The Case For Real Assets

I began investing in midstream energy infrastructure almost two decades ago. When SL Advisors was founded in 2009 it was one of our core strategies. Over the years it’s become our principal focus. Infrastructure possesses enduring qualities for the long-term investor, and energy is just one segment of what’s often referred to as real assets.

Although we focus on energy infrastructure, real assets are much broader than that. They can be structured as REITs. They can be involved in transportation, mining, aerospace and defense. They can be involved in water management and distribution, logistics and the petrochemical industry. Utilities operate infrastructure dedicated to power generation, storage and distribution.

Key attributes of infrastructure include long-lived assets that: provide inflation protection; possess barriers to entry either for regulatory reasons or because of synergies/economies of scale with other assets; generate attractive yields with visible long-term cash flow; and have a low correlation with the equity market.

Maintaining the purchasing power of savings is the goal of all long-term investors other than the foreign central banks and other institutions who hold trillions in US government bonds. Real assets that can raise prices either on commercial terms or because their regulatory framework ensures a minimum return on invested capital can be an effective way to achieve that goal. Oil and gas pipelines often operate under a system of tariffs managed by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Utilities typically have their rates approved by a local regulator. Marine ports and airports often have a scarcity value, in that the alternatives available to shippers and airlines are less convenient or more expensive.

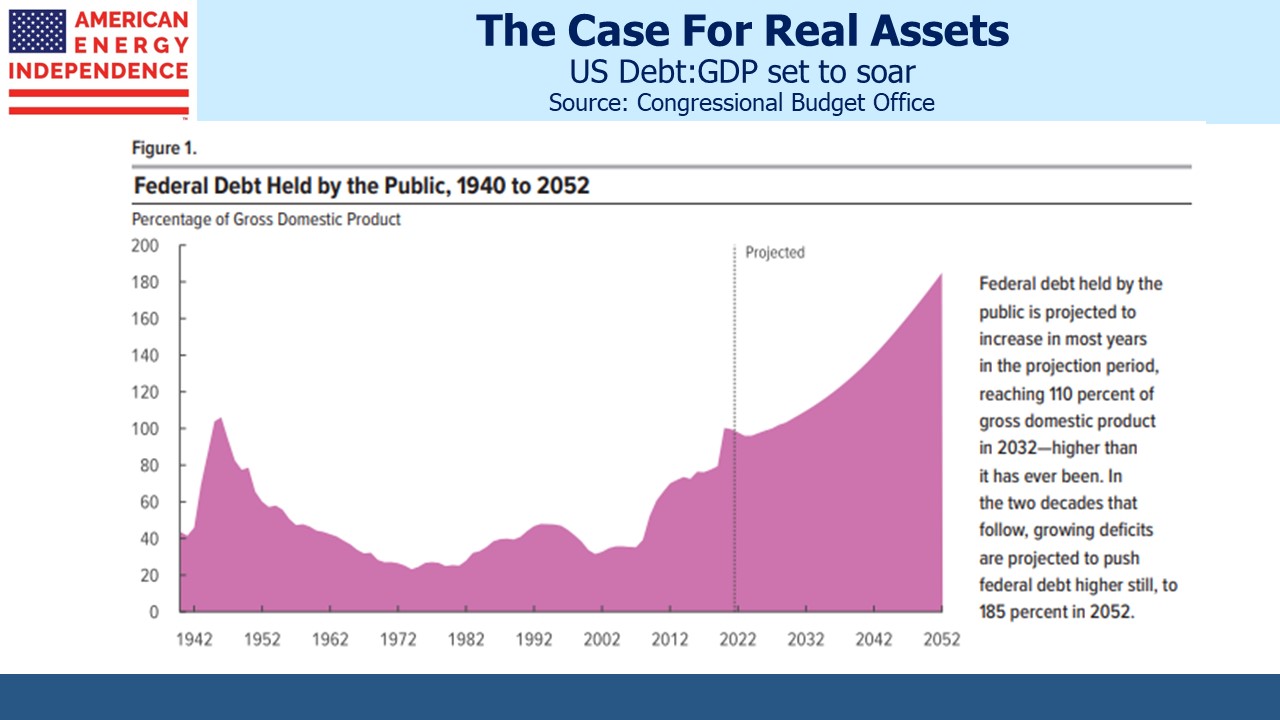

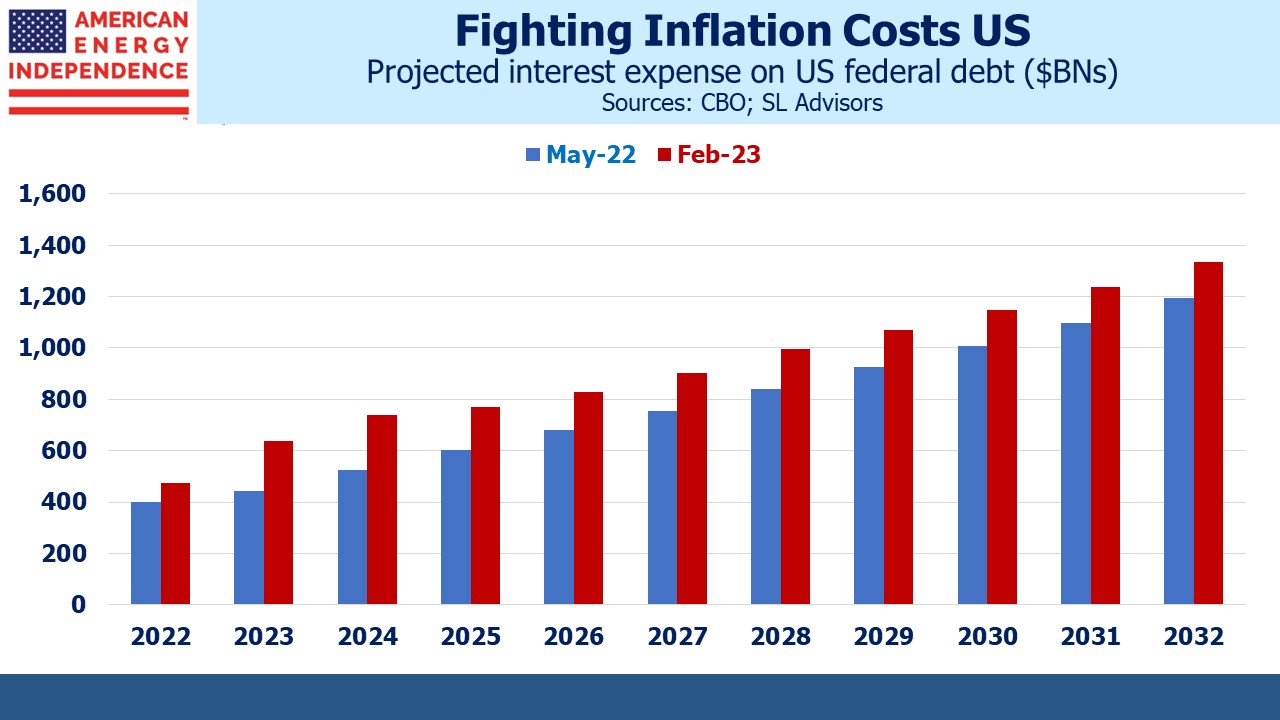

The US fiscal path is well known to be dire and unsustainable. The higher inflation of recent years looks to have dissipated quickly, but the Fed’s sharp increase in short term rates nonetheless raised the cost of financing our debt. Between May 2022 and February 2023, the point at which the Congressional Budget Office forecasts Federal interest expense will exceed $1TN was brought forward by two years, from 2030 to 2028. Higher inflation may turn out to have been transitory this time around, even if Fed chair Jay Powell conceded it wasn’t during its early ascent. But tight monetary policy does hurt our fiscal outlook more than in the past.

This makes it more likely that monetary policy will eventually accommodate our spiraling Debt:GDP by allowing higher inflation and negative real interest rates, increasingly common until the last couple of years. For centuries, monetary debasement has been the refuge of fiscal profligacy.

Infrastructure assets often have barriers to entry. Transco, the natural gas pipeline network owned by Williams Companies that runs through America’s eastern states from Texas to New York is an example. Since its origination in the 1950s, towns and highways have developed that make the construction of a competitor pipeline economically unfeasible. Railroads possess similar features. Where real assets are regulated, it means their stable profits are visible but not excessive, reducing the potential benefits for a competitor.

Established pipelines, railroads and other logistics assets create synergistic connections to other infrastructure, making their replication harder. And scale usually works to the advantage of the incumbent.

Predictable, recurring cashflows allow companies holding real assets to pay a substantial portion of their profits in dividends, which often results in attractive yields. This can be true for REITs, pipelines and many other assets. Just be cautious of utilities with their growing obligation to fund energy transition assets, since this is pressuring their cashflows (see To Lose On The Energy Transition Buy Utilities).

The S&P500 was dominated by the “Magnificent Seven*” last year. JPMorgan calculates that since early 2022 free cash flow growth of the S&P493 (ie excluding the seven) has been flat. Profit margins for the seven high flyers are 2X the other 493.

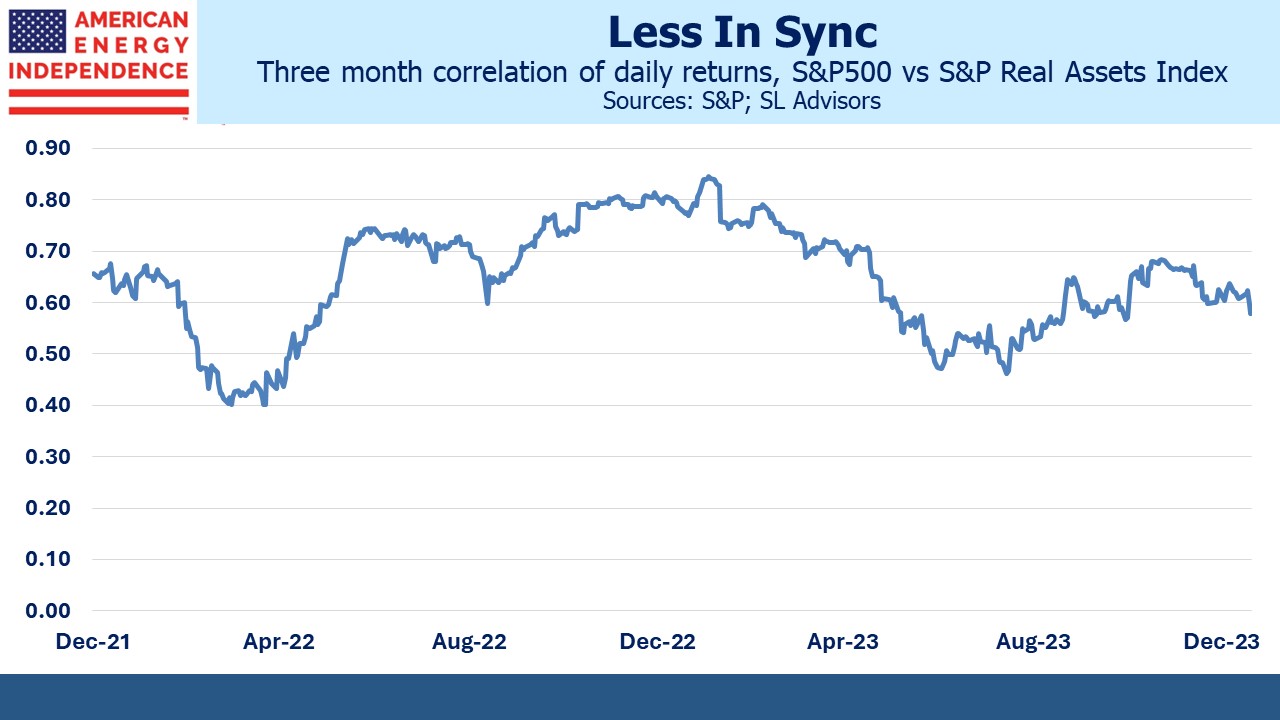

Owning the Magnificent Seven in 2023 was a great call. But they have caused the market to be less correlated with real assets, and when the inevitable reversal happens that low correlation will be welcomed by those who have retained some portfolio diversification.

The dominance of the Seven has led to the market being more “tech-centric”. Because real assets provide good earnings visibility, their valuations tend to be more grounded. They’re less likely to soar on hyped up expectations or plunge on deep pessimism.

Inflation protection, barriers to entry, attractive yields and a low market correlation are all reasons for investors to consider an allocation to real assets.

*Alphabet (GOOG), Amazon (AMZN), Apple (AAPL) Meta Platforms (META), Microsoft (MSFT), Nvidia (NVDA) and Tesla (TSLA)

We have three have funds that seek to profit from this environment: