Why Natural Gas Affects Prices At The Pump

The other day a White House spokesman offered familiar criticism of oil companies for not reducing gasoline prices to match the recent drop in crude. It’s easy to manipulate charts to make a point, and the example used in the press briefing does that.

Gasoline prices have fallen recently, but is their relationship with crude oil changing?

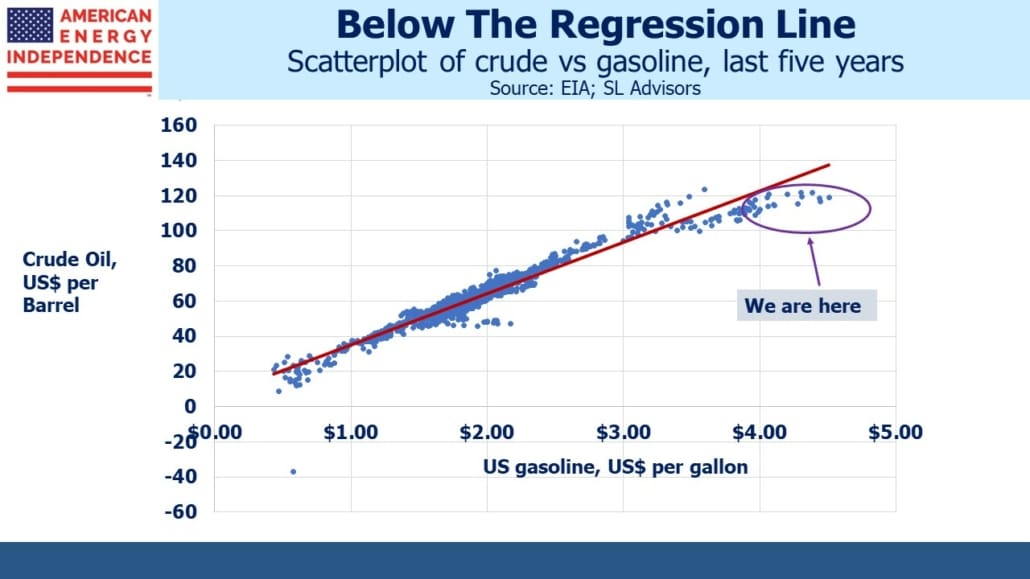

It turns out that a scatterplot of crude vs gasoline over the past five years can be interpreted to support the White House claim that prices at the pump haven’t dropped as much as they should. Today’s gasoline prices are notably off the linear regression line over the past five years. It’s absurd to blame this on oil companies – it is a competitive market and there have been no serious charges of collusion. So what has changed?

One area is net trade. The US is divided into Petroleum Administration for Defense Districts (PADDs) which date back to WWII. Data on oil and refined products is mapped into these regions by the Energy Information Administration (EIA). The US generally imports gasoline into PADD One (east coast) because that’s where the ports are. It is used within the region and elsewhere across the country. We export from PADD Three (the Gulf coast) because that’s where many of our refineries are located.

We produce over 9 million barrels a day of gasoline. US refineries usually operate at >90% of capacity, and that is the case today. They’re pumping out as much as they can.

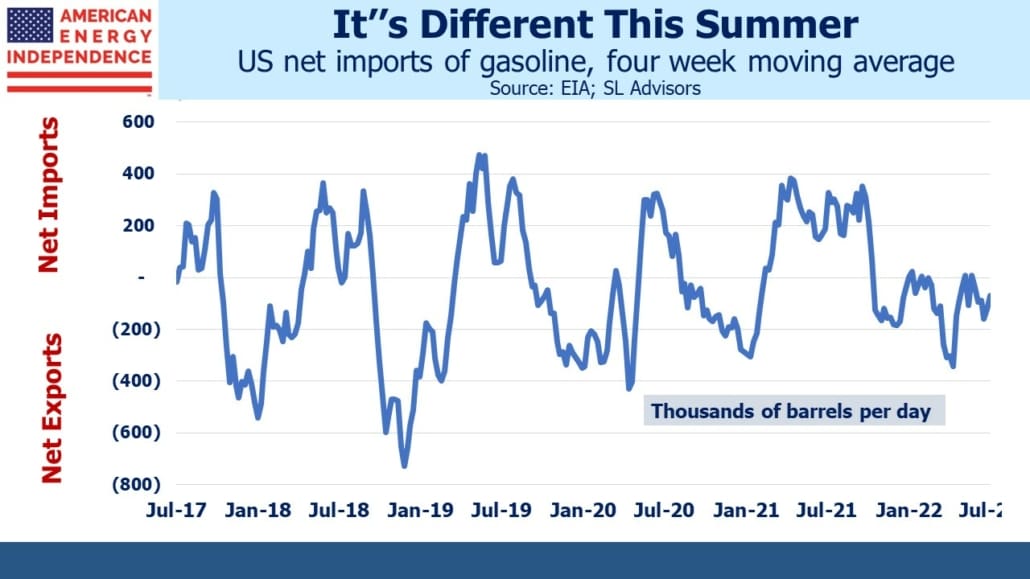

Trade flows tend to be seasonal – in the past five years we’ve been a net importer and exporter of refined products. We tend to be a net importer during the summer when domestic demand is highest. However, this summer we’re a small net exporter. Less gasoline is coming into the US than normal.

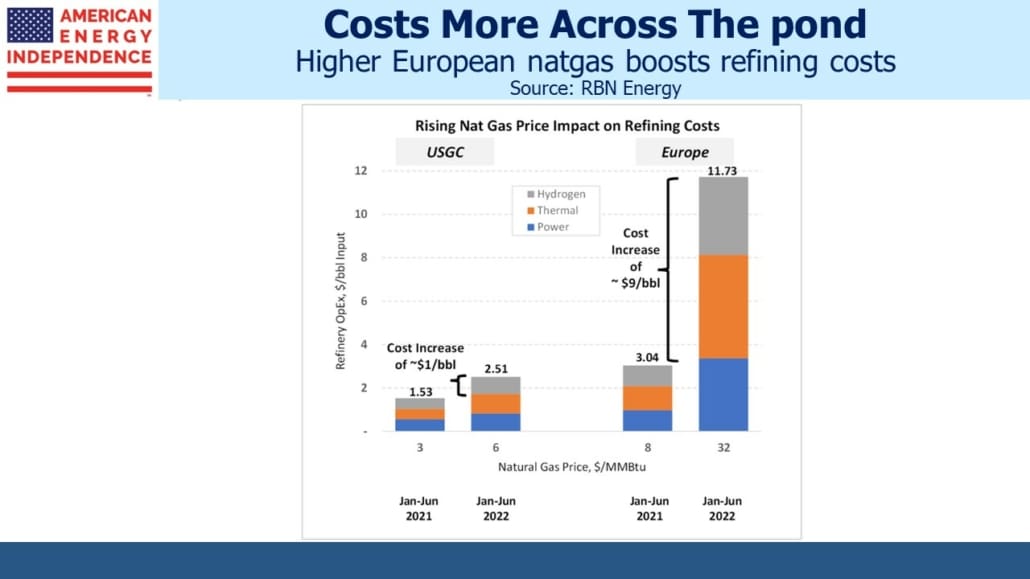

To understand why this is the case it helps to look at refinery inputs. Converting crude oil into gasoline is an energy-intensive process. Heating and vaporizing are critical steps in refining. Although some refineries produce fuel gas as an output, which then powers their processes, they also use a lot of electricity which is often generated by burning natural gas.

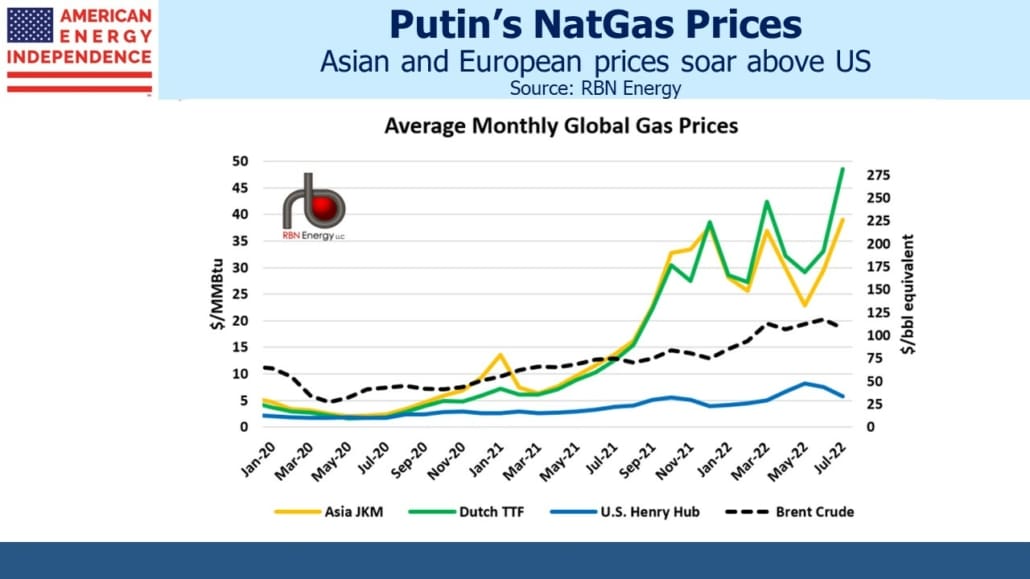

The global market for natural gas allows for much bigger regional variations than does crude oil, which is relatively easy to transport. Natural gas moves through pipelines or, when compressed into Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG), by specialized ship. The facilities required both to ship LNG and receive it along with their cost mean transportation expenses figure much more prominently than for crude. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused big spikes in LNG prices in Europe and Asia. In energy equivalent terms, US natural gas costs around a quarter as much as a barrel of crude whereas Europe and Asian prices are around two times as much – 8X the US equivalent price.

Natural gas as an input to US refining costs up to around $2.50 per barrel of crude, so it’s not a significant cost. The global pricing described above shows that in Europe it’s substantially more – perhaps 8X as much. Refineries in Europe and elsewhere that might normally export gasoline to the US east coast are finding they’re no longer competitive – hence the typical surge in net imports that comes with the summer driving season is absent.

For more detail on why prices at the pump high remain high, check out RBN Energy’s recent blog post Bring Me Some Natural Gas – A Key Driver Behind Today’s High Refining Margins.

The president is blaming greedy oil companies, a simplistic message not supported by any evidence. He’s trying to deflect blame for gasoline prices heading into the midterms. Perhaps the solution is really too complicated – this blog post won’t easily fit into a soundbite.

But it does show how interconnected different elements of the energy complex are. In the US we’re fortunate to have relatively cheap natural gas, despite the Administration’s vilification of anything fossil fuel related. Russia’s invasion is partly to blame, although the European natural gas prices are the cause along with higher crude.

EQT Corporation, a natural gas producer, released a survey showing that nearly 70% of voters support increasing natural gas production. The support was bipartisan. EQT is hardly an unbiased observer, but politicians are learning that we want our energy to be reliable, not intermittent, and not unreasonably expensive. The White House promises “good-paying jobs and energy security.” So far there’s not an example to emulate. The truth is that transitioning to a low carbon economy will be hugely expensive and disruptive. Because it’s not sold honestly, support is thin. Inflation in food and energy is the more immediate problem facing most people, and today’s climate policies are partly to blame. Natural gas is vital to today’s energy supply and will be crucial to any thoughtful path forward.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Please see important Legal Disclosures.