Why Aren’t Renewables Stocks Soaring?

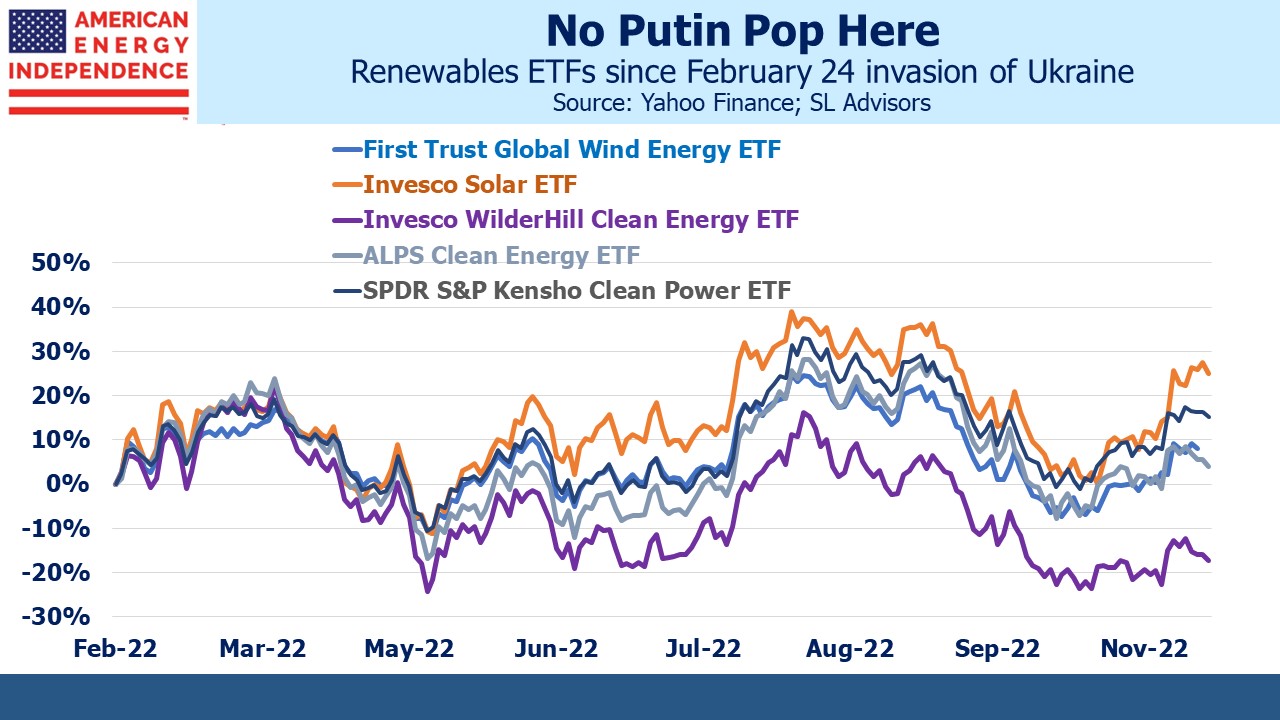

2022 should have been a great year for renewables. The prices of fossil fuels, which they are supposed to replace, have jumped. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has heightened the importance of energy security, which solar panels and windmills offer because most countries can find places to build them. And global Green House Gas emissions (GHGs) have rebounded following the dip caused by the pandemic. So why aren’t renewables stocks riding high?

One reason could be that some of them had benefited from the long rally in tech stocks. Investors in both sectors are typically relying on high growth rates which means years of waiting for a reasonable free cash flow yield. Rising interest rates put a higher discount rate on those delayed future earnings.

A more likely answer is that investors are becoming more realistic about the profitability of renewables. Germany’s north coast is windy, but they and others scrambling to replace Russian natural gas did not bid up the price of windmills. Instead, they hoovered up every available Floating Storage and Regasification Unit (FSRU) on the planet. The onshore pier, pipelines and electricity lines for the first one were completed last week in a brief 194 days in Wilhelmshaven on the North Sea. They’re also planning to build onshore import terminals for LNG, which have greater capacity than FSRUs.

European LNG prices famously reached ten times the US price earlier in the summer before dropping back to around 5X now. European storage is full in preparation for winter. Dozens of LNG tankers are idling offshore waiting for better prices before they unload their cargoes. Many analysts expect it’ll be harder to replenish stocks for next winter, since Russian gas was flowing west through Nord Stream 1 for the first half of this year.

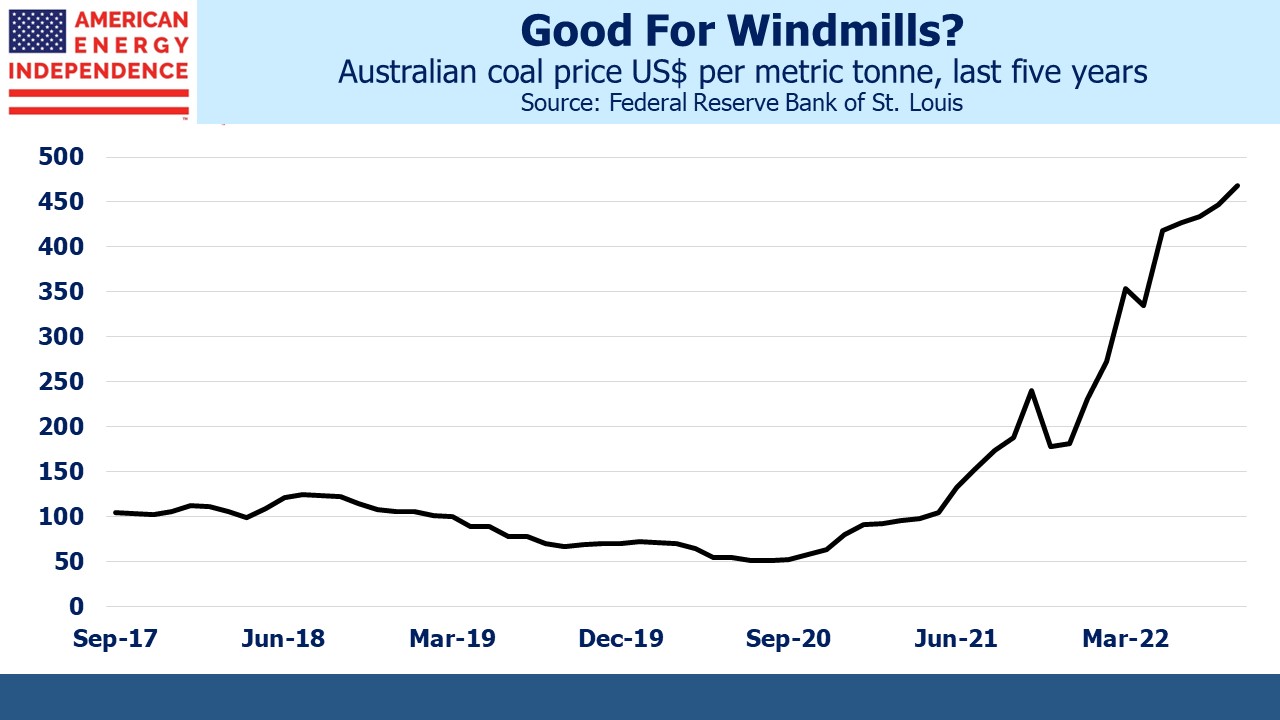

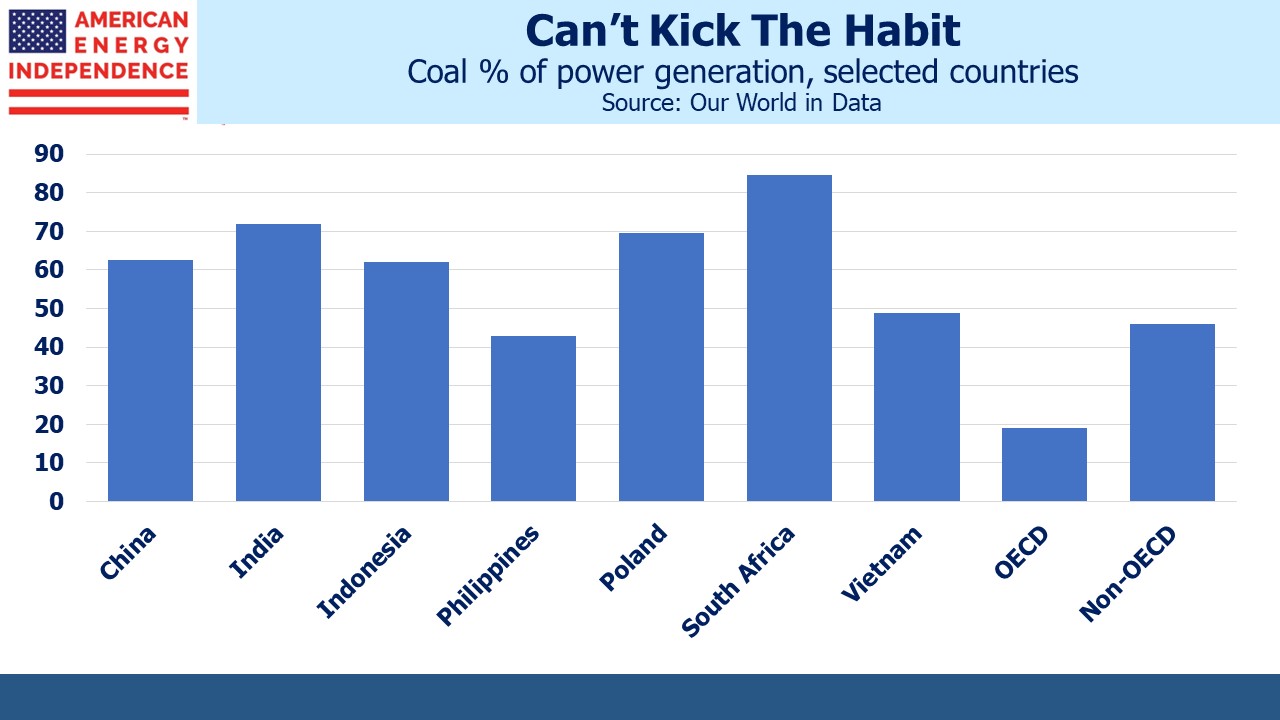

Coal prices have soared as developing countries have been deterred from competing with Europe’s new appetite for LNG. Among non-OECD (ie developing) countries coal provides 46% of their power, versus only 19% in the rich world. And developing countries are where energy demand is growing.

China burns half the world’s coal and relies on it for 63% of their electricity. They’ve even justified new coal plants as necessary for energy security (what’s Chinese for chutzpah?). Egypt is making government buildings and shopping malls turn their air conditioning up to 77° F, thereby reducing domestic demand for natural gas so they can export more.

Coal and gas together provide 59% of the world’s electricity, and both are much more expensive than a year ago. It’s as if the world had agreed on carbon taxes to improve the economics of renewables. There are numerous articles stating that solar and wind are cheaper than reliable energy, most of which pre-date the run-up in coal and gas. Renewables stocks should be soaring.

But they’re not. Danish wind turbine manufacturer Vestas expects a profit margin this year of minus 5% and recently reported a bigger 3Q loss than expected. They are optimistic that they can boost prices over the long run.

The CEO of Siemens Energy reminded viewers on CNBC that, “renewables like wind roughly, roughly, need 10 times the material [compared to] what conventional technologies need.” Current fiscal year EBITDA is down 42% and the company isn’t planning to pay a dividend.

UK solar operator Toucan Energy has gone bankrupt, with debts including £655 million ($779 million) to Thurrock Council, the local government where it operates. Neighboring London averages 1,481 hours of sunshine a year, which is 17% (Tampa, FL is 33%). 48% of UK electricity comes from natural gas. Although solar is 7%, UK solar farms can expect 83% or more downtime. Combined cycle natural gas power plants are typically down 5% of the time for maintenance. That’s why Toucan borrowed money from a local government rather than return-oriented investors.

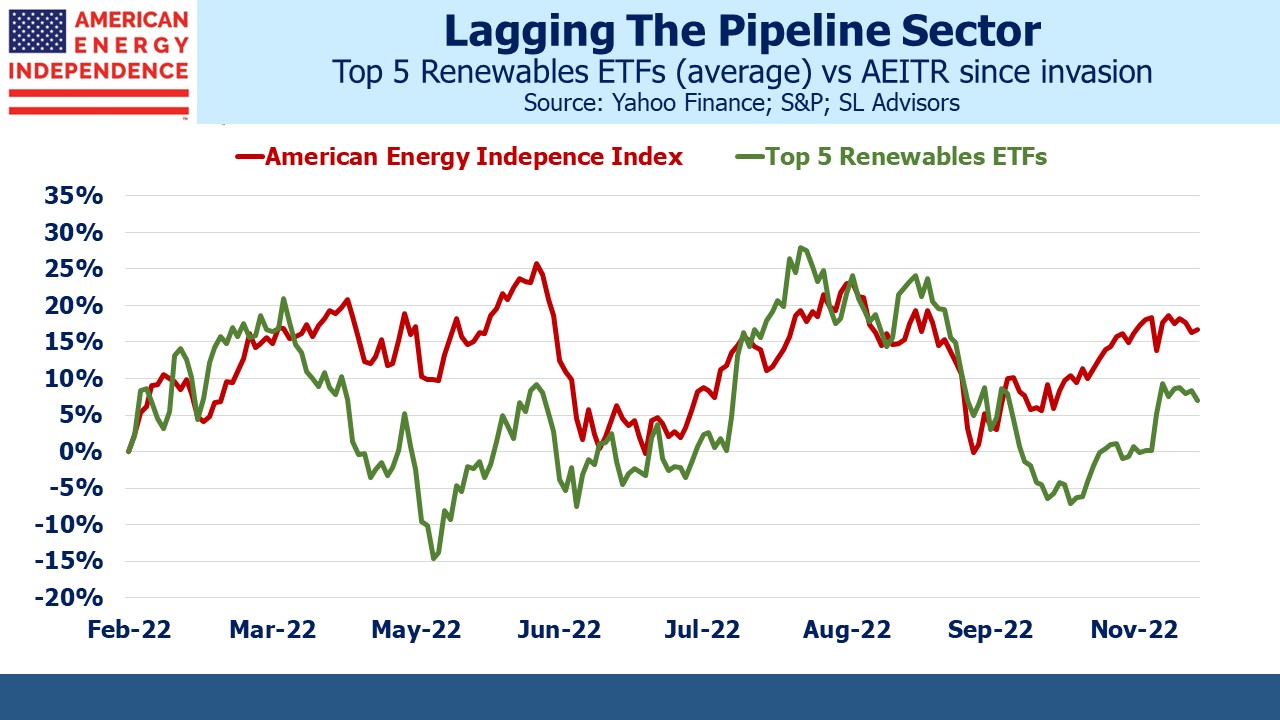

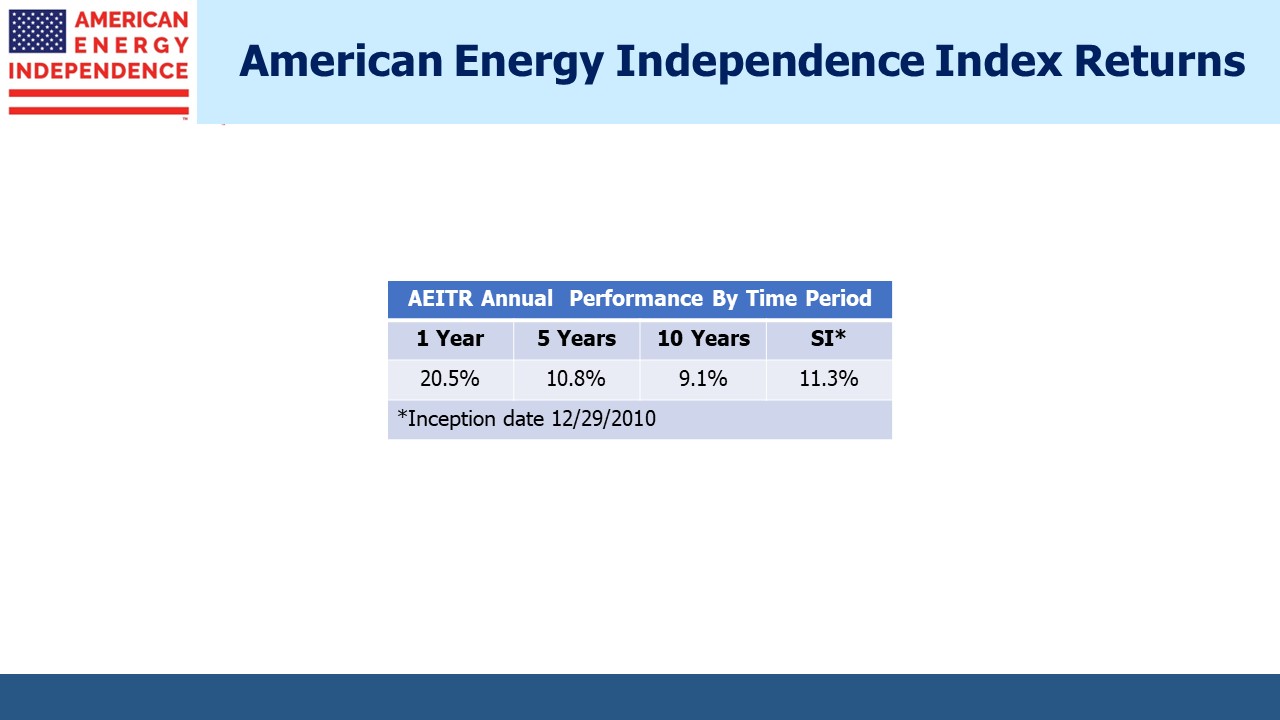

The five biggest renewables ETFs are beating the S&P500 but lagging the American Energy Independence Index (AEITR). The global economy is rebounding from Covid, apart from China. Relying on foreign countries for energy is suddenly riskier. Fossil-fuel inputs for almost 60% of the world’s electricity have jumped in price. All these factors should have made renewables a hot sector.

Instead, a weary realism has cooled belief in a rapid energy transition. Developing countries are looking for very large payments from the rich world to help them invest in cleaner energies. This challenges the claims of those who argue that solar and wind are already the cheapest way to generate electricity.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts 0.5% annual production growth in natural gas through 2030 in their Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS). This is the most plausible one because it doesn’t assume every government’s climate pledges will be fulfilled. In their 2022 World Energy Outlook the IEA expects unconventional gas production (ie shale, overwhelmingly US) to grow at 2% annually. They estimate 750 million people don’t have access to electricity, and 2.4 billion don’t have access to clean cooking (meaning they cook using fuelwood, charcoal, tree leaves, crop residues or animal dung). Getting these families onto natural gas would improve their lives and leave the planet better off as well.