Pipeline Stocks Defy Retail Fund Selling

Midstream is up 27% for the year as of Tuesday, but investors are showing no irrational exuberance. The North American pipeline sector retains its MLP moniker because MLPs used to be the dominant business structure. Even though it’s now two thirds corporations, the ‘40 Act funds who specialize in the sector are still called MLP funds.

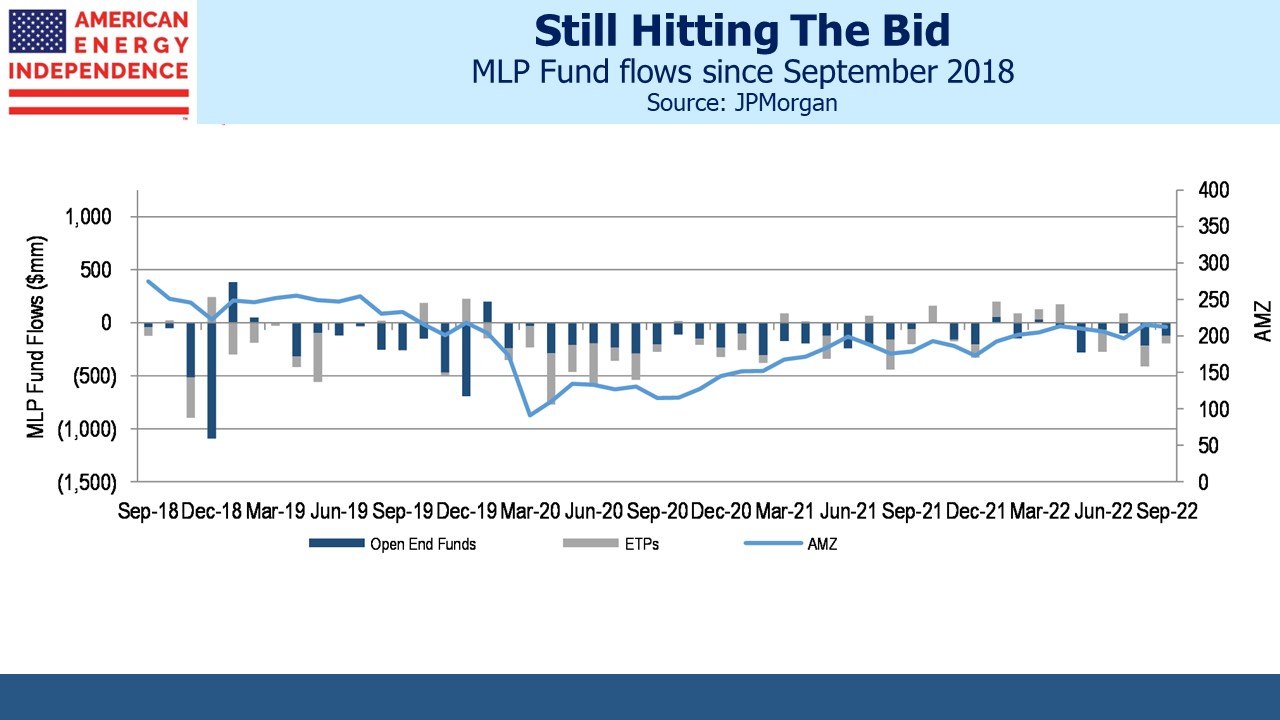

Investors have been exiting MLP funds for several years. JP Morgan calculates that 2016 was the last calendar year that saw inflows. The shale bust led to distribution cuts and saw several big MLPs convert to corporations. They did this in search of a broader investor base but often created a poor tax outcome for their MLP holders. The archetypal K-1 tolerant, US taxable, income seeking investor (ie rich old American) left in disgust. The Covid collapse in March 2020 was, for some, the last straw.

Fund flows are a notoriously poor predictor of performance. Look at the ARK Innovation ETF, where inflows were synchronized with its peak in early 2021. Within a year it had achieved the ignominy of earning a negative return on the average dollar invested (see ARKK’s Investors Have In Aggregate Lost Money).

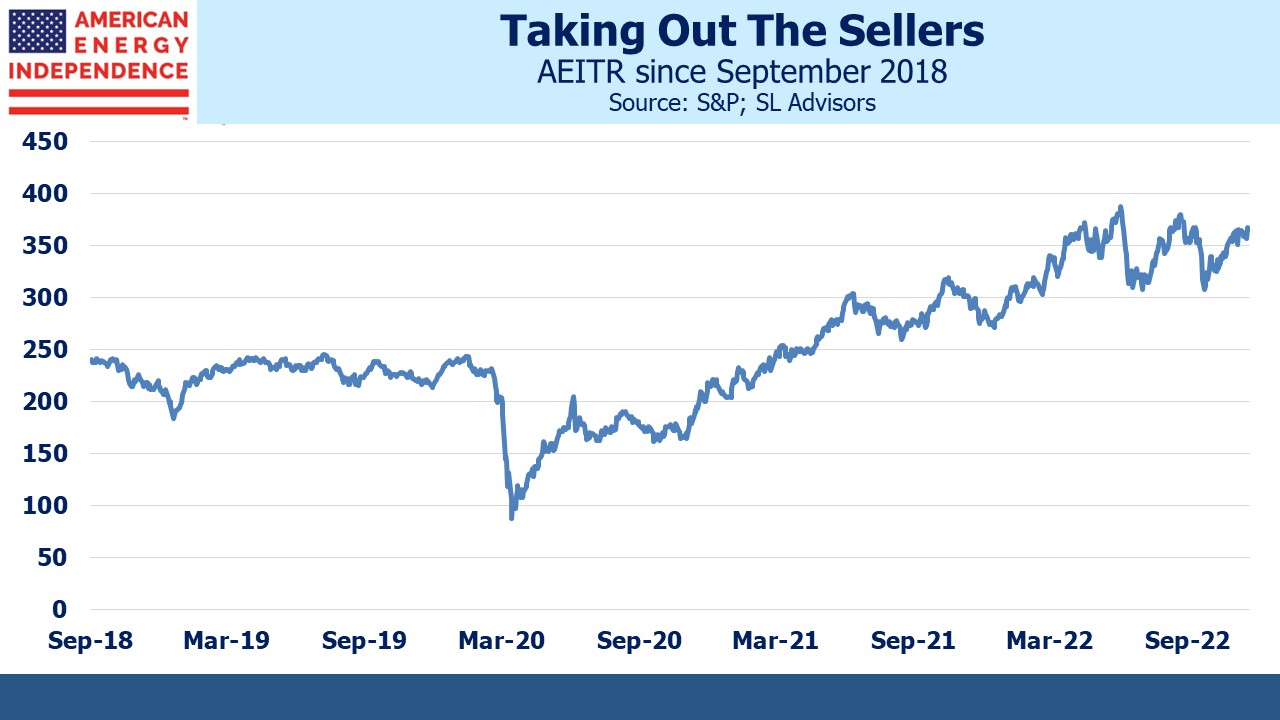

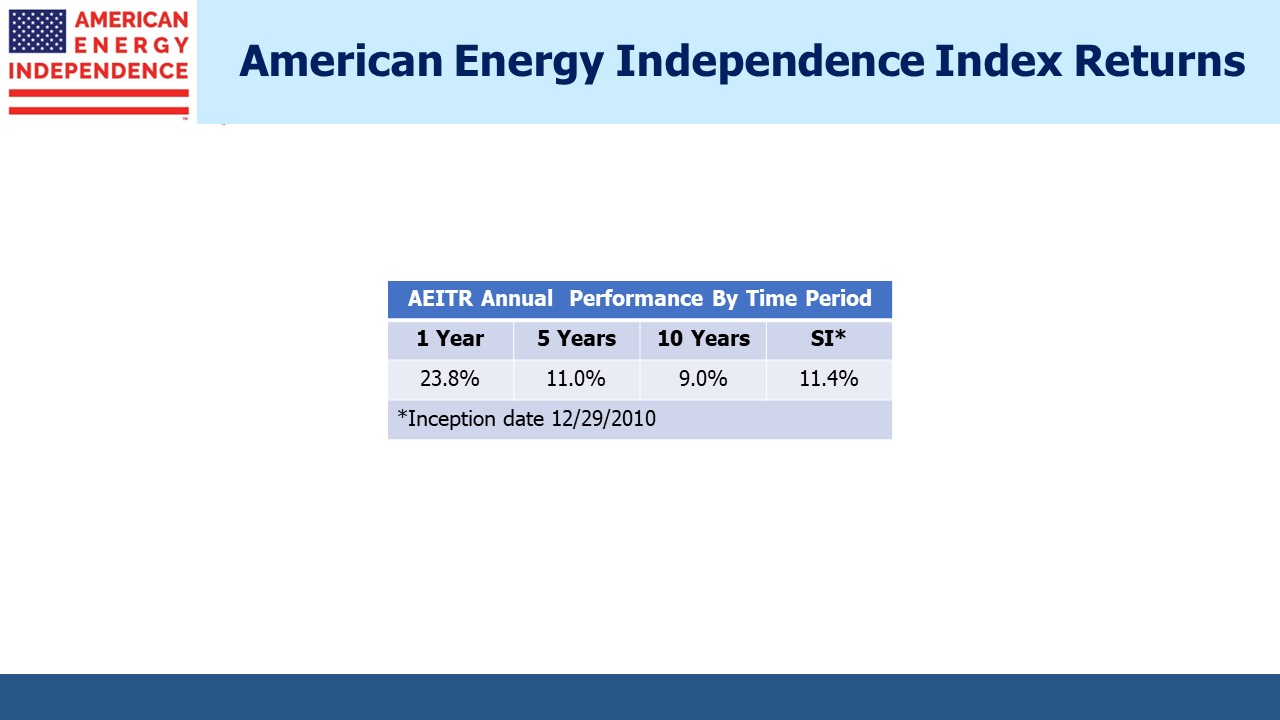

The history of MLP fund outflows coincides with a generally declining Alerian MLP Index (AMZ), but that is misleading because AMZ omits pipeline corporations which are held by the more diversified funds. Since September 2018 (the beginning of the fund flow chart) the broad and therefore more representative American Energy Independence Index (AEITR) has returned 10.8% pa.

The fundamentally bullish case for the sector is familiar to regular readers. However, the positive return despite persistent retail selling of MLP funds is another reason for optimism. If prices are rising when investors are turning away, it suggests that even a cessation of outflows could provide a further boost.

Morgan Stanley calculates that for the first nine months of this year midstream companies repurchased over $3.1BN in stock. This more than offset the selling of MLP funds by retail investors. What could be more bullish than the less informed selling to the better informed?

Investors like the link to PPI inherent in pipeline tariffs. It allows the companies to raise prices in line with inflation, expectations for which have remained surprisingly quiescent. The ten year CPI implied by treasury yields minus TIPs is a remarkable 2.28%. Since the next year will be well over the Fed’s 2% target, investors seem very comfortable that inflation will be back at pre-pandemic levels soon after. The University of Michigan survey provides a slightly different view, with CPI for the year ahead expected to be 5% and 2.9% over the long run.

More consumers report hearing about inflation hurting business conditions, and 43% report that rising prices are eroding their own living standards, up from 20% a year ago. John Williams, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, warned that the unemployment rate could reach 5% as the Fed cools the economy, which would mean around 2.5 million extra unemployed.

With the unemployment rate at 3.7% and inflation just under 8%, the Employment Cost Index (ECI) is rising at 5%. This still leaves many workers worse off in real terms. Greater awareness of inflation as shown in the Michigan survey suggests it will figure more in pay demands as well as spending patterns where half of consumers report cutting back.

Four railroad unions have rejected a 24% pay increase over four years, threatening a strike that could cripple the movement of freight across the US. Congress may force them back to work. The US has a history of legislating against the disruption caused by strikes. In 2005 the New York City transit system shut down for a couple of days over a pay dispute. Under the law, the union leader was sentenced to ten days in prison and the union fined $2.5 million. Workers can strike but not if it causes substantial economic harm, which seems right.

By contrast, in the UK workers on the London underground schedule one day strikes every couple of weeks. An email update sent to travelers in early November breezily advised that there are “lots of public transport options” but added, “There are also some planned strikes taking place over the weekend and into next week.” There is no equivalent legislation that prevents a small group from inconveniencing millions, a significant omission from UK labor law reflecting the country’s liberal leanings.

It’s one reason why UK inflation tends to run higher than in the US.

Upcoming ECI releases will be interesting because pay raises tend to come around year end. Consequently, the December and March ECI seasonal adjustments correct for this and lower the index. The seasonal factors are based on pay increases in a world of 2% inflation. With pay raises running at 5% and the job market robust, it would seem that the ECI could reflect higher than normal pay raises because the seasonal adjustments will be inadequate. Inflation will appear more entrenched, requiring a higher rate cycle peak.

The December ECI is some way off – the September report will be released on December 15th. Inflation won’t return to 2% until workers accept reduced compensation. There’s plenty of reasons to think this won’t happen soon.