Saturday`s Attack Is A Game Changer

Early analysis of the twin attacks on Saudi Arabia’s oil infrastructure has focused on the length and severity of supply disruption. 5.7 Million Barrels per Day (MMB/D) of lost output is the biggest supply drop in history, although its impact will depend on how long it takes to repair the damage.

This misses two more important results: (1) the physical vulnerability of Middle Eastern energy infrastructure, and (2) the increasing odds of regional conflict.

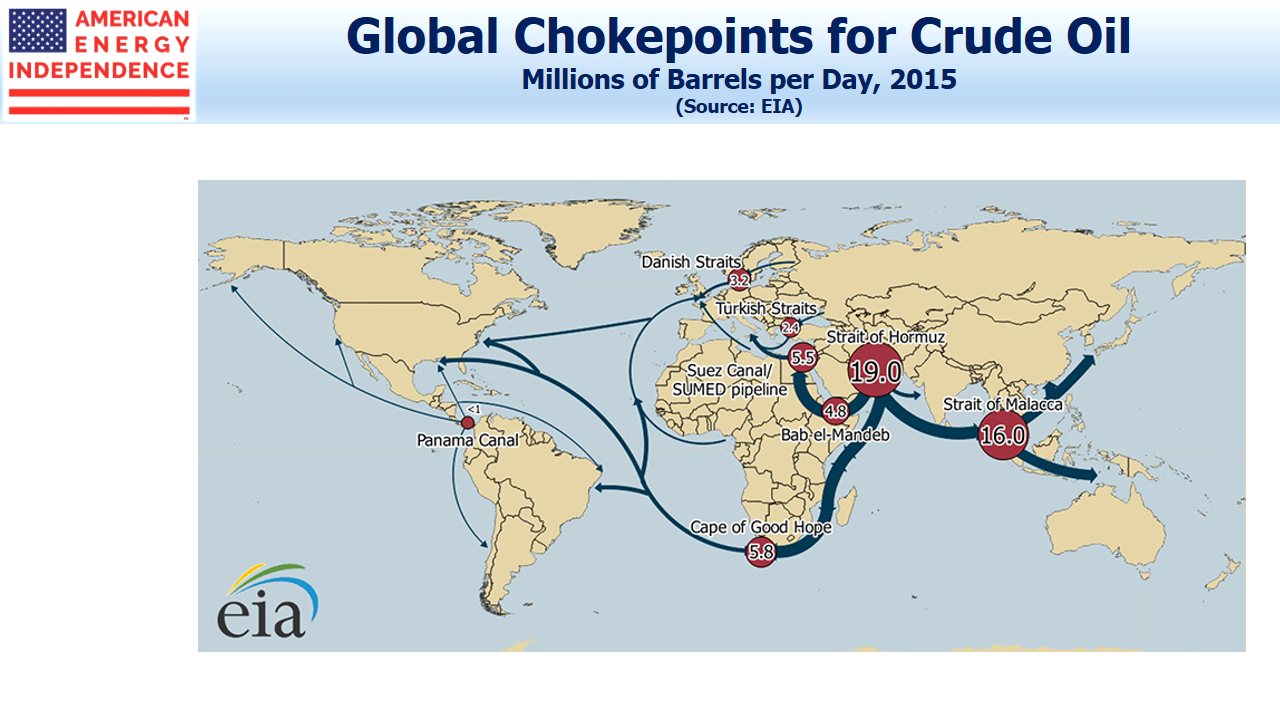

The attack laid bare Saudi Arabia’s inability to defend itself or even intercept enemy drones traveling through its airspace. This is an embarrassing failure of the Saudi military to protect the kingdom’s vital infrastructure. Buyers of crude oil will need to consider the ability of suppliers to deliver on their commitments. A substantial portion of the world’s energy comes from unstable regions, and Saturday’s attack showed that it’s possible to create significant disruption by targeting chokepoints in the supply chain (Investors Look Warily at the Persian Gulf).

It’s not just crude oil that’s at risk, although that is the current focus. Qatar is the world’s biggest exporter of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG), sending around 10 Billion Cubic Feet per Day (BCF/D) through the Straits of Hormuz, 25% of the global LNG market. The five biggest export markets are in Asia, where 75% of LNG trade takes place.

The risk of disruption to LNG and seaborne crude trade is now higher. At the margin this all makes Middle East sourced hydrocarbons more expensive and less reliable. Higher maritime insurance, additional storage in case of supply disruption and all the related risks of doing trade in a region sliding towards open conflict will require market adjustment.

By contrast, the U.S. energy sector is a clear winner. Its infrastructure is geographically dispersed and protected by the world’s military superpower as well as two oceans. The reliability of American supply suddenly seems a bit more important. Added to that, Canada’s export pipelines connect to the U.S. providing another reliable 3.5MMB/D of oil supply.

U.S. midstream energy infrastructure also has more global importance, since the growing role of the U.S. as an exporter makes world markets more reliant on a producer able to lift production when needed.

The Permian basin, which accounts for most of U.S production growth, is only expected to add about 0.6 MMB/D over the next year, so won’t suddenly produce an additional 1 MMB/D. Sustained higher prices will assuredly lift output over time, but even short cycle shale has its limitations. Large multi-pad wells that are the most economic can take up to a year and a half to bring online.

Markets have not really repriced the odds of the regional conflict spreading to include Iran directly rather than its proxies. We have noted before the link between the pre-1941 embargo on Japanese oil imports and the current embargo on Iranian exports. The problem is that the U.S. is not offering the Iranian regime a clear path out. Since open conflict would be disastrous, Iran is pursuing asymmetric conflict with plausible deniability. Moreover, the shift from mining tankers in the Gulf to attacking oil infrastructure is a clear ratcheting up. Whether intentional or not, this seems likely to provoke a response. Saudi Arabia’s rulers must be considering right now the type of military response required and whether they even have the capability to deliver it alone.

Public support in the U.S. for another major conflict in the Middle East is low, and the Shale Revolution affords us more geopolitical flexibility. But if the U.S. does not take a military role, the vacuum will force other countries to consider their willingness to risk further disruption to the 20MMB/D coming out of the region.

Middle Eastern energy supplies are more vulnerable to disruption that previously priced in financial markets (i.e. Brent-WTI spread). U.S. energy infrastructure has an important role to play in providing secure energy supplies. The Middle East is headed towards more open conflict between two big adversaries.

Markets seem to have focused so far only on the short term disruption and how long Saudi Aramco will need to restore supply – currently estimated at a few weeks, although on the weekend it was said to be only days.

We think this attack requires a significant recalibration of supply security. American energy assets look very attractive.