What the Midterms Mean for Stocks

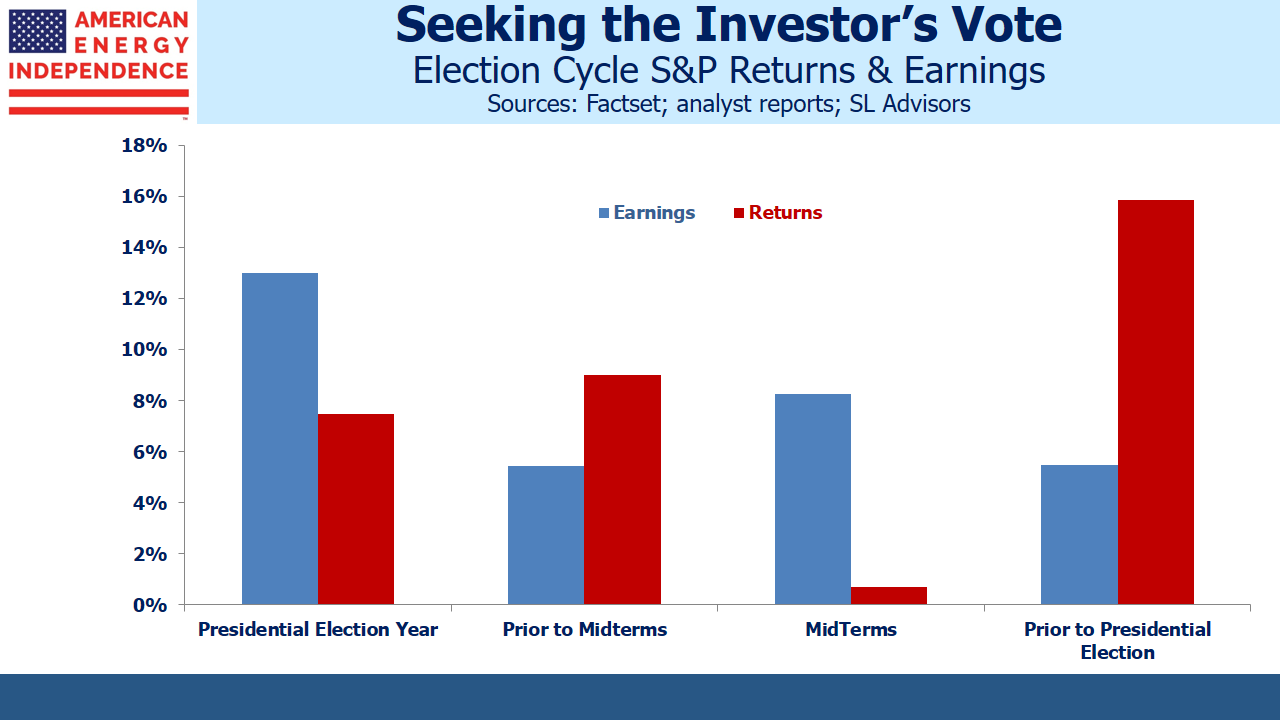

Equity returns are historically strongest in the year following the midterms. Conspiracy theorists will judge that politicians in office focus on market-friendly moves that aren’t limited to government spending in order to stay in power. Whatever the reason, the effect is quite remarkable. Since 1960, the S&P500 has risen by 15.9% on average in the third year of a Presidential cycle, almost twice the 8% average across all years.

When equity returns in the year following midterms have been poor, the White House has often changed hands. In 2015 stocks were flat and Trump’s victory followed. Eight years earlier, modest losses in 2007 provided Obama with his opening, and the 2008 financial crisis confirmed the pattern.

Many people feel that a divided government is preferable since it requires both parties to compromise in order to achieve anything. With the House of Representatives shifting to Democrat control, legislation will require support from both parties. However, the numbers don’t support this, with such returns in the year following midterms 1% lower if one of the two houses of Congress is controlled by the party not in the White House.

So history suggests 2019 should be a good year for stocks.

But much about the Trump presidency is different. Looking at S&P500 earnings by year presents a different picture. Earnings growth in a midterm year is 8.3%, approximately the average. Earnings tend to be strongest in Presidential election years. That’s partly what drives good returns following midterms, because investors look ahead to stronger profits the following year.

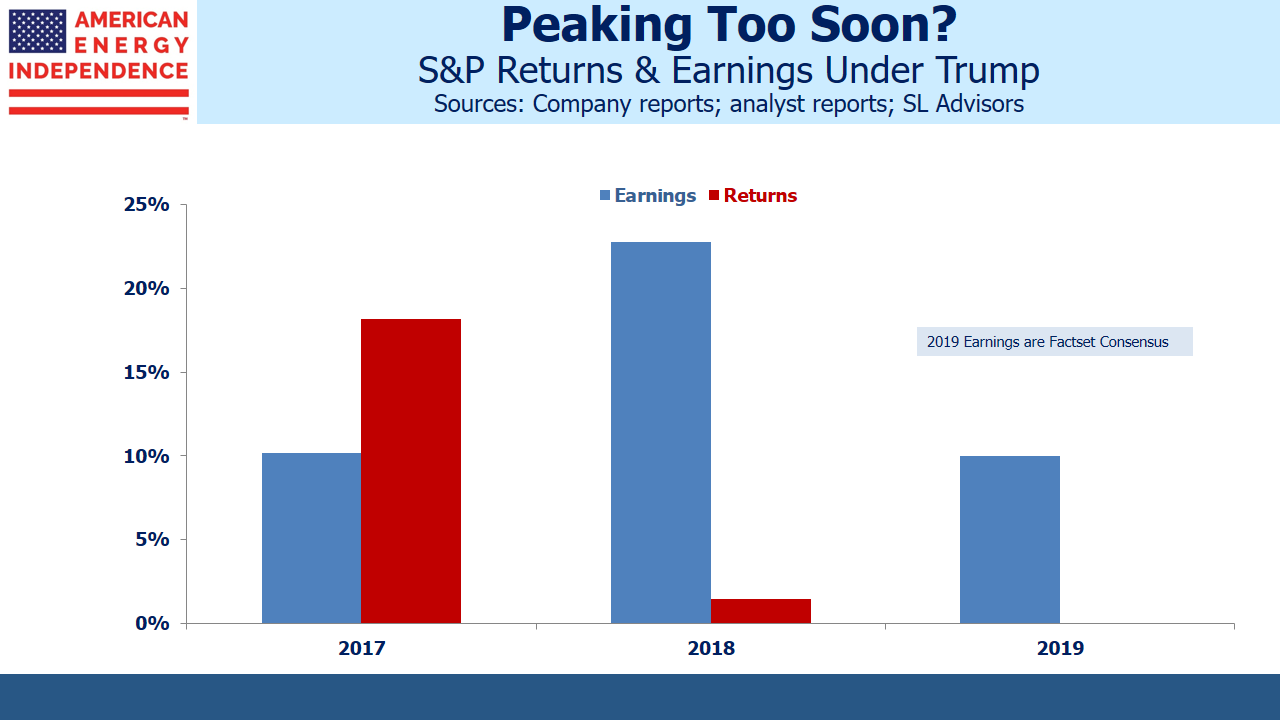

2018 S&P earnings are coming in at +22%, fueled by the cut in corporate taxes. That’s likely to be the strongest profits year of the four year cycle, and it’s come two years ahead of what typically happens.

So it’s possible the election cycle effect may have already peaked; last year’s 18% rise in the S&P500 was looking ahead to this year’s jump in earnings. The new administration completed tax reform following its first full year in office.

Factset is forecasting 10% earnings growth for 2019 – still higher than the 50+ year average albeit down sharply from this year.

In addition to the votes for elective office, many states included ballot questions for voters to consider.

Colorado included a proposal (Proposition 112) that would mandate a 2,500 foot setback for oil and gas development (including gathering & processing plants and pipelines) from “vulnerable” areas (residential neighborhoods, schools, parks, sports fields, general public open space, lakes, rivers, creeks, intermittent streams or any vulnerable area). Analysis showed that it would essentially ban oil & gas development on non-federal lands. It was a keenly contested issue, with one side claiming that energy extraction is endangering air quality while the other noted the jobs at risk from such a move.

Voters rejected it 57 to 43, which is a relief for Colorado’s oil and gas industry. Strikingly, Weld County, home to most of Colorado’s drilling, voted against 112 by a resounding 75/25. If the people closest to it are so strongly in favor of its continuation, it’s not clear why a statewide ballot was the right approach.

Proposition 112 was in any case likely unconstitutional, since leaseholders losing their property (i.e. their foregone right to drill for oil and gas in affected areas) would have sued the government for compensation. It illustrates why direct democracy is such a clumsy instrument, since “yes/no” public questions aren’t easily translated into coherent legislation. Politicians in the state had previously failed to act, which created enough public support to get the question on the ballot.

Even though Proposition 112 lost, it reflects the ambivalence of many regions over the development of America’s hydrocarbon reserves. The energy sector spent money on commercials highlighting the threat to the local economy, given 112’s stifling provisions. Colorado’s legislature is now likely to take up the issue and pass legislation intended to address the concerns of the proposals supporters. It means existing energy infrastructure already in service has a little more value, given increasing challenges to development.