The Fed’s Hobson’s Choice

The Fed has a problem with long-term yields. They are remaining stubbornly low, in willful defiance of steadily increasing short term rates. Slowing the economy so as to raise unemployment will be hard unless bond yields move high enough to impede some capital investment and debt issuance. There were signs of this in the spring when rising mortgage yields caused housing to weaken. But ten year notes soon fell back below 3%.

Today’s real yield (defined as the ten year notes minus one year trailing CPI) is –6%. Since the inflation peak of the early 1980s, slowing the economy and increasing unemployment has almost always required positive real rates. We’re not close.

Friday’s payroll report was surprisingly strong. Everybody who wants a job has one. The FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections warns that the Fed funds rate will reach 3.8% by the end of next year. Bond investors are unfazed by this – eurodollar futures are priced for a more sanguine 3.25%, and were even more relaxed prior to Friday’s strong data. But in either scenario, the yield curve will remain inverted.

The Fed’s goal is to drive up unemployment. Their public comments rely heavily on euphemisms because it’s a heartless goal. Inflation is the scourge that harms all, so some of you will be sacrificed (ie lose your jobs) for the greater good. It’s monetary orthodoxy traditionally supported by Republicans, but there is much that could go wrong.

Given employment’s apparent resilience in response to the FOMC’s early moves, it’s possible that short term rates will need to move higher than 3.8%. Ten year treasury yields may need to reach 4% in order to add a few million unemployed, which would presumably require the Fed funds rate to reach at least 5%.

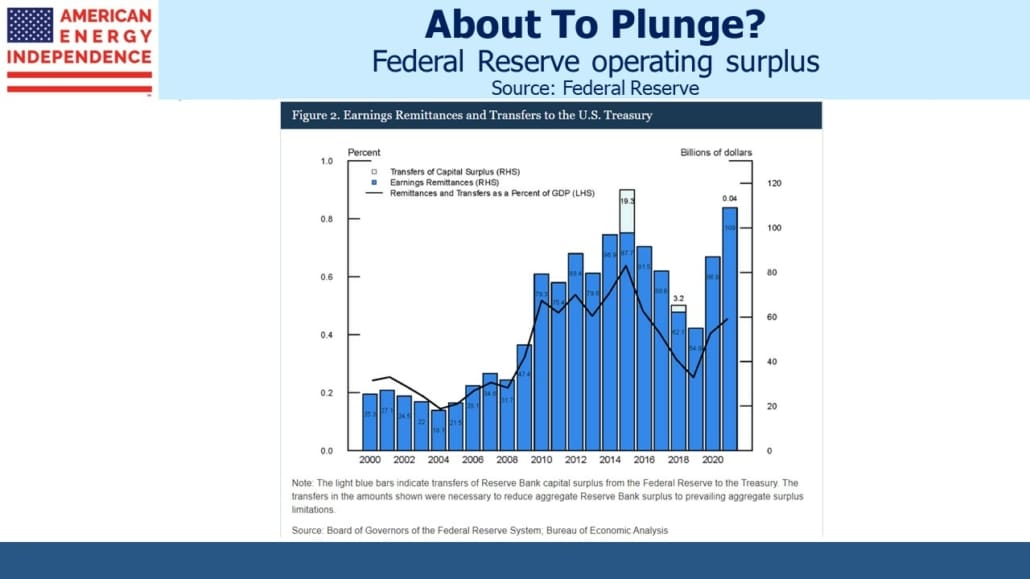

Fed chair Jay Powell will refer to the resulting budgetary problem as merely optical, but Congress may deem it more tangible. The Fed’s $8TN balance sheet has been the world’s biggest positive carry trade, allowing them to remit a $109BN operating surplus to the Treasury last year. By paying close to zero on bank reserves, most of the coupon income from the Fed’s holdings of treasuries and Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS) funded their surplus. The Federal government’s need to fund its budget deficit was lower by this amount.

Last year the Fed’s balance sheet averaged $8.06TN. They reported $126BN in interest income, so earned around 1.5% on their holdings. Maturing short term securities this year may have pushed up the average yield on the remaining portfolio slightly, but with Fed funds at 2.25-2.5% it’s likely they’re now enduring negative carry. The operating surplus will disappear, and on present trends become a deficit by next year.

The Fed shows no inclination to sell anything. Auctioning off treasuries would be tricky because they’d have to co-ordinate with the Treasury’s own auction schedule. But selling MBS would cause the rise in bond yields they need while also reducing their negative carry. However, sales would probably result in realized losses on bonds bought at higher prices. In any event, passive balance sheet reduction is their choice, which means the 2023 operating deficit will be the first one to draw Congressional attention.

Quantitative Easing (QE) followed by its proper inverse, Quantitative Tightening (QT) with selling, means buy high and sell low. Not selling simply swaps realized losses for protracted negative carry. The Fed has implemented it on a scale likely to discredit the strategy as the bill comes due. They only implement QE during a recession, when bond prices are high/yields low.

Restraining the economic rebound QE helped cause will create an operating deficit.

The difficulty in pushing up bond yields, which creates a need for even higher short-term rates, looks like a slowly developing PR disaster for the Fed. But there’s an alternative, plausible outcome. They could point to still modest long term inflation expectations in both the market for Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPs) and the University of Michigan surveys. They could sidestep the struggle to push up bond yields and slow the economy. They could “declare victory and get out”, as Senator George Aiken suggested in 1966 when discussing Vietnam. The Fed could at any time look beyond the latest CPI release and declare inflation to be on a steady path lower – which based on market indicators and surveys, it is. Under such circumstances, the politics of requiring taxpayers to fund their operating deficit would be theoretical.

These two radically different paths imply substantially different rate outcomes. It’s why bonds are so volatile nowadays. Of the two, we lean towards the latter, which avoids a recession and will allow inflation to persist at 3% or higher rather than 2%. But the FOMC’s hawkish posture shows that’s not in their current thinking. Bonds still don’t offer an investment return, but at least there are some fascinating trading opportunities.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment:

Please see important Legal Disclosures.