The High-Priced Energy Transition

“Thankfully, energy has been the bright spot in our client portfolios,” said investor Emily Jaffe. We had just sat down to enjoy a most convivial lunch with Emily and her business partner Jeff Waters of OFC Wealth Management. In the photo below we are toasting the performance of the pipeline sector this year.

Superstition has its place in finance. Mindful that we might be marking the energy sector’s top with such reckless good humor, we all pledged sincere fealty to the market gods. Several minutes were spent in a roundtable of penance lest we provoke the deities to impose groveling humility for daring to enjoy the moment. Energy investors have plenty of scar tissue, most notably from the March 2020 Covid collapse. We all well remember how dire the outlook appeared back then. .

A question we’ve pondered recently is what the possible political consequences of resurgent energy markets are. 20 million US homes are behind on their electricity bills, around one in six residential customers and the worst ever crisis in late utility payments. US natural gas recently touched $10 per Million BTUs, a level not seen since the shale revolution unlocked vast domestic quantities of the resource.

In spite of high prices, US power generation from natural gas hit a daily record in mid-July. Less than a year ago the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) was forecasting that utilities would switch back to coal, reversing a near two-decade trend that is the source of most of America’s drop in CO2 emissions. But measured by the Producer Price Index (PPI) US coal prices are up nearly 60% seasonally adjusted this year, a sharper move than for natural gas. As a result there’s been less switching back to coal than the EIA expected.

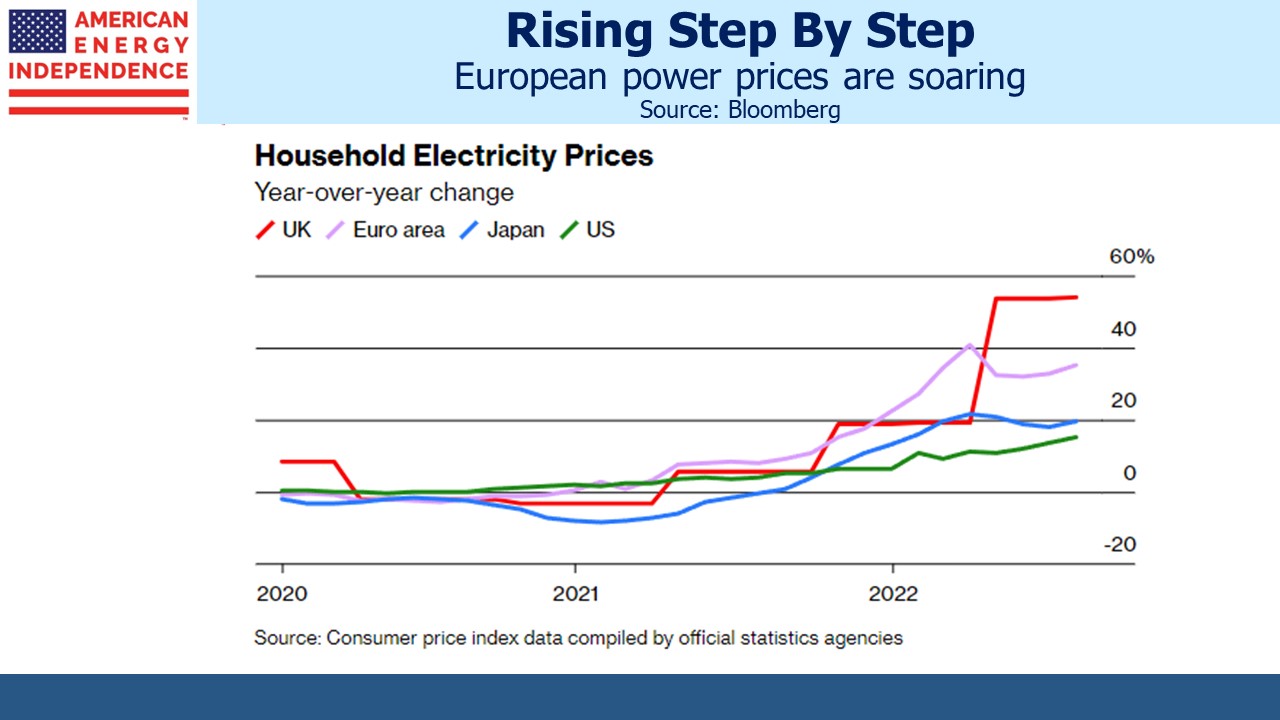

Residential energy bills are regulated in most countries. Eventually power providers are allowed to pass through cost increases but there’s a delay. Utility bills are headed higher.

As painful as this is for US households, it is much worse in Europe where natural gas and wholesale power prices are 7X or more than our own. The UK regulator Ofgem has been forced to concede regular large increases in the cap on the typical household energy bill. By next April it is expected to be 4X the level of two years earlier (see America Dodges The Energy Crisis) where it will consume 16% of the typical British household’s income.

A political backlash seems inevitable and justified. Italy is often perceived as the weak point in any EU crisis. Hedge funds currently have the largest short positions in Italian government debt since 2008, betting that the country’s fractious politics are ill-suited to confront popular dissatisfaction with energy bills. Most EU countries are providing subsidies to low income families and cutting energy taxes.

Policymakers will blame high energy prices on the rebound from Covid and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Germany catastrophically adopted the role of energy supplicant to Russia with the misplaced hope of drawing them closer. The unraveling of this strategy is the proximate cause of Europe’s energy crisis.

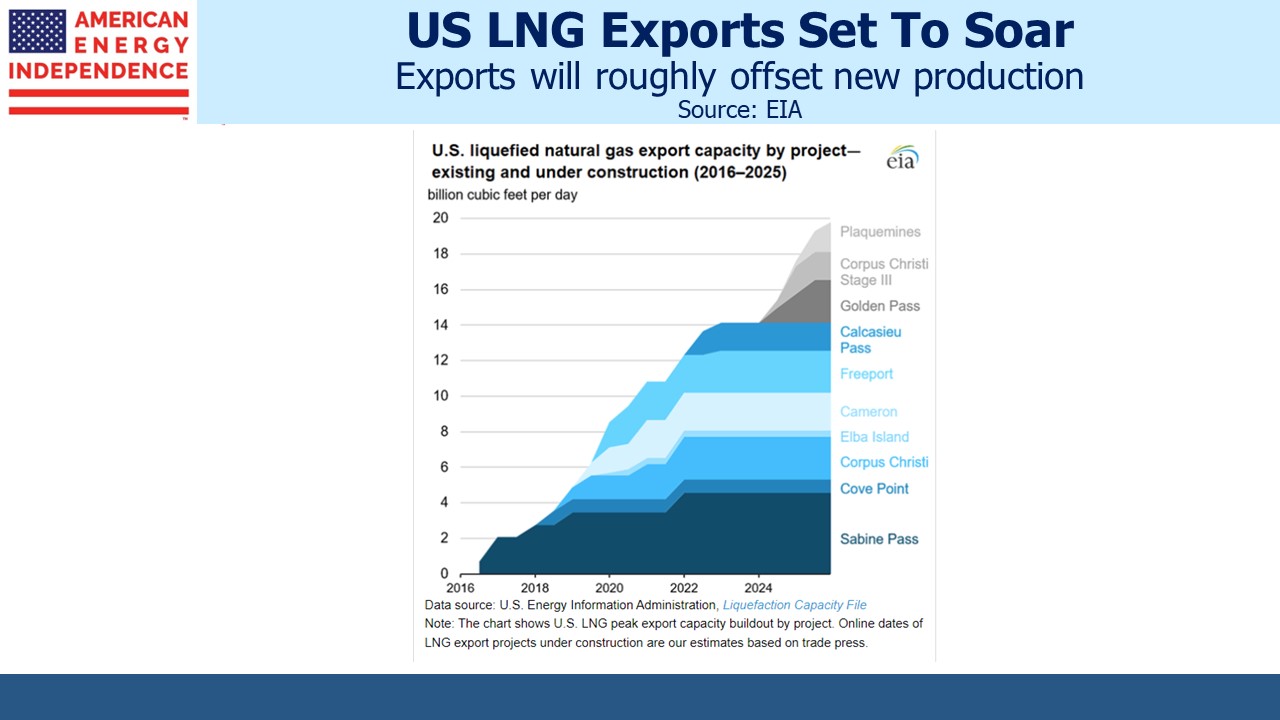

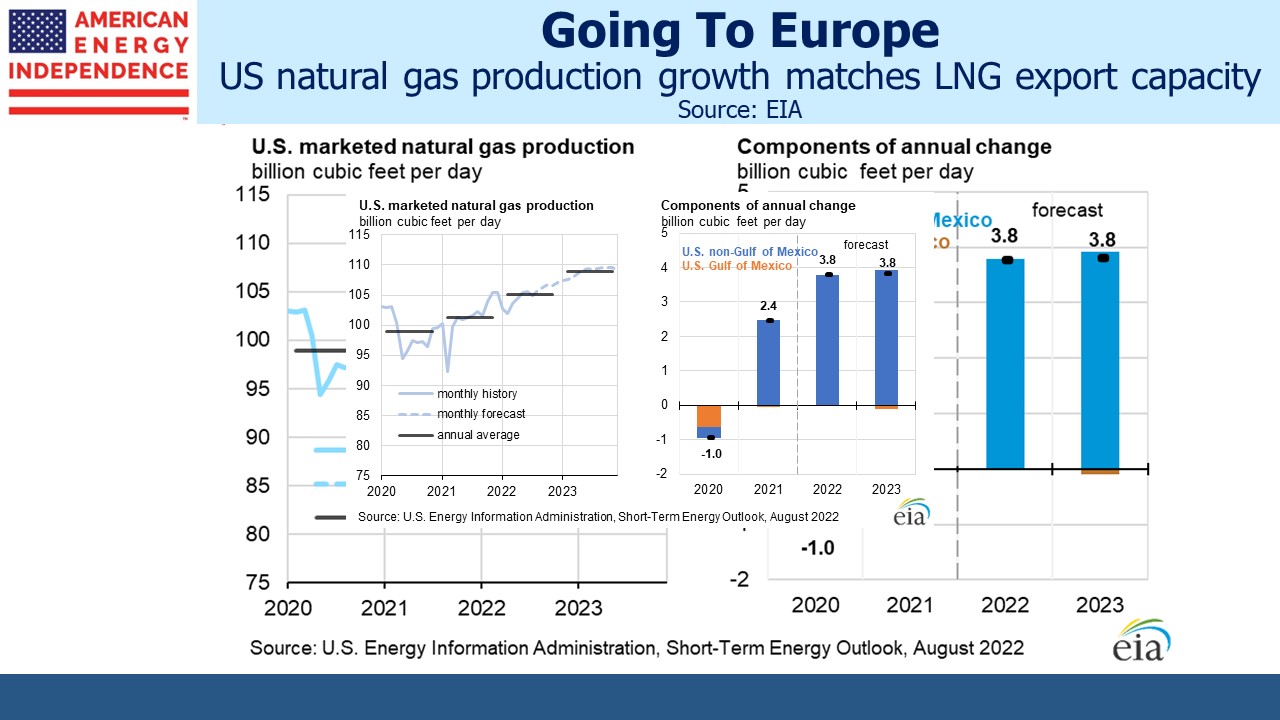

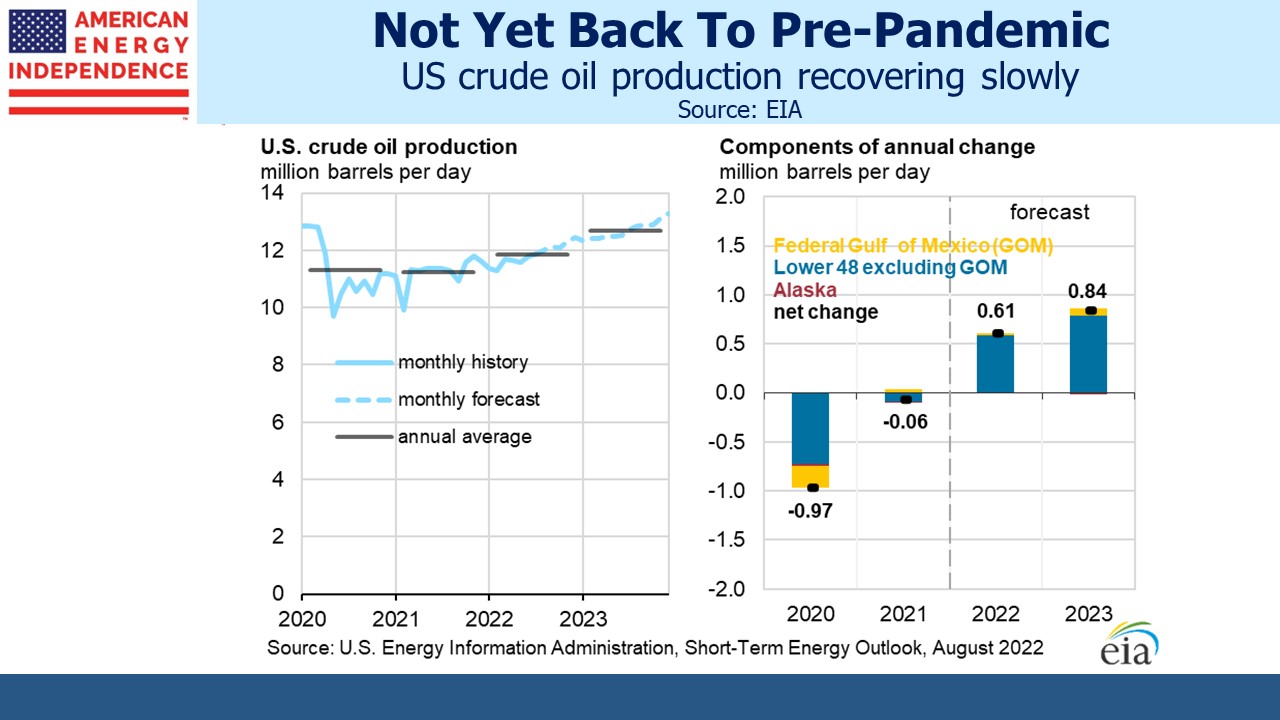

But investment in new oil and gas production has become more risky with the west’s pursuit of solar panels and windmills. US production of crude oil will not reach the pre-pandemic level of 2019 until next year. US natural gas production is growing roughly in line with LNG export capacity, leaving domestic supply unchanged. President Biden has pledged to provide natural gas to Europe, but he’s not doing anything to help US households. Exports are likely to absorb any increase in domestic production.

Energy companies also face the prospect of a windfall profits tax, which won’t provide much inducement to invest in additional supply.

So the big question is, will public opinion correctly assess that persistently high energy prices are caused by falling investment in new oil and gas production? The vilification of “big oil” by governments and ESG proponents has led to increased caution around growth capex. Will voters conclude that the Democrats have oversold the energy transition, over-promising the ability of intermittent power (solar and wind) while ignoring China pumping out additional CO2 that’s swamping whatever reductions western countries are achieving at already great expense?

Today’s pipeline sector is positioned to be an important part of the solution, both to high energy prices and reducing emissions. Utility bills will increasingly command attention as past policy errors hit family budgets. We’ll soon see if there are political consequences. The investment consequences have been good.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Please see important Legal Disclosures.