Governments And Their Energy Policies

Government regulations play a big role in energy markets. Although concern about climate change is part of the political discourse in every democracy, consumers and businesses aren’t going to reduce their emissions without tax credits, incentives and rules to modify behavior.

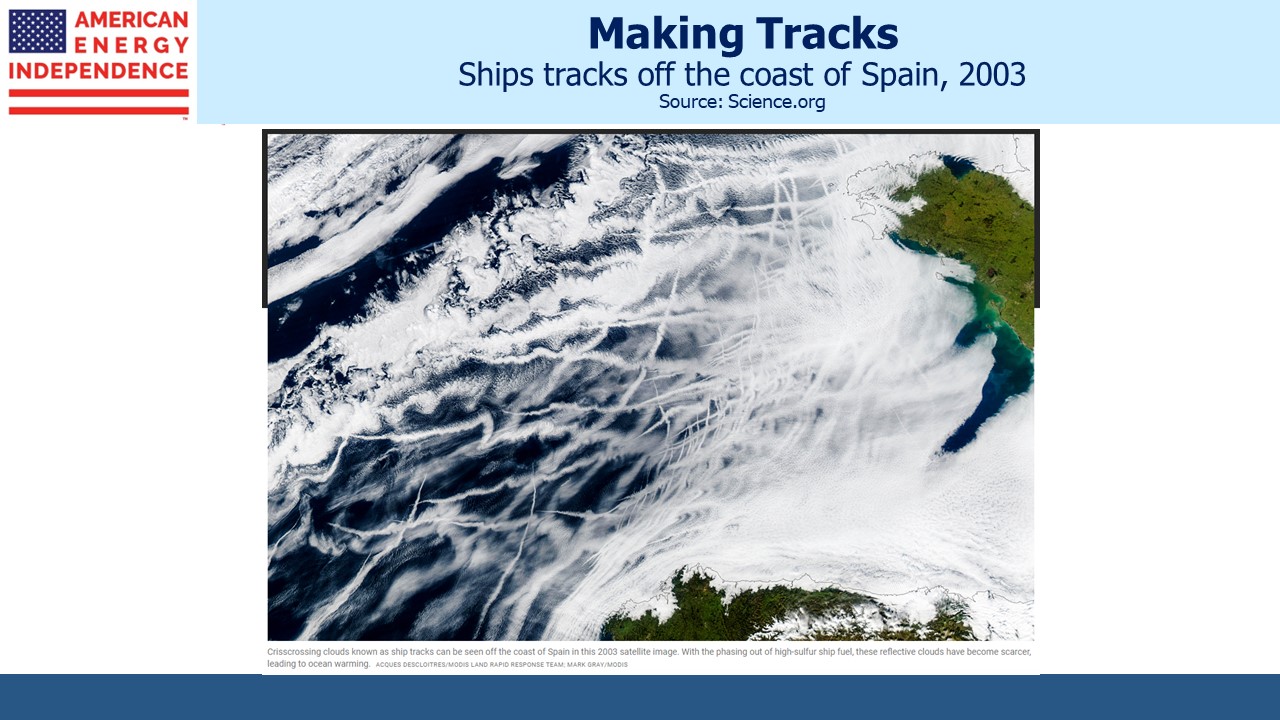

Sometimes policies can have unintended consequences. Take ships, which mostly use heavy, bunker fuel to provide power. In 2020 new rules written by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) came into effect sharply limiting the sulphur content of ships’ fuel to 0.5%, versus 3.5% previously. Airborne sulphur is a pollutant that can harm people with cardiovascular problems living near ports. Sulphur dioxide is a greenhouse gas. The new IMO regulations were intended to improve air quality and to reduce the maritime industry’s carbon footprint.

It sounded very sensible. But some scientists now think this is increasing global warming, and may even be responsible for the exceptionally warm Atlantic waters off the US east coast and on Ireland’s west coast.

“Ship tracks” are formed when ships move across the ocean. The sulphate particles ships emit seed clouds, creating a trail of reflective, cloud-like vapor behind them. These clouds reduce the amount of sunlight reaching the earth’s surface. The reduced sulphur content of bunker fuel required by the IMO means fewer ship tracks and has inadvertently allowed more sunlight through. In some areas it could have added as much as 50% of the warming impact of human-generated CO2.

If one day our descendants decide the planet is too hot, they may resort to geoengineering which could include seeding clouds on a vast scale to try and reflect more of the sun’s heat back out to space. The IMO regulations have unwittingly created a geoengineering experiment with the opposite effect. There have even been suggestions that ships should emit salt droplets as they move, to seed more ship tracks and undo the possible damage caused by their lower emissions.

Sometimes you just can’t make this stuff up.

Canada has been frustrated for years in its efforts to transport the heavy crude produced in Alberta to global markets. The Keystone XL was intended to be a solution until President Biden canceled it on his first day in office. Kinder Morgan wisely sold the TransMountain expansion (see Canada Looks North to Export its Oil) to the Canadian federal government in 2018. British Columbia didn’t want Albertan oil passing through its province, and the protracted political dispute eventually persuaded Kinder Morgan to give up on the project. Once the Canadian government took over vast cost increases took the project’s cost up by more than 4X. It is expected to go into service next year transporting crude from Alberta to the Westridge export terminal on British Columbia’s Pacific coast.

RBN Energy publishes a terrific blog for readers keen for a more technical explanation of markets, midstream logistics and the physics of this sector. In a fascinating post (unfortunately behind a paywall), RBN explains the challenges with getting the crude oil from Westridge into the wide blue ocean. The challenges are many. Ships must traverse a narrow channel to reach the Pacific. It’s constrained by depth and also height (because of two bridges). Bigger ships are more cost effective, but the 245 meter Aframax class is the largest ship allowed in Vancouver harbor. The biggest class of oil tanker, an Ultra Large Crude Carriers (ULCC), is 415 meters long and has over four times the carrying capacity of the Aframax.

Alberta’s heavy crude is, well, heavy. The 42 foot depth of the Burrard Inlet, through which the ships must pass, is less than the 49 foot draft of a fully laden Aframax, so they’ll have to operate at less than full capacity. Once outside the harbor some may even move their cargo of oil onto a bigger ship like a ULCC (called reverse lightering) for more cost-effective transport to their Asian buyers.

The complexity and cost of moving the world’s energy are largely hidden from view. Canada’s fractured politics have significantly boosted the cost of getting their oil exports to market.

Finally, Britain’s Conservative government seems to be quietly backing away from some of the more extreme commitments made in the past regarding emissions. The UK is ahead of many other countries, having phased out coal. Offshore windpower is at times its biggest source of electricity. The North Sea is a blustery place.

Britain has a system of carbon credits, and before Brexit their price tracked the EU equivalent quite closely. Now free of oversight from bureaucrats in Brussels, a weakening of regulations has caused UK carbon credits to drop to around half the EU price. This signals less urgency by British CO2 emitters to buy credits. UK PM Sunak may be quietly pursuing more pragmatic policies to try and boost GDP growth which has lagged peers for a decade (see UK government cuts cost of polluting in latest anti-green move). Nothing official has been said. But there’s a clear pattern around the world of voters pushing back once extreme green policies start to have an excessive economic impact.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment: