The Market’s Too Relaxed About Interest Rates

Mohamed El-Erian maintained his criticism of the Federal Reserve, with an op-ed on Monday morning (see Fed and ECB still behind the inflation curve). It’s remarkable that the ECB’s “hawkish pivot” simply resulted in a fourth quarter tightening no longer being off the table. The Fed meanwhile moves ahead in their predictable fashion even while their predictions about inflation are wrong.

It’s easy to criticize the Fed’s delinquent normalization of policy, but also worth acknowledging that they have engineered a booming economy with full employment, rising asset prices and unmet demand for almost everything. It seems churlish to complain about inflation under such circumstances – given the labor market, many workers can simply demand higher pay to compensate for rising prices.

Last Friday’s employment report showed that’s roughly happening – average hourly earnings for all employees rose 5.7% over the past twelve months. A week earlier, the Employment Cost Index (ECI), which is released quarterly, showed compensation of private industry workers rose 4.4% last year. Pay increases across groups ranged from 3.5 percent for management, professional, and related occupations to 7.1 percent for service occupations.

CPI inflation is running at 7%. Without food and energy, it’s lower at 5.5%, but excluding these now makes little sense because everybody uses energy and eats. These two components can swing around which is why economists like to exclude them, but currently they’re going up like everything else.

Some will always find reasons to be despondent, but asset prices and employment are high while interest rates remain low. The drop in labor force participation is partly due to higher than average numbers of new retirees, enabled by swollen 401Ks and downsizing to a smaller home on better terms than they ever expected. A more popular president would be emboldened to quote Britain’s former PM Harold MacMillan, who in 1957 said his countrymen had, “never had it so good.” Hold on to this economic moment – it will one day be a fond memory.

Economic orthodoxy dictates that we embrace the hair shirt of higher rates as penance for such good economic fortune. So we will. But the Fed will need to create a headwind to all these positives long before inflation is back down to its 2% target. It’s implausible that this will happen without short term rates moving above 2%. Being a Fed critic is satisfyingly self-indulgent, but not as useful as figuring out how to profit from their actions.

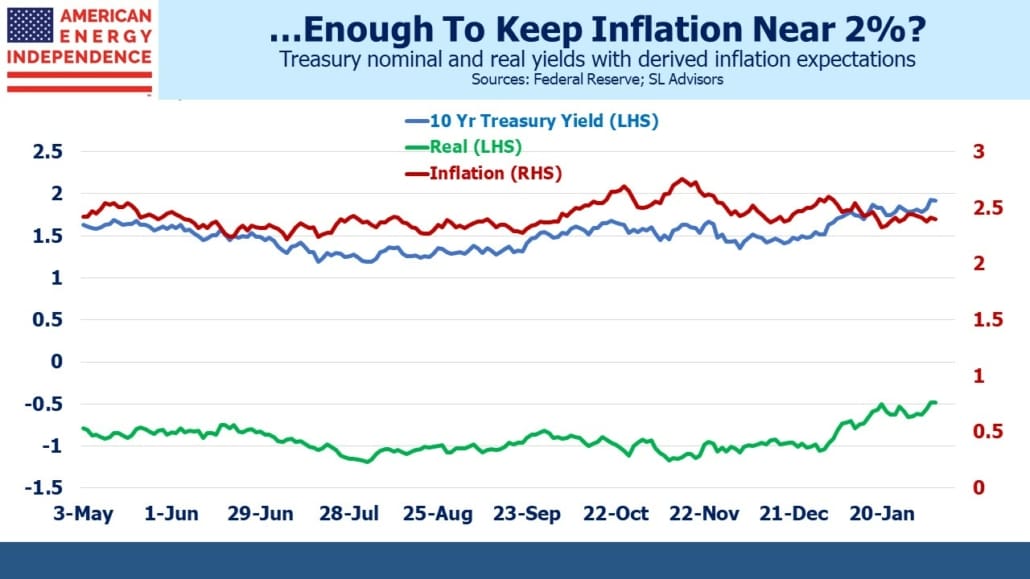

Last month in Why You Shouldn’t Expect A Return To 2% Inflation we noted the incongruity of well-contained ten year inflation expectations with a modest 2% rate cycle peak, all as derived from the bond market. The yield curve hasn’t shifted much since then – an ECI report slightly better than expected was later neutralized by the strong payroll report.

Today’s FOMC interprets its dual mandate of maximizing employment consistent with stable prices in a way that is more risk-tolerant of inflation while more desirous of seeing everyone employed. Americans’ willingness to tolerate a Fed-induced slowdown in pursuit of price stability is untested in over 30 years. Fed chair Jay Powell often says, as he did last month, “We will use our tools to support the economy and a strong labor market and to prevent higher inflation from becoming entrenched.”

For now, Biden has provided political cover for the Fed by endorsing their long-awaited policy shift. Nonetheless, it’s easy to imagine Powell’s Congressional critics once unemployment starts to rise: coping with 7% inflation is bad enough when you’re employed, but harder when you’re out of work.

We’ve been warned for decades that fiscal profligacy will lead to disaster, and so far Stephanie Kelton’s Modern Monetary Theorists are winning that debate (see Reviewing The Deficit Myth). Why is 2% inflation any more vital to our economic wellbeing than a Debt:GDP ratio below 100%? We’ve already abandoned the latter with no apparent consequence.

AOC and her squad are ready to pounce.

Esther George, President and CEO of the Kansas City Fed, gave a speech recently in which she cited research showing that the Fed’s bulging balance sheet is depressing long term bond yields by as much as 1.5%. Take away that support, and ten year treasuries would yield almost 3.5%, forecasting a rate cycle peak easily above 2%. The presence of such support limits the impact of rising short term rates on the economy, requiring an even higher cycle peak than would be the case if the Fed’s balance sheet was back at pre-2008 levels.

The actionable trade is to bet on a higher cycle peak – shorting treasury securities or eurodollar futures with a three to five year maturity is the most efficient. They should eventually price in a Fed Funds rate of 2.5-3%. If by then the economic pain is audible in Congress, tolerance of 3% long term inflation will start to look more likely than a 3% overnight rate. But one or the other is assuredly coming – and probably both. This week’s CPI report may be a catalyst.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Please see important Legal Disclosures.