The Stock Market’s Heartless Optimism

Last week in our local paper, the Obituaries section ran to three pages. 17 people were listed. 14 of them were over 80, and three were in their 60s. The steady drumbeat of death, economic destruction and lockdown is why the stock market looks as if it’s divorced from reality. The S&P500 is only down 11.7% for the year, after being up 31% in 2019. In late March it briefly dipped below 2,200, where it registered -32% YTD. If instead it had simply spent the last four months meandering down to its present level, performance would be just moderately poor.

The stock market may not be right, but the collective outlook of investors is that we’re enduring an economic blip that will pass within a year or so. Bottom-up S&P500 earnings forecasts are for next year to be higher than last year – and 2021 earnings forecasts have already been revised 12% lower since January.

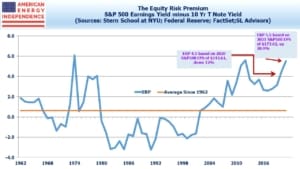

The news and the mood are terrible. The stock market is heartless, but is it also irrelevant? If earnings come in as expected next year – admittedly still a big “if” since revisions continue to be down – stocks are cheap. The Equity Risk Premium (ERP — S&P500 earnings yield minus ten year treasury yield) is at the levels of the 2008 financial crisis, even following a 27% rebound from the March lows. Unless 2021 earnings are revised down substantially, the relative attraction of stocks will draw them still higher. If the market keeps rising, the resulting headlines will coincide with, and perhaps cause, a lifting of the popular mood.

What is the cold-hearted analysis that’s reflected in today’s valuations? What follows is not a run at amateur scientist, for which we’re not qualified. It’s a virus-driven upside explanation for stocks.

As much as it pains me to write this, and with deep sympathy for the many families who have lost a loved one, the fact is that not that many people are dying. In two months, 50,000 Americans have died from Coronavirus. We probably undercounted somewhat at the beginning, and it’s likely the virus was killing people as early as January. We may be overcounting now, because if a patient dies with Coronavirus it’s more likely to be recorded as the cause of death even if they suffered from other, serious illnesses.

In 2018, the CDC reports 2,839,205 deaths in America. People are a bit more likely to die in the winter, but on average around 7,780 people die every day. Over the past two months, we would have expected just over 473,000 deaths anyway. The 50,000 Coronavirus-attributed deaths is, without doubt, 50,000 too many. But the demographics are by now widely known to be heavily weighted towards older people, just as in our local paper’s Obituaries section. The virus is denying as full a life as all these people deserve, but its lethality for younger people overwhelmingly relies on other serious health conditions.

One bright spot is that the most recently weekly CDC figures report only 62% of “Expected Deaths from All Causes”. This is partly because nobody is driving anywhere, so road deaths are down. On average, 730 people die every week in car accidents. The fortunate souls who are alive thanks to lockdown don’t know who they are, but they’ll be consuming products and services for many years to come.

The infection numbers are largely useless, because in the U.S. we’ve only tested 1.4% of the population and you generally have to be sick to get a test. 5.7% of those who tested positive have died, a catastrophically high figure. However, serology tests which look for antibodies as evidence of prior infection are implying that Coronavirus has spread much wider than as measured by reported infections. Lots of people suffer mild symptoms or even none at all (they are “asymptomatic”). Results from LA County and Santa Clara in California suggest the true infection rate is 50X higher in those regions. New York City estimates that 21% of its residents have been infected.

An infection rate fifty times higher means a fatality rate fifty times lower. At the outset, health professionals told us that the vast majority of us weren’t in mortal danger from contracting it. This seems to be true. Economically, that brings a return to new normal closer. The many constraints on our liberty and enormous economic damage have been imposed not to protect everyone, but to prevent the small percentage who will require hospitalization from overwhelming the system (‘flatten the curve”). Widespread compliance has been an enormously selfless act, but this has its limits and we’ll transition to more targeted means of protecting our most vulnerable citizens. Earnings forecasts dispassionately reflect that.

It also means that society will learn to live with Coronavirus long before everybody’s been vaccinated. This is not a widely held view. If the fatality rate is 5%, we’re all going to want a vaccine as quickly as possible. Shortening the testing period and taking some risks with side effects is a worthwhile trade-off. But if the fatality rate is less than a tenth of that, and maybe as low as the flu at 0.1%, widespread vaccination will occur at a more measured pace. Higher risk groups such as the elderly will derive more benefit, even from a vaccine that’s not been subjected to normal testing. But if you’re young and healthy, medical authorities will determine that the years-long testing schedule remains appropriate. A vaccine that’s used prematurely would lower participation in all types of vaccination program, creating a real health catastrophe. And many people may decide for themselves to wait until the Coronavirus vaccine has been widely used safely, with no meaningful side effects. Only half the adult population gets an annual flu shot. It could be several years before a Coronavirus vaccine reaches a sizeable majority of Americans.

Most pipeline companies have maintained guidance at or close to prior levels. Cuts in growth capex more than make up for lower expected cash flow from operations, which will support their free cash flow. Kinder Morgan raised their dividend by 5%. Other large cap companies including Enbridge, Enterprise Products, TC Energy and Williams (all members of the American Energy Independence Index) have maintained payouts, even though every company has a free pass on cutting dividends right now. Like the rest of big American business, midstream energy infrastructure companies are assessing their own outlook, and it’s not as dire as the news.

The virus could take an unexpected turn. We have no scientific insight to offer on that. But today’s market reflects today’s facts as we know them. Rather than the stock market not reflecting reality, maybe it’s telling us to be more optimistic.

We are invested in all the stocks mentioned above.