Kinder Morgan: Still Paying for Broken Promises

Broken promises aren’t quickly forgotten. That’s the hard lesson being learned by pipeline company managements, as the sector remains cheap yet out of favor.

Kinder Morgan (KMI) reported good earnings on October 17th. Volumes were up, and they sold their Trans Mountain Pipeline (TMX), including its expansion project, to the Canadian Federal government. TMX is Canada’s only domestic pipeline that can supply seaborne tankers. All other pipelines lead to the U.S.

Canada’s landlocked energy resources are becoming a political football. Alberta wants to get its oil and gas to export markets, but neighboring British Columbia opposes the new pipelines necessary for Albertan crude to reach the Pacific coast. Caught between the two provinces, KMI sensibly sought an exit. The transaction was well timed, closing before cost estimates for completing the expansion were ratcheted up and a court ruled that a new environmental study was required (see Canada’s Failing Energy Strategy). Canada’s taxpayers were on the wrong end of the deal.

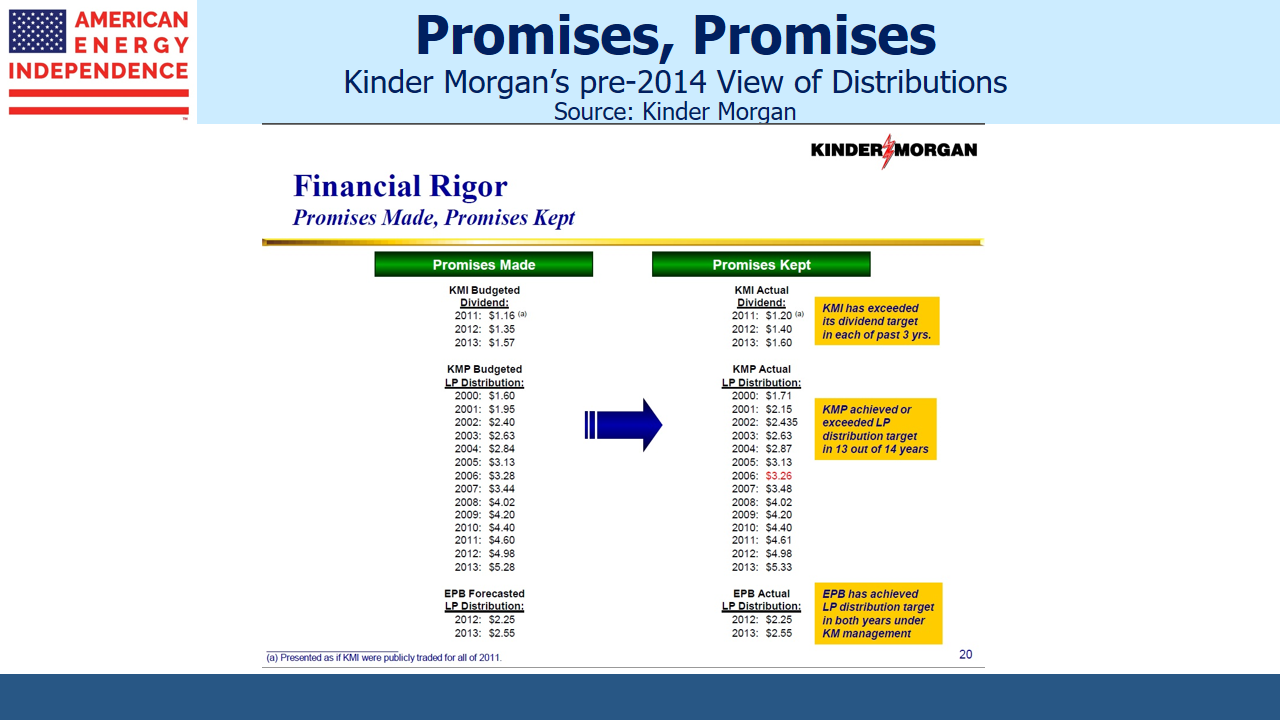

Nonetheless, Rich Kinder opened the earnings call lamenting KMI’s valuation. He said, “I’m puzzled and frustrated that our stock price does not reflect our progress and future outlook.” We do think KMI is cheap, but the explanation lies in recent history. Before the Shale Revolution created the need for substantial new pipeline investments, KMI’s investor presentation reminded “Promises Made, Promises Kept.”

This turned out to be true only until financing new projects conflicted with paying out almost all available operating cash flow in distributions. Investors in Kinder Morgan Partners (KMP), the original vehicle, were heavily abused. They suffered two distribution cuts and a realization of prior tax deferrals timed to suit KMI, not them (see What Kinder Morgan Tells Us About MLPs). Former KMP investors, who are numerous, retain deeply bitter memories of the events and have lost all trust in Rich Kinder.

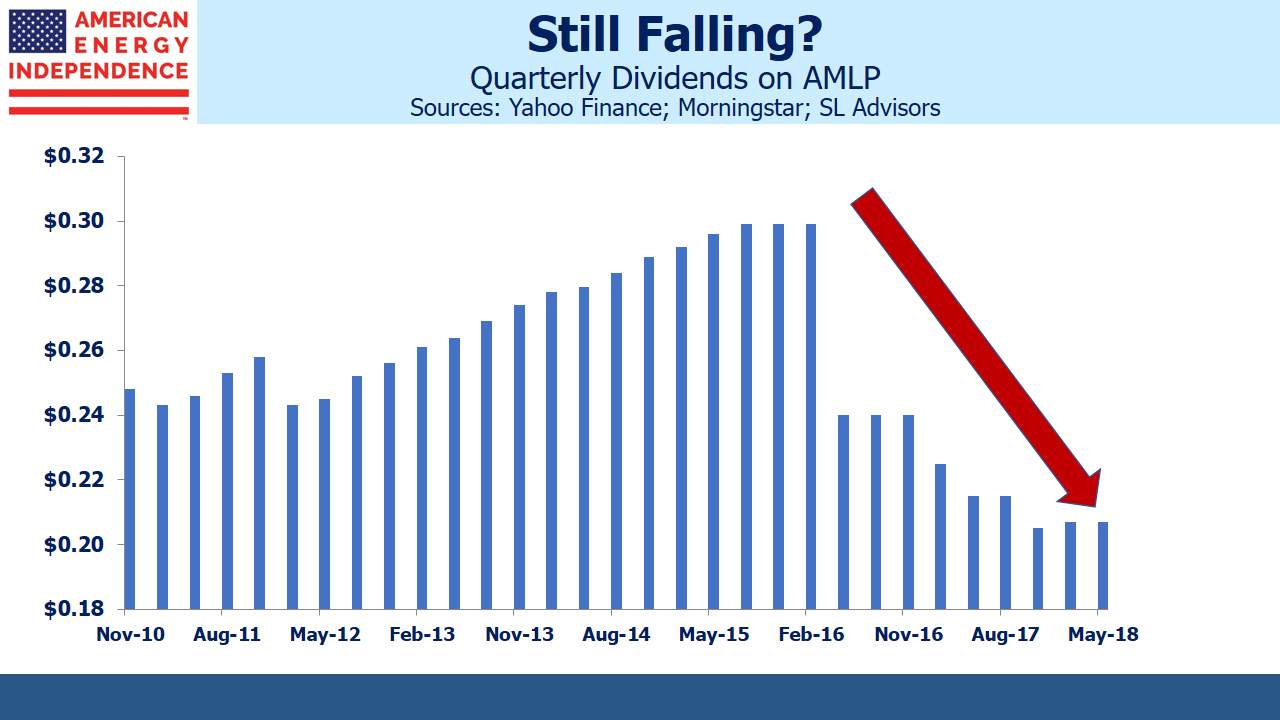

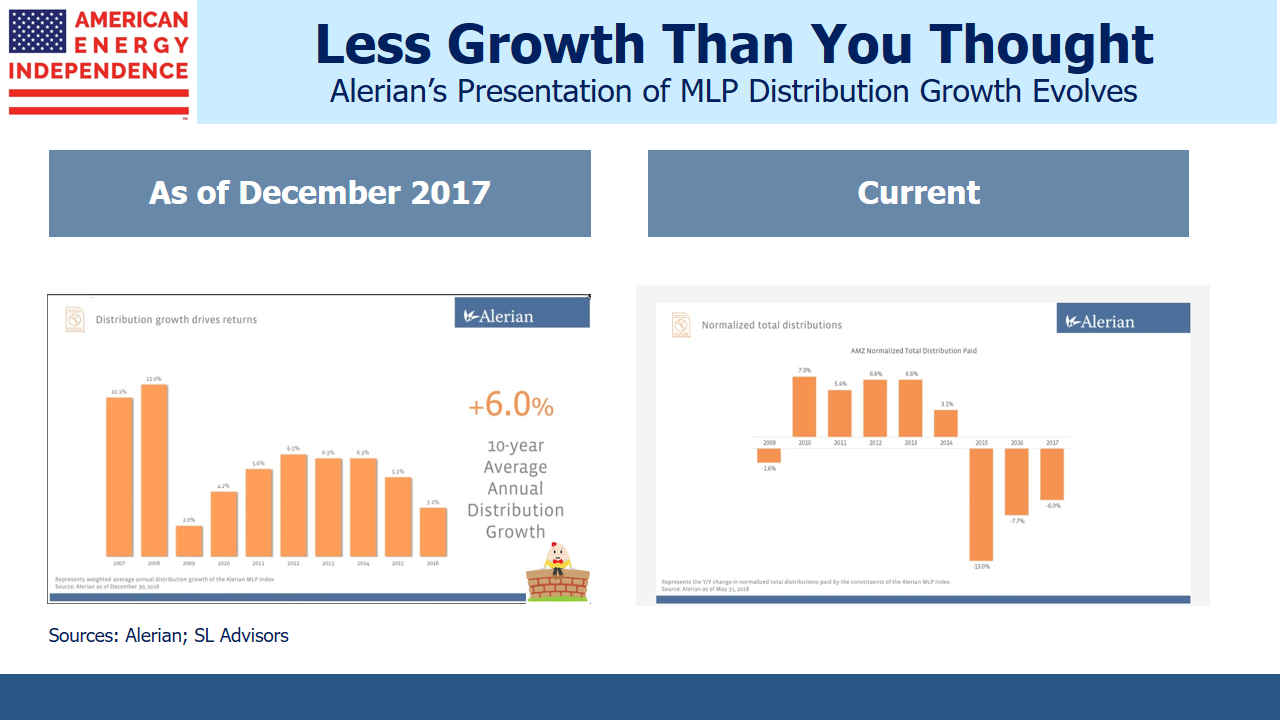

KMI was only the first of many. Distributions on Alerian’s MLP index have been falling for three years. Their eponymous ETF has cut its payout by 30%. Alerian CEO Kenny Feng, normally a reliable cheerleader for the MLP model, recently turned more critical, citing,”…significant abuses of [distribution growth] in the past…” The irony is that until late last year Alerian’s own website showed reliable distribution growth, completely at odds with what investors in their products were experiencing. They only corrected it when mounting criticism from this blog (see MLP Distributions Through the Looking Glass), @MLPGuy and others forced a humbling revision.

Too few commentators acknowledge the poor treatment of MLP investors (see MLP Investors: The Great Betrayal). Pipeline stocks are attractively valued but have been that way for some time. The legacy of broken distribution promises continues to cast a pall. KMI’s objective in abandoning the MLP model was to be accessible to a far broader set of investors as a corporation. So far, it hasn’t helped their stock price.

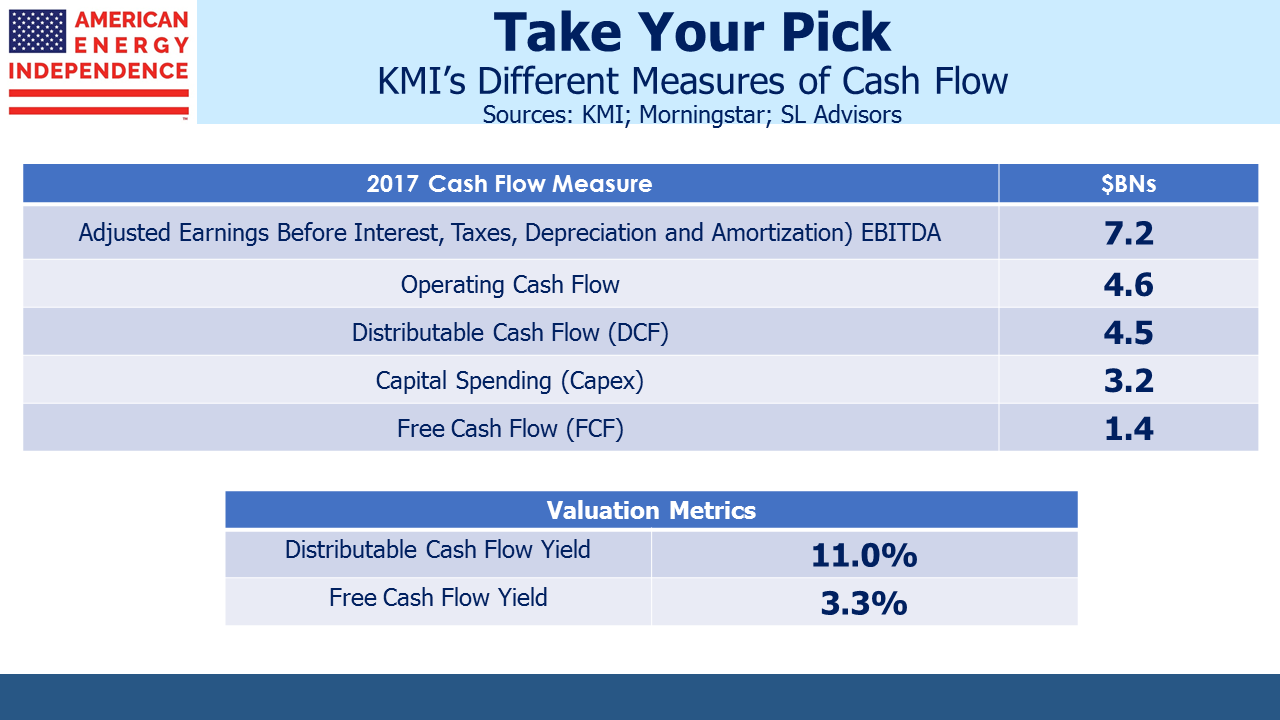

One explanation might lie in how they present their financial results. Distributable Cash Flow (DCF) is a term widely used by MLPs and retained by KMI even after it became a corporation. MLPs calculate their distribution coverage ratio, which is the amount by which DCF exceeds distributions. It’s somewhat analogous to a dividend payout ratio, albeit based on DCF not earnings. Kenny Feng notes that generalist investors aren’t familiar with DCF or its coverage ratio. It may be why KMI’s stock is languishing.

DCF is Free Cash Flow (FCF) before growth capex. MLPs have long separated capex into (1) maintenance, required to maintain their existing infrastructure, and (2) growth, for new projects. FCF, a GAAP term, is indifferent to the two types of capex and deducts them both. DCF (not a GAAP term) treats them differently by excluding growth capex, and is always higher.

Unsurprisingly, KMI regularly promotes its 11% DCF yield, which is higher than its energy infrastructure peer group. However, FCF is the more familiar metric, and is lowered by the subtraction of growth capex. Because KMI spent over 70% of its $4.5BN DCF on new projects, the remaining $1.4BN in FCF results in just a 3.3% FCF yield. This is still higher than the energy sector and certainly better than utilities (which are often negative because of their ongoing capex requirements). But it doesn’t stand out versus other sectors, and probably causes analysts to overlook the high DCF yield.

As a corporation, KMI continues to promote a DCF valuation metric used by MLPs, Using the more common FCF yield, it isn’t compelling. However, DCF seems reasonable to us given their business model.

To see why, consider yourself owning an office building. After all cash expenses, including maintenance and setting aside money annually to replace HVAC and other equipment, it generates $1 million in cash, annually. In real estate this is called Funds From Operations (FFO). Because you’re already deducting the expenses required to keep the building operating, and it’s most likely appreciating in value, it’s reasonable to value it based on the $1million recurring cashflow. A cap rate of 5% means you’d require at least $20 million before agreeing to sell it.

Now suppose you decided to redirect $700K of your $1 million annual cashflow towards buying a second building that you also plan to rent out. You still own a $20 million asset, and reinvesting some of that annual cashflow in a new building doesn’t affect the value of what you already own.

In this example the $1million in FFO is analogous to KMI’s DCF. It’s why they believe their stock is undervalued, because 11% is a high DCF yield. Their FCF is so much lower because they’re investing most of their DCF in new assets that will generate a return.

GAAP FCF doesn’t differentiate between capex to maintain an asset and capex to acquire a new one, which is why pipeline companies don’t dwell much on FCF. Moreover, properly maintained pipeline assets generally appreciate. As climate activists slow new pipeline construction in some states, it simply raises the value of nearby infrastructure that can serve the same need.

Critics may believe that DCF doesn’t reflect all the necessary maintenance capex that’s really required, or that the underlying assets are depreciating in value even while properly maintained, although there’s little if any evidence to support either claim. So KMI remains misunderstood.

The dividend might offer a more compelling story. Yielding 4.7%, it’s below the 5.8% of the broad American Energy Independence Index. Because of history, investors are understandably cautious in buying for the yield. But today’s $0.80 annual payout is expected to jump to $1 next year and $1.25 in 2020. This 25% annual growth will push the yield to 7.4% in two years, assuming no upward adjustment in the stock price. A rising dividend might finally vanquish the unpleasant memories of prior cuts, and draw in new buyers.

In spite of its attractive valuation, MLP ETFs and mutual funds don’t own KMI, because it’s not an MLP, providing another good reason to seek broad energy infrastructure exposure that includes corporations.

We are long KMI and short AMLP.