Pipeline Bond Investors Are More Bullish Than Equity Buyers

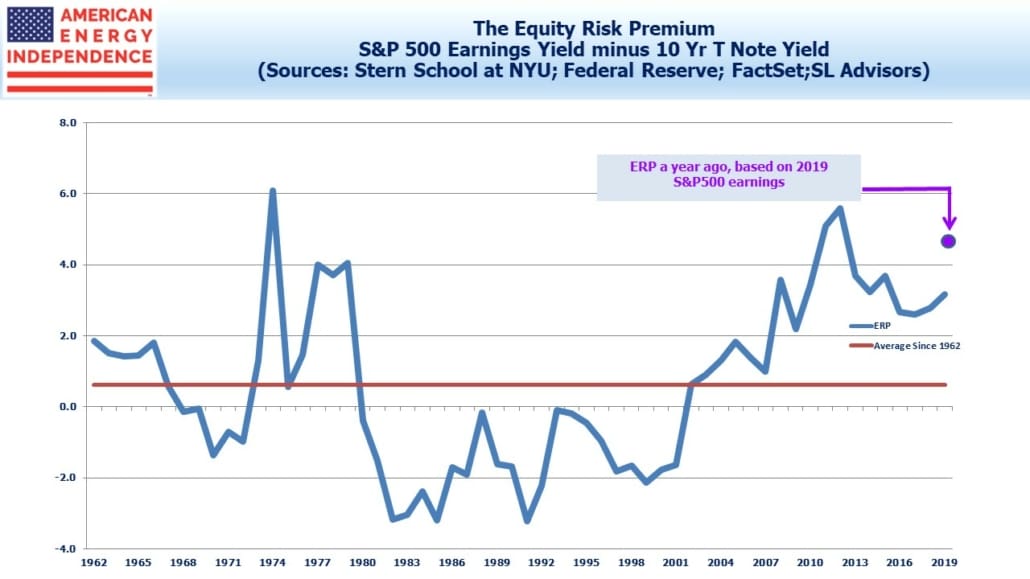

One of the most consistent bullish indicators for stocks has been the Equity Risk Premium (ERP) – the spread between the earnings yield on the S&P500 and the ten year treasury yield. At the end of last year, the S&P500’s 2019 earnings yield was around 7.2% (one divided the P/E ratio, which was then 13.8). With ten year treasuries at 2.8%, the ERP was 4.4, well above the 50-year average of 0.6.

The S&P500 is up 30% this year, and the P/E multiple has expanded to 18X next year’s earnings (i.e. earnings yield of 5.5%). This has brought the ERP down to 3.6 — still favoring stocks, but not as clearly as a year ago. If treasury yields had remained at last year’s levels rather than dropping almost 1%, the ERP would be even lower at 2.7.

Since stocks look cheap, bonds must be expensive. Perhaps the biggest unanswered question facing investors today is why long term bond yields remain so low, and whether this is sustainable.

The return bond investors require over inflation, the real rate, has been in secular decline for thirty years (see Real Returns On Bonds Are Gone). Today’s bond investors are willingly locking in low and negative real yields – in many cases even negative nominal yields. Two compelling explanations are (1) inflexible investment mandates, and (2) fear of another 2008 financial crisis.

U.S. pension funds have raised their fixed income allocation even while yields have fallen, a counter-intuitive response to lower expected returns (see Pension Funds Keep Interest Rates Low). Hard evidence that investors are holding additional low risk assets as protection against a crash is harder to come by, but low yields certainly support that explanation.

Lower real yields on sovereign debt are a result of investors’ strong desire for bonds with negligible credit risk. But the fact that corporate bond yields are being pulled down by these same forces reveals a pricing inefficiency that equity investors can exploit.

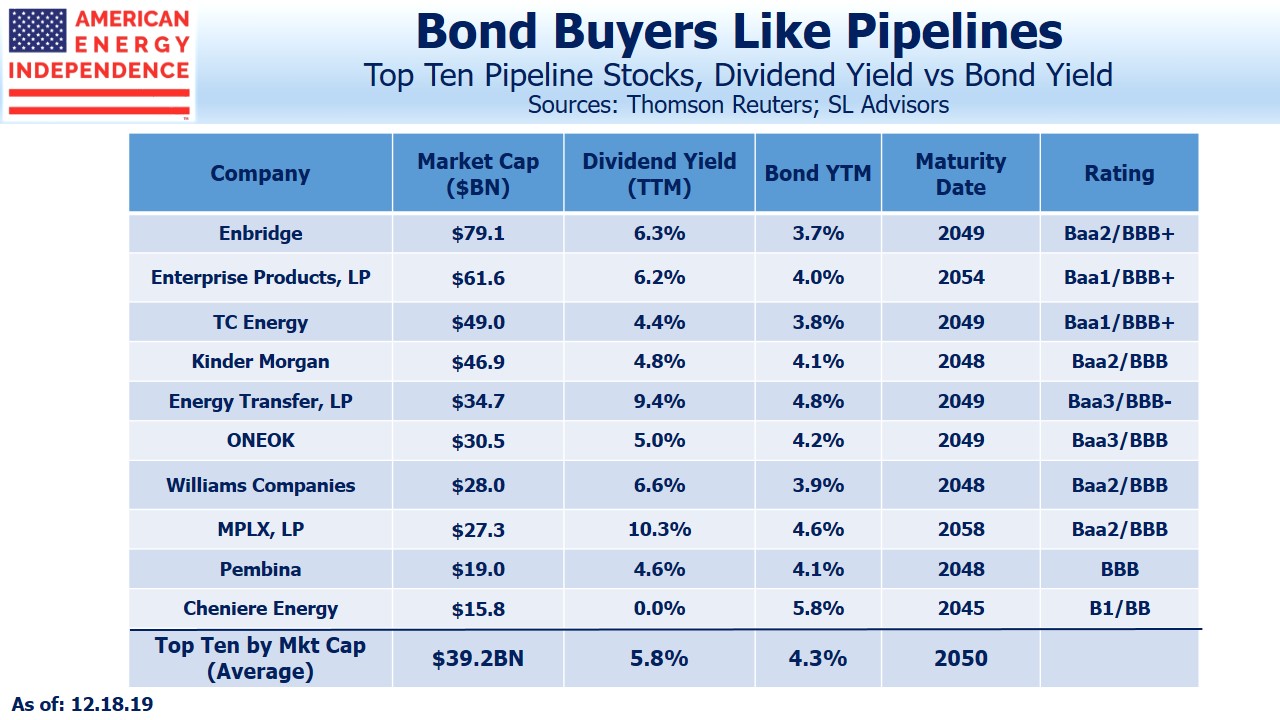

It’s most clear at the individual issuer level, where excessive demand for debt instruments is causing some interesting distortions. The table shows long term bond yields for the ten biggest North American pipeline companies, with an average equity market capitalization of $39BN.

They’re all members of the American Energy Independence Index, the broadest and most representative index of North American midstream energy infrastructure. These ten companies have outstanding bonds with maturities of 25-40 years. They are all investment grade, offering an average yield of 4.3%, which reflects a high degree of comfort with their credit risk over several decades.

By contrast, their equity dividend yields average 5.8%, 1.5% above their bond yields. And this even includes Cheniere Energy (LNG), which doesn’t currently pay a dividend (although they’re likely to institute one over the next couple of years).

Energy has been out of favor more or less since 2014, although stock price performance in December has been strong. These ten companies’ average dividend yield is almost 3X the 1.75% yield on the S&P500, reflecting substantial wariness about their prospects. And yet, bond investors don’t share the same concern.

Equity investors can earn higher yields than bond investors on the same issuer, in addition to enjoying likely earnings and dividend growth in the years ahead. Once equity prices reflect the positive outlook reflected in their long term debt, they’ll re-price higher.

Based on recent performance, that revaluation may already be under way.

We are invested in all the names mentioned above.