The U.S. Borrowing Pandemic

Ever since the 2008 financial crisis ushered in permanently low interest rates, perhaps the biggest question in finance has been why long term rates remain so low (see Real Returns On Bonds Are Gone). On Monday, the U.S. Treasury announced plans to issue $2.99 trillion in marketable debt this quarter, and $4.5 trillion this fiscal year. The second quarter sum alone is more than double what we borrowed last year.

Given the sharp drop in yields, there’s evidently no shortage of buyers. Corporations have been eager to borrow money too. Apple had $94BN in cash and marketable securities as of the end of March – and yet they borrowed $8.5BN in the bond market on Monday. Liquidity is king. At Saturday’s virtual annual meeting, Warren Buffet mused that the $137BN in cash held by Berkshire, “…isn’t all that huge when you think about worst-case possibilities.”

The most fundamental responsibility of a corporate treasurer is to ensure adequate liquidity for any plausible scenario.

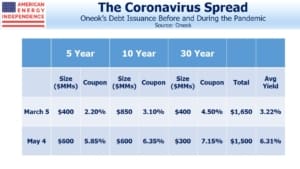

Oneok (OKE) offers an interesting example, because they tapped the bond market for $1.65BN in early March, and just returned for $1.5BN this week. Like most pipeline companies, cuts to spending on new projects exceed their estimated drop in EBITDA. This cash is going to be held, and hopefully not needed. It’ll sit in treasury bills, partially answering the question of who’s going to buy all this new debt the U.S. is issuing.

The negative spread between OKE’s 6.31% blended cost and the 0.10% yield on treasury bills will cost $93MM annually. The $8.5BN Apple raised will also sit in treasury bills alongside the $94BN they already have. These are both small components of the cost of uncertainty.

The Federal government’s fiscal and monetary response has been appropriately massive. They’ve been so effective that Berkshire Hathaway was unable to negotiate any expensive, emergency investments.

The cost is rapidly mounting. Excessive caution was justified in the early days of the pandemic. Hospitals in New York faced the real threat of being overwhelmed, so shutting the economy down to “flatten the curve” was expedient. This has transitioned to a strategy of suppression, with a less clear exit but an increasingly visible and staggeringly big cost.

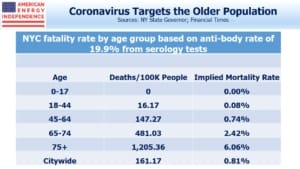

Fatality rates based on known cases reflect the 2% of the population that’s been tested, and people are often infectious without showing symptoms. Data increasingly shows Coronavirus to be highly contagious but with a fatality rate in the ballpark of the flu for those that are young and otherwise healthy. For those between 18-49 years of age, the flu has a mortality rate around 0.02%. Coronavirus anti-body tests are revealing substantial portions of the population to have been already infected. New York City estimates a 19.9% citywide rate. Combined with the city’s fatality rate of 161.17 per 100,000 population, this suggests the fatality rate may be close to 0.81%, skewed towards the elderly.

The vulnerable are well known; 96% of New York City patients hospitalized for Coronavirus had additional health issues, often obesity, diabetes or a heart condition. Dr. Scott Gottlieb, a former FDA commissioner regularly on CNBC, said mitigation hasn’t worked, “as well as we expected.” The virus isn’t going away anytime soon.

Suppression can only go so far. We’re going to have to adapt to the virus. The data suggests people under 44 have extremely low risk, but lockdown strategies rarely differentiate based on risk factors. Targeted stay at home orders for older people and those with health vulnerabilities would allow a return to more normal economic activity, arresting the spiraling debt with little increased health risk. We accept 38,000 road fatalities annually, which could be reduced with lower speed limits. Society already makes these tradeoffs.

Few of us are epidemiologists, and deferring to the experts was correct at the outset. But given the huge economic impact and $TNs in Federal spending, we’d all better do our best to become better informed. It’s correctly becoming a political issue.

We are invested in OKE