The Coming Squeeze On Bank Deposit Rates

An Op-Ed in the Washington Post last week suggested that unrealized losses on fixed income investments are likely much higher than the $640BN on held to maturity MBS. It was written by Sebastian Mallaby, who wrote about hedge funds in More Money Than God and has published several other finance books.

Mallaby relies on two recent academic papers which add interest rate exposure on loans to the MBS unrealized losses. Not much data is publicly available on duration risk in bank loan portfolios. Based on the reasonable assumption that loans have an average duration of 3.9 years, the academic papers Mallaby cites estimate US banking system mark-to-market losses of $1.7TN-$2TN, against a capital base of $2.2TN.

These staggeringly big numbers are theoretical and unrealized. Banks are not going to recognize losses anything like that. That’s not to say this isn’t going to be a problem.

It’s worth remembering how we got here. Since Quantitative Easing (QE) was first unleashed in the 2008 Great Financial Crisis (GFC), the Fed has generally found it easier to grow its balance sheet than shrink it. Their huge bond portfolio has depressed government bond yields, which are the benchmark from which all other fixed income securities are priced. The MBS and loans on bank balance sheets mostly originated within the last few years. From mid 2019 until early last year, the ten year yield was below 2%.

Bankrate.com calculates the average rate paid on savings accounts is 0.23%. The Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis calculates 0.35%. Depositors are normally a lethargic bunch but have been galvanized into action by Silicon Valley. Flight from shaky institutions is the current fear, most vividly represented in First Republic’s collapsing stock price. But this problem will likely be solved with a system-wide guarantee on all deposits, not just those under the FDIC $250K threshold. That is de facto government policy today having found Silicon Valley Bank to be systemically important. As the “too big to fail” tent gets bigger, the moniker no bank will want is “small enough to fail”. This is why Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen announced more support for small regional banks.

QE didn’t just help cause a housing bubble, it’s also weakened the banking system. Applied on a sustained basis, QE left them with little choice but to buy bonds and make loans at rates that only prevailed because of the Fed’s enormous portfolio.

Today’s inverted yield curve shows that the problem still exists. Ten year treasury yields are 1% below the Fed Funds rate.

That makes this week’s Fed announcement more important than most, because it’ll reveal how well they understand the banking system’s sensitivity to the funding costs of their vast portfolios of bonds and fixed rate loans that are theoretically underwater. If they regard the depositor run as localized and temporary it’ll mean higher rates to quell inflation remains their primary objective. This will put further pressure on net interest margins.

Held To Maturity (HTM) accounting has once again come in for criticism. The CFA Institute (I sit on the board of the Naples, FL chapter) thinks “hide to maturity” accounting should be abolished because it obscures information investors need. This was considered after the GFC but rejected in 2010 as adding unnecessary volatility to bank financial statements. The information is there if investors choose to look. The problem is that depositors rarely feel the need to consider creditworthiness.

Depositor inertia is what’s under threat. Last year Charles Schwab changed their sweep feature on brokerage accounts to make Charles Schwab Bank the default choice for cash rather than money market funds. Banks routinely pay paltry deposit rates, and this quiet change boosted Schwab’s profitability. We duly adjusted client accounts to hold treasury securities.

This is the real threat facing the banking business model, not depositor runs which are solved relatively easily with a blanket guarantee.

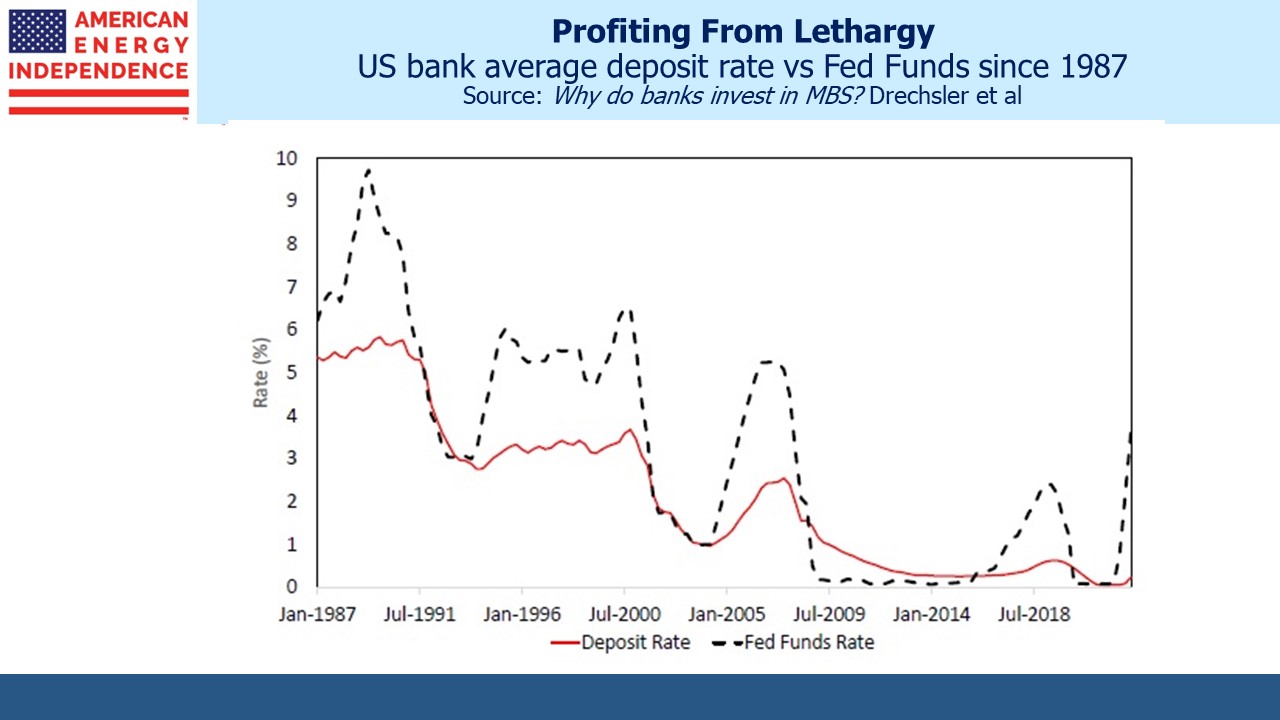

Three academics recently asked Why do banks invest in MBS? in a paper published earlier this month. They include a chart showing how inadequately deposit rates rise during tightening cycles. This captures the banking system’s vulnerability. Deposit rates lag because of inertia among savers. There’s nothing like a banking crisis to make you pay attention to where your money is. Depositors are likely to become more sensitive to savings rates.

Notwithstanding turbulent markets, the case for higher commodity prices remains intact. Goldman’s Jeff Currie believes the commodities supercycle will take oil prices higher by June. Hedge fund manager Pierre Andurand expects oil to reach $140 by year’s end. Citadel’s head of commodities Sebastian Barrack doesn’t expect any long-lasting pressure on commodities.

Inflation risks haven’t meaningfully fallen, but the Fed’s flexibility to confront them has to be balanced with the poor interest rate decisions made across much of the US banking system.

We have three funds that seek to profit from this environment: