Is BREIT Marked To Market?

How do you conservatively value illiquid assets in a fund that offers liquidity to existing investors and accepts money from new ones? That’s the unsolvable question inadequately answered by the $125BN Blackstone Real Estate Investment Trust (BREIT), which is why they were forced to suspend withdrawals.

Private equity funds typically raise money and invest it over time. Generally, a fund’s investors commit at around the same time and share the portfolio results pro-rata. If a seasoned fund allowed latecomers who were enticed by early investment results, it would be unfair to those who committed at the outset without that information. In such a case, conservative low valuations on existing investments would harm the early investors whose stake in those positions would be diluted on unfavorable terms. High valuations might dissuade later investors if they felt they were paying too much for the existing positions.

It’s why successful private equity managers run one fund after another. It allows them to keep raising capital while ensuring each class of investors is pari passu. With realizations driving liquidity for investors and the manager’s incentive fee, interim valuations don’t matter that much.

When it comes to illiquid assets such as real estate, a valuation range is more realistic than a single point. By allowing inflows and outflows, BREIT has sought to provide liquidity at odds with their underlying assets. Smooth monthly returns, the promise of “consistent, tax-advantaged distributions” and the Blackstone brand made BREIT attractive to institutions. Their published monthly returns go to two decimal places, suggesting a precision at odds with what they own. They’ve reported three down months out of 69. Such unerring profitability should draw skepticism.

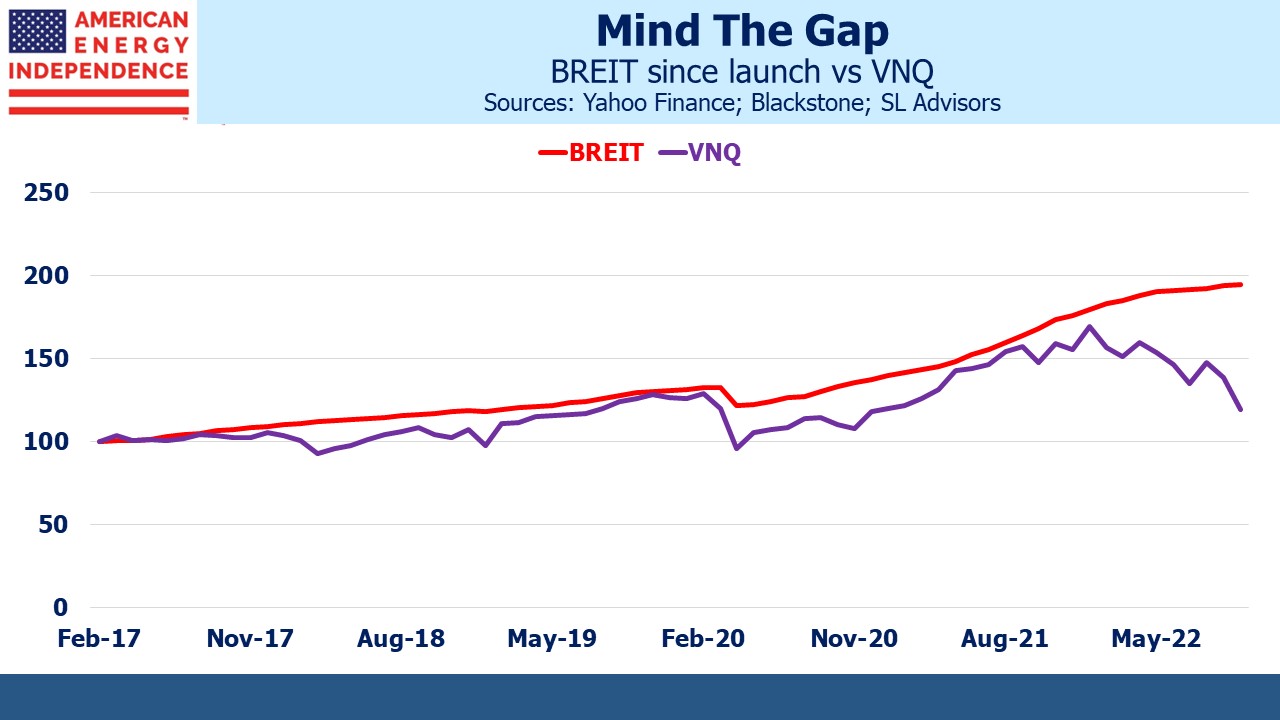

The fall in price of other publicly traded REITs has challenged the credibility of Blackstone’s valuation of the BREIT portfolio. The Vanguard Real Estate Index Fund (VNQ) was down 26% for the year through October. BREIT reports it is up 8.5% over the same period (they report with a lag). Some investors doubt that such a large fund could so nimbly avoid the markdowns that public market investors have endured. The biggest REITs in VNQ have seen their Price/Book ratio drop by over a quarter this year, suggesting book value for other funds will eventually be marked down.

BREIT addresses this, noting that they’ve sold $5BN of real estate this year “at a meaningful premium to carrying values.” They argue that because public real estate is only 8% of the market, private market values are more representative. Therefore, Blackstone regards today’s publicly traded real estate as being discounted to private market values rather than their own portfolio of private investments being overvalued.

Nonetheless, the BREIT investors who have exited recently and others blocked from doing so deem it attractive to redeem at an unchanged Price/Book.

Non-traded REITs, which are registered so as to have the widest possible set of buyers but unlisted to discourage analyst coverage, attract the ethically challenged as fund managers. Almost a decade ago we published Inland American Realty Runs Its Own Hotel California, concluding that disclosing how many ways you intend to fleece your investors can provide some defense when the SEC takes a close look. Non-traded REITs don’t perform regular appraisals, which has led their promoters to disingenuously extoll the consequent “absence of public market volatility.” For more, see Unlisted, Registered REITs; an Investment Designed for Brokers, and also chapter one of my 2015 book Wall Street Potholes.

BREIT shares some of the ignominious qualities of the maligned and shrunken non-traded REIT sector, although they prudently omit claims of low volatility or a high Sharpe Ratio that smooth monthly performance suggests.

Years ago as a hedge fund investor I ran into this problem with a convertible bond arbitrage fund (for the full story see The Hedge Fund Mirage Pp 107-111). If a fund’s bonds are priced by market makers at 101-102, they can be valued anywhere within that one-point range without the manager being open to accusations of misvaluation. If inflows are expected it can make sense to value at 102, pushing up the NAV at which new money comes in and helping performance.

Similarly, outflows might induce valuation at 101, benefiting remaining investors over those exiting. Since the manager must buy or sell bonds in response to flows, incurring transactions costs for the fund, this will always create winners and losers. Investors generally assume greater liquidity than really exists, and don’t consider transactions costs. Fund managers rarely educate them.

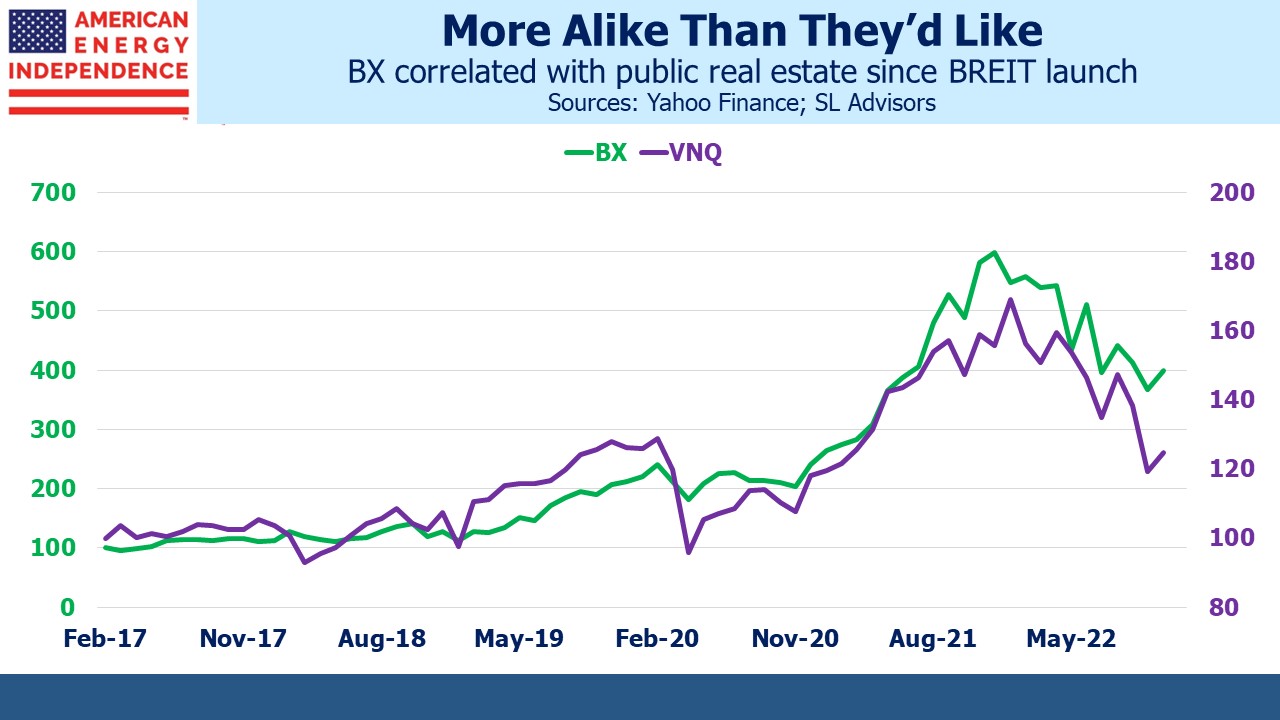

The less liquid the assets, the bigger the range of valuations. Real estate doesn’t belong in a fund that allows regular investor flows. BREIT’s NAV sweeps majestically higher, impervious to the carnage afflicting all markets other than energy. But investors in Blackstone’s stock (BX) see a closer relationship with public real estate values as measured by VNQ rather than the private valuations represented by BREIT. Blackstone created the appearance of public market liquidity for privately held assets and asserts valuations remain strong. Their bluff is being called.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment: