Bonds Are Getting More Interest

One of the most important questions for investors is whether interest rates will remain low. Persistent paltry yields still aren’t fully explained. Inflexible investment mandates affecting trillions of dollars are a partial explanation. For example, the equity risk premium favors stocks sufficiently that it’s possible to replace a ten-year government bond with as little as 20% of the money reallocated to stocks and 80% in cash (see Stocks Are Still A Better Bet Than Bonds).

The resulting barbell has a very high likelihood of delivering the same return or better than bonds, but conservative assumptions still fall short of a guaranteed outcome. Even though low yields should induce investors to allocate more to stocks, pension funds, central banks and others with rigid fixed income mandates continue to hold vast amounts of bonds with derisory yields.

Related to this is the continued drop in real yields. It’s a phenomenon that’s lasted several decades. The series below shows real yields on the average of U.S. government inflation-indexed bonds (TIPS) for over twenty years.

The decline in real yields led the FOMC to change how they implement monetary policy. A couple of weeks ago Federal Reserve Vice-Chairman Richard Clarida explained that the decline in real rates had also led FOMC members to steadily revise their forecast equilibrium policy rate lower. It’s fallen from 4.25% in 2012 to just 2.5% now. Even at that level, given the FOMC’s 2% inflation target it implies a neutral real policy rate of +0.5%, whereas long term TIPS yields are negative. That means that the FOMC may eventually revise their neutral policy rate lower still.

The reduced neutral short term rate is why the FOMC is willing to tolerate inflation modestly above 2%. Low rates offer less room to cut during a recession. The FOMC felt this risked inflation remaining below 2%, too close to damaging deflation for them to be comfortable.

Back in the 80s and 90s bond markets were interesting. Fed policy moved with economic cycles. Eurodollar futures could be traded. Since then, interest rates have offered many years of comparative boredom, with the 2008 financial crisis and Covid recession offering a brief respite from the slumber that enveloped fixed income.

We are likely entering a much more stimulating era. Bond markets are becoming interesting again and will command more attention from investors.

Excesses are building up. The government acknowledges few limits on spending (see Modern Monetary Theory Goes Mainstream). There are no fiscal hawks left in Washington. The Federal Reserve is partially monetizing the debt, by buying around $120BN per month. They have somehow convinced themselves that left unchecked bond yields would constrain economic activity, even though rates globally are low by any reasonable measure.

The FOMC is actively seeking higher inflation, insisting that when it appears it’ll be temporary and therefore insufficient to draw a policy response. They’ve also ruled out inflation in food and energy (always temporary and mean-reverting), housing (they always ignore this – see Why You Can’t Trust Reported Inflation Numbers), and many commodities (Covid-related logistical problems that will resolve themselves) as sources of concern.

Only rising wages will prompt them into action (see The Fed’s Narrowing Definition Of Inflation). The doctrine driving monetary policy is that it’s better to be late than early in tightening. Prior tightening cycles were often preceded by a concern that the Fed was late. Such fears may last longer than in the past, since this time tardiness is their intent.

Such circumstances create uncertainty about the outlook for interest rates, a key support under equity markets. They also make it more important for investors to consider inflation separately from interest rates, since the FOMC is relaxing the tether that historically connects them.

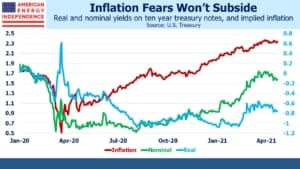

For much of the past five years nominal and real interest rates stayed close, reflecting stable inflation expectations. Covid and the resulting uber-stimulus have altered the relationship. Real interest rates have stayed negative – an implicit forecast of stealth monetization of debt.

In 2013 I published Bonds Are Not Forever: The Crisis Facing Fixed Income Investors. It forecast continued low interest rates and negative real yields as a relatively painless solution to excessive debt. Circumstances have continued in that direction, with Covid accelerating the trend. Currency debasement has a long history, as I recounted in the book. A client recently suggested I write an update.

The rise in ten-year treasury yields this year has prompted more investors to consider how they should respond to higher inflation expectations. The recent drop in nominal yields hasn’t been caused by moderating inflation fears – real yields have also dropped.

One could infer from this a growing realization by the market that the Fed won’t be quite as ready as in the past to protect purchasing power. Negative real yields should prompt greater urgency in the search for assets that will provide inflation protection. Investors need to look after themselves, since the Fed won’t.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.