Why The Fed’s Critics Will Become More Vocal

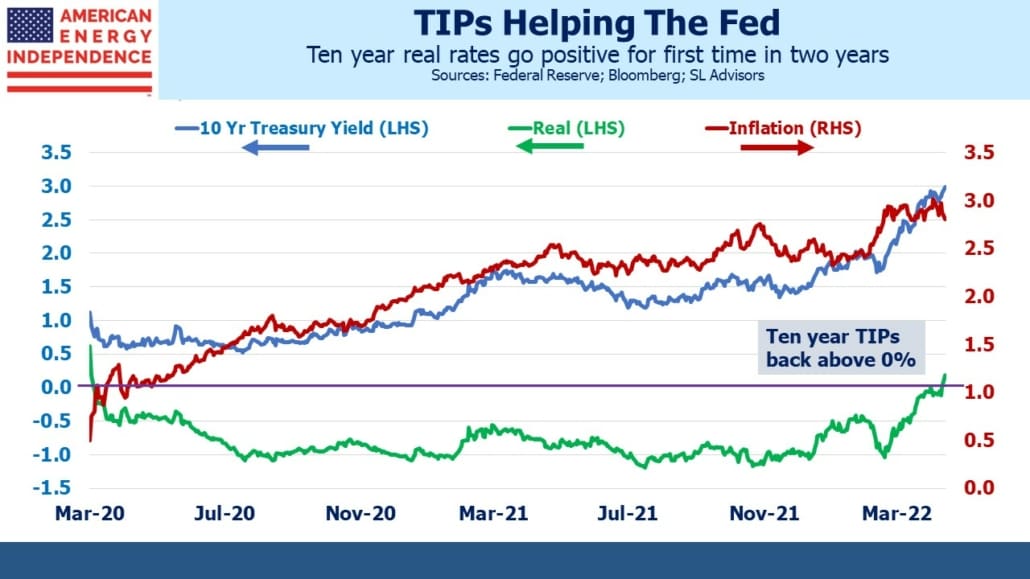

The ten year treasury yield touching 3% has drawn headlines, but the bigger story is that the increase in nominal yields has been driven by rising real yields. Ten year TIPs yield 0.18%, the first time they’ve been positive in over two years. Until recently, real yields had been declining irregularly for decades. $TNs of return-insensitive capital (central banks, sovereign wealth funds and others with inflexible investment mandates) is part of the reason.

The Fed needs tighter financial conditions in order to slow the economy. Higher real ten year yields help. Tighter monetary policy is most effective when it increases bond yields, because that’s where the economy and equity markets are more sensitive. Therefore, rising bond yields reduce the need for aggressive hikes in the Fed Funds rate.

Criticism of the Fed has been limited. Former Treasury secretary Larry Summers and former NY Fed president Bill Dudley are notable exceptions, and are well qualified to find fault publicly, as they have. Republicans have voiced unhappiness about elevated inflation, while Democrats seem to care more about the Fed’s approach to climate change. We may not like inflation, but since the cure is a weaker economy, we’ll like that a lot less.

Quantitative Easing (QE) was obviously maintained way too long, and the Fed is approaching its opposite, Quantitative Tightening (QT), cautiously. Much has been made of their decision to shrink the balance sheet, but they have over $1TN in treasury securities maturing within the next year. Letting these roll off won’t impact ten year yields. But they may sell Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS), which looks sensible because buying Fed buying of MBS has been supporting the strong housing market.

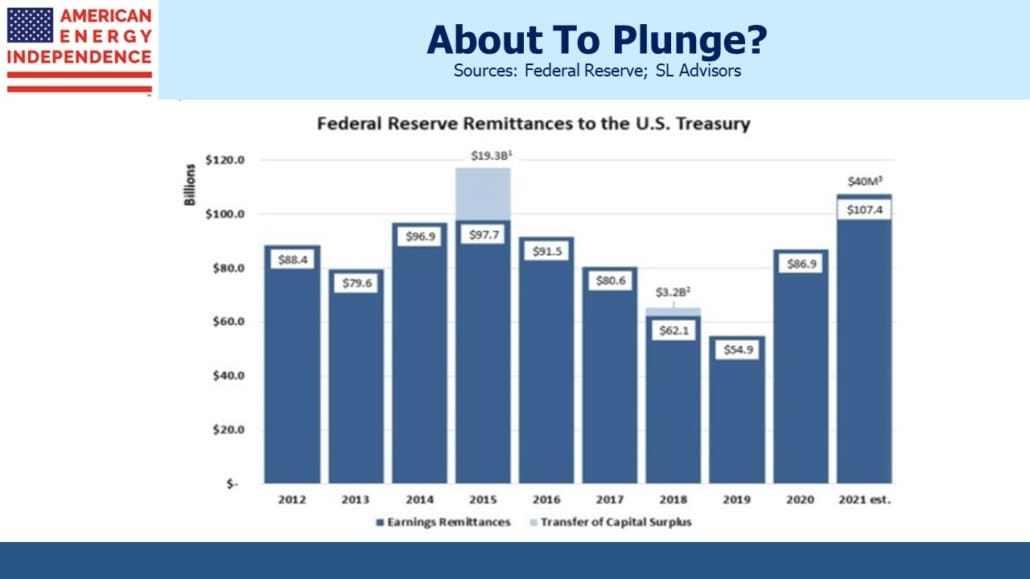

The Fed remits its operating surplus to the US Treasury every year. In recent years this has been swollen by positive net interest income from its $9TN balance sheet.

In its last fiscal year (ending September 2021) the Fed reported $122BN in interest income from securities. Its balance sheet averaged $8TN, so we can infer that the average interest rate on its portfolio is around 1.5%. After adjustments, net income of $107BN was remitted to the government.

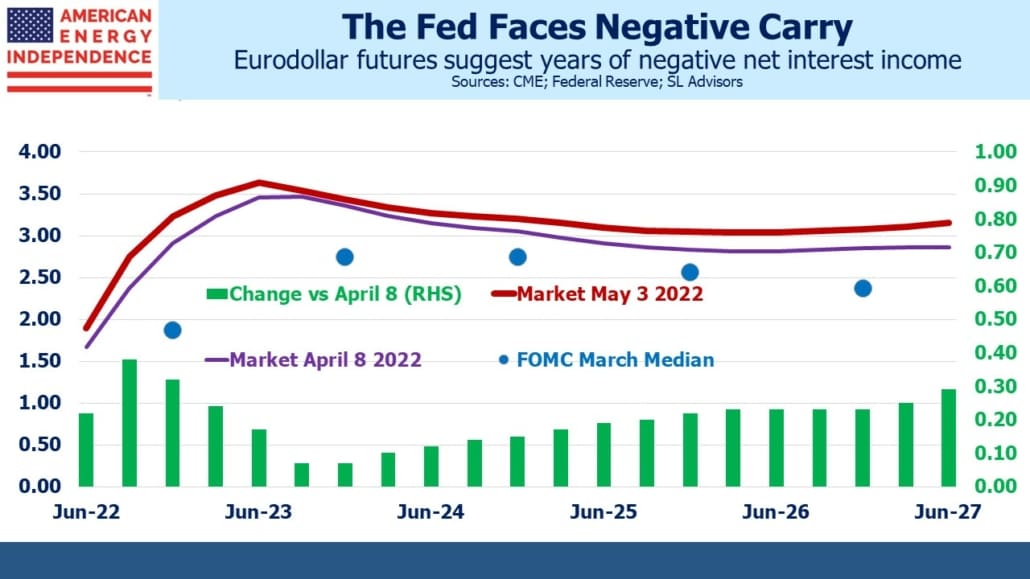

The Fed’s FY2021 interest expense was $6BN, but this is now going up. Assuming the $1TN in securities that will mature within a year yield 0%, the remainder of the Fed’s balance sheet yields just over 1.7%. Short term rates will be at that level by year’s end if not sooner. The 2022-23 fiscal year will see a steep drop in the Fed’s annual remittance to the Treasury. It could even flip to where the Fed has an operating loss.

Auctioning MBS would generate realized losses for the Fed. They have over $2.6TN in MBS with maturities of greater than ten years. Assuming a duration of ten and a 2% increase in yields from when they were bought, for every $100BN in MBS the Fed sells they’d realize a $20BN loss.

None of this will surprise policymakers, who we can assume took all this into consideration when they began the latest round of QE in 2020. They worried about their exit a decade ago, when wrestling with how to reduce their balance sheet following the 2008 Great Financial Crisis (GFC). Back then St. Louis Fed president James Bullard called it a “recipe for political problems.” They began tightening monetary policy in late 2015, and took almost four years to reach 2.4%. The Fed moved so slowly to unwind the GFC balance sheet that it wasn’t far below its 2016 $4.5TN peak before Covid led to a second round of QE. From 2015 to 2019 their remittances to the Treasury fell by almost half.

The Fed could argue that losses from QE are proof of its benefit. The higher rates that follow reflect QE’s success in arresting the economic decline that necessitated it. This is a sound economic argument, but not one that’s been tested yet. It’s the opposite of what deft currency intervention produces – a central bank that steps in to offset extreme moves in its currency is buying low/selling high – as long as it’s successful. Sometimes it isn’t. The 1992 collapse of Sterling against the Deutsche Mark overwhelmed the Bank of England, netting George Soros’s hedge fund an estimated $1BN profit on “Black Wednesday” (September 16, 1992).

QE is a buy high/sell low strategy. Because of the Fed’s error in maintaining overly accommodative policy for too long, they now must tighten more aggressively. It’ll take time, but the budgetary consequences of their poor decisions will reach the political classes in another year or so, in time for the 2024 presidential election. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that a 1% increase in rates above official projections increases the interest expense on Federal debt by $200BN. Their most recent forecast was for ten year treasury yields to average 1.6% through 2025.

Slower normalization of monetary policy and lethargic balance sheet reduction will allow higher inflation while smoothing the drop in Fed remittances to the Treasury. Such a debate won’t make it into the FOMC minutes, but will be on the minds of chair Jay Powell and his colleagues.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Please see important Legal Disclosures.