The Slow Death Of 60/40

On the weekend the WSJ highlighted contrasting views of the 60/40 portfolio between Goldman Sachs and Blackrock. The classic asset allocation had its worst year in nominal terms since the 2008-9 Great Financial Crisis (GFC) and adjusted for inflation the worst since the Great Depression.

It shouldn’t be a surprise. Bond yields have been too low to justify the discerning investor’s capital for many years – a point I made in my 2013 book Bonds Are Not Forever: The Crisis Facing Fixed Income Investors.

The Federal Reserve owns $7.3BN in treasury bonds and Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS). These holdings are a result of Quantitative Easing (QE), which Ben Bernanke first unleashed in response to the GFC. At the time this was a controversial move that many (including me) thought would be inflationary. Bernanke understood better than anyone how the monetary system would respond. It was a unique moment and QE should have been a one-off.

But in 2020 Jay Powell took it to a new level before the prior QE holdings had run off. Now one must conclude that any economic downturn will be met with Fed balance sheet expansion. The current lethargic pace of balance sheet reduction will likely be reversed with the next recession. This partial debt monetization is becoming permanent. It’s a consequence of too much debt.

Japan is the biggest foreign holder of US treasuries with $1.1TN. China is second at $0.9TN. Along with the Fed, for these investors a return ON capital is unimportant – they want a return OF capital. The old fear that China might dump their holdings is irrelevant with QE. Selling a $1TN of bonds would be destabilizing, but who now doubts the Fed would step in and take the other side?

Inflexible investment mandates that require fixed income allocations regardless of return prospects are another source of excess demand for bonds.

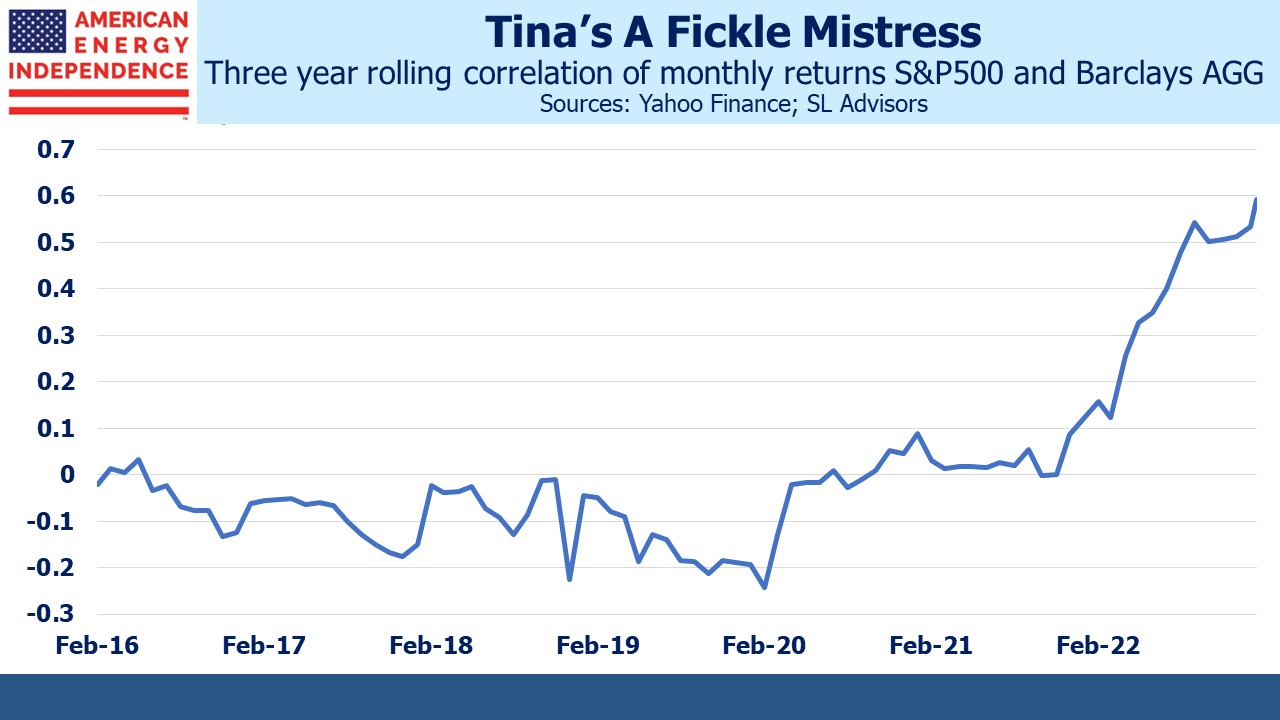

The result is that return-oriented bond investors are competing with substantial capital disinterested in a return. Bonds had some good years following the publication of my book warning investors to take their capital elsewhere. The adjustment away from fixed income is slow. But last year was a wake-up call. Paltry yields left diversification as the only justification for owning bonds. But their correlation with stocks has been rising sharply. The ascendancy of TINA (There Is No Alternative) caused this. The tyranny of pygmy interest rates and consequent shift to equity risk increased the stock market’s vulnerability to rising rates.

Over the past decade the Barclays Agg returned just 1.3% pa, versus 12.2% for the S&P500.

Today’s higher yields suggest a better decade ahead. But much depends on inflation. At 3.5% the ten year treasury note offers just 1.5% above the Fed’s long term inflation target of 2%. This is below the real return of the past hundred years. And it relies on inflation quickly returning to 2% and remaining there.

Inflation expectations are encouraging. Like many banks, JPMorgan expects falling inflation this year and is forecasting CPI of 2.8% in 4Q23. Ten-year TIPs yield 1.3%, implying a 2.2% embedded inflation rate in the bond market. The University of Michigan consumer survey regularly confirms this benign outlook.

The broad consensus on price stability isn’t easily ignored. It’s possible that return-insensitive buyers noted above are distorting the message unconstrained bond yields might offer. But Wall Street analyst and household views are harder to explain away. Nonetheless, having endured two years’ of high inflation a cautious investor should assume something above 2% in the future if only to compensate for the risk that these forecasts are wrong. A saver assuming her annual living expenses will increase at 3% into retirement will quickly find equities offer the only hope of keeping up.

60/40 was finished years ago. I haven’t owned a bond in probably two decades. There’s no point. Neither do any of our SMA clients. Instead they hold cash as a diversifier. 90-day treasury bills averaged 0.8% over the past decade, 0.5% less than the return on the Barclays AGG over that time but with no risk. Cash is a risk enabler. It supports increased exposure to equities which is the only chance savers have to maintain purchasing power. Bonds offer risk with an inadequate return.

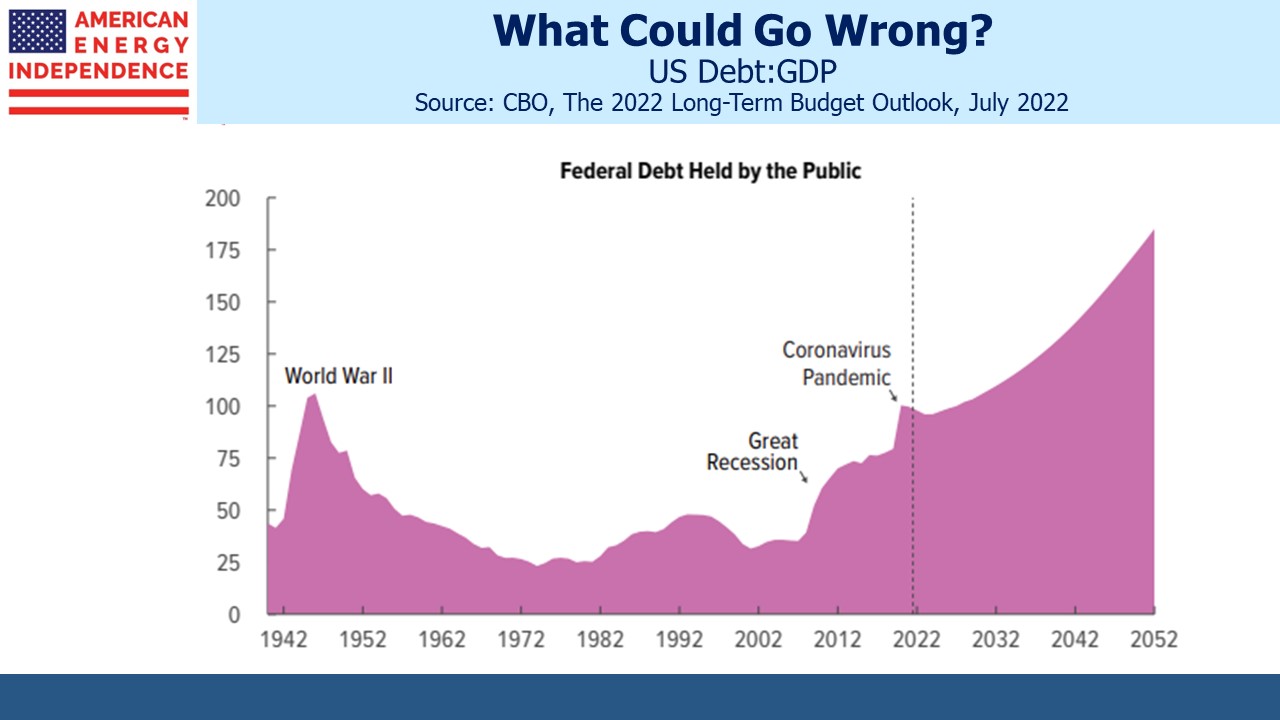

Yields are still too low. The Congressional Budget Office forecasts sharply rising Debt:GDP over the next thirty years. US taxpayers are benefiting from investor inertia, since long term yields aren’t commensurate with the debt outlook.

In BlackRock vs. Goldman in the Fight Over 60/40, the WSJ finds Blackrock believes it outmoded while Goldman defends the indefensible. However, Goldman’s asset management business asked Is the 60/40 Dead? in October 2021 and warned “investors should at the very least recalibrate expectations.” Even within Goldman Sachs, reasonable people can disagree.

For more on how a combination of stocks and cash can replace fixed income, see The Continued Sorry Math Of Bonds, which we published around the same time. Adding midstream energy infrastructure to the equity portion of the stocks/cash barbell will, in our opinion, further boost its performance.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment: