The U.S. Lowers Oil Volatility

MLP investors are well aware that energy infrastructure securities move with crude oil, until that relationship inconveniently broke down during the Summer. Although we move and process far more natural gas (on an energy equivalent basis) than oil, investor sentiment causes the link. Because the economic link is weaker than sometimes implied by moves in the sector, the two can part company with little warning.

Some relationship makes sense, because pipelines and related infrastructure are typically built in anticipation of future demand. Commencing pipeline operations at 100% capacity is of course the best case, but more common is a steady ramp-up of utilization. The rate at which capacity gets used up can depend on production levels in the supplying region, and production is sensitive to price.

Before the Shale Revolution, U.S. crude oil production was heading steadily lower. Today, any forecast of U.S. output must be based in part on commodity prices. The correlation between the two is sometimes higher than it should be, but it’s no longer a commodity-insensitive business.

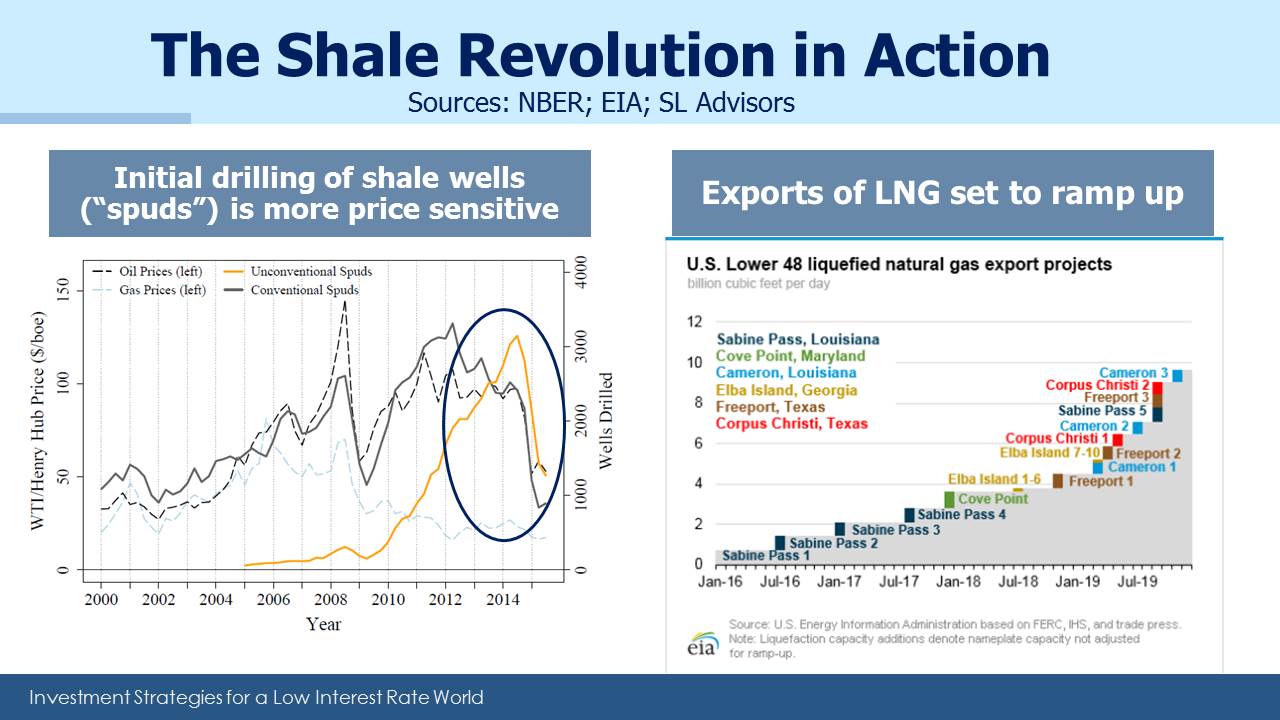

A recent report from the National Bureau of Economic Research (The Unconventional Oil Supply Boom: Aggregate Price Response From MicroData) seeks to measure the sensitivity of U.S. oil production to price. Among their conclusions is that unconventional drilling is up to six times more responsive to prices than conventional. This is because shale projects are “short-cycle”; the payback time is far shorter. Shale drillers can hedge enough of their expected output to ensure an adequate return, not just because upfront expenses are comparatively low but also because initial production rates are high, relative to conventional wells (see Why Shale Upends Conventional Thinking). Exxon Mobil’s CEO Darren Woods commented earlier this year that a third of their capex budget was dedicated to short-cycle opportunities. It’s because they’re less risky. Conventional projects have far longer payback periods, exposing them to the vicissitudes of prices.

The growing importance of short-cycle projects has a couple of other implications for crude oil. One is that it should reduce market volatility. The greater responsiveness to price of shale production means that supply/demand imbalances are more smoothly corrected. NBER doesn’t go as far as to classify the U.S. as the swing producer (which they define as one able to react within 30-90 days), because such adjustments still take several months. But we clearly have a more sensitive supply response function than in the past. Oil prices are becoming less volatile, as we suggested might happen (see U.S. Oil Output Continues to Grow).

NBER’s conclusions include an additional insight, which is that production from unconventional wells is less variable. Not only do you get your capital investment returned more quickly, but you have greater certainty around output. In combination, these two aspects of shale should lead to lower required returns on capital. All of this is to the enormous benefit of the U.S., since shale drilling is almost exclusively an American phenomenon.

Crude prices have been rising as OPEC’s production curbs gradually take effect. Their decisions will continue to significantly impact prices. But another consequence of shale could be gradually rising prices. NBER estimates that a rise to $80 a barrel would stimulate an additional 2 million barrels a day (MMB/D) of U.S. production within two years. Investing in conventional oil and gas projects has been falling, and it’s generally accepted that we need to produce an additional 4-5 MMB/D annually to offset depletion of existing fields as well as meet new demand. U.S. shale may be part of the solution but the figures above show that other sources will need to provide the lion’s share. Earlier this year Goldman Sachs forecast that at $75 a barrel U.S. production would exceed 20 MMB/D. Cleatly there’s enormous variations in forecasts, and NBER may be overly conservative.

Therefore, gently rising crude oil prices are the most likely outcome. This can only be good for U.S. energy infrastructure. Meanwhile, Liquified Natural Gas exports are set to increase sharply. The constructive analysis on crude oil prices doesn’t apply as readily to natural gas, because global LNG trade volumes are benefiting from several new sources of supply. But as one of the lowest cost producers, the U.S. is in good shape here as well.