Will MLP Distribution Cuts Pay Off?

It’s surprisingly difficult to find out what MLP distributions have been doing. Alerian claims that their index has been growing its payouts at a 6% average annual rate for 10 years, with growth continuing in 2016 (it’s not yet updated for 2017). However, their methodology is odd. They take the trailing growth rate of the current index constituents, which are regularly updated. This tends to bias the growth rate up, because they dump poor performers and add good ones. We examined this in a recent blog (see MLP Distributions Through the Looking Glass).

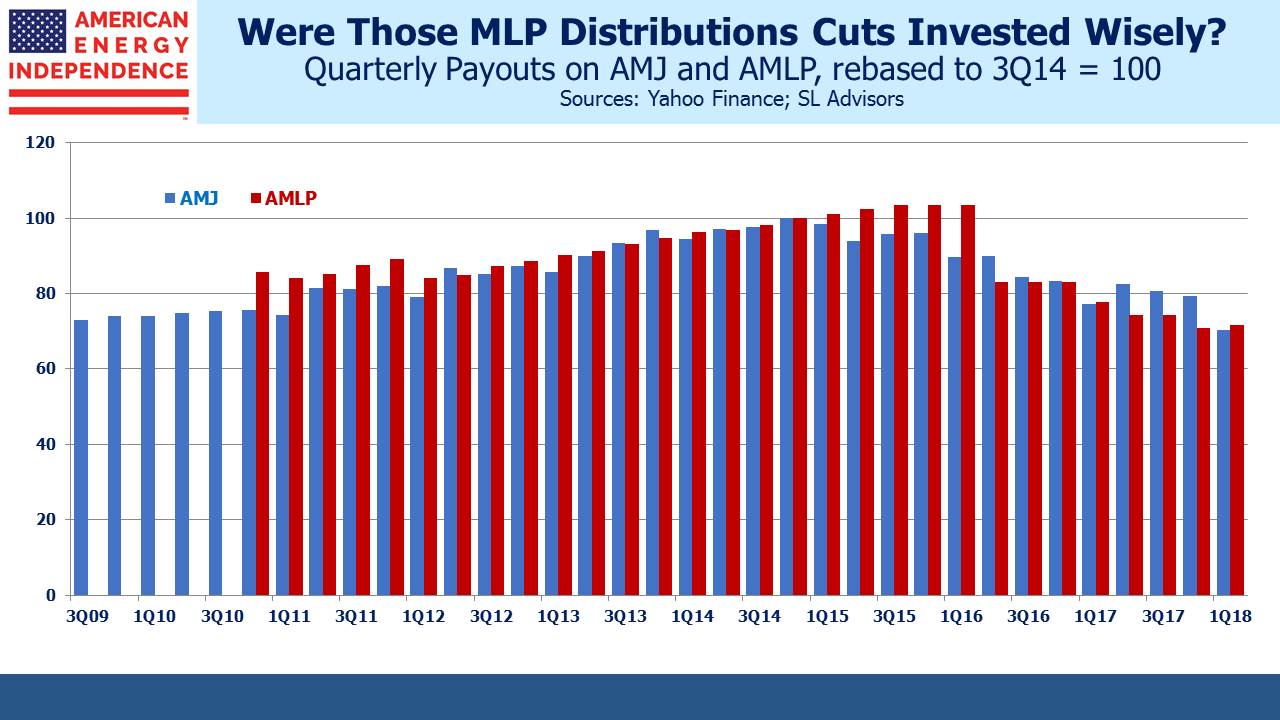

Because Alerian doesn’t publish the actual experience of its index investors, it’s necessary to look at how investment products tied to those indices have done. Not surprisingly, payouts have fallen. As the chart shows, for the JPMorgan MLP ETN (AMJ) and for the Alerian MLP Fund (AMLP), two of the largest vehicles in the sector, dividends are down approximately 30% from their highs in 2014-15. This is what MLP distributions have been actually doing – falling, not rising — in spite of what is sometimes implied. Perhaps coincidentally, the cut in payouts is similar to the drop in the sector (38%) from its August 2014 highs.

As we’ve written before, the Shale Revolution induced many MLP managers to pursue growth opportunities (see More on the Changing MLP Investor). The need for growth capital pressured financial models that historically distributed 90% of Distributable Cash Flow (DCF), when growth needs were minimal. Leverage rose, growth projects were favored over reliable payouts, and distributions were cut. Investors felt let down if not deceived.

Although the big picture is simple, at each company level there are more detailed reasons why growth plans that were not expected to threaten payouts nonetheless led to cuts. Plains All American (PAGP) saw its Supply and Logistics business drop from $900MM in EBITDA to less than $100MM over two years. Kinder Morgan (KMI) was hurt by the cyclicality of its Enhanced Oil Recovery business. But broadly speaking, the dividend cuts were a redirection of cashflows into new projects, rather than reflective of poor operating results.

Over the next couple of years we’ll see if that redirection of cash pays off. The Miller-Modigliani model of corporate finance holds that investors should be indifferent to a company’s capital structure, and should not value dividends (since anybody can create a 5% dividend by selling 5% of her shares annually). Although financial markets don’t always operate that way, the question hanging over the industry is whether these redirected cashflows will eventually deliver their pay-off. If the foregone dividends have been wisely invested, DCF should grow.

We’ve looked at this for the components of the American Energy Independence Index. It consists of 80% corporations and only 20% MLPs. Since many MLPs have converted to C-corp status, energy infrastructure is leaving MLPs with a diminished status. It includes some Canadian companies, since they also operate U.S.-based infrastructure assets and, as we’ve noted, have been rather better run of late than their American peers (see Send in the Canadians!).

Using company data and estimates from JPMorgan, we calculate a two year compound annual growth rate of DCF for this group of businesses of 15%, from 2017 to 2019. Some of these companies were in the Alerian index but left as they became C-corps, some were never in, and some still are. A perfect match is impossible because the constituents of the Alerian MLP index have changed over the years. But that 15% growth rate will significantly support the correctness of those decisions to redirect cashflows from payouts to new opportunities. It won’t be true in every case, and to be sure many investors would have preferred it didn’t happen. But it will provide a form of vindication for managements that increased investment back into their businesses.

The sector has been priced as if the distribution cuts were fully reflective of weaker operating results, whereas in most cases they’ve been to support future growth. Investors appear to be assuming away the foregone distributions, as if the operating cashflows supporting them have disappeared, whereas many companies have been financing growth plans with this internally generated cash. MLP investors are likely not passionate about Miller-Modigliani, but we’ll see in the months ahead whether the theory has worked.

We are invested in KMI and PAGP