The Midstream Earnings/Valuation Paradox

Midstream is mercifully removed from all the angst and excitement of AI stocks and crypto – although in a modern version of selling pickaxes to goldminers, natural gas and its infrastructure enable much of this activity. You have to admire the response of MicroStrategy CEO Michael Saylor to the bitcoin collapse which has crushed his stock price.

“Volatility is Satoshi’s gift to the faithful” said Saylor recently, invoking Satoshi Nakamoto, the pseudonym attributed to bitcoin’s founder. Such uber-confidence would badly shake mine if I was invested with Saylor.

But it’s safe to say that our risk appetites have little in common. I have no bitcoin and only wish the best for my friends who do. Tangible assets with well covered dividends that are growing are our thing.

To invoke Ben Graham, crypto is for those who rely on the stock market as a voting machine, while midstream is for those who use it as a weighing machine. For the latter, including your blogger, the spread between a company’s Return On Invested Capital (ROIC) and its Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) provides enduring excitement.

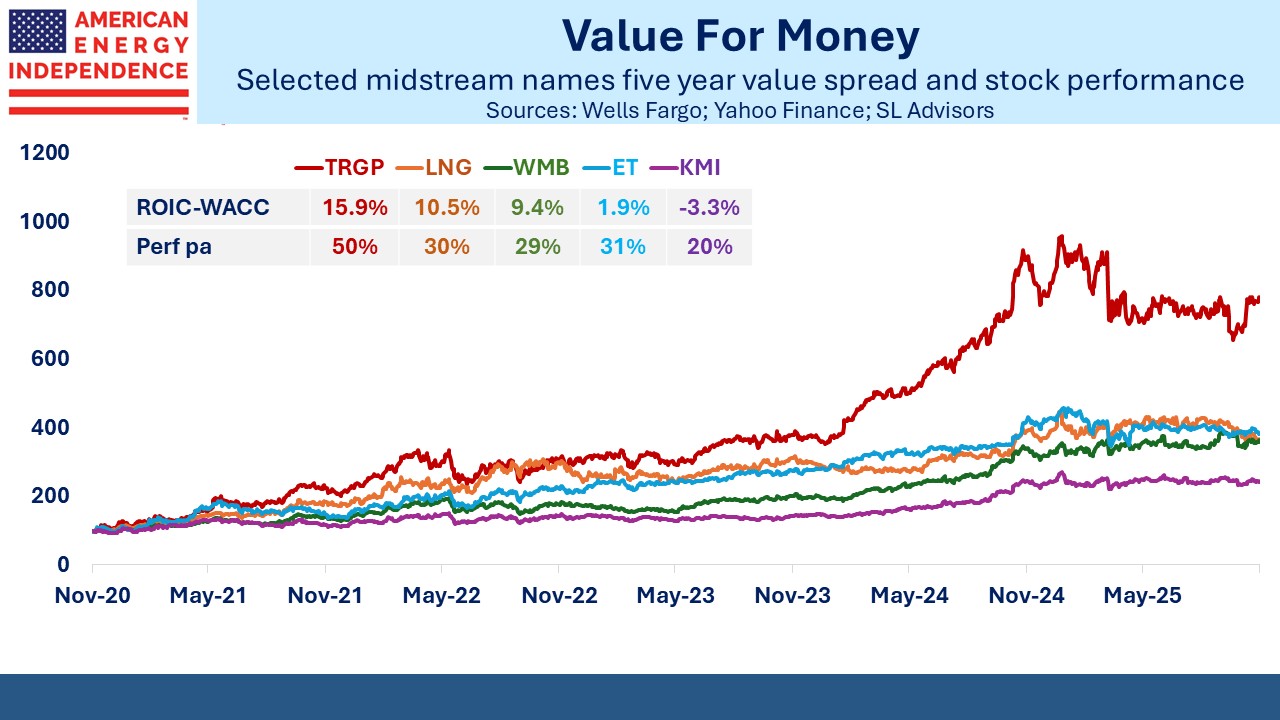

Recent figures from the Wells Fargo Show Me The Money report, when compared with stock price performance, illustrate a solid relationship. Targa Resources (TRGP), Cheniere (LNG) and Williams Companies (WMB) all show a healthy spread between what they pay for capital and what they earn on it.

Kinder Morgan continues to prove that when management discusses “growth capex opportunities,” investors should prepare for more capital misallocation.

Commensurate stock price performance followed.

Energy Transfer has combined a relatively low spread with decent stock performance, which is probably due to its very low price five years ago as we came out of the pandemic, flattering returns. Nonetheless, even today the 8% distribution yield 2X covered by Distributable Cash Flow looks like a glaring market oversight, as improbable as that sounds for a company with a $56BN market cap.

The one year total return forecast for ET is 38%, 35% and 45% at JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley and Wells Fargo respectively.

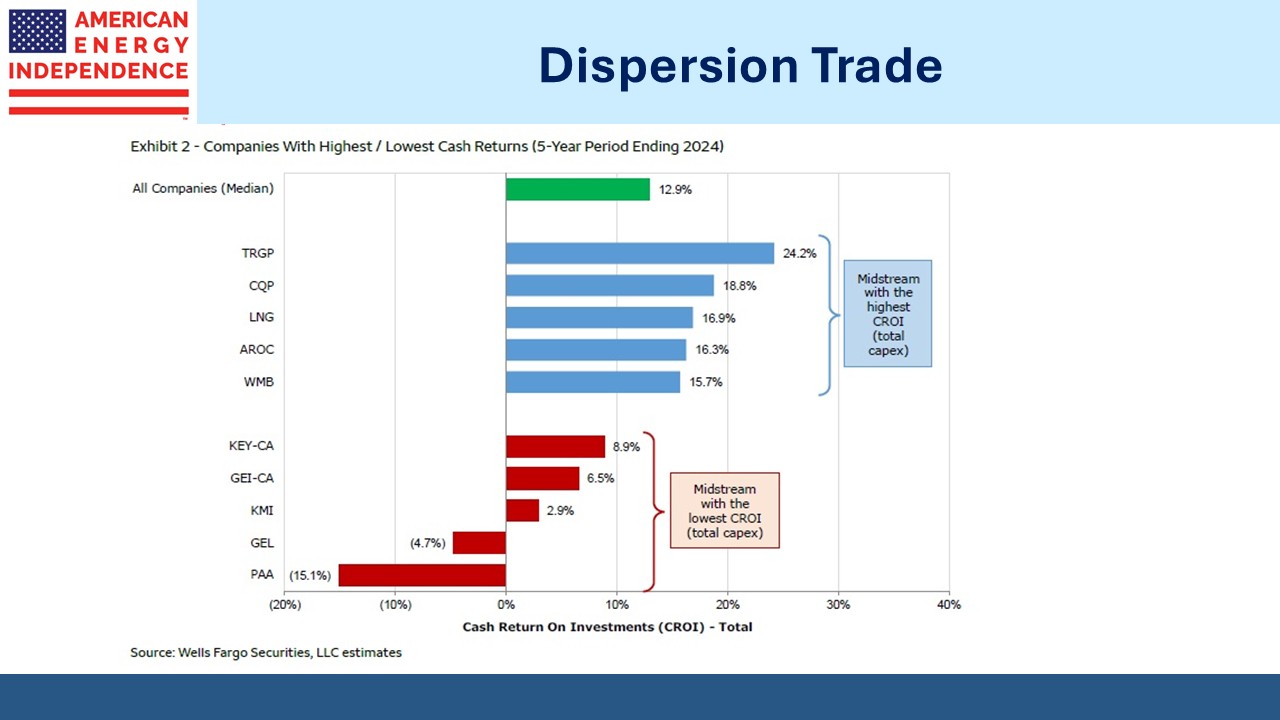

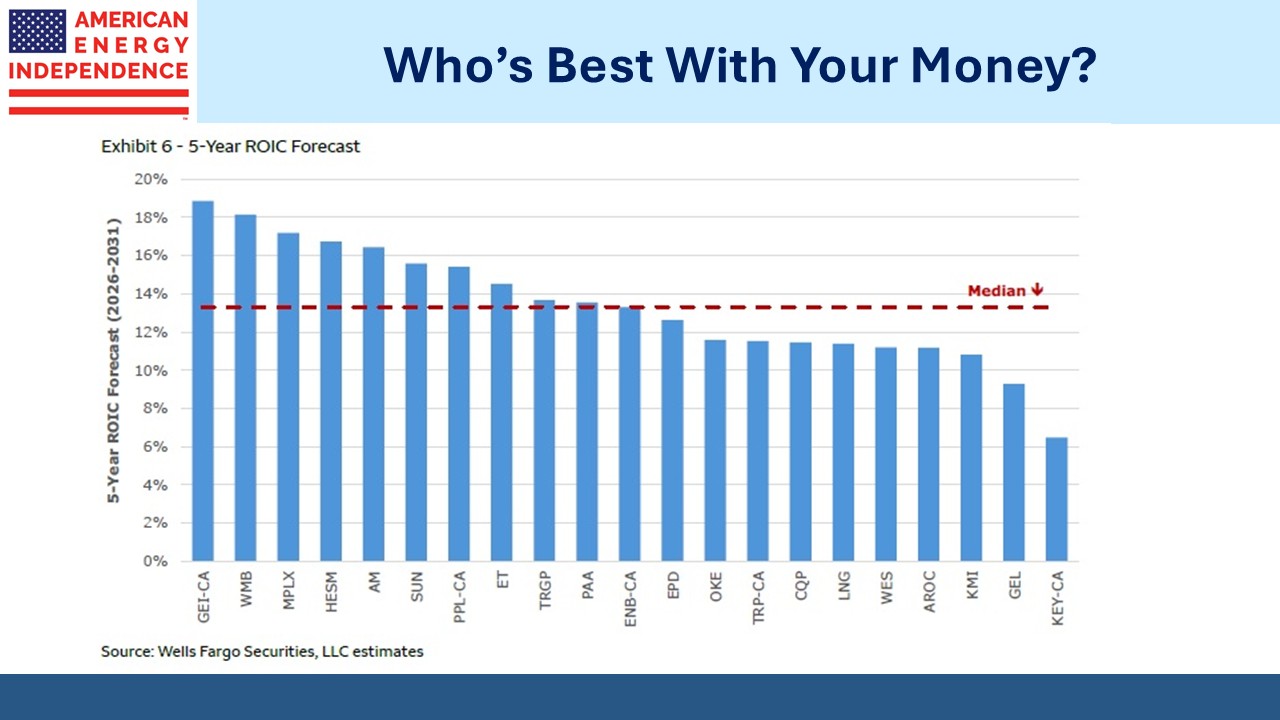

The difference in ROIC over the past five years across companies is surprisingly large given the predictability of cashflows in the industry. Wells Fargo now forecasts ROIC for the next five years and unsurprisingly expects persistence in the skill that capital allocators exhibit.

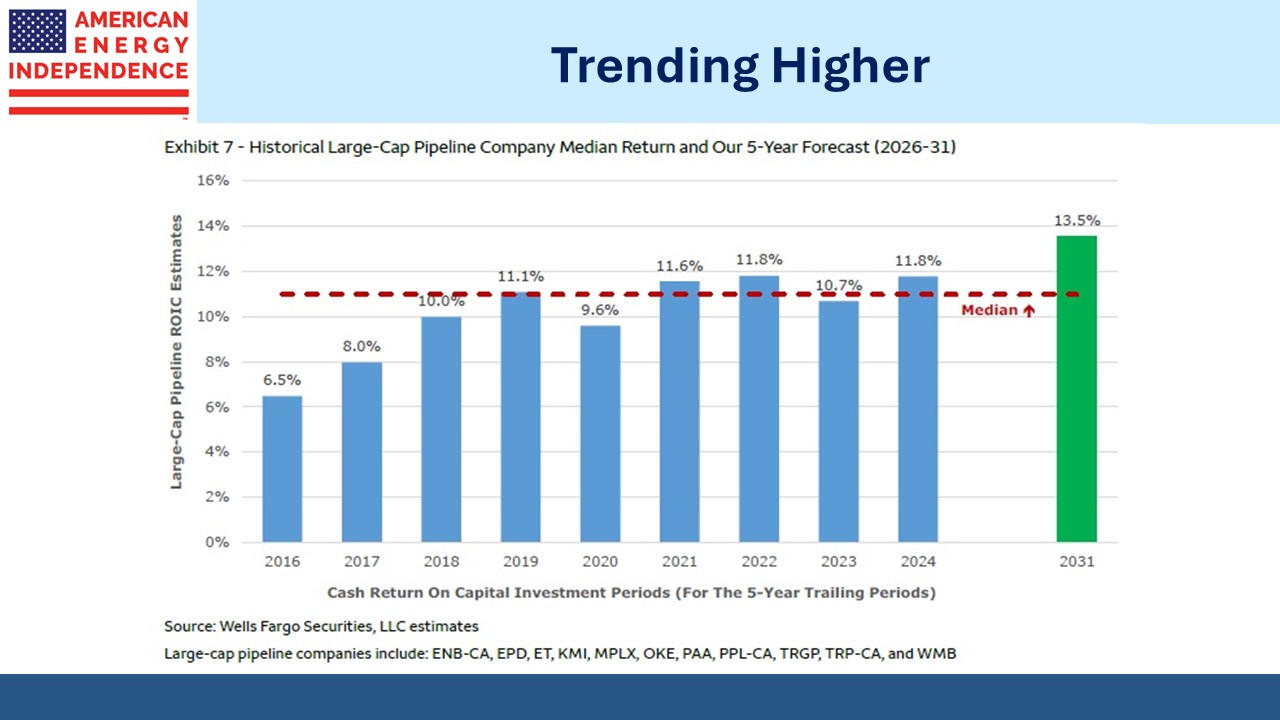

As a group, midstream companies are improving at deciding which projects to finance. The shale revolution represents the nadir, with the five year periods ending in 2016 and 2017 especially poor. The most recent lustrum* equaled the 11.8% record set in 2022.

Encouragingly, Wells Fargo expects the period ending in 2031 to produce a median ROIC of 13.5%. Oil and gas volumes are growing. Data centers are sprouting up everywhere to support the AI revolution. Behind The Meter (BTM) deals that provide natural gas directly to a dedicated power plant, bypassing the grid, are proliferating. Wells Fargo counts 4GW of BTM deals that have reached Final Investment Decision, up from 2GW in July. This will continue to ramp up.

Exports of liquefied natural gas will double by 2030. So far in 4Q25 they’re running at 16.2 Billion Cubic Feet per Day (BCF/D), up from 13.3BCF/D in 4Q24.

The projected ROIC could be wrong. Perhaps some capital will be committed too exuberantly, in a re-run of a decade ago. But it’s also possible that today’s valuations are wrong. Companies have discovered the virtue of capital discipline with its concordant impact on stock prices.

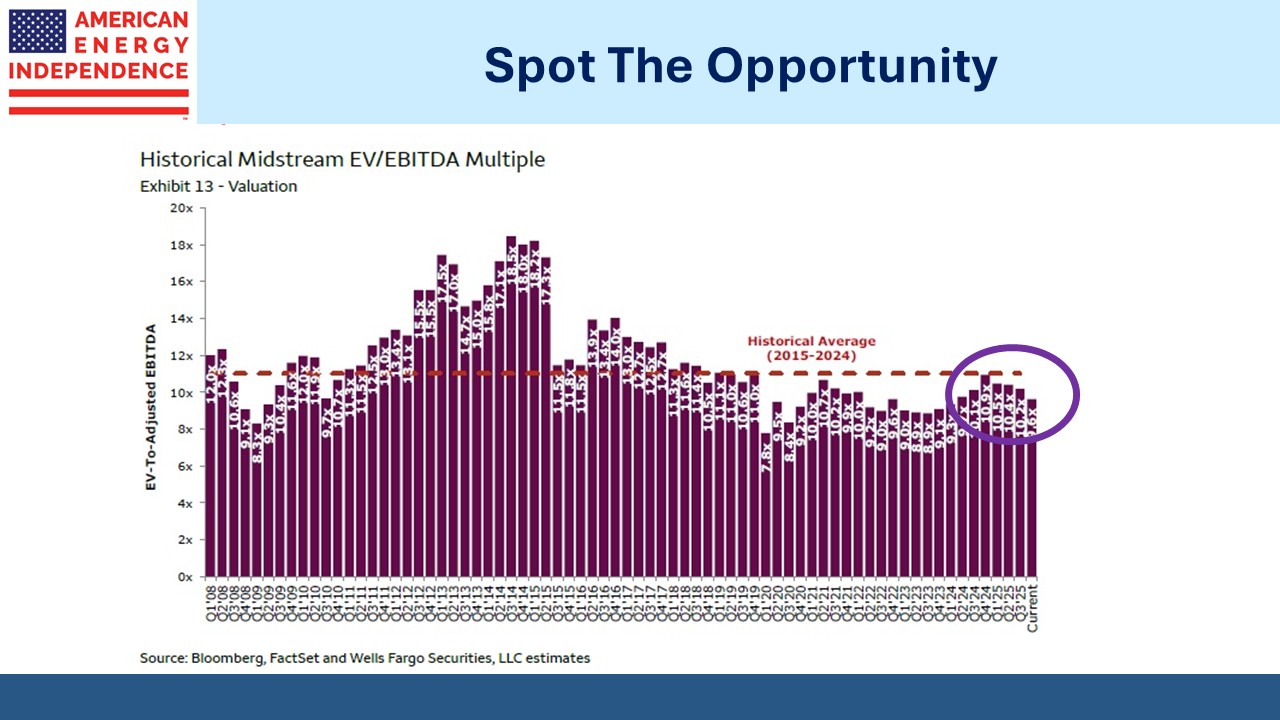

Therefore, it’s a paradox that Enterprise Value/EBITDA (EV/EBITDA) has weakened to 9.6X, well below the ten year average of 11.0X. Market prices are implying an ROIC substantially below the Wells Fargo forecast and probably below the median of recent years. A move up in EV/EBITDA from 9.6X to 10.6X would increase enterprise values by around 10% and equity values by twice that given the roughly 50/50 equity/debt split that prevails.

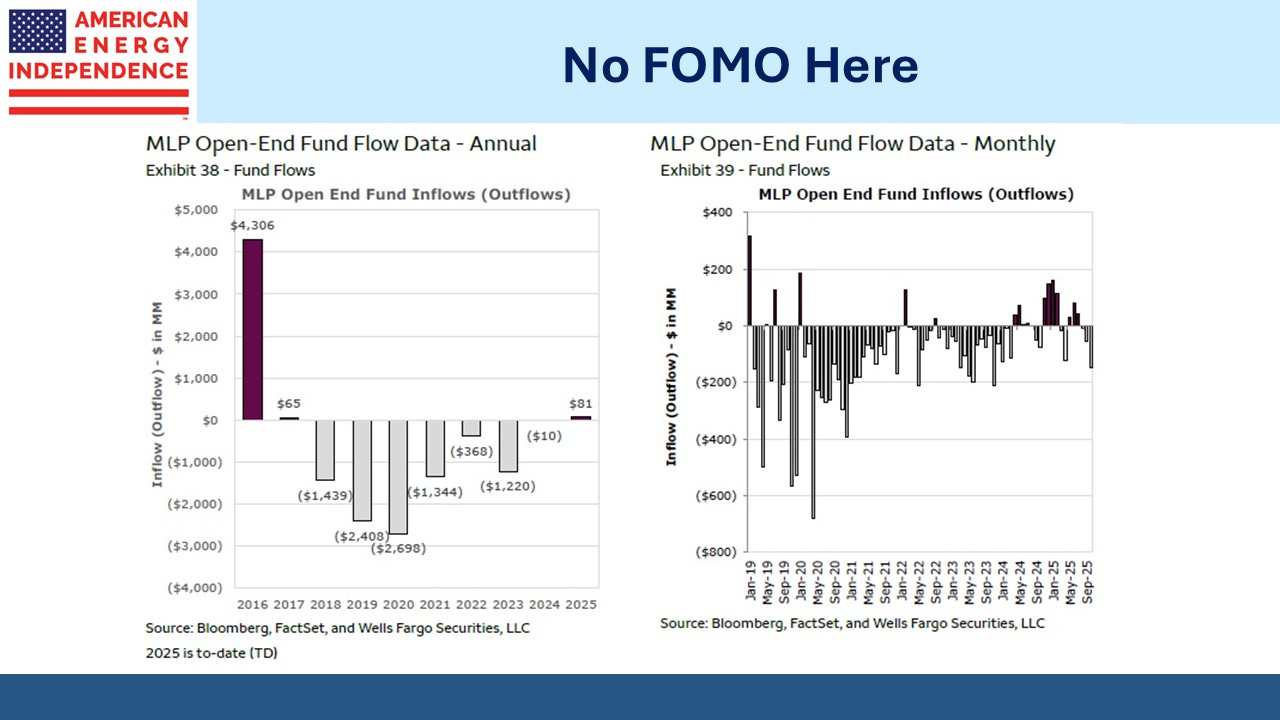

Fund flows are barely positive for the year, with recent months offsetting inflows in 1Q25. This year might yet break a streak of seven consecutive years of outflows.

The combination of growing volumes, improving capital allocation and twin demand drivers for gas might ordinarily induce value-driven investors to buy. This is a sector of tangible assets full of concrete metrics well suited to the weighing machine type of investor.

To paraphrase Michael Saylor, today’s attractive valuations are a gift to the discerning investor. The breathless excitement of crypto and AI commands the attention of many. When they start voting their money differently, we suspect that stable dividends will become fashionable once again.

Pipeline investors are used to being paid to wait. It’s only boring over the short run.

Recently, long-time investor Emerson Fersch interviewed me to discuss the history of midstream and its outlook. You can watch it here.

*A lustrum is half a decade.

We have two have funds that seek to profit from this environment: