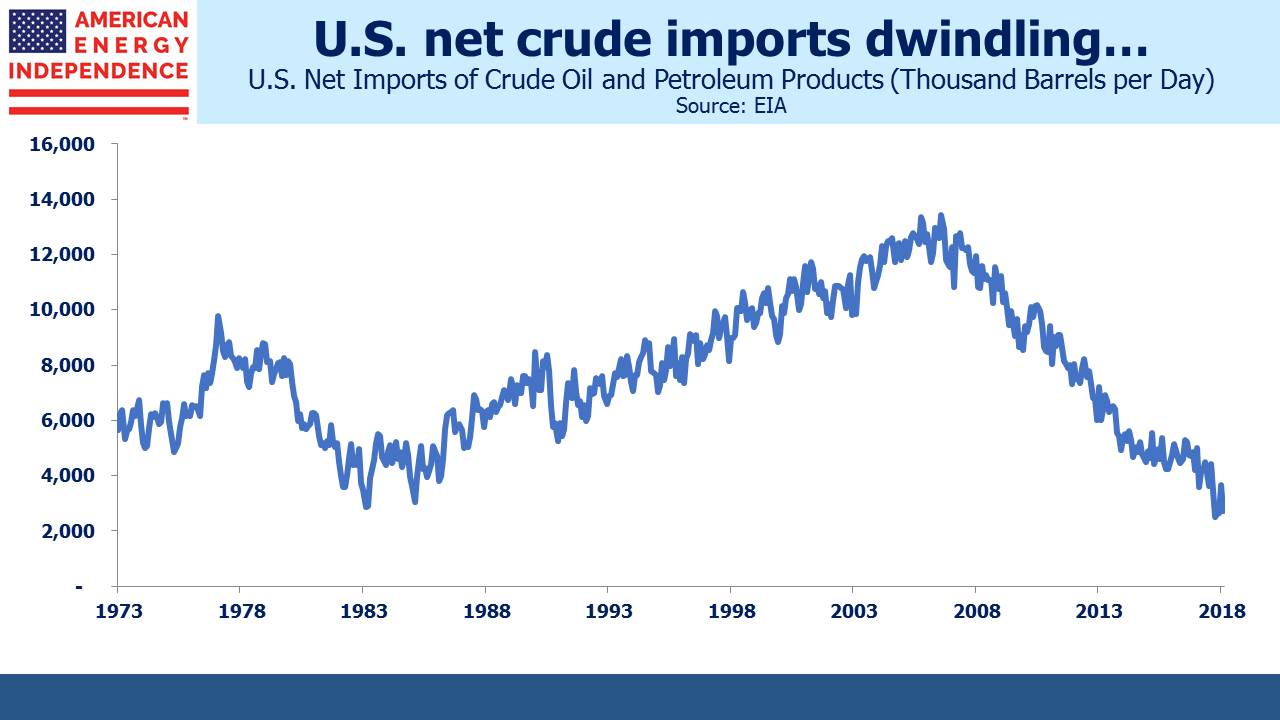

But when a President calls for energy independence – or even energy dominance – he means crude oil. Here, the story is almost as good. In August 2006, net imports of crude oil and petroleum products hit 13.4 Million Barrels per Day (MMB/D). Today that figure is below 3 MMB/D. Even when the U.S. does become a net exporter we’ll still be importing the sour, heavy crude favored by domestic refineries while exporting the lighter grades that are increasingly produced from shale.

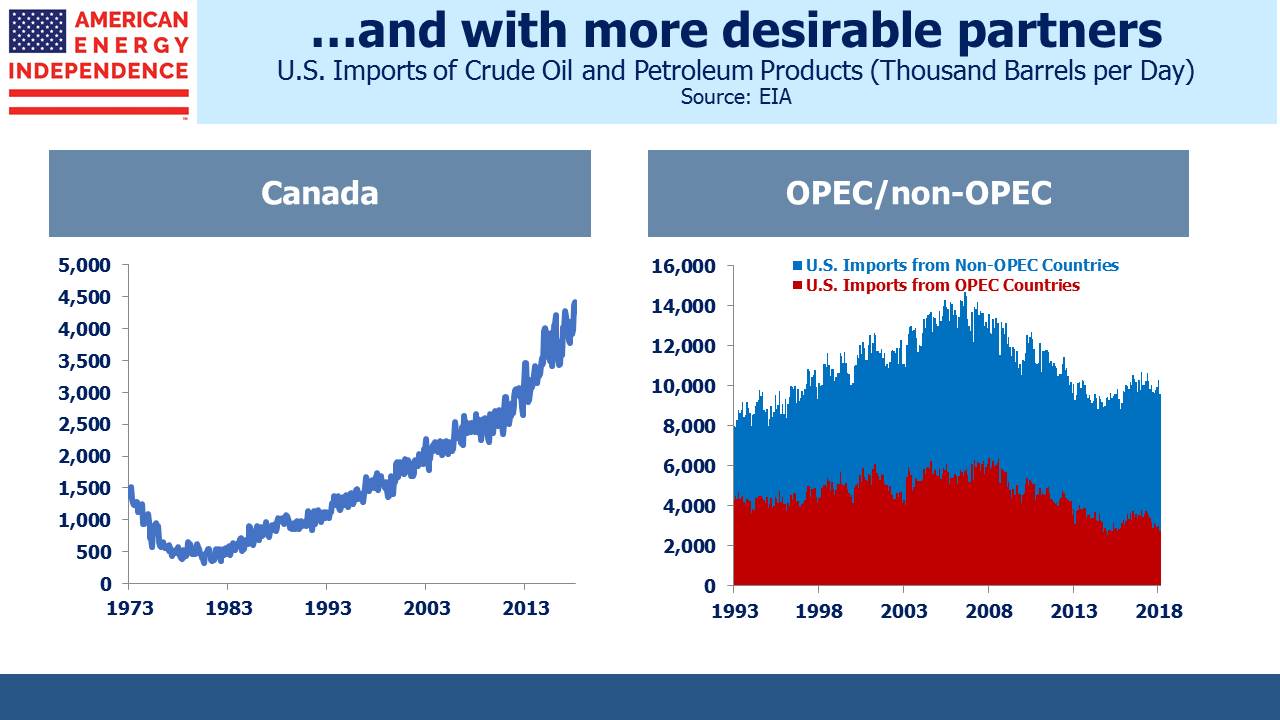

Furthermore, our imports are increasingly from friendly countries. Canadian exports to the U.S. have been rising for years and are currently 4.3MMB/D, while OPEC imports have dropped by 50% in the past decade, to below 3 MMB/D. U.S. imports from Iran ceased entirely during the 1980 hostage crisis and have never recovered. In fact, total trade in goods between the U.S. and Iran was an inconsequential $200MM last year. While Iran is of no economic value to the U.S., the likely imposition of sanctions will constrain Iran’s exports to other countries. The recent rally in crude is in part attributed to fears of less Iranian crude on the global market – they currently produce 3.8MMB/D.

But the U.S. is far less vulnerable to a price spike than in the past. Oil-producing states such as Texas, North Dakota, New Mexico and Oklahoma will welcome the economic boost. Treasury secretary Steve Mnuchin was reported to have discussed with U.S. oil companies ways in which they could raise output, but any decisions are likely to be commercially driven. The Federal government was of little help to the industry during the 2014-16 oil price collapse, and has limited near term ability to influence production levels.

U.S. crude output is responding. Rising prices and falling break-evens are improving profitability, driving output to 10.7MMB/D. Just a year ago, the U.S. Energy Information Agency (EIA) was forecasting 2018 output of 9.9MMB/D, likely 1 MMB/D too low. They now expect 2019 to average 11.9MMB/D. Although growing strongly, U.S. output is insufficient to meet new global demand (~1.5MMB/D) plus offset depletion of existing oil fields (estimated 3-4 MMB/D). OPEC is showing surprising discipline in sticking to their supply agreement. Iran’s exports will likely drop and Venezuela’s production is in freefall. It’s not hard to make a bullish case for oil, and for U.S. companies involved in its production and transportation.

Infrastructure constraints are appearing (see Dwindling Pipeline Capacity Causes FOMO), most visibly in the Midland-Houston crude spread which recently exceeded $15. Wellhead prices can suffer an additional discount of up to $8/bbl to adjust for trucking and shuttle pipeline transportation costs to Midland. Differentials are far in excess of the cost of pipeline transport, because pipelines leaving the Permian in west Texas are full. There are reports that the rail network is clogged with trainloads of fracking sand entering the region, while trucks and truckers are in short supply. Although the logistical challenges offer profit opportunities for the owners of energy infrastructure, in the near term crude output growth may be constrained.

It’s even more acute for Permian natural gas production, which is an associated by-product of crude oil output. On Energy Transfer’s earnings call COO Marshall McCrea predicted occasional days of no bid for natural gas at the Waha hub, a collection point for Permian gas. That’ll leave drillers contemplating flaring of natural gas or shutting in otherwise profitable wells while the infrastructure catches up.

In March, before today’s pipeline constraints had affected price differentials, Magellan Midstream Partners (MMP) dropped plans to add a pipeline that would have moved 350,000 Barrels per Day of crude across Texas, because not enough producers would guarantee to use it. Pioneer Natural Resources (PXD) CEO Scott Sheffield warned the industry, ““Oil has a problem late this year and also in 2020.” He added, “It will teach these producers a lesson that they better sign up.”

In other words, insufficient pipeline capacity is in part down to the earlier reluctance of producers to commit, which discouraged the development of infrastructure that would have been in use today. Smaller firms, often privately owned, are more vulnerable than large ones. PXD has firm transportation contracts in place for their increasing production of oil and gas, a point they highlighted in their recent earnings presentation.

One analyst at Rystad Energy blamed energy infrastructure companies for the bottlenecks, saying they had, “…really missed their opportunity when there was a need for investment in new capacity.” In fact, the multi-year travails of MLPs can be traced to the relentless pursuit of growth projects by management teams at the expense of stable distributions (see Will MLP Distributions Pay Off?). When capital was available and customer commitments forthcoming, new infrastructure was built. Oil producers have surprised many, including themselves, at the volume growth efficiencies have made possible. PXD reports Permian breakevens for producers at under $30 per barrel, and in their 1Q18 earnings report show their own costs at around $19 per barrel.

Thanks to the Shale Revolution, U.S. geopolitical decisions are benefiting from more strategic flexibility than in the past.

We are invested in Energy Transfer Equity (ETE), General Partner of ETP, and MMP