Using More Energy, Everywhere

Last week the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) released their 2021 Annual Energy Outlook (AEO). It is produced by their Bipartisan Policy Center, and presidential elections aren’t supposed to affect their work. It isn’t a policy document but is intended to make forecasts based on current policies and known technology.

Past AEOs are taken down from their website, which is a pity because it can be fun comparing current forecasts with prior ones. Fortunately, we save it every year, and the comparisons are interesting.

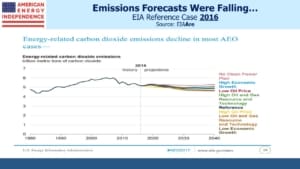

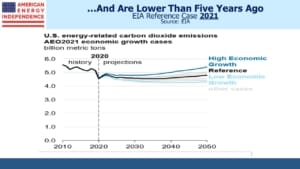

Our initial thought in watching the webinar that launched their new release was that they see a very different energy future than the new Administration, one that still relies primarily on fossil fuels. Joe Biden ran on a platform of getting the U.S. to net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. The AEO projects a modest drop over the next decade before growth resumes. Energy-related CO2 emissions are projected to remain below 5 gigatons by 2050, roughly unchanged over the next three decades but clearly not zero. Nonetheless, it’s a more optimistic than the 2016 AEO. Since then, switching from coal to natural gas for power generation and the Covid-recession have brought emissions down from above 5 gigatons back then. Changed policies and new technologies will be needed to alter that projection.

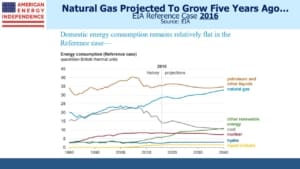

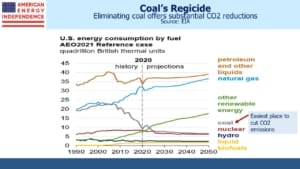

The 2021 AEO projects faster growth in renewables than five years ago, but oil and gas consumption still dominate. In fact, growth in natural gas consumption is expected to track renewables closely, with both gaining market share. Coal has seen a big downward revision since 2016 but will continue to provide more energy than nuclear. If we can’t flip that around over three decades, it will represent a significant missed opportunity.

One controversial element of the 2021 AEO concerns consumption of petroleum and other liquids. By contrast with AEO 2016, this is now expected to grow, in apparent defiance of everything the Administration and many others have to say. The explanation is greater industrial use of liquified petroleum gas (LPG) which is mostly propane and butane. The U.S. produces 40% of the world’s Natural Gas Liquids (NGLs), almost three times the next biggest (Saudi Arabia, at 14%). NGLs, which include propane and butane and are usually separated from “wet” gas, are one of the Shale Revolution’s big successes. In recent years, increasing domestic production has spurred investment in domestic petrochemical facilities and driven greater exports.

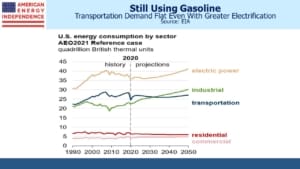

But even gasoline consumption is expected to remain close to current levels over the next thirty years. That it won’t grow reflects increased electric vehicle penetration as well as continuing efficiencies in traditional internal combustion engines. GM recently announced plans to only sell zero-emission cars and trucks by 2035. The incongruity between AEO 2021 and GM’s investment plans lies in policy expectations. GM is preparing for a world of government-imposed constraints on gas-powered automobiles, whereas the AEO 2021 Reference Case assumes unchanged policies. In 30 years we can look back and see which one of these was way off

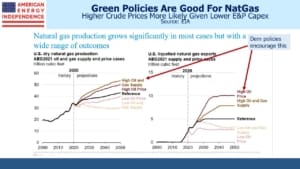

The other big change is in natural gas exports. In 2016 the EIA expected the U.S. to be a net importer of natural gas, while five years later that has reversed. An interesting chart which is more relevant today shows high oil prices stimulating increased natural gas production, because of substitution. The continued decline in capex for new oil production across the industry makes supply-constrained higher oil prices more likely than in the past. Previous AEOs have long considered this link, but it now is a higher probability. Democrat policies are designed to promote higher energy prices, an unintended benefit for energy investors.

The 2021 Annual Energy Outlook offers support to energy investors convinced that today’s weak security prices reflect a far too pessimistic outlook. In fact, we can’t think of a serious forecast of natural gas demand that doesn’t project steady growth for decades. It may not be what progressive Democrats would like to see, but since global energy demand is going to keep growing, we’ll need more of every energy source.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.