The Flexibility of MLPs

A couple of weeks ago we came across a research note from Wells Fargo titled “Do MLPs Still Make Sense?” Their conclusion was a qualified “Yes”, although it’s not wise to be highly negative when you have a thriving business underwriting their equity offerings.

Last year’s collapse in the sector provoked the question. In our view, this wasn’t so much an issue of operating performance but one of financing growing capital expenditures. As we wrote in The 2015 MLP Crash; Why and What’s Next, the Shale Revolution has led to a substantial increase in the demand for new energy infrastructure, since the new reserves of hydrocarbons are not always well served by the traditional infrastructure configuration (i.e. North Dakota was only recently a significant region for crude oil production; similarly so for Pennsylvania and natural gas).

By 2014 the needed cash to finance this growth exceeded the cash generation capacity of the MLP sector. Since MLPs don’t retain earnings, they mostly tap the capital markets for such finance. The multi-year nature of many projects led to a “just-in-time” philosophy around financing in the same way manufacturing businesses maintain minimal supplies of inventory to limit their need for working capital. A temporary closure of the capital markets as the most recent MLP investors (mostly ETF and mutual fund buyers) fled late last year exposed this model. MLPs have taken many steps in response including greater distribution coverage, less leverage and higher return targets on new projects. They’ve adapted.

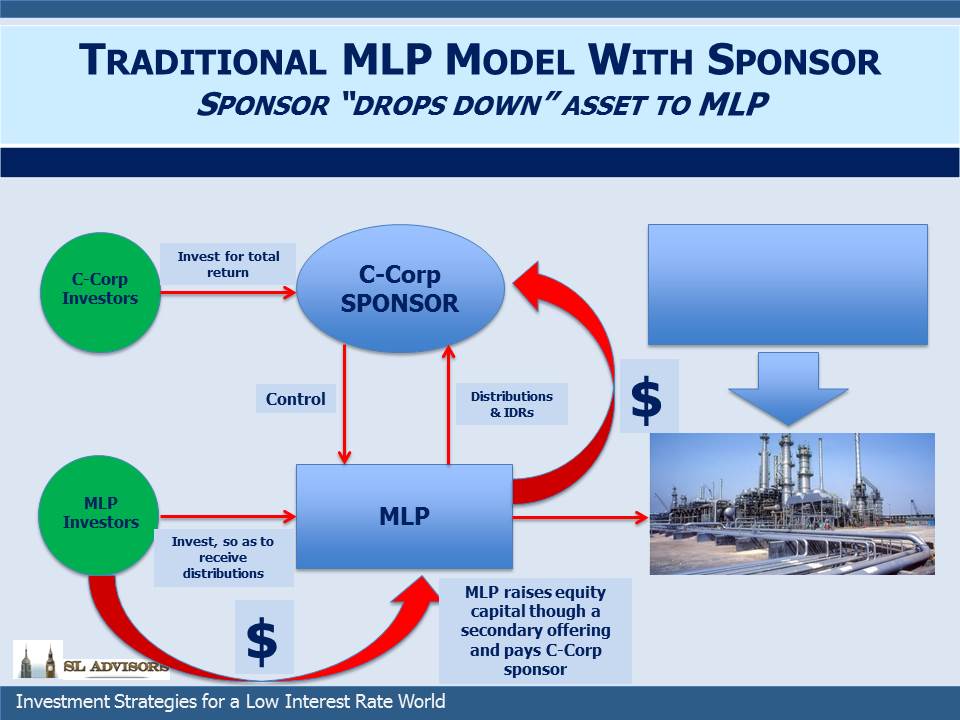

It really comes down to whether the Master Limited Partnership structure combined with the General Partner is the best way to finance the assets. Since MLPs are pass-through vehicles with no tax liability, it’s hard to improve on a tax-free structure as the holding vehicle. Any corporation holding eligible assets will be subject to Federal corporate income tax on the profits, which is why a common maneuver is to “drop down” those assets from a C-corp parent into an MLP. The C-corp often retains control through its GP interest in the MLP, and shares in the future economics without providing the capital. The retained connection can be value-enhancing for both entities. An Exploration and Production (E&P) company can finance its E&P assets as a C-corp where capital is cheapest, but still control the infrastructure critical to supplying its customers while using cheaper, MLP capital. Examples include Devon Energy (DVN) with Enlink Midstream Partners (ENLK) and Anadarko Petroleum (APC) with Western Gas Partners (WES). The MLP/GP structure often exists as a symbiotic relationship.

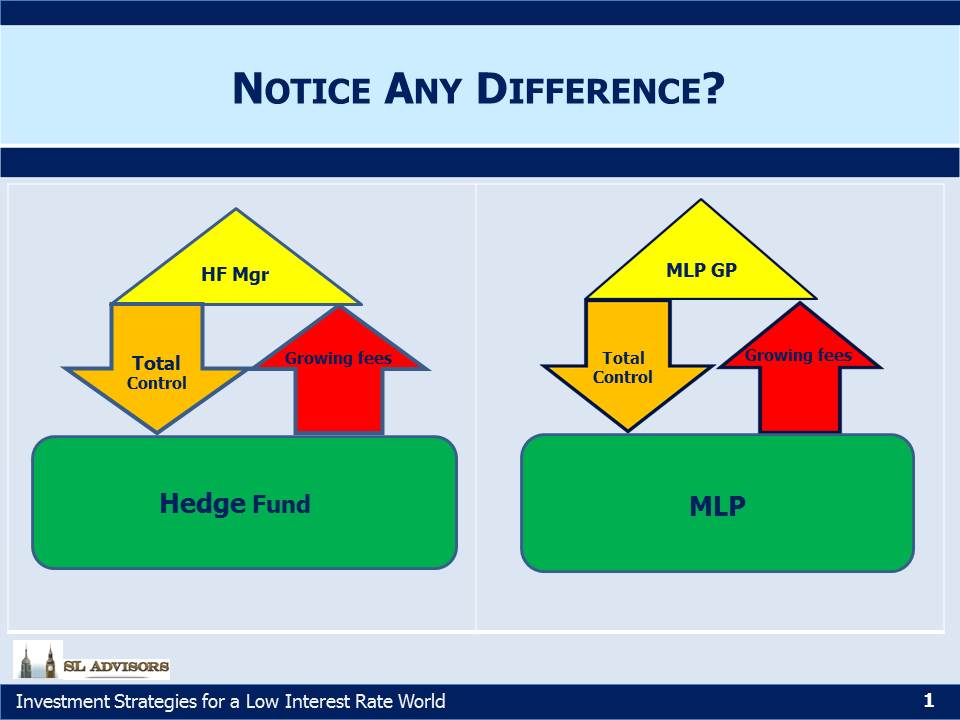

There are many analogous financing structures to be found. As regular readers know, we like the comparison with hedge funds and private equity, where the MLP is the fund and the GP is the hedge fund/private equity manager. The fees paid to the manager clearly take away from the returns earned by the investors – indeed, in the case of hedge funds, spectacularly so as I have often noted (see The Hedge Fund Mirage). However, the size and history of alternatives (hedge funds, private equity and real estate) confirm that a substantial pool of capital is available to finance assets that require active management with payments to the operators. MLP investors are in many ways better off than the investors in these private partnerships; they have the liquidity to sell whenever they want, their investments are subject to all the disclosures of publicly listed companies, and the ten year annual return of 9% is better than REITs, Utilities, the S&P500, Bonds and, most assuredly, hedge funds.

Another analogy is with companies that have two or more classes of equity outstanding. Alphabet (GOOG) and Facebook (FB) both sold shares to the public that allowed the founders to retain substantial control. You’re unlikely to see an activist acquiring a position in these two companies when their performance stumbles, because voting control doesn’t lie with the public shareholders. Clearly, to a substantial number of investors this passive ownership is no barrier. GOOG has returned 12.5% p.a. over the past decade, better even than MLPs.

From time to time investors ask us whether GPs are more volatile than MLPs, and therefore more risky. The history on this topic doesn’t go back that far, because only in recent years has a sufficient number of MLP GPs been publicly available to create a portfolio. Our own Separately Managed Account strategy (which focuses on GPs) has outperformed the Alerian Index by 4.0% p.a. since inception, albeit with modestly higher volatility (20.6% versus 19.8%). Last year certainly saw cases of GPs falling more than MLPs; perhaps most memorable was the 80% collapse in Energy Transfer Equity (ETE) from June 2015 to April 2016. This was mostly due to the ultimately failed effort to merge with Williams Companies (WMB), but nonetheless is now part of the historic performance of MLP GPs.

Financial performance of MLP GPs is highly correlated with the MLPs they control but not obviously more volatile. GPs can exercise substantial control over their cashflows by, for example, directing their MLP to raise capital or divest assets. Moreover, most MLPs today are investing in new infrastructure in support of the Shale Revolution. This increase in their assets will continue to benefit their GPs, similarly to how hedge fund asset growth directly profits the hedge fund manager. If you could buy a hedge fund manager knowing his assets would be growing, how much concern would you really feel over the volatility of his cashflows given that they’ll be increasing?

Finally, MLPs can get too big. Like hedge funds, beyond a certain size it can be hard to generate attractive returns while still growing. There is, in effect, a lifecycle to MLPs. Kinder Morgan (KMI) most obviously demonstrated this. Their solution, to collapse their structure back into a C-corp, was inevitable in hindsight if clumsily executed (see Rich Kinder’s Wild Ride). In 2014 when KMI acquired the assets of Kinder Morgan Partners and El Paso, its two MLPs, the stepped up cost basis created a substantial tax shield for KMI (see The Tax Story Behind Kinder Morgan’s Big Transaction). These two MLPs had depreciated their assets far below their economic value, to the profit up until then of their taxable investors who directly benefited from tax-deductible depreciation not matched by actual economic depreciation in those assets. KMI revalued them, thereby creating a much higher annual depreciation charge on these same assets.

The next logical step will be for KMI to drop down some of these assets into a newly created MLP where the cashflows will not be taxable and the investors in this new MLP can benefit from this higher depreciation. It’s probably too soon for KMI to contemplate such a move, but the tax code creates the possibility of a virtuous cycle whereby assets are first dropped into, and depreciated in, an MLP; subsequently acquired by the C-corp parent with a stepped-up cost basis that resets the depreciation based on current values; and then later dropped again into an MLP. As long as the assets involved have recurruing cashflows, minimal need for maintenance capex and appreciate over time, it’s a legitimate strategy.

The MLP/GP structure contains myriad possibilities. Note also that in November the U.S. was a net exporter of natural gas. Existing in support of an industry that is taking America towards Energy Independence, we think adverse changes to the tax code are highly unlikely and that MLPs have a rich future.

We are invested in ENLC (GP of ENLK), ETE, KMI, WGP (GP of WES), and WMB