Why Oil Production May Disappoint

E&P companies routinely drill wells but hold off completing them until a later date. Completion includes creating a cement outer wall for the well to avoid leaks, and firing holes in the exterior in preparation for injection of fracking fluid under pressure. Typically wells can be drilled in sequence, as the drilling equipment is moved to the next site, but are completed in batches once a fracking crew is available. Drilled but Uncompleted wells (“DUCs”) are a form of production inventory, in that they represent future output once completed.

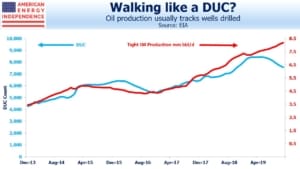

The Energy Information Administration collects data on DUCs, and it usually tracks production pretty closely. There’s an underlying assumption that a DUC will eventually be completed, but sometimes a drilled well is a dud, or completing it never becomes economically viable. Some believe that the EIA’s measure of DUCs is substantially overstated. This matters to future production, because fewer wells to be completed means less output, until more wells are drilled.

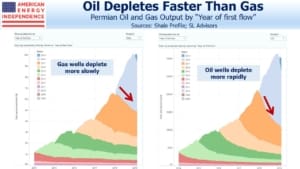

A characteristic of shale oil wells is that they deplete faster than natural gas. As crude production has increased in the U.S., this means that an ever greater number of new wells need to be drilled in order to compensate for depletion from an ever increasing number of current wells. Because this can’t happen indefinitely, production growth has to slow from it past torrid pace. We explored this in Drilling Down on Shale Depletion Rates.

The time from drilling to completion varies and doesn’t ultimately affect output, according to a study last year from the EIA (see Time between drilling and first production has little effect on oil well production). But it’s also true that the longer a well remains a DUC, the less likely it is to ever be productive.

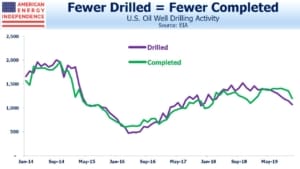

Currently, we’re completing around 1,200 wells per month. The EIA study referenced above estimated 3-4 months on average between drilling and completion – this was based only on North Dakota, so subsequent inferences rely on that single region to represent the country. But assuming the 3-4 months applies more broadly, that implies 3,600 to 4,800 DUCs in rolling inventory.

In recent months, DUCs have fallen noticeably although tight oil production has continued to grow. At around 7,500, DUCs are only modestly above our assumed rolling inventory. Because production has begun to diverge from DUCs, it suggests either drilling activity must pick up sharply to restore DUCs to output, or output itself will fall.

This doesn’t allow for any overestimate of DUCs by the EIA. Criticism from industry executives include comments such as, “My sense is the EIA DUC number implies more production capacity than actually exists and leads to downward revisions of supply estimates, which we have seen in the last six months.” Another added, “The EIA has no clue on their estimated number of DUCs, in my opinion.” Sadly, the executives are unnamed in last September’s piece from S&P Global Platts (see US producers criticize EIA estimates of DUCs, clouding production outlook).

Others seem to agree though. Raymond James estimates that the EIA is overstating DUCs by 2,000 wells. Spears & Associates believe the EIA may be overestimating DUCs by 3,000. In the last six months of 2019, completed wells exceeded drilled by 140 per month on average. If Raymond James and Spears & Associates are right about the EIA’s overstatement, then we’re already out of true DUC inventory.

The EIA is forecasting 13.3 Million Barrels per Day (MMB/D) of U.S. crude oil production this year, up from 12.2 MMB/D. The falling DUCs and possible overcounting create downside risk to this forecast, and upside potential for oil prices.