The Dow’s Odd Construction

Last week’s ejection of Exxon Mobil (XOM) from the Dow Jones Industrial Average looks like another indication of the declining relevance of energy stocks. XOM had been in the Dow since 1928, and until 2013 was the most valuable publicly listed company. Its market cap peaked with oil prices in 2014 at $446BN, and is now around $171BN.

Pfizer (PFE) and Raytheon Technologies (RTX) were also dropped along with XOM, and these three were replaced by Salesforce (CRM), Amgen (AMGN) and Honeywell (HON).

Being dropped from an index is never good. For the much maligned energy sector, it’s tempting to regard this as the bell ringing at the market bottom – the sign that sentiment is so irretrievably poor that the only way from here is up. But the list of such past signals is already long.

The quirky construction of the Dow is the cause of these changes. The Dow may be “venerable”, and still the most widely followed index, but nobody would create anything quite like it today.

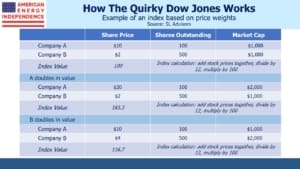

This is because it’s a price-weighted index, rather than market-cap weighted like most indices. This means that the price of a stock determines its importance in moving the Dow. Apple (AAPL) is the highest weighted stock in the Dow by virtue of its price. Because of its impending 4:1 split, its weighting is about to drop by around three quarters – for market cap weighted indices such as the S&P500, a stock split has no impact on the weights of the components.

If Berkshire A (BRK-A) was in the Dow, at $326K per share it would dominate the index.

Perhaps when Charles Dow and Edward Jones first published their eponymous average in 1896, calculating the average daily price of twelve stocks without a calculator was already enough work for two financial reporters. But their simple approach remains with us today.

The tables below illustrate the shortcomings. Perhaps the biggest is that a price-weighted index doesn’t reflect market cap weighted moves in its components. This makes it less representative. From next week moves in AAPL’s value will have much less impact on the index. An investor wishing to track the Dow Jones has to sell most of her AAPL’s shares, even though it’s still in the index. Tracking the Dow is more difficult and costly because it requires frequent rebalancing. That’s why there’s far more money invested in products linked to the S&P500, and they have much lower tracking error. Market-cap weighted indices by definition reflect the experience of all the money invested in their components, and are more easily tracked by portfolios invested in them.

One result is that although the recent rebalancing reflects the biases of the committee that oversees the Dow Jones, the smaller size of Dow Jones-linked funds limited the rebalancing trades by investors tracking the index.

Energy investors can console themselves that XOM’s ignominious ejection is due to AAPL’s meteoric rise and subsequent split. Several big companies have had a sporadic relationship with the Dow. General Electric (GE) has been spurned three times, most recently in 2018. Since then, GE has lost almost half its value. Given valuations, energy investors are likely to do much better.