Infrastructure As An Inflation Hedge

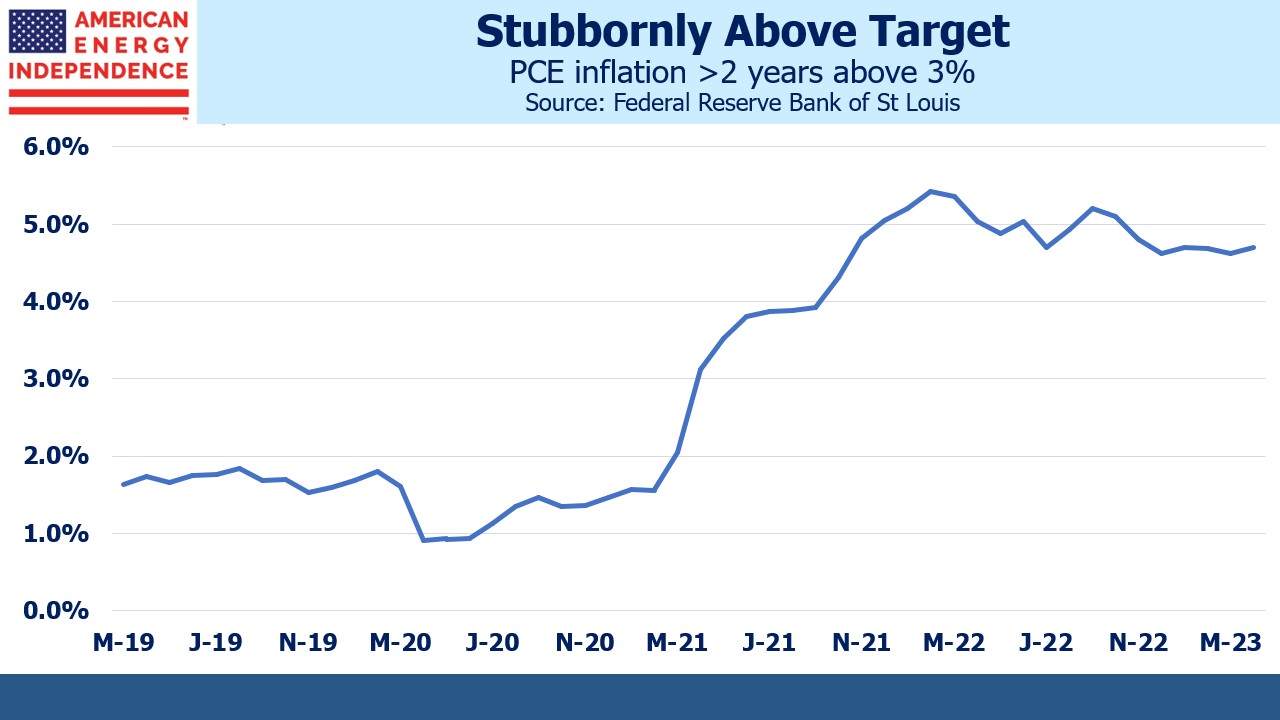

We’re getting used to 4-5% inflation. Using the Fed’s preferred measure, core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE), it’s been above 3% since April 2021. People are quietly mentioning the unmentionable – what if the Fed raises its inflation target?

The Economist recently published a briefing warning that “failure to quell it quickly will transform financial markets”. Whether the Fed suppresses the economy enough to get inflation back to 2% or not, it’s already too late for it to be quick.

Richard Clarida was vice chair at the Fed until he resigned in January 2022 amid controversy over well-timed personal stock trades just prior to a barrage of pandemic-related rescue programs. He returned to PIMCO. Clarida told the Economist the Fed, “… will eventually get the inflation rate it wants” adding, “It could be 2.8% or 2.9% when they start to consider rate cuts.”

Clarida joins a growing chorus of Wall Street strategists who are asking the same question. There’s nothing magic about 2%. It’s predictability that’s important, although the Economist goes on to argue that higher inflation is damaging precisely because it makes future inflation harder to forecast.

Don’t expect Fed chair Jay Powell to announce a revised interpretation of their twin mandate (full employment with stable prices). The last time they did that was following their 2020 Jackson Hole symposium. Powell expressed a tolerance for “…inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.” Thereafter, “transitory” became overused and then dropped from his lexicon.

We know this Fed focuses on whichever element of its twin mandate is farthest from target. They do not anticipate events, even though the tools of monetary policy take many months to have an impact. A jump in unemployment could see them pivot away from inflation.

As we’ve noted before, some investors are already considering how to respond (see 4% Inflation Is Our Least Bad Option). Aging populations in the rich world mean a shrinking labor force. Globalization, the big driver of disinflation for decades, is reversing as supply chains are modified to match national security needs. Apple is just one company planning to reduce its reliance on China by shifting iphone production to India.

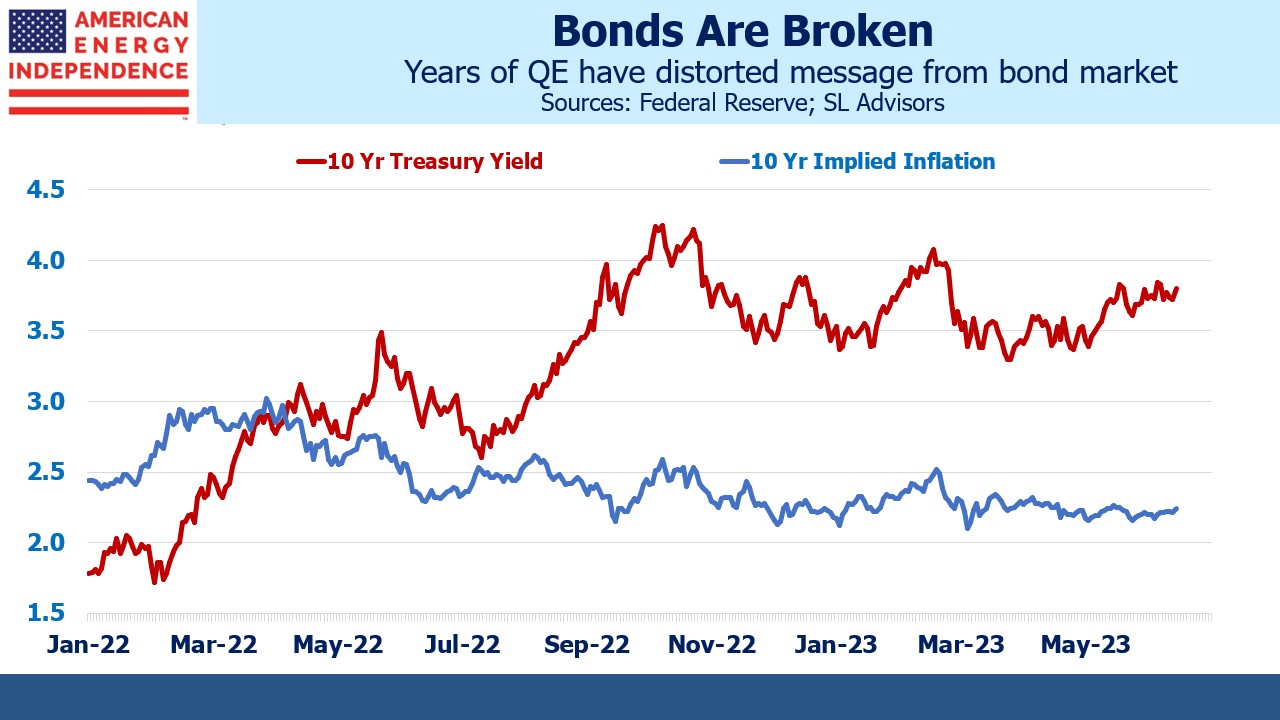

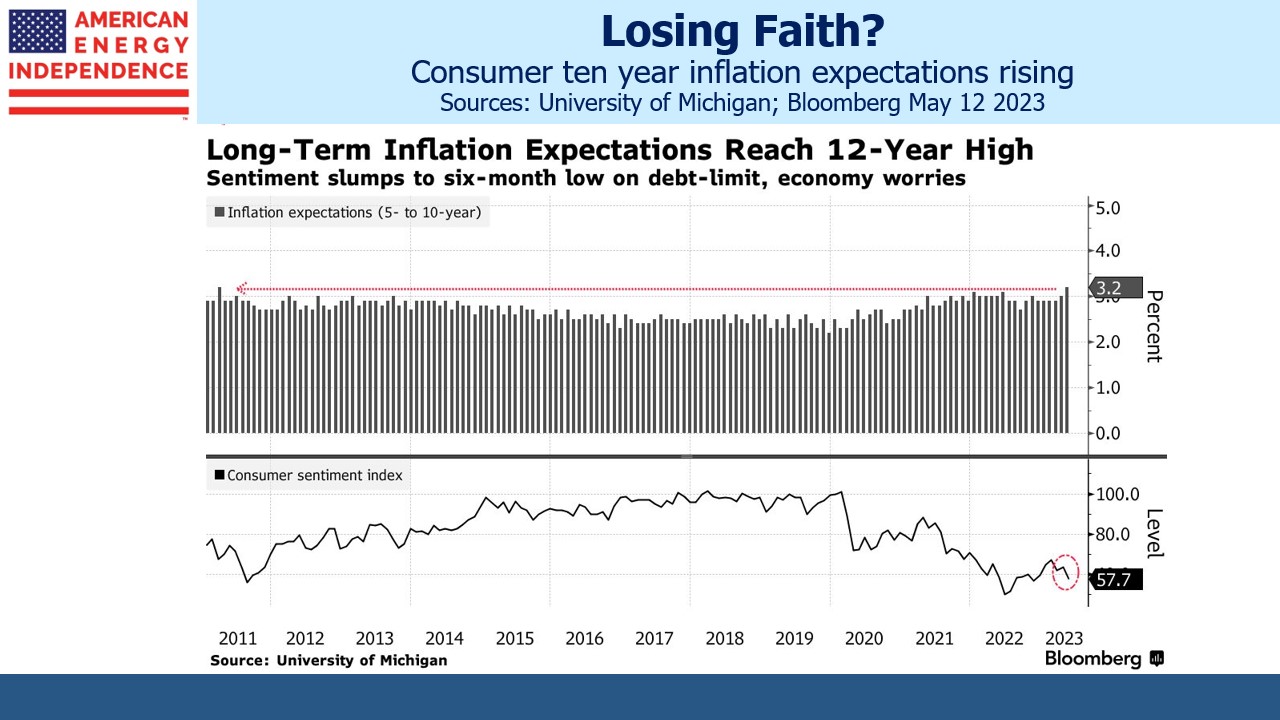

Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) are expensive, their prices as much distorted by the Fed’s QE purchases as conventional securities. Ten year TIPs at 1.5% are priced for ten-year inflation expectations of 2.2% when subtracted from regular ten year notes yielding 3.7%. This calculation has been below 2.3% all year. It’s a mistake to infer credibility in the Fed’s efforts. The University of Michigan survey shows ten-year inflation expectations have been rising all year, and now sit at a twelve year high of 3.2%, almost 1% above TIPs. This shows the bond market can’t be relied on as a measure of what investors think will happen.

Stocks are better than bonds in such an environment. Within the equity market, stocks with pricing power should offer protection. The Economist recommends physical assets including infrastructure, because they, “generate income streams, in the form of rents and usage charges, that can often be raised in line with inflation or may even be contractually linked to it.”

The Economist adds that such assets are hard to access, often “…dominated by private investment managers, who tend to focus on selling to big institutional investors.”

An important exception is midstream energy infrastructure, the regular topic of this blog. This sector might be the solution to any investor wanting a portfolio designed for a world where 4% is the new 2%.

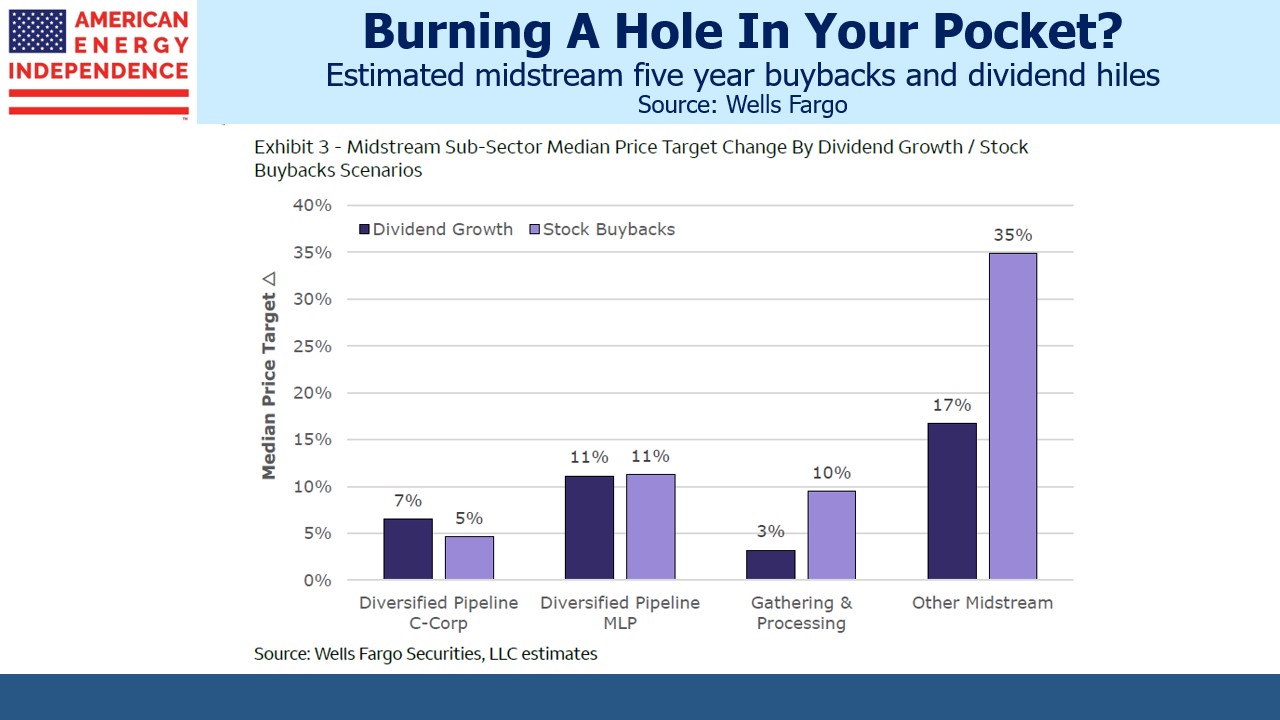

Right on cue, Wells Fargo just published Midstream: Capital Allocation Conundrum—What to Do with All That FCF? They see 10%+ price upside over the next five years from excess free cash flow deployed to either buybacks or dividends. Pipelines have pricing power, in that many tariffs increase automatically with inflation. These are scarce assets, thanks in part to climate extremists who have made new construction unappealing through persistent ruinous court challenges. Mountain Valley Pipeline will soon be finished, but the protracted timeline will serve as a warning that returns on growth capex can be uncertain. Hug a climate protester and drive them to their next protest.

Dividend yields are around 6%. The Wells Fargo analysis includes baseline 4.3% annual dividend growth and steady capex. The excess cash flow they project is worth around 2% pa. Adding the three together results in a 12.3% pa five year return. That’s not assuming any repricing as investors are drawn towards publicly traded infrastructure, even though returns like this would probably create their own momentum.

After reading The Economist’s Investors must prepare for sustained higher inflation, you’ll be relieved to turn to midstream energy infrastructure which just might be part of the solution.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment: